FOUR DAYS IN QUITO: Identity, Development, and the Future of the Ecuadorian Capital

There’s a new wave of practitioners determined to make Ecuador’s capital, Distrito Metropolitano de Quito, a top architectural destination. Leading the way is Tommy Schwarzkopf, the youngest of five Czech-Ecuadorian architects profiled in Arquitectos checos en Ecuador (2016), a book edited by critic Rómulo Moya and published with the support of Schwarzkopf’s construction and real estate company Uribe & Schwarzkopf (U&S). “Ten years ago, there was hardly any interest in Quito from contemporary architects of international renown,” Moya tells me. He says no one was willing to take the risk but, “Tommy’s global vision has changed that.”

With collaborators like Bjarke Ingels, Moshe Safdie, Philippe Starck, and Jean Nouvel, U&S has been rapidly building commercial and residential projects that are already changing the face of the city. Today, for better or worse, Quito is taking a big risk with its global approach on infrastructure and a new initiative for prioritizing public space, while a young generation of climate-conscious, sustainability-driven practices like those of Felipe Escudero, Daniel Moreno Flores, and Diez Muller, gain attention for a different urban vision. With the first subway line set to open in 2020 through the support of Metro Madrid and a recently inaugurated airport in the outskirts of the city (the old airport, closed in 2013, was perilously located within the metropolis), Quito is aiming to be more than just a pit stop on the way to the Galápagos Islands.

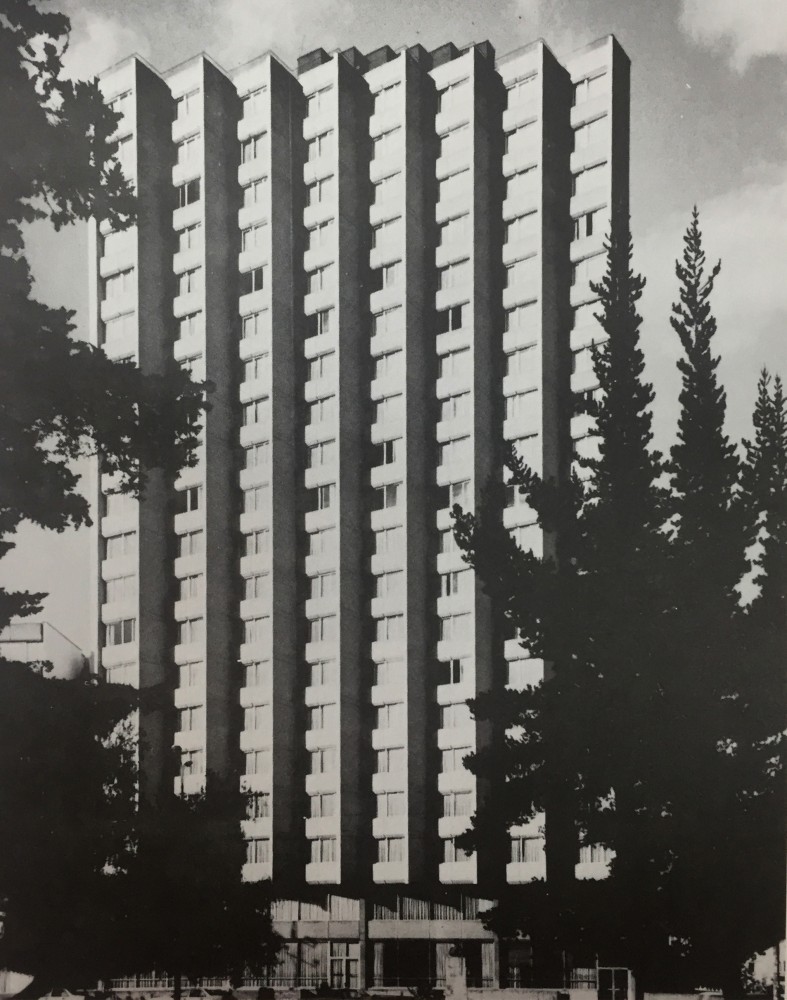

Detail of Edificio Artigas by Milton Barragán. From Milton Barragán Dumet: 60 años de arquitectura © 2019. Photo by Bicubik.

This past August, I accepted an invitation from U&S to see the changing city firsthand. I arrive mid-winter in the Southern Hemisphere to see the pink arupo trees flowering similarly to jacarandas in springtime Mexico City, my hometown. Four days in Quito are barely enough to scratch its surface. The sprawling metropolis is vibrant and complex, with a transformative spirit evident through its eclectic architectural heritage. No single style characterizes the city but, as is common in many Latin American capitals, the imprint of colonization is very much alive in its central plazas, monasteries, and churches, confined mainly within the “hyper-center” on the narrowest stretch of the basin. To the north, high-rise residential towers built within the last ten years have begun to conceal Quito’s Modernist past. To the south, informal commerce, low-income housing, and the evident lack of an urban plan.

Political scientist Camila Lanusse gives me a survey on Quito’s geography and demographics while leading me through Baroque churches which, to my surprise, are intricately Moorish in their interior. Open courtyards with palm tree gardens further confirm the influx from Southern Spain. Most of the “hyper-center,” however, is built in república style from the 19th century, Lanusse tells me, which is evident in the use of adobe walls and roof tiles, mixed with Neo-Colonial elements.

Quito had an architectural awakening in the mid-20th century largely due to the migration of practitioners not only coming from central Europe, but from other South American countries as well. Such is the case of Uruguayan architects Gilberto Gatto Sobral and Guillermo Jones Odriozola, who completed an ambitious urbanization plan between the 1940s–60s that included the Universidad Central where the first architecture school was founded. But the level of opportunity offered to Czech immigrants was considerably generous. Among the architects who came from Prague were Karl Kohn (1894–1979) and Otto Glass (1903–76), who arrived in 1939 and 1940 respectively.

-

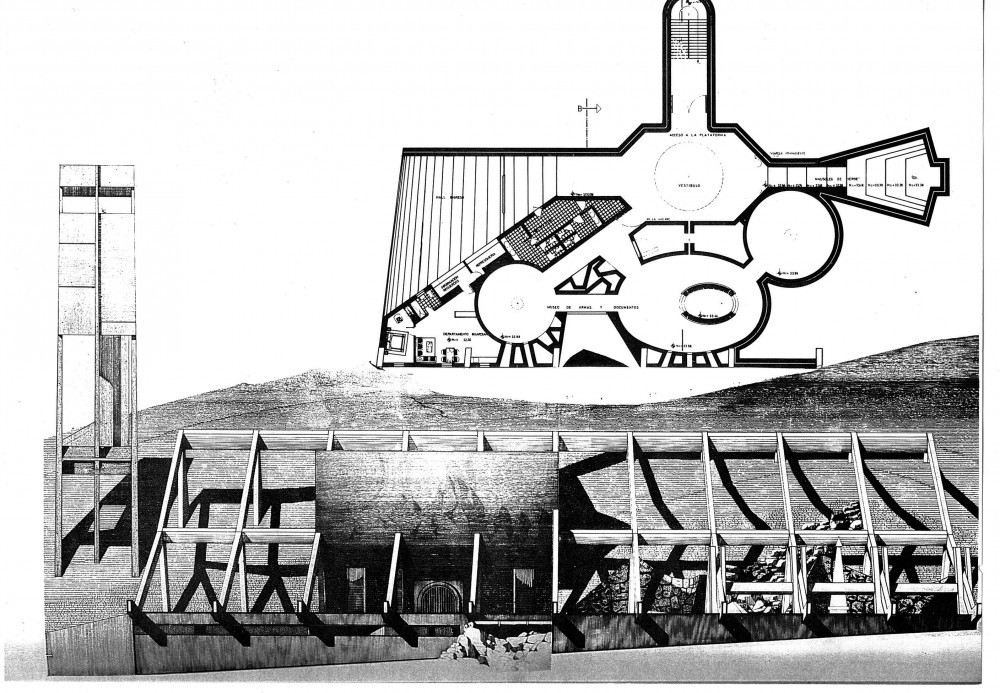

Teatro Politécnico by Oswaldo de la Torre (1965). Photography by Camila Lanusse

-

-

Teatro Politécnico by Oswaldo de la Torre (1965). © Rómulo Moya Peralta. Archivo revista Trama

Kohn was one of the founding professors at the architecture school and served as a consultant for the Ministry of Education. After only four years of practice in the country, he was granted the prestigious Ornato prize, and in 1951, president Galo Plaza was invited to the “opening” of his newly-finished house. Glass is best known for the neighboring house and workshop of Bauhaus-trained Hungarian immigrant Olga Anhalzer-Fisch, completed in 1952. At any one time, Glass could simultaneously have 15 to 20 residential commissions.

After a tour of Kohn’s and Glass’s residences, we stop to glance at Czech architect Ovidio Wappenstein’s (b. 1938) best known trilogy of brutalist buildings on Avenida Patria — the Hilton Colon (1968–78), the Banco Cofiec (1974), and the CFN (Corporación Financiera Nacional, 1980) — the three of which, as claimed by Moya, marked the future of modern architecture in Ecuador. I am most struck by the nearby, but lesser known, Teatro Politécnico (1965). A weighty cantilevered concrete theater by Ecuadorian architect Oswaldo de la Torre (1926–2012), reminiscent of Breuer’s Begrisch Hall by its daring shape. I am puzzled as to why it has not gained as much recognition as the other brutalist buildings designed by architects of European heritage in Quito.

I asked Moya if there was ever a desire to recover the regional identity of Ecuador through architecture — perhaps similar to the way Mexico blended its muralist heritage unto functionalist buildings. “There was always the question of what Ecuadorian architecture was, and the answer almost always referred to Spanish Colonial, forgetting the Pre-Columbian,” he says.

There’s not only concerns about how the city’s architecture has been defined in the past, but also over development determining the metropolis’s future. I chatted about both the complex history of European influence in Latin America and the global influence today in Quito with my guide for the San Diego monastery and cemetery. A local woman who lives a quiet life in the mountains in a wood cabin, she is apprehensive about rumors she has heard of big towers and new developments potentially threatening her home. “Taxi drivers will point out the (U&S) billboards asking ‘Who are they? Do you know what they are doing?’” she tells me. And she doesn’t seem to know the answer either.

COFIEC building by Ovidio Wappenstein (1978).

She’s not the only one with apprehensions. I meet on my last day with architect Fernando Carrión, currently a consultant in the Mayor’s office of Quito working on decentralization issues, cultural heritage, and urbanization, who tells me about the social philosophy of El Buen Vivir (The Good Life), a national plan started in 2007 under president Rafael Correa, which has failed to meet the realities of inequality and diversity in the Ecuadorian territory, an undeniably crucial part of the bigger urban plan. “In ten years, two big infrastructure projects (the new metro and airport) have been completed, both without an urban plan behind,” Carrion tells me, disconcerted by the facts.

Quito’s present is tangled with questions of identity and development, as well as of past and future. As Moya writes, it is crucial to “reconcile the historical moment and our particular needs to achieve an architecture that belongs to us, and that from the spatial, constructive, and ideological, nourishes, fortifies, and drives us.” With the most recent wave of migration flowing from Venezuela’s rapidly deteriorating humanitarian situation in the last two years, the country still faces a great degree of uncertainty on how and where it will continue to grow.

Text by Natalia Torija Nieto.