Decalogue: The Vision behind Visionnaire

-

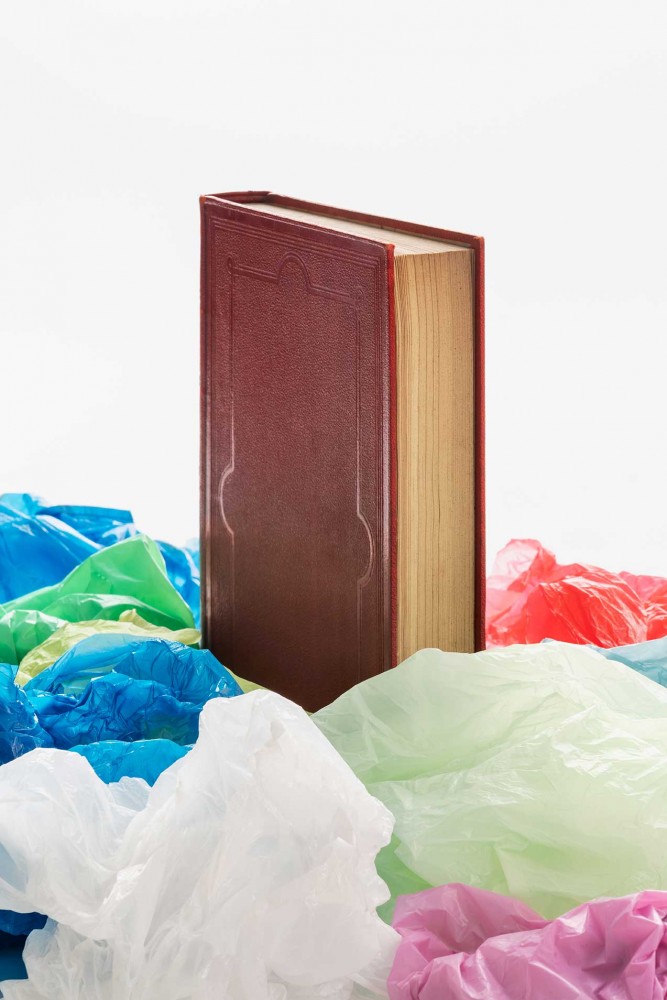

Delfino Sisto Legnani, Luxury (2019). Image courtesy the artist.

-

Marco Piva, Marty console (ADD YEAR); Glass with two bases covered in bronze mirror with embossed surface in relief. Available through Visionnaire. Photograph by Delfino Sisto Legnani.

-

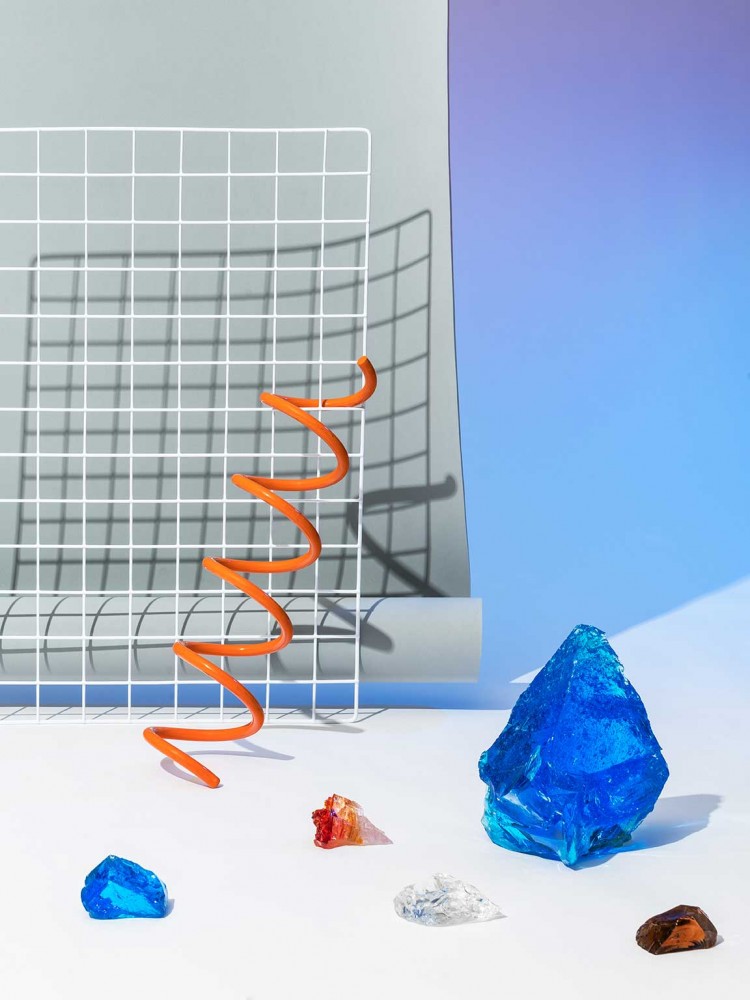

Delfino Sisto Legnani, Vision (2019). Image courtesy the artist.

-

Alessandro La Spada, Kerwan dining table (ADD YEAR); Top in marble, under board in lacquered wood. Available through Visionnaire. Photograph by Delfino Sisto Legnani.

Stepping into the Visionnaire showroom in Milan’s Piazza Cavour, the sight of a bear is the last thing you’d expect. And yet there it is, almost two meters long, with fluffy white fur and a thick gold chain around its neck, looking poised to pounce. Dubbed the Dubhe, the bear is in fact a chaise longue conceived for Visionnaire by Samuele Mazza in a shape that seems at once ergonomic and aerodynamic, like a furry fantasy Formula One race car ready to zoom about the showroom floor and off into the streets of Milan. A humorous, anthropomorphic hybrid bear-lounge is perhaps not what one would associate with Italian luxury furniture, but that is precisely the point: true creativity is the creation of the unexpected, the circumvention and disruption of expected norms and codes.

-

Delfino Sisto Legnani, Culture (2019). Image courtesy the artist.

-

La Conca, Mithra (ADD YEAR); Ceramic vase. Available through Visionnaire. Photograph by Delfino Sisto Legnani.

-

Delfino Sisto Legnani, Nature (2019). Image courtesy the artist.

-

Alessandro La Spada, Carmen padded chair (ADD YEAR); Curved poplar wood, polyurethane padding. Available through Visionnaire. Photograph by Delfino Sisto Legnani.

The Dubhe’s high-velocity look also reminded me of another work of design that disrupts normal relationships to startling effect: Ron Arad’s Rover chair, originally made of two readymade objects found in a London scrapyard — a car seat and a structural tubing frame — it quickly took on icon status and is now found in the most important design collections around the world, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York. What takes the Rover from trash to treasure is the way it transgresses expectations of how individual objects function. Like the Dubhe, the Rover chair makes its meaning by being both radically itself and precisely what it is not. A chair and a chimera, its creative power resides in how it elides typically separate forms and functions, offering an invitation to see things differently.

-

Delfino Sisto Legnani, Design (2019). Image courtesy the artist.

-

Roberto Lazzeroni, Tanya armchair (ADD YEAR); Cold-cured PU foam with internal metal vase, upholstery in leather of fabric. Available through Visionnaire. Photograph by Delfino Sisto Legnani.

-

Delfino Sisto Legnani, Object (2019). Image courtesy the artist.

-

Giuseppe Viganò, Floyd floor lamp (ADD YEAR); Blown glass and satinized steel. Available through Visionnaire. Photograph by Delfino Sisto Legnani.

Arad’s chair takes on additional importance because it speaks directly to Visionnaire’s founding legacy. Created as IPE Cavalli in 1959 as a manufacturer of automobile seats, the company channeled its decades of both artisanal and industrial manufacturing expertise and commitment to quality into the production of high-end furniture. Like the Rover chair, Visionnaire looks to the past and future at once, recognizing that legacy — of design, of style, and perhaps most critically, of craft — is as important to invention as the promise of the new.

-

Delfino Sisto Legnani, Experience (2019). Image courtesy the artist.

-

Mauro Lipparini, Rylan low table (ADD YEAR); Glossy lacquered wood. Available through Visionnaire. Photograph by Delfino Sisto Legnani.

-

Delfino Sisto Legnani, Contamination (2019). Image courtesy the artist.

-

Fabio Bonfà, Backstage sofa (ADD YEAR); Upholstered in leather or fabric, satinized stainless steel frame. Available through Visionnaire. Photograph by Delfino Sisto Legnani.

The serial readymade of the Rover chair and the sensual plushness of the Dubhe also evoke another type of seat inherent to Visionnaire’s legacy: the escapist comfort bubbles that are the seats in modern movie theaters. It is only fitting that Visionnaire’s flagship finds itself in the storied Cinema Cavour, designed in 1962 by Vittoriano Vigano. The theater is classically a space of fantasy, where the moviegoer gives him- or herself up to another reality. That too is the work of great design — we use it to invent our world, and in so doing, reinvent ourselves. Bold and flamboyant, the world of Visionnaire shows us how forging fearless spaces and encouraging experiences that go beyond the mere aesthetic. (Perhaps another reason why Visionnaire regularly supports artist exhibitions in its adjacent gallery space, the Wunderkammer — art as its own form of fearlessness.)

-

Delfino Sisto Legnani, Uniqueness (2019). Image courtesy the artist.

-

Alessandro La Spada, Ekos bench (ADD YEAR); Upholstered bench, base covered in curved polished stainless steel with concave-shaped solid marble side elements. Available through Visionnaire. Photograph by Delfino Sisto Legnani.

-

Delfino Sisto Legnani, Ingenuity (2019). Image courtesy the artist.

-

Samuele Mazza, Klipper dog pouffe (ADD YEAR); Plywood structure and padding in expanded polyurethane. Available through Visionnaire. Photograph by Delfino Sisto Legnani.

The power of design is its ability to make lofty aspiration into tangible material, only to beget further aspiration and imagination. That’s why decorating a dream house is not about realizing one’s fantasy, but rather creating a platform to fantasize even more. Because truly creative work enables and empowers others to give into the urge and exercise their own creativity. In such a world, objects like a curvaceous bear lounge or a roadster-style chair can be endlessly leveraged to create not just new rooms or homes, but new identities, new experiences, new worlds. Because only creative products encourage us to have wider vision — and to be visionaries.

Text by Felix Burrichter. Originally published in Decalogue, a book published on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of IPE Cavalli and the 15th anniversary of Visionnaire Home Philosophy.

Photography by Delfino Sisto Legnani, taken from his exhibition Corrispondenze, currently on view at the Wunderkammer gallery at the Visionnaire showroom, Piazza Cavour, Milan.