The Art of Daniel Boudinet, or the City at Cibachrome Cruising Speed

Roland Barthes’s last book, which he finished writing shortly before his premature death in March 1980, was La chambre claire. Note sur la photographie (later translated into English as Camera Lucida). An analysis of photography as a medium, it features 24 reproductions of photographs: 23 of them are black and white and discussed in the text, while just one of them is in color, and never mentioned. It features as the frontispiece, and is simply labeled “Daniel Boudinet: Polaroïd, 1979.”

Nénuphars, 1988, Daniel Boudinet, Ministère de la Culture / Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine / Dist. RMN-GP © Donation Daniel Boudinet

For many of us, this enigmatic shot is all we know of the work of French photographer Daniel Boudinet (1945–90) who, like Barthes, died before his time, cut down at the age of 45 by the AIDS epidemic. But now an exhibition put on by the Jeu de Paume at the Château de Tours (Tours, France) provides an opportunity for a new generation to discover his remarkable oeuvre, which focused to a large extent on landscape and the built environment. “Architecture has always fascinated me,” Boudinet once declared. “Obviously it’s something that’s stable, where I don’t want to intervene with anything other than light” — a statement that immediately recalls Le Corbusier’s famous definition of the Reine des Arts as “the masterly, correct and magnificent play of masses brought together in light.” And indeed Boudinet’s polaroid for Barthes perfectly (albeit rather idiosyncratically) illustrates the point: an interior shot, entirely devoid of people, it shows what might be a bedroom — is that the pillow of a single bed at bottom right? —, but what it principally shows is the effect of light, filtered through thin closed curtains that entirely fill the frame, here gathered in darkness, there stretched out in diaphaneity, and starting to rip in the middle, the holes exposing pure white light. Although in color, the photo is actually a monochrome (Barthes expressed his dislike of color photography in La chambre claire, finding it somehow fake), a Whistleresque wash of blue that veers ever so slightly towards the green — discussing photographs of his mother, who he’d recently lost and who dominates the second half of the book, Barthes recalls “the lightness of her eyes … the blue-green of her irises.” Towards the end of La chambre claire, Barthes makes the argument that most people are mistaken when they relate the origin of photography to the *camera *obscura or dark chamber, and that rather they should look instead to the camera lucida, or well-lit chamber (a portable drawing device fitted with a prism that was patented by William Hyde Wollaston in 1806). Boudinet’s chamber (chambre is also of course bedroom in French) is both light and dark at once, metaphorically representing these two origin myths, as well as the hopeful dawning of a new day — or perhaps that terrible moment when the sun begins to rise after the anguish of a sleepless night.

Daniel Boudinet, Tombe Brion, (1982–83). Ministère de la Culture / Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine / Dist. RMN-GP © Donation Daniel Boudinet

Six years prior to his polaroid for Barthes, Boudinet’s first published foray into the built environment was Bagdad sur Seine (1973), a book of poignant black-and-white photographs of Paris that showed the old city transforming into the new: demolitions galore, from a half-torn-down old church to the destruction of Les Halles, via the piles of rubble left behind when the Plateau Beaubourg was cleared to make way for the forthcoming Centre Pompidou; juxtapositions of the decrepit and/or picturesque with the relentless orthogonality of new high-rise apartments and offices; and a whole series where one doesn’t see any architecture at all, just people looking into the sky. What has caught their eye? The 210-meter-high Tour Montparnasse, then going up on the Left Bank. These shots are classically Parisian, mixing both the Surrealist eye of an Atget (one should say proto-Surrealist of course) and the reportage instincts of a Cartier-Bresson or Doisneau. While Atget would never leave him, Boudinet would later eliminate all traces of Doisneau and his ilk, in a rather radical move that also involved the switching of black and white for color.

-

Vue au crépuscule du Pont Alexandre III, Daniel Boudinet, Ministère de la Culture / Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine / Dist. RMN-GP © Donation Daniel Boudinet

-

Phuket, Thaïlande, 1988, Daniel Boudinet, Ministère de la Culture / Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine / Dist. RMN-GP © Donation Daniel Boudinet

“I think it was in reaction to a certain ‘French’ photography, which characterized a particular era, that of Doisneau and Cartier-Bresson, which was very close to photojournalism,” he later said. This photography of the “instant, especially with respect to human action” was “a trail I no longer needed to follow because it had already been blazed, and even overexploited.” It was in his series of nighttime urban shots, which he began taking in 1973 shortly after publication of Bagdad sur Seine, that Boudinet got entirely rid of people and of the anecdotique in favor of that pure play of architecture under light. But rather than the life-giving sunlight of Le Corbusier’s world vision, it’s the sodium and fluorescence of street lamps that bring to these images their particular quality, to the point where, as Boudinet pointed out, “the blue, green, white, or orange colors produced by these lights play such a role that reproduced in black and white these photos lose their true meaning.” Take for example a view shot in Rome in 1975: the composition is very flat, almost entirely without depth; it is dominated by a giant black L filling two thirds of the frame; in the foreground a cobbled roadway is awash with reflected light; but what draws the viewer in is a large section of bare wall, in front of which stands an elaborate old street light whose sodium glow has turned the wall’s surface into the most extraordinary chromatic poem in orange-tinted yellow. It immediately recalls Proust’s famous pan de mur jaune in Vermeer’s View of Delft, “a little patch of yellow wall … so well painted that it was, if one looked at it by itself, like some priceless specimen of Chinese art, a beauty that was sufficient in itself” (Proust, La Prisonnière). Contrast this with a London shot from 1977: ostensibly it’s a very similar subject, the effect of a street lamp on an urban scene, with yellow stonework brought out in all its splendid detail both on the sidewalk and the wall occupying the middle ground. But here, although the same flattening framing has been used, the image is all about space, manifested through the effects of light — both the pattern cast by the street lamp on the ground but also the shadows that indicate a mysterious receding stairway in the background. Or let’s consider another shot from 1975, this time taken in Paris, as can be understood if you peer into its left-hand corner — that seems to be one leg of the Eiffel Tower catching the glare of the orange night-time haze. But what dominates and brings depth is the concrete foreground, lit by a whiter lamp that has turned it green-blue, and is also making the shadows beneath the background vegetation that much more menacing — or enticing depending on your state of mind. For surely there’s also something of Boudinet’s sexuality in here, these being nothing if not cruising shots where the hunt was double — not only for that perfect image, but also perhaps for the boys one feels must be just outside the frame, round the corner, behind the trees, or obscured in the shadows of those tantalizing steps.

-

Sculpture dans un parc, 1977, Daniel Boudinet, Ministère de la Culture / Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine / Dist. RMN-GP © Donation Daniel Boudinet

-

Route et carrefour1977, Daniel Boudinet, Ministère de la Culture / Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine / Dist. RMN-GP © Donation Daniel Boudinet

-

Route et carrefour1977, Daniel Boudinet, Ministère de la Culture / Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine / Dist. RMN-GP © Donation Daniel Boudinet

“Daniel was very handsome back then,” recalls architect and historian Philippe Duboÿ. “Splendid!” Duboÿ came to know Boudinet well after commissioning work from him. “When I was writing about contemporary architects, I never liked architectural photographers, so I would look for professional photographers whose subject wasn’t necessarily architecture. Daniel was the first I chose, by chance, because I met him through his then boyfriend. I got him to photograph buildings by Bernard Paurd and Nicolas Soulier. And when they saw the results they were pretty surprised! (Laughs.) Paurd had done a social-housing complex in Reims, Les Masques, with entrances that looked like masks. Daniel photographed them from a low angle with strong, dark clouds behind — the result was rather carnivalesque but very beautiful. At first, neither Paurd nor Soulier liked the pictures of their work, but later they adored them and even had Daniel take their portraits.” Duboÿ was also behind what is probably Boudinet’s best-known photo series, of Carlo Scarpa’s Brion Tomb and Sanctuary in San Vito d’Altivole, outside Treviso, Italy. “The first time he went to the Tomba Brion it must have been in 1983, a very cold winter. He had a little moped and would go off every morning to wait for dawn — for him the most beautiful light was at dawn and at sunset. And he would stay the whole day in the freezing cold. And he did that every day for a fortnight. We all said to ourselves he was going to produce a fantastic reportage. But at the end of that first trip, all he gave me was one single image, showing part of the tomb with a line of golden mosaic. And he said, ‘For me, that’s the tomb.’ I can’t honestly say I was surprised.”

-

Place du Trocadéro, Paris, juillet 1978, Daniel Boudinet, Ministère de la Culture / Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine / Dist. RMN-GP © Donation Daniel Boudinet

-

Réverbère et éclairage nocturne, 1975, Daniel Boudinet, Ministère de la Culture / Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine / Dist. RMN-GP © Donation Daniel Boudinet

Almost a monochrome, the print, like the patch-of-yellow-wall shot, is framed by an L of sky at the top; but here it is the weak white sky of a winter dawn, tinged ever so slightly with pink; the concrete of the tomb, in chromatic contrast, has turned a deep and rather chilly blue, against which the yellows of the mosaic stand out in startling brightness. And again like the Rome shot, the composition is essentially flat, depth only being hinted at by a patch of middle ground to the right. Reproductions of this photograph, or of any of Boudinet’s nighttime series, can be misleading, not only because the color matching is frequently off but because they distort the scale of the original. Working in a pre-digital age, Boudinet produced objects, not pixels, in this case, Cibachrome prints. A now obsolete technique, Cibachrome is a dye-destruction positive-to-positive photographic process used for the reproduction of transparencies; polyester-based photographic paper is covered with 13 layers of richly colored, highly stable dyes, which are bleached off in processing to achieve the final image. It takes skilled technicians to achieve a good result, and photographers often developed close relationships with their developers, as Boudinet must have done with his. Nothing, therefore, beats seeing the original prints, which Boudinet kept deliberately small (12 x 17.5 centimeters for the Rome shot, for example (4.75 x 6.89 inches)), so that the viewer is forced to peer into them, rather in the way that one squints into the jeweled colors of 16th-century miniatures. Where his black-and-white work was concerned (Boudinet switched between the two throughout his career), he would, like most photographers, print the negatives himself. Despite the absence of color, the results appear highly chromatic in their palette of every imaginable type of gray, as evidenced, for example, by his 1985 shot of a building in Calmaggiore, Italy, by Afra and Tobia Scarpa (another Duboÿ commission) or his atmospheric series of the gardens at Bomarzo, which was published in eponymous book form in 1977.

-

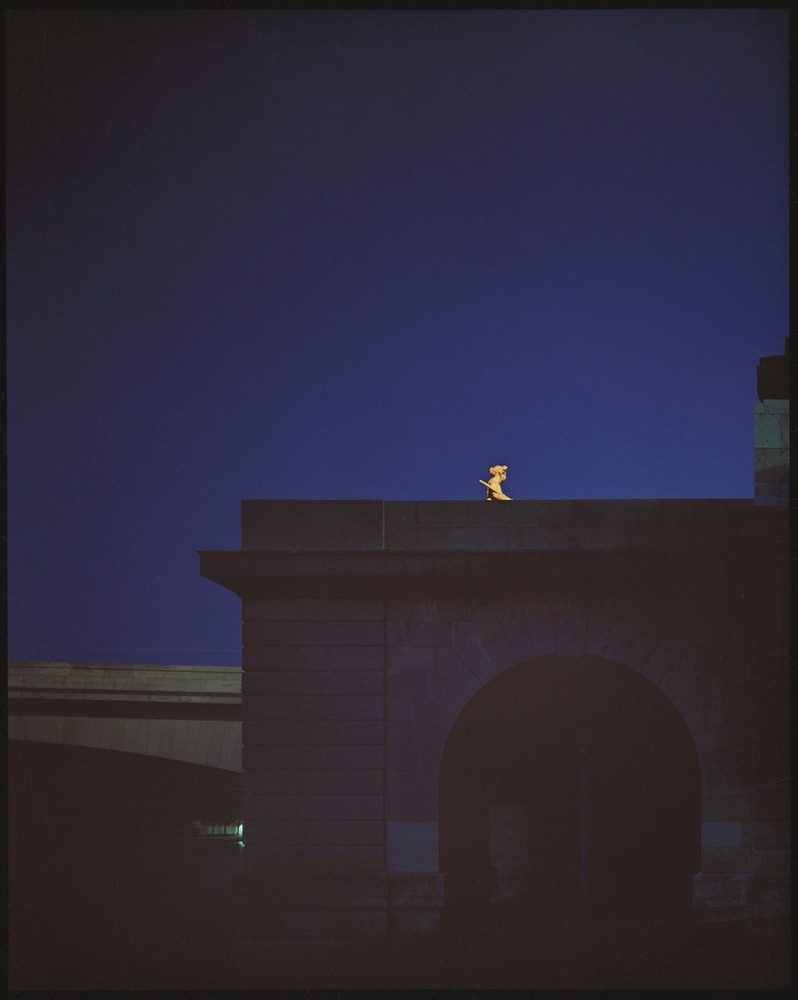

Vue nocturne d’une pile de pont et d’une statue illuminée, 1985, Daniel Boudinet, Ministère de la Culture / Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine / Dist. RMN-GP © Donation Daniel Boudinet

-

Paysage de Camargue, 1987, Daniel Boudinet, Ministère de la Culture / Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine / Dist. RMN-GP © Donation Daniel Boudinet

It is an old truism to say that architecture is an art which incorporates the notion of time: the promenade architecturale so beloved of Le Corbusier requires the visitor to discover a building and its architect’s intentions in both time and space as (s)he moves gradually through it. And the relationship between time and space is something that is very strong in Boudinet’s work. Indeed the notion of cruising — another domain in which time plays an important role — comes back in a statement he made in 1978: “I like to think that the time contained in my photo could be symbolized by a person crossing the rectangle at a normal pace.” For those readers not familiar with the activity, cruising as practiced in outdoor spaces such as parks, cemeteries, dockyards, or back streets generally involves a lot of time spent standing around watching and waiting, interspersed with to-ings and fro-ings, frequently across an open space, where one can be seen, towards the shadows on either side, where things might happen. Boudinet’s city night shots are like stage sets for cruising, just waiting for a figure to walk across them, inviting the viewer to imagine their own ideal subject ambling into the space, or perhaps — yet more voyeuristically — to picture what kind of man Boudinet himself would have hoped to see enter the frame. Time is also bound up in the way Boudinet created his images, days and sometimes weeks of preparation being involved, as we have already seen with his definitive shot of the Tomba Brion. In preparation for an official commission to photograph Paris’s Panthéon, he even spent whole nights in the building. (At the opening of the Jeu de Paume show, Boudinet’s sisters gathered in front of a Panthéon shot which features a mysterious figure bathed in saturated red light. “Who could it be?” they wondered. “Daniel? No, wrong profile. A lover…?”) “Everything was meticulously thought through in advance,” recalls Duboÿ, “— the lighting, the framing, the exposure. Some photographers take thousands of shots in the hope of getting just one good one; Daniel was very sparing in the number he took.” Of his nighttime-cities series, Boudinet said, “Everything is related to my wanderings: first to find the spot I want to photograph, then slowly to discover the ideal viewpoint that will allow me to produce the photograph.” Exposures could last several hours, the ultimate expenditure of time in a long process by which, in order to be able to photograph something, he felt one needed to look at it “to the point of boredom.” This approach comes through with velvet violence in a nocturnal series of what must surely be his own apartment, bathed in a spectral blue light that caresses bookshelves, mantelpieces, windows, and umbrella plants. Gathered under the title Fragments d’un labyrinthe (1979), these oneiric shots seem like a hallucinatory study of self-haunting, a subaqueous poem to insomnia. “Today, what unknown spaces are there? I believe that they are those of total intimacy, those where the photographer can find his personal poetry,” Boudinet once said.

-

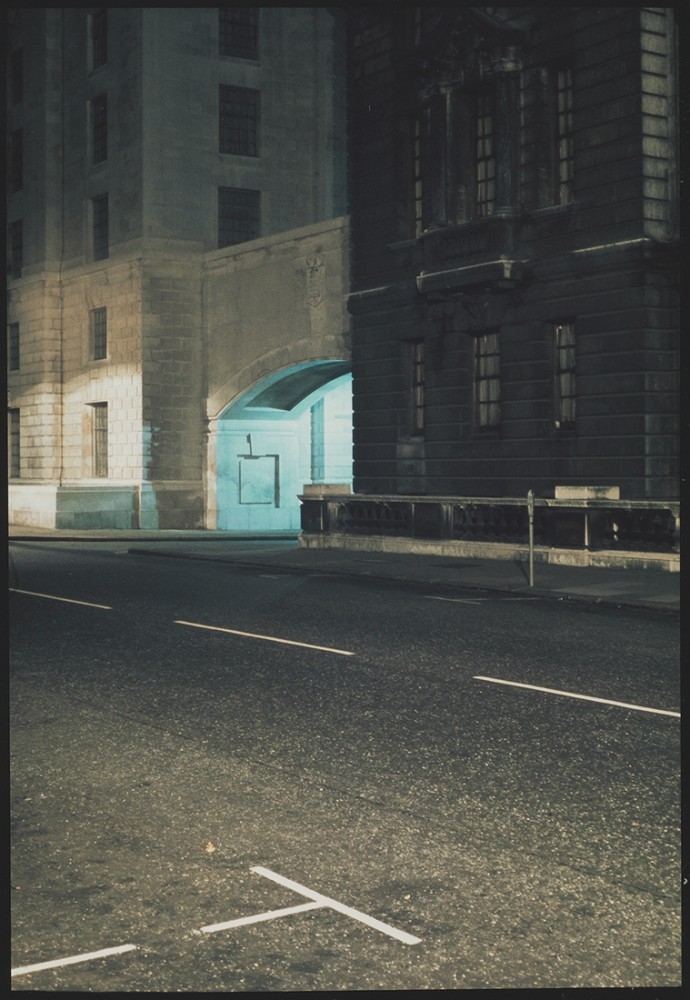

Rue, passage et effet lumineux, 1977, Daniel Boudinet, Ministère de la Culture / Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine / Dist. RMN-GP © Donation Daniel Boudinet

-

Vue d’une étendue d’eau et des herbes alentours, 1987, Daniel Boudinet, Ministère de la Culture / Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine / Dist. RMN-GP © Donation Daniel Boudinet

Boudinet’s friendship with Barthes, who it seems he met around 1970, was an important relationship in his life. He photographed the philosopher on several occasions, and in 1977 asked him to write a commentary on a series of black-and-white rural scenes he’d taken for the review Créatis. Barthes, as a letter in the Jeu de Paume exhibition testifies, was hesitant about accepting since he was at the bedside of his ailing mother, but he agreed to the job “because I love both you and what you do.” Some of the thoughts Barthes jotted down for the Créatis commentary would go on to inform his thinking for La chambre claire, the original draft of which (as another document in the show attests) mentioned Boudinet in a parenthesis on polaroids: “Polaroids? Amusing but disappointing, except when Daniel Boudinet gets involved.” (In the final draft, “Daniel Boudinet” was replaced by “a great photographer.”) One of the hypotheses that Barthes develops in La chambre claire is that photography is synonymous with death: for him it is a medium which, in its attempt to capture and preserve the life of its human subjects, immediately and paradoxically kills them off, making of them instant specters (unlike moving images, which, he says, still have the promise of a future in front of them). Great admirer of Proust that he was (La chambre claire is peppered with Proustian references), Barthes couldn’t help but be horrified at photography’s effect on the act of memory (which is what, in the end, À la recherche is all about), “these photographs of a being in front of which we remember him less well than if we simply settle for thinking of him” (Proust, Le Temps retrouvé). In an essay on Boudinet’s work published the same year that La chambre claire came out, the author and critic Bernard Lamarche-Vadel picked up Barthes’s assimilation of photography with death and ran with it, describing how for him the inherent “rigidity” (a form of rigor mortis) that photography confers on its subjects becomes a virtue in Boudinet’s land- and cityscapes: banishing all traces of the living, refusing all the tricks photographers usually resort to in their vain attempts to bring their shots “alive” (as exemplified by a Doisneau or a Cartier-Bresson), Boudinet, according to Lamarche-Vadel, brought into play a phenomenon of “statuification” through his handling of light, which is used to form “a series of frames … lactescent shrouds whose function is anchoring and immobilization” so as to produce a sort of monument (Barthes had argued that photography must have had something to do with “the ‘crisis of death’ that began in the second half of the 19th century,” a crisis in which death becomes banal and flat, like photographs themselves, in opposition to the ritual act of memory that is a funerary monument). This effect of petrifying monumentalization is very evident in, say, Boudinet’s 1975 shot in Rome, the one with the patch of yellow wall discussed earlier. And in Proust, moreover, the patch of yellow wall in Vermeer’s painting (a sort of monument itself) turns out to be directly linked to death: the writer Bergotte (whose ailments and illness-induced agoraphobia were clearly autobiographical on Proust’s part) makes the supreme effort to leave the sanctuary of his bedroom to venerate the pan de mur jaune in Vermeer’s picture, which he has read about in an essay by an art critic. And it’s there, in the gallery, that he has one final attack, and dies in public, in front of the picture.

-

Rue et impasse1977, Daniel Boudinet, Ministère de la Culture / Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine / Dist. RMN-GP © Donation Daniel Boudinet

-

Crique, Majorque Espagne, 1987, Daniel Boudinet, Ministère de la Culture / Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine / Dist. RMN-GP © Donation Daniel Boudinet

“He was dead. Dead forever? Who can say? Certainly, experiments in spiritualism offer us no more proof than the dogmas of religion that the soul survives death. All that we can say is that everything is arranged in this life as though we entered it carrying a burden of obligations contracted in a former life; there is no reason inherent in the conditions of life on this earth that can make us consider ourselves obliged to do good, to be kind and thoughtful, even to be polite, nor for an atheist artist to consider himself obliged to begin over again a score of times a piece of work the admiration aroused by which will matter little to his worm-eaten body, like the patch of yellow wall painted with so much skill and refinement by an artist destined to be forever unknown and barely identified under the name Vermeer. All these obligations, which have no sanction in our present life, seem to belong to a different world, a world based on kindness, scrupulousness, self-sacrifice, a world entirely different from this one and which we leave in order to be born on this earth, before perhaps returning there to live once again beneath the sway of those unknown laws which we obeyed because we bore their precepts in our hearts, not knowing whose hand had traced them there — those laws to which every profound work of the intellect brings us nearer and which are invisible only — if then! — to fools. So that the idea that Bergotte was not dead forever is by no means improbable.

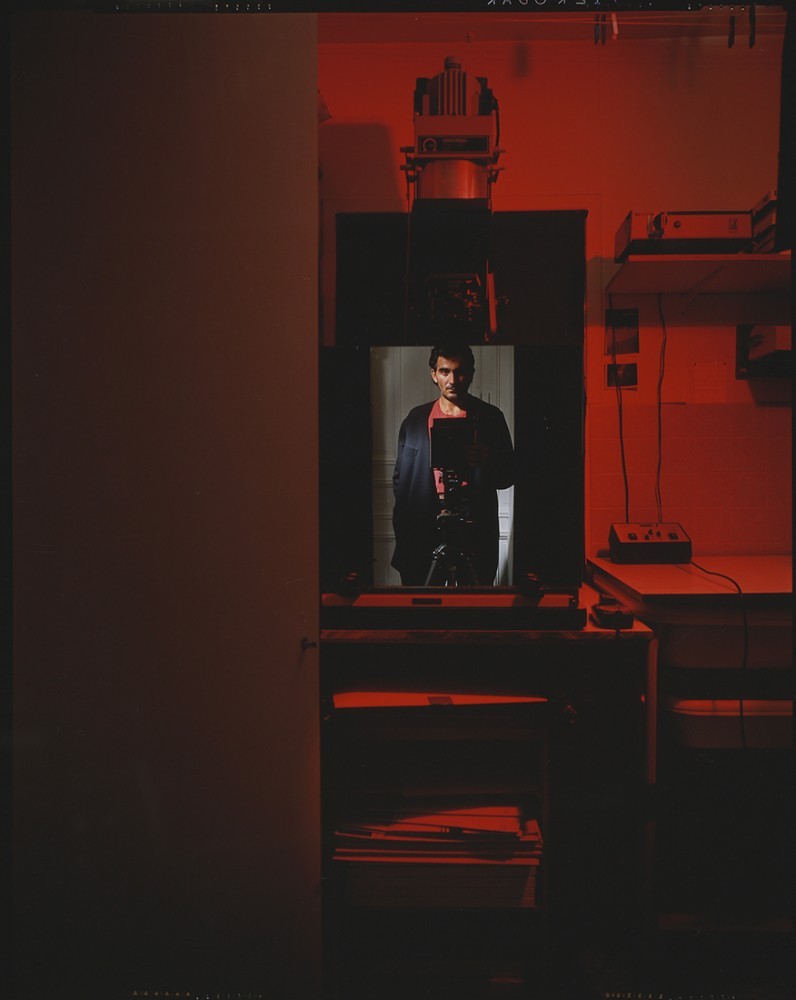

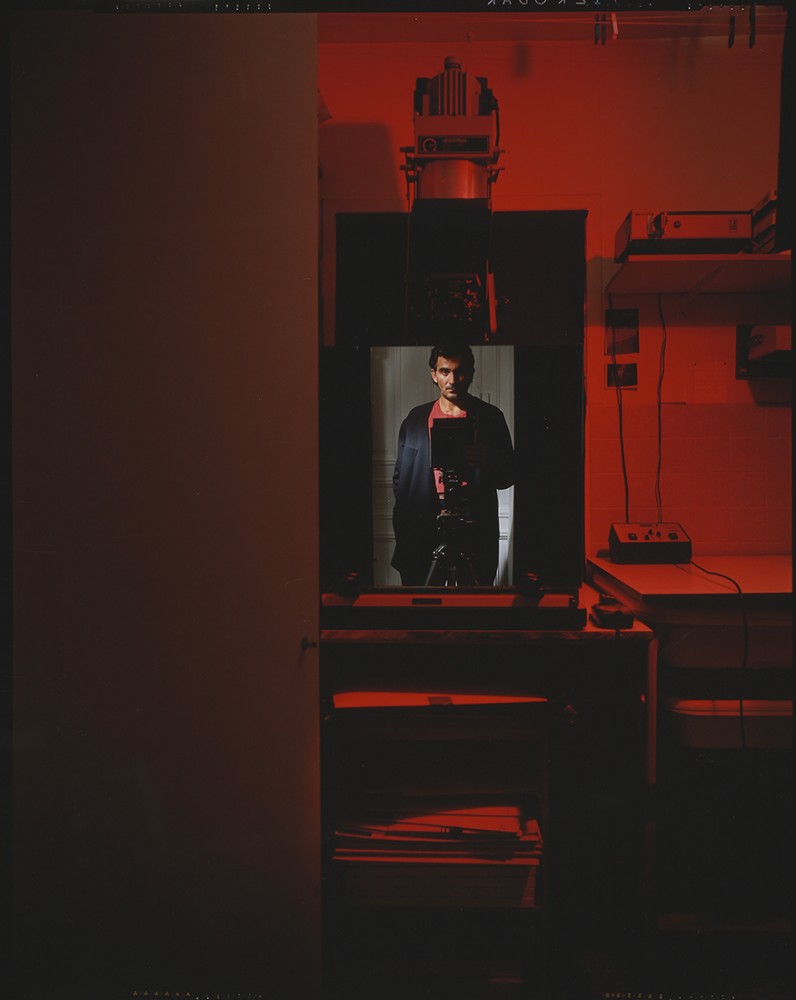

Autoportrait à l’agrandisseur, 1986, Daniel Boudinet, Ministère de la Culture / Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine / Dist. RMN-GP © Donation Daniel Boudinet

They buried him, but all through that night of mourning, in the lighted shop-windows, his books, arranged three by three, kept vigil like angels with outspread wings and seemed, for him who was no more, the symbol of his resurrection.”

Today, seeing Boudinet’s patch of yellow wall in Rome, and knowing what would be his fate — the carnage that cruising would wreak on his generation — one cannot help shiver slightly at this case of life and art imitating each other at one remove, echoing in reflexive reverberation across the memory chamber of time.

Text by Andrew Ayers.

Daniel Boudinet, Le temps de la couleur is on view from June 16, 2018 until October 28, 2018 at Jeu de Paume’s outpost in Château de Tours in Tours, France.