ASMARA: Colonial Modernism in North-East Africa

In Asmara, capital of the East African nation of Eritrea, complex questions of cultural identity and political symbolism are interwoven in the fabric of the city’s extraordinary heritage of modern architecture, set pieces from Italy’s short-lived imperial adventure preserved in the dry air of the Eritrean highlands, 7,600 feet above the Red Sea. But Asmara is much more than a collection of architectural fragments. Streets and avenues densely planted with trees connect these works of Rationalist and Novecento architecture, forming a network of urban spaces designed to accommodate political rallies, commerce, and recreation. Asmarans long ago adopted the Italian ritual of the passeggiata, a measured stroll through the city’s piazzas and boulevards in the cool air of early evening. Like their neighbors in Ethiopia, Eritreans describe the geography of their cities in terms that demonstrate the synthesis of indigenous spatial relationships and modern planning practices, from the “piazza” district at the core of each town to the “merkato” which comprises each city’s commercial center. This cohesive urban fabric resulted from several comprehensive urban plans that guided Asmara’s growth from the turn of the century until the end of Italian occupation in 1941.

The Ministry of Education, formerly the Casa del Fascio, on the Harnet Avenue, built between 1928 and 1940 by the architect Bruno Sclafani. © Marco Barbon

Asmara, which for centuries comprised several small villages, grew slowly after the arrival of Italian forces in 1889, during the initial colonization of Eritrea. The next 40 years saw gradual development of the town, including the construction of Art Nouveau, Arts and Crafts, Medieval Revival, and Neoclassical buildings to house the offices, residences, and institutions of the growing colony. The real explosion in Asmara’s growth began in 1935, as Benito Mussolini’s government massed troops in Eritrea in preparation for the invasion of Ethiopia later that year. Over the next six years, Asmara’s European population swelled from 4,000 to over 60,000 (alongside at least 100,000 Tigrinya, Amhara, Arabs, and other Eritreans), and the city’s new residents built hundreds of structures to accommodate schools, markets, cafés, banks, cinemas, factories, gas stations, hotels, post offices, bars, gymnasia, garages, stadia, apartments, and houses. Most new buildings were detailed with streamlined, stucco-clad exteriors, and together they form an ensemble of 1930s modernism as expansive, intact, and significant as those of Miami Beach or Tel Aviv. Asmara’s final stage of planning in the 1930s was simultaneously monumental (appropriate for the capital of Eritrea, one of six provinces in Italian East Africa), prosaic (incorporating the latest in transportation, communication, and sanitation infrastructures), and nefarious (with parks and open spaces designed to separate racially segregated neighborhoods, while keeping the native population close enough to serve as laborers).

The Agip petrol station on Tegadelti Street, built in 1937 by the architects Carlo Marchi and Carlo Montalbetti. © Marco Barbon

The architecture and urbanism of Asmara are no less symbolic now than they were under fascist rule, but what once served as tokens of imperial power have been appropriated as signs of sovereignty and pride: Historian Naigzy Gebremedhin recounts the story of a German architectural firm, which proposed, in 1996, to demolish an unimposing 60-year-old building to make way for the National Bank of Eritrea’s new headquarters. Strong opposition to the project came from an unexpected source, however: elderly Eritreans who had been imprisoned—and in some cases tortured—in the old structure, when it housed an Italian army. This surprising uprising catalyzed a movement to conserve Asmara’s heritage of colonial modernism, and today one and a half square miles of the city center are protected by historical preservation laws enacted in 2001 through the activism of Gebremedhin and the Cultural Assets Rehabilitation Project.

Text by David Rifkind.

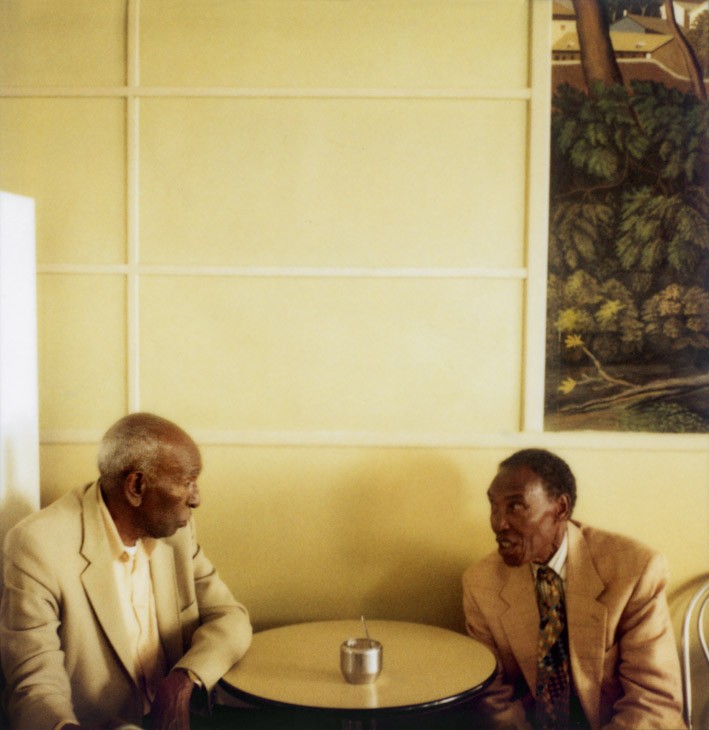

All photography by Marco Barbon.

Taken from PIN–UP 5, Fall Winter 2008/09.