ANCIENT ALIENS: What The Acámbaro Hoax Says About Mexican Identity

According to legend, it was a warm summer day in 1944 when, strolling around the hills near the outskirts of Acámbaro, a small village in the central Mexican state of Guanajuato, Waldemar Julsrud almost tripped over a half-buried figurine. In the period 500 BCE to 200 CE, the area had been an important ceremonial and commercial center of ancient Chupícuaro culture, so random discoveries of pre-Columbian vestiges were not uncommon. But what Julsrud, a German hardware merchant and amateur archeologist, unearthed was not the typical shard of worn but colorful ceramic adorned with a geometric pattern: this was a buff clay human figure riding what could only be described as a slightly warped dinosaur.

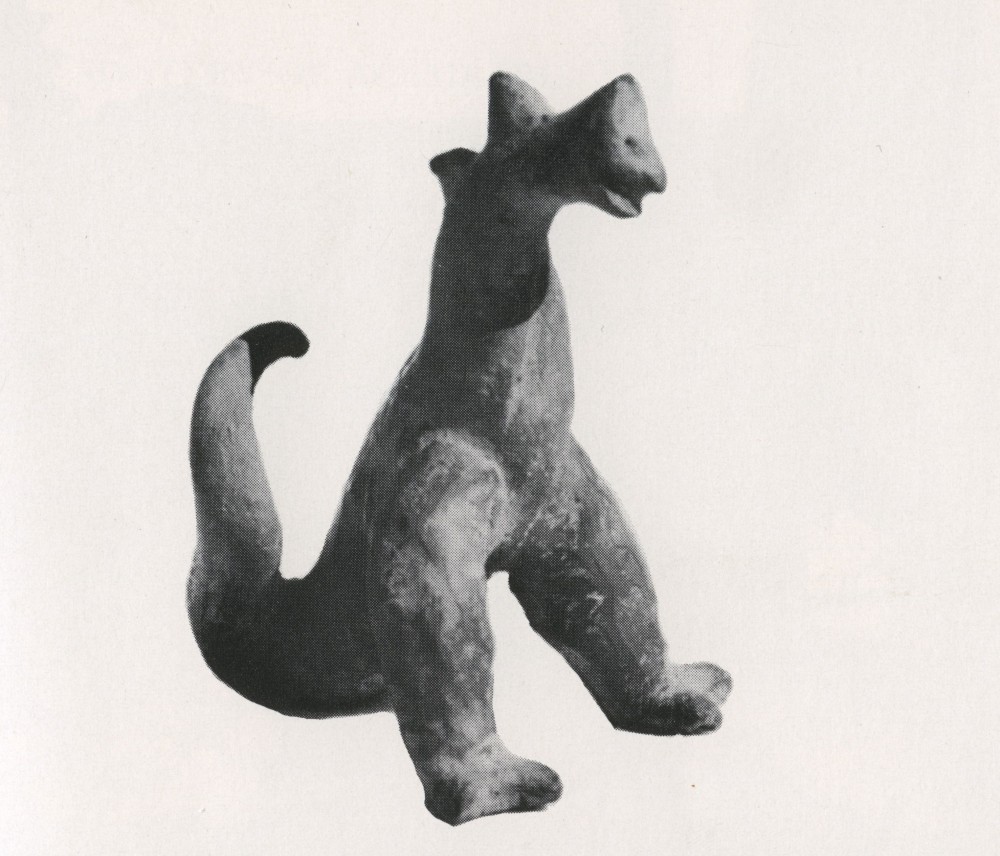

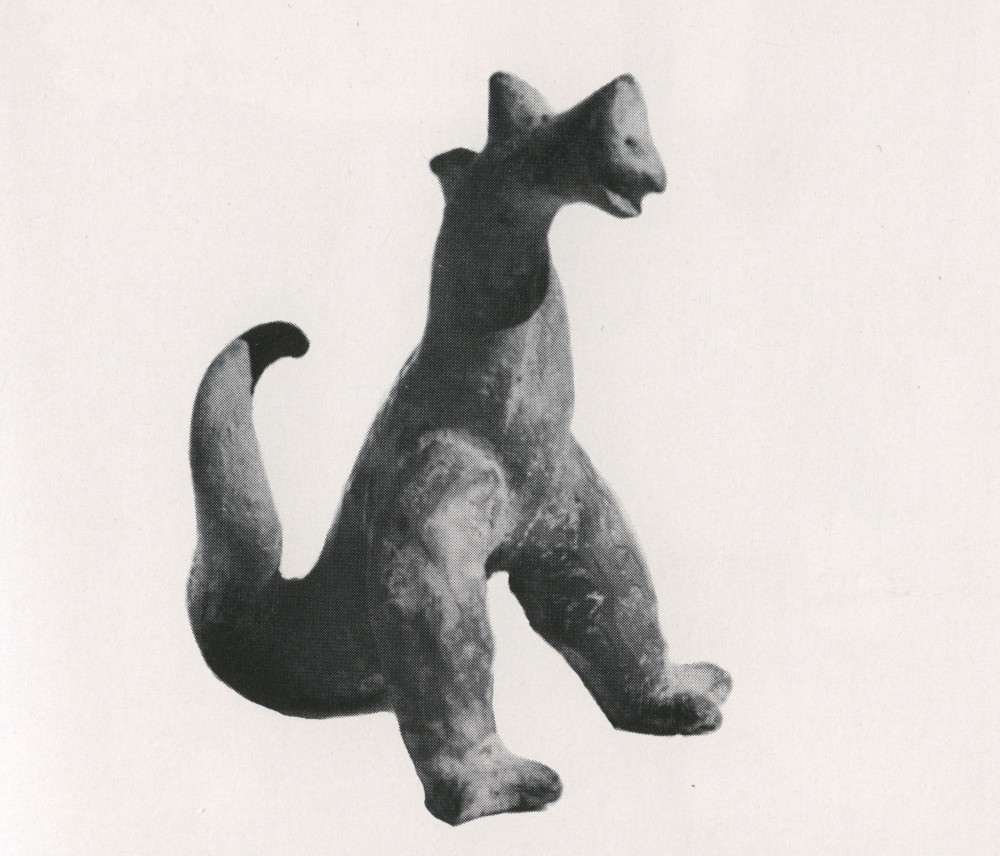

The Acámbaro figures include hybrid fantastical creatures.

His bizarre initial finding led Julsrud to set up an informal digging site, assisted by a local family of farmers. Over 33,000 objects were allegedly recovered, each one more outrageous than the other: a motley crew of prehistoric creatures, idols, utensils, humanoid figures with Egyptian, African, or Indian features, alien lookalikes, complex architectural compositions, dragons, and monsters. The sensational discoveries generated some press coverage, but little interest from formal institutions and archeologists, many of whom found the objects dubious. In 1947, Julsrud decided to self-publish his findings in a pamphlet titled Enigmas del pasado (Enigmas of the Past), and continued to defend and promote his treasures. Four years later, he landed a full-spread story in the Los Angeles Times — “Mexico Finds Give Hint of Lost World: Dinosaur Statues Point to Men Who Lived in Age of Reptiles” — drawing the attention of eccentrics, experts, and skeptics north of the border.

Two opposing sides started to form around the Julsrud clayworks controversy. Anthropologist Charles C. Di Peso, a respected specialist in ancient ceramics, personally traveled to Acámbaro and was the first to officially declare Julsrud’s findings a hoax. The cosmologist and inventor Arthur M. Young, on the other hand, persuaded the Pennsylvania University Museum to organize the first exhibition of the Acámbaro figurines in 1955, which was curated by Linton Satterthwaite under the title Genuine Ancient or Comic Book Art? Julsrud died in 1964, but the debates surrounding the figures continued well into the 1990s, when a group of young-Earth creationists founded the Museo Waldemar Julsrud in Acámbaro, which exhibits the collection and continues to defend its authenticity to this day.

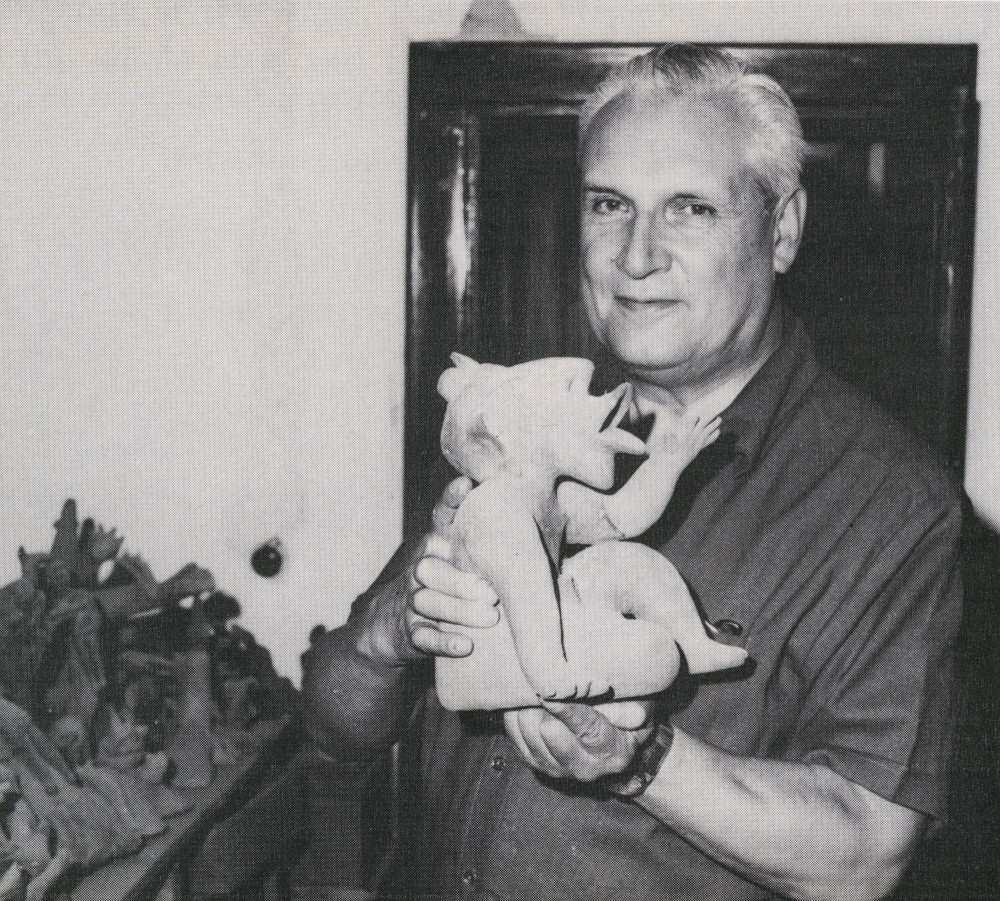

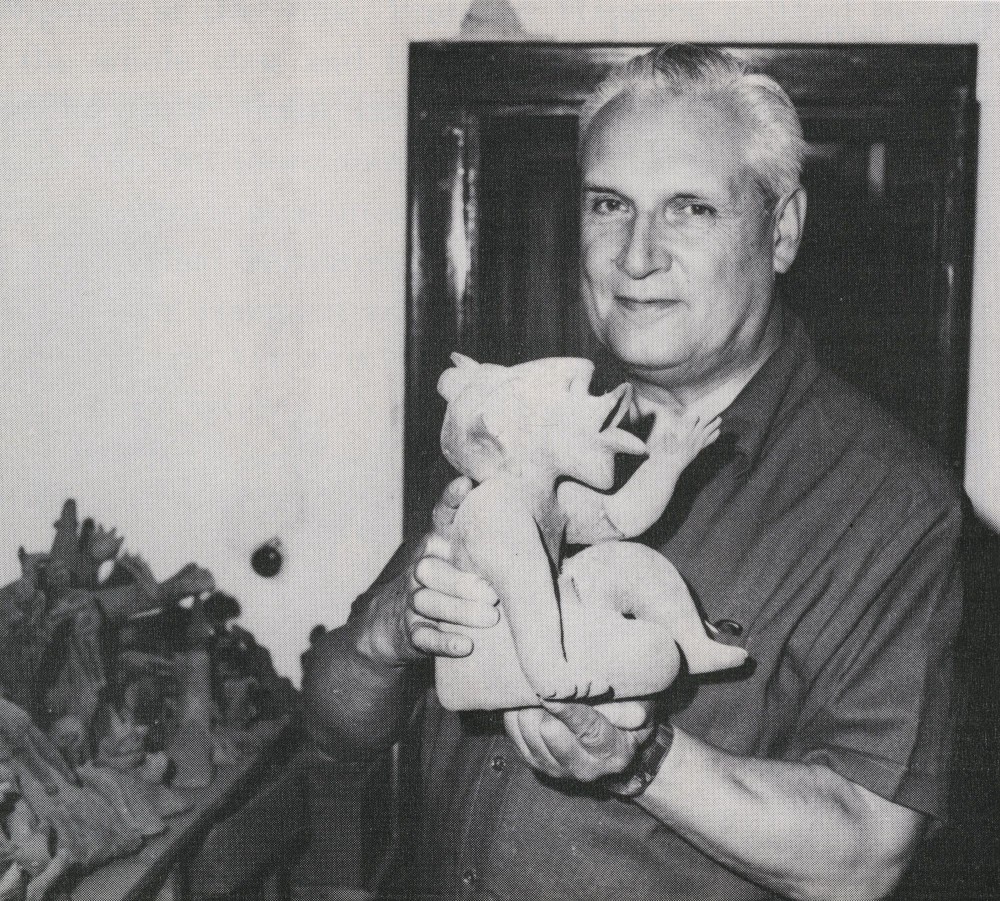

Carlos Julsrud c. 1968 posing with a figure from his father’s collection, allegedly dating back to the Preclassical Mesoamerican period. The site where Julsrud Sr. discovered the figures was the center of ancient Chipícuaro culture.

What is perhaps most interesting about the Acámbaro figures is how they offer an alternative, anomalous construction of Mexico as a “different” place, which rivals Eurocentric pretensions. Around the time when Julsrud was promoting his discoveries, pre-Hispanic art and artifacts were used by the political and cultural apparatuses of the nationalist post-revolutionary Mexican State to bolster the narrative of the country’s unique legacy. During the years of the Good Neighbor Policy between the U.S. and Latin America (1921–36) all the way through the Cold War, a celebration and appreciation of ancient-Mexican culture and traditional crafts had become entrenched in the diplomacy between the U.S. and Mexico. On both sides, the fabrication of an official state image and cultural legacy had many dubious agendas and principles. With its pulpy esotericism and creationist undertones, the Acámbaro story might be an extreme example, but it captures the identitarian anxieties and fantasies of the era, which uncannily echo some of those today.

Text by Mario Ballesteros

All photography courtesy Erle Stanley Gardener