NOTES ON A SCANDAL: Interview with Kimberli Meyer, Former Director of Long Beach’s University Art Museum

Art institutions often crow about their roles as bastions of progressive thought — places robust enough to tackle tough cultural questions in the gallery. Yet the 2018 firings of several prominent curators and directors exposed the precarity of women who speak out and through their exhibitions and programs, provoke conversations about race, gender, privilege, and power. As we move into 2019, it seems more important than ever to interrogate the dubious narrative of the museum as a safe space, but also to hold out hope that it can be a place of resistance.

Los Angeles–based curator, writer, and architect Kimberli Meyer was fired this fall from her position as the director of Cal State University Long Beach’s University Art Museum (UAM). Her sudden dismissal came in early September, six days before she was to open American MONUMENT, the solo exhibition by lauren woods about the systemic realities of police brutality and the African Americans who lost their lives at the hands of officers. For more than a decade, Meyer was the director of the MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House, and while the Modernist home often exhibited work that made links between art, architecture, and the politics latent in architectural history or urban space, the show at UAM represented her most direct attempt to unflinchingly present issues of race and police violence. It also was an opportunity for Meyer to address issues of structural racism within her own practice as a museum director.

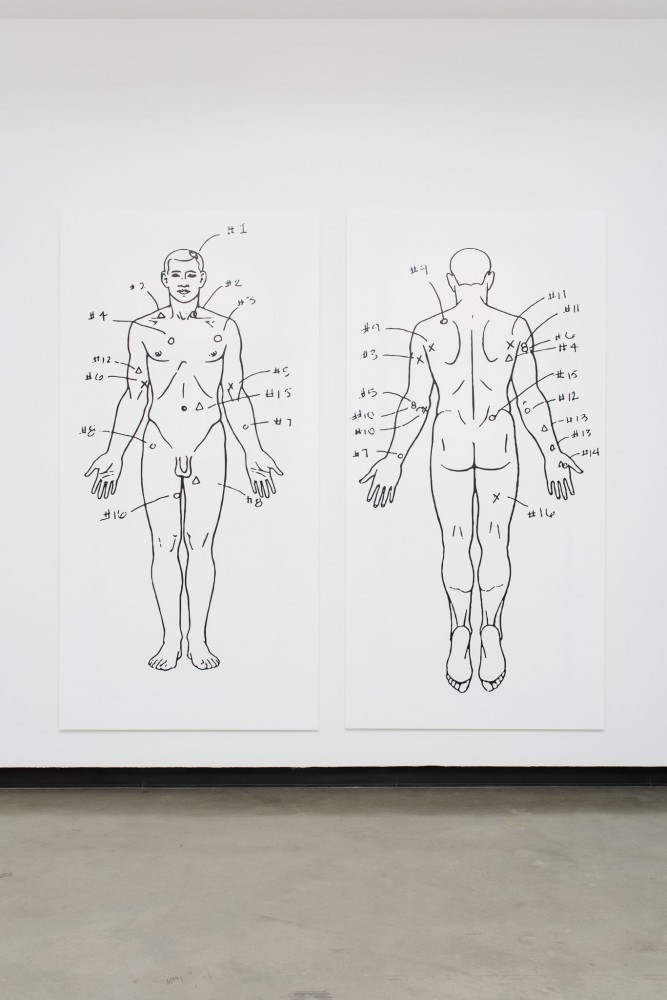

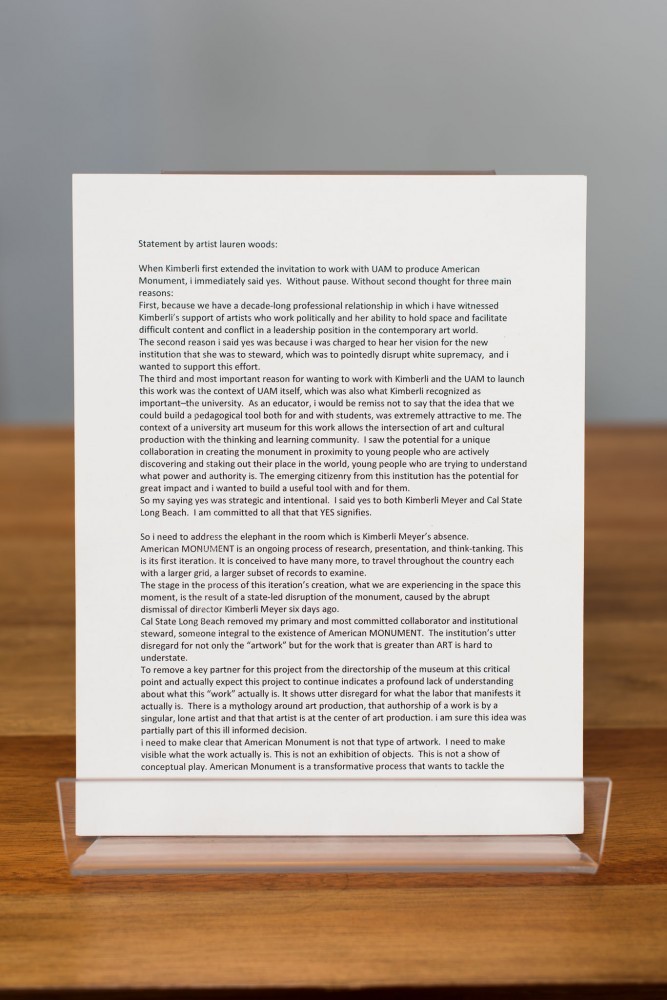

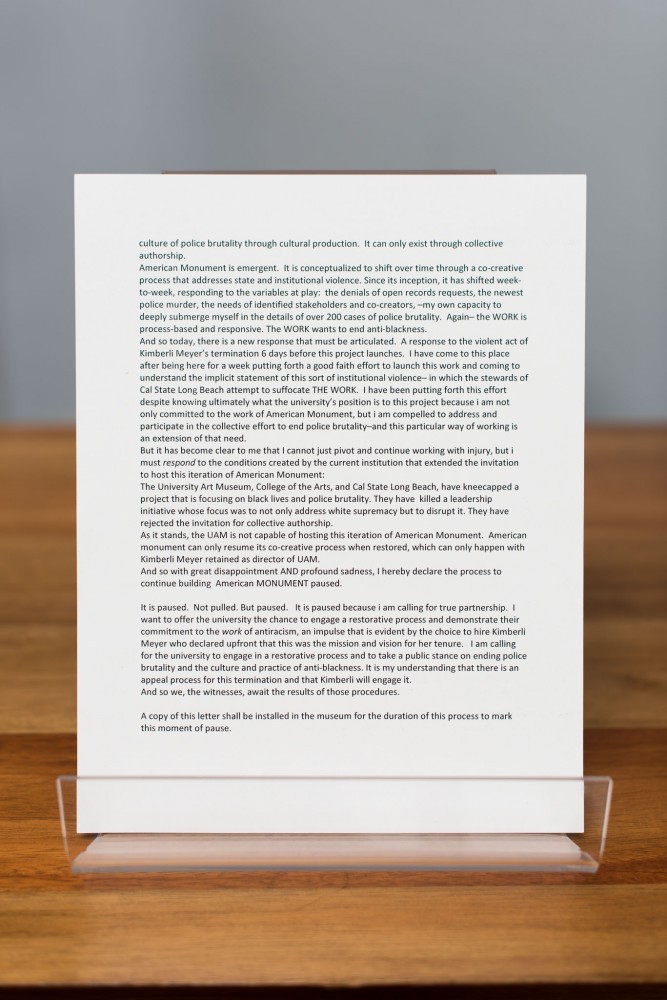

Installed at UAM from September 16th through December 9th, 2018, the core of American MONUMENT is a formal array of turntables. Each one plays a recording of an individual act of police brutality, the sound taken from police reports, court transcripts, witness testimonies, and audio files captured by bystanders. If the decision on the part of the Cal State University Long Beach (CSULB) to remove Meyer from her post was meant to quiet internal discord brewing around American MONUMENT, it had the opposite effect. It set in motion a cascade of actions that amplified attention on the show. At the September 16th opening, woods, in protest of Meyer’s firing, publicly “paused” the exhibition with the words:

"The University Art Museum, College Of The Arts, and Cal State Long Beach, have kneecapped a project that is focusing on Black lives and police brutality. They have killed a leadership initiative whose focus was to not only address White supremacy but to disrupt it. They have rejected the invitation for collective authorship. As it stands, the UAM is not capable of hosting this iteration of American MONUMENT. American MONUMENT can only resume its co-creative process when restored, which can only happen with Kimberli Meyer retained as director of UAM. And so with great disappointment and profound sadness, I hereby declare the process to continue building American MONUMENT paused."

(The full statement is here.)

The silence of that pause was quickly filled with a flood of news stories in the arts press, letters of support, and a confusion of statements from CSULB and the University’s employee union. And Meyer filed an appeal with the University. PIN–UP sat down with her towards the end of her appeals process, to reflect on the American MONUMENT process and her five-year initiative to fight structural racism, which was cut short after two years.

View of the “paused” exhibition American MONUMENT by the artist lauren woods at the University Art Museum, Long Beach. Photo by Jason Meintjes. Courtesy of lauren woods and the UAM.

Tell me about your decision to try to combat structural racism from within an institution.

It started, I would say, in 2013 in a really concrete way. That June, the Supreme Court killed the Defense of Marriage Act. I had been working for women’s rights and gay rights my whole adult life, and then all of the sudden, it was legal for me to marry my girlfriend. That was a big deal for me — a major moment of joy. But it felt so bittersweet, because that same week, they also gutted the Voting Rights Act. So while I gained some rights, a group of other people had their rights taken away. At that point, it was time for me to move on beyond my own interests and really start to think about where I do have power, where I do have privilege, and how to start to direct my activism in that direction. Then three years later, in 2016, I remember reaching a breaking point when I was watching the video of Philando Castile’s death that his girlfriend filmed on Facebook Live. Police brutality against people of color has been going on for such a long time, but people like me who live in a very privileged White world don’t realize it. And now we realize it because technologies, like mobile phones or social media make it visible to us. We see it, and it is unacceptable.

How did this take shape at Cal State Long Beach University Art Museum?

Cal State Long Beach has a really diverse campus in terms of the student body, but not so diverse in terms of the School of the Arts and the administration. There’s a disconnect between who the students are and what their reality is and what (the museum was) paying attention to. I really became interested in this idea of the University as a city, and the shared everyday life and what latent architectures might be there that we could tap. So, that’s when it really all clicked in. I called lauren woods.

It was a little strange to see it the University Art Museum going from an exhibition Robert Irwin drawings to a lauren woods show.

Yeah, yeah. It was a big shift, but that was definitely intentional, too. I told lauren that I wanted her to create something and also that I was introducing a minimum five-year focus on seeing if we could disrupt structural racism somehow from our little outpost.

View of the “paused” exhibition American MONUMENT by the artist lauren woods at the University Art Museum, Long Beach. Photo by Jason Meintjes. Courtesy of lauren woods and the UAM.

How did you begin to sort of frame that disruption (at the museum)?

So it started out at just meetings and discussions. I was trying to keep it broad and I quickly realized I had to keep it away from thinking about ourselves and more about thinking about the general structure. I’d also gave (my staff) reading lists and links to blogs to just get some discussion going. And then a lot of pushback started. The office of Diversity and Equity called me and they were like, “Yeah, you know, you actually can’t force staff to go through diversity training. It has to be voluntary only.” So, to actually ask them to think about these things from their own perspective is bias training. All that stuff is actually off limits. So I got dissuaded from that. They suggested that I started to just focus more on the art, like on the lauren woods project. So I did that.

What was the nature of the pushback?

Some of it was like, “Well that’s not my research interest, and I’m a formalist, and my family assimilated.” Or a lot of it was like, “I don’t even know what this means. What do you mean by that?” Or, "That’s not my job description, that’s not what I’m supposed to do, that’s your thing, that’s not my thing.” At a certain point, I made participation voluntary. I’m going deal with this and there were certain other key staff members who did seem to be interested.

I felt like our reading group started to break down some boundaries for people, and it was interesting to see the staff members who did attend in conversation with the museum studies students. It was so easy for the students to deal with this material. They just got it. They really could talk about this stuff with absolutely no discomfort, and I felt like that helped the staff come along.

What changed as you began working on American MONUMENT with lauren?

I knew what I was trying to do was difficult. In the summer, it started to feel really hard. I got pulled into all kinds of these high level meetings about American MONUMENT, because people were really concerned. I realized that they were concerned because the staff had gone to the union — they were concerned about their own health and safety. They were worried that lauren’s exhibition was going to cause a lot of unwanted attention for the University Art Museum, that the tiki torch white supremacists would show up to protest it, and that people were going to be in danger. Six months ahead of the opening, people wanted to know if I had talked to the police about the show. Right off the bat, a lot of people said: “Like what about the cops? They should be able to have a say.” And my opinion is that, "No, this is not about making a safe space for the cops." American MONUMENT is for people who don’t feel empowered like that. It’s about a space for people to come and think about these things. Poor communities of color have to deal with this bullshit all the time. Eventually, I did go talk to the campus police to let them know it was happening. I made the rounds, talked to counseling, talked to public affairs, etc. But as the summer went on, it just got more and more intense. I realized later, that a lot of the pushback was coming from the staff unions. The University had its own agenda. And a museum is fine if it doesn’t cause trouble, but the moment that it starts to actually push any status quo issue, then it becomes a problem, and everybody wants to manage it.

View of the “paused” exhibition American MONUMENT by the artist lauren woods at the University Art Museum, Long Beach. Photo by Jason Meintjes. Courtesy of lauren woods and the UAM.

How does lauren’s piece, American MONUMENT, aestheticize this fight against structural racism?

lauren had already done a couple of these record players as a stand-alone piece. So that was actually already like a visual, and so I think that part of it wasn't that difficult to do. The formal part of it was actually pretty straightforward. I think it was definitely important for her to, in some ways, avoid spectacle, and I think that it was a big deal to not have imagery. It’s really about language, and the law and culture, and how law is culture. And I think that one of the things that was pretty amazing, is once she identified (examples), we got to work and I assembled a team of students and staff to essentially search these down. She identified 200 or so cases that she felt were compelling. And, so then, we started writing all of these Freedom of Information Act requests to get the records. lauren did these close reads of the documents that we were getting back and started to pick out instances where you could really see how culture is law and vice versa.

With most of these murders, there’s no charge. They just don’t even press charges against the cops. It’s the D.A. that decides whether or not they’re going to press charges, and if they do, somebody has to write a report. lauren noticed that there’s this one guy, Jeffrey Noble, who’s based nearby in Irvine, who, when he writes his reports, refers to the victim as the “victim.” Seems pretty obvious, except that everybody else who writes reports refers to the victim as a “suspect.” That that one shift in language is huge.

Absolutely.

The crazy thing is how the cop story sort of mimics some sort of Hollywood or media narrative of what the bad Black guy supposedly did and said, which doesn’t line up at all with what witnesses say. Not only do they lie, they make up these stories to sound realistic. So, you can see how racist structures get retranslated and reconfirmed.

Former Long Beach Museum of Art Director Kimberli Meyer (left) photographed together with the artist lauren woods during the installation of American Monument. Photograph by Emily Rasmussen. © Press-Telegram

With everything that has happened at Cal State Long Beach and UAM, and the subject matter of American MONUMENT, do see any optimism or hope growing out of this project?

American MONUMENT was always meant to expand and go places. Well, it didn’t work out at Cal State Long Beach and it’s sad, and it’s sad that there was this future potential for the museum to really change. That’s not going to happen. But on the other hand, it raised its profile to the extent that I think that there are places that do want to take on the questions and keep the conversations going. Discussions are happening and hopefully we’ll be able to announce something soon. One of the things that is really great about lauren’s work, is that in the end, it’s not even about an individual cop or a particular shooting. It’s really about the whole structure that allows things to happen — about how the system protects itself and how racism is perpetuated.

lauren forms a pathway to redemption and to hope, because you start to see the kinds of things that you can change — one D.A. uses the word "victim" instead of "suspect." When we generally think that everything is just all fucked up and we can’t do anything about it, that's when despair happens. If you can start to identify exactly where these things are happening and what ramifications they have, then things feel tangible enough to get to work.

View of the “paused” exhibition American MONUMENT by the artist lauren woods at the University Art Museum, Long Beach. Photo by Jason Meintjes. Courtesy of lauren woods and the UAM.

Do you feel that it’s a responsibility for people in arts and culture to take on issues of structural racism?

I think that it’s something that you have to come to. It can’t be forced down anyone’s throat. I think that more than ever now. But at the same time, I would definitely say that just because you think you’re not affected by White supremacy, you are, because you’re benefiting from it. James Baldwin talks about how you can’t just turn a blind eye. Once you understand that things aren’t equal and you understand that there’s a historical reason for that, the moment after that, you can't simply go about your business thinking that everything’s fine, your innocence is over. You’ve lost your innocence. If you aren’t intentional about trying to respond accordingly, then you become a monster. Fake innocence is not something that we should embrace as people who are involved in aesthetics.

Text by Mimi Zeiger.

Images courtesy Kimberli Meyer unless otherwise noted.