DARK ROOMS: SEX RIGOROUSLY DRAFTED INTO ARCHITECTURAL SERVICE

In 1804, in an anthology of building types conceived to serve a progressive civil society, proto-Modernist Claude-Nicolas Ledoux envisioned the ideal brothel: a phallus-shaped house of sex. In Dark Rooms Atlas, Barcelonans Pol Esteve and Marc Navarro Fornós collected 15 spaces of sexual transaction between men, recording them in the neutral, rarefied form of architectural floor plans. Esteve, an architect, and Navarro, an artist, identify with the political and utopian dimensions of their subject in a kindred way to Ledoux. The darkrooms, they say, are condensed examples of democratic space, “micro-utopias” of free agency, where everyone is client and king.

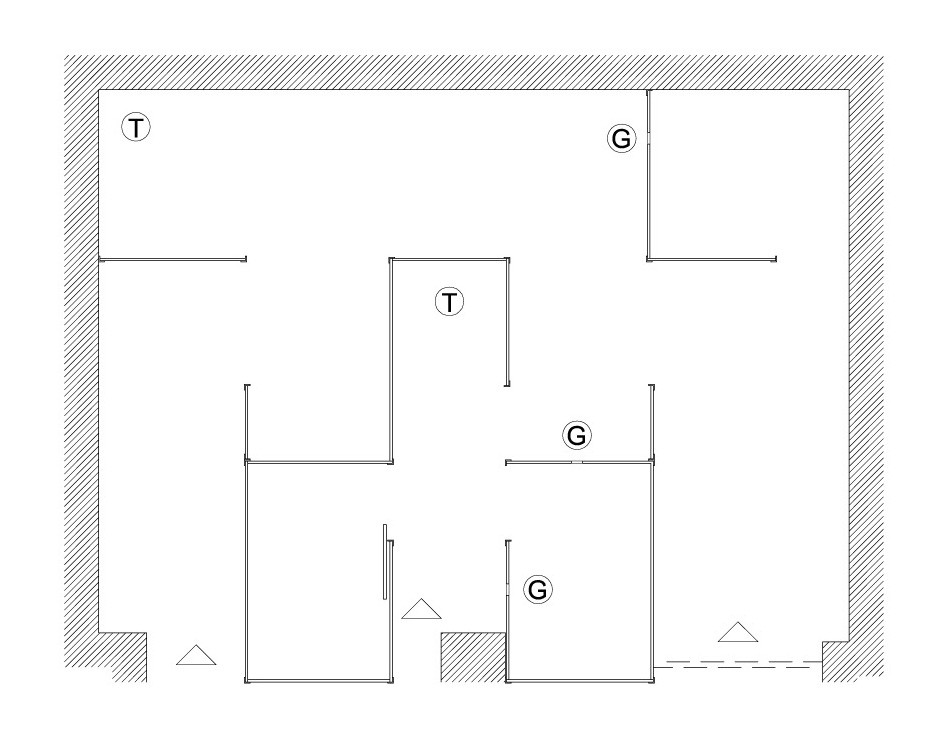

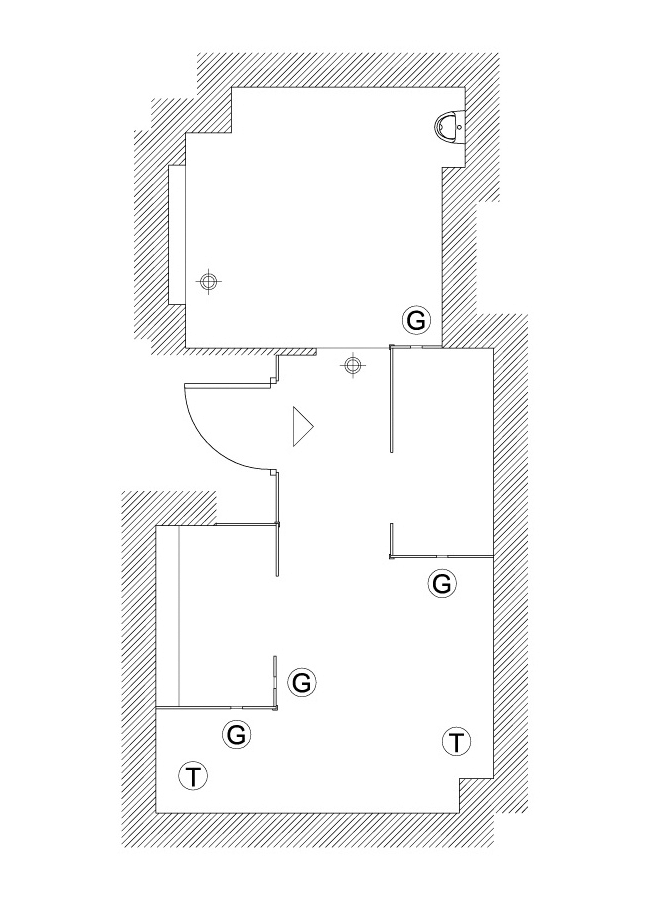

Plan No. 10 is a rational 360-square-foot box with lightweight partitions. Glory holes are marked by the letter G.

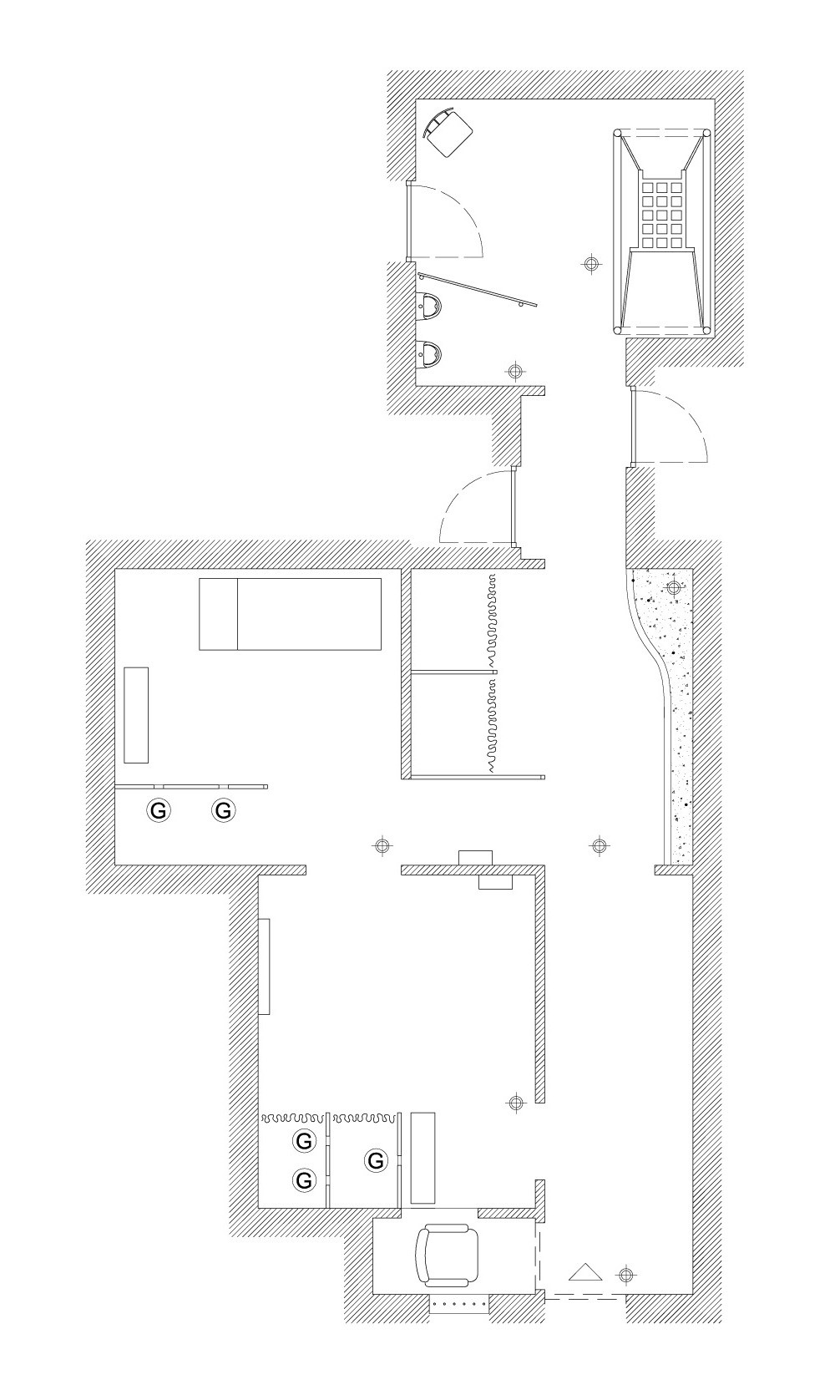

Unlike Ledoux’s brothel, however, nothing in these dark rooms’ form speaks their function. After all, they are not meant for the light. They are “shitty” spaces, as Esteve explains, super-functional small-scale structures reclaimed from the urban fabric. Yet they remain perfectly depersonalized. Scattered around metropolitan Barcelona, they are differentiated by names like Bacon Bear Bar, Salvation, and La Luna. But the differences are only for the cognoscenti; to the uninitiated, they personify little beyond the context in which they are embedded. The basement club Metro, for example, hugs the kinks of an ancient-Roman wall, giving it a recognizably toothy plan. Present and absent at the same time, the dark rooms have a tightly circumscribed existence. Of those recorded by Esteve and Navarro during the summer of 2006, a number have since been closed by the police or forgotten by their clientele, while new locations have surfaced. It was in one of these spaces that Esteve and Navarro met, a “trashy indie gay place” — itself now closed by the authorities — where they spontaneously, in their words, decided to chart the territories the History of Architecture tends to omit. Their efforts have since extended beyond dark rooms to include spaces such as retail changing rooms and ATM booths, forming a picture of furtive intimacy transacted in the dull grey light of the public sphere.

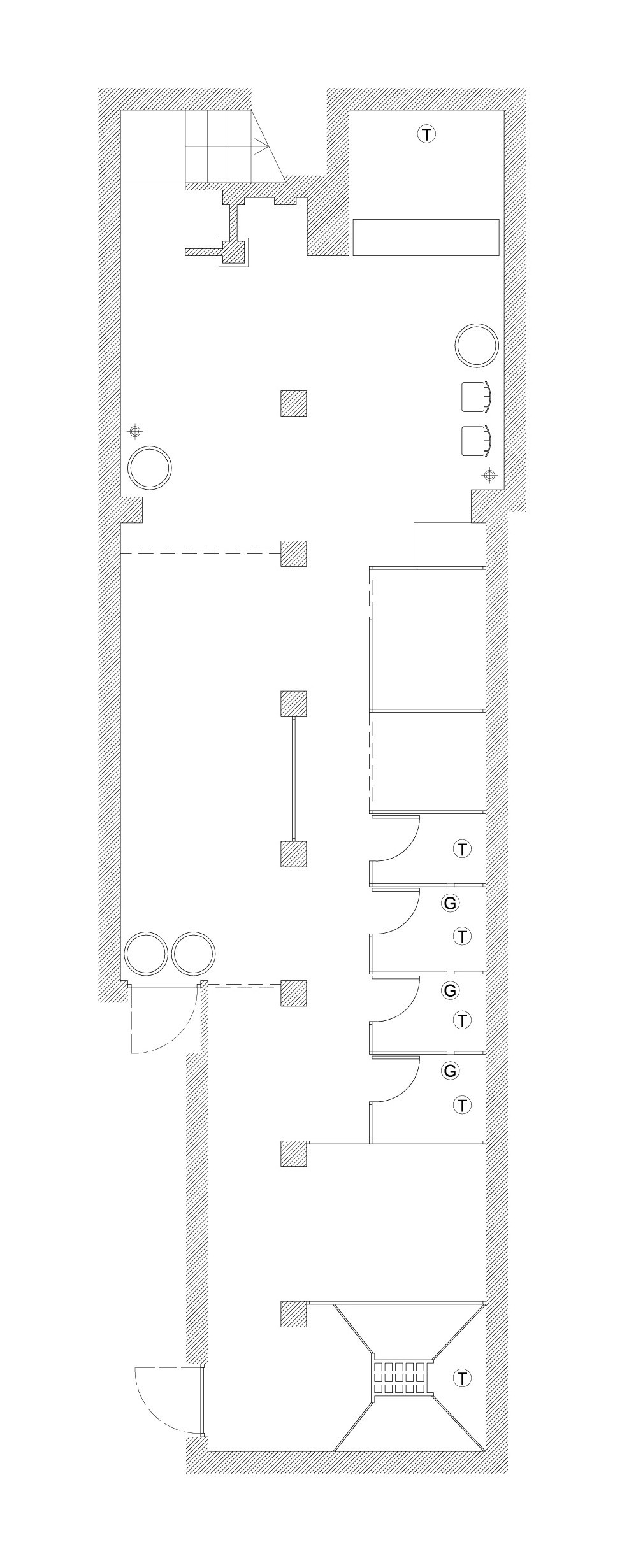

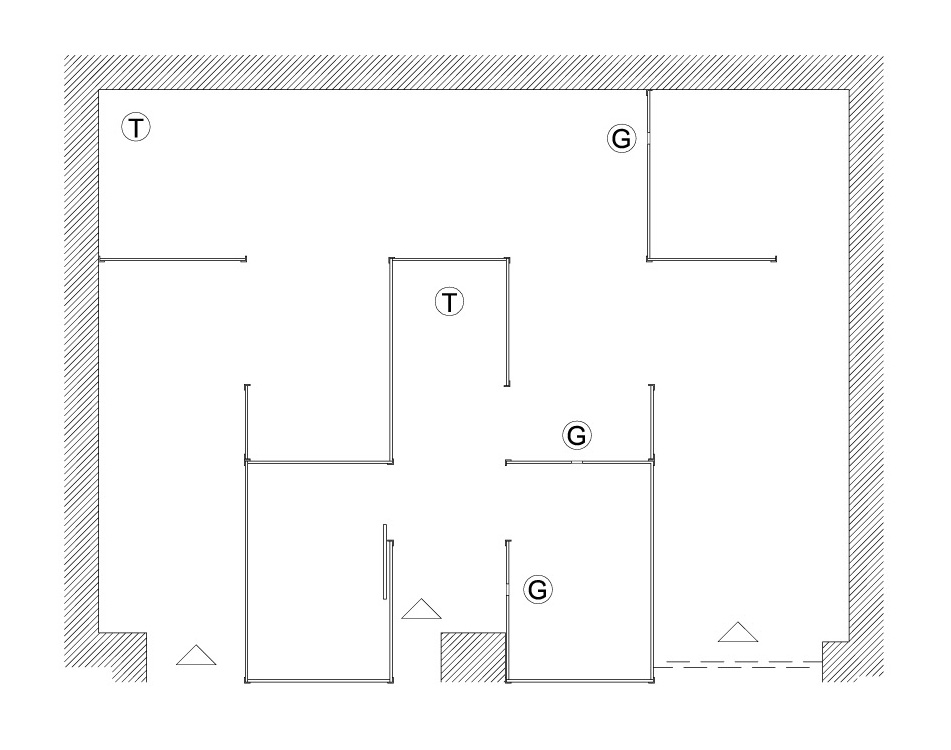

Plan No. 15 is appointed with two slings, five barrels, two tubs, two benches, and a splashing of latex curtains.

Esteve and Navarro describe their method as being like anthropological fieldwork, combining rigorous procedure with the delicacy of leaving their subject almost undisturbed. They surveyed the dark rooms at peak-performance hours, keeping up their professional cool: “While working, we never took our clothes off,” Esteve explains, “though once we were finished it was another matter.” They worked without illumination, waiting silently for the meat-packed crowd to shift or loosen, to vacate a corner or wall. Hours elapsed, sometimes an entire night, before a space could be measured in its entirety. Scavenging the architecture in fragments, like pickpockets, could be a completely disorienting experience, Esteve remembers. In the dark, his imagination easily outpaced his measuring, spaces seeming many times bigger than finally reckoned once on paper. Despite this, and the rampant ambiance, Esteve never felt threatened. “It was all very natural, similar to the way you feel in the supermarket, buying your groceries.”

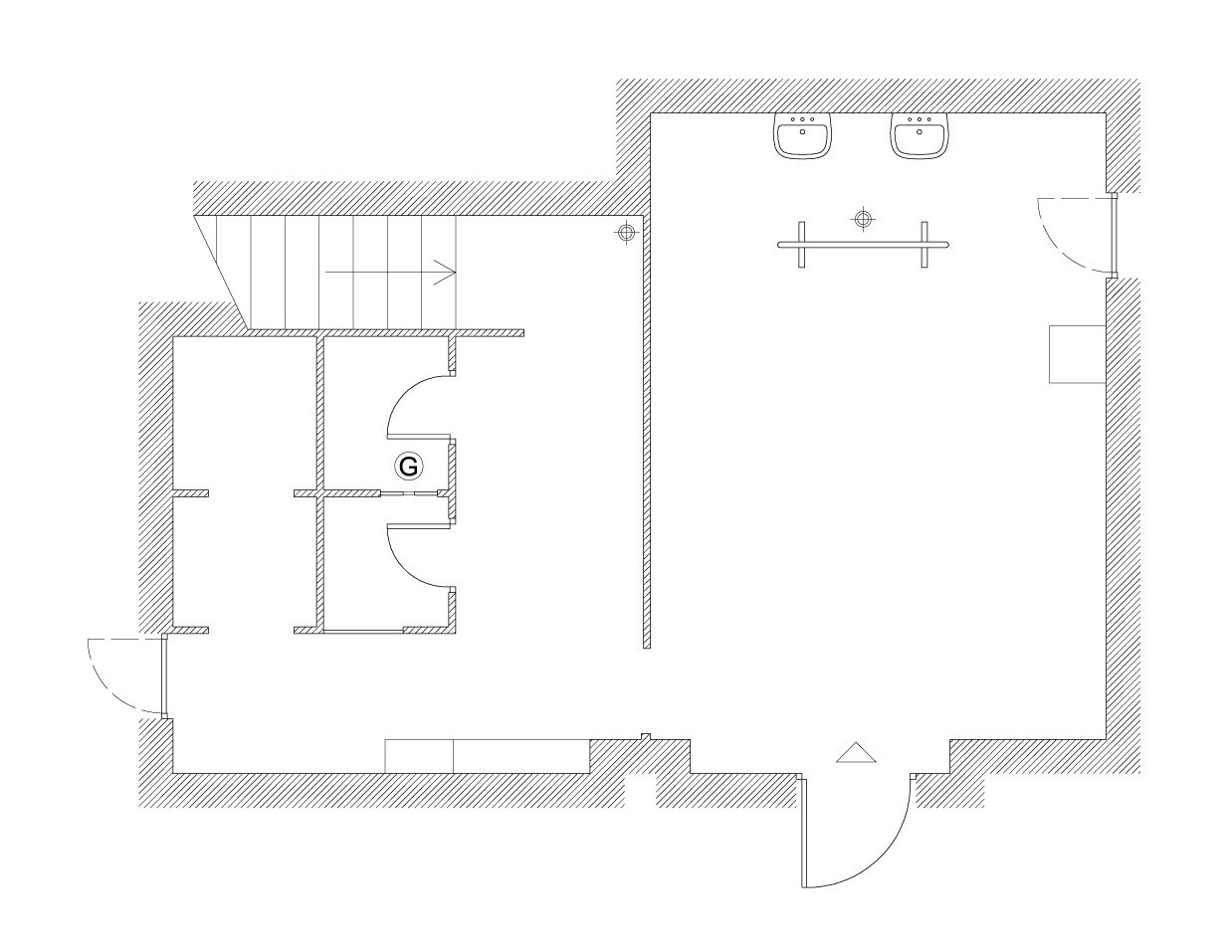

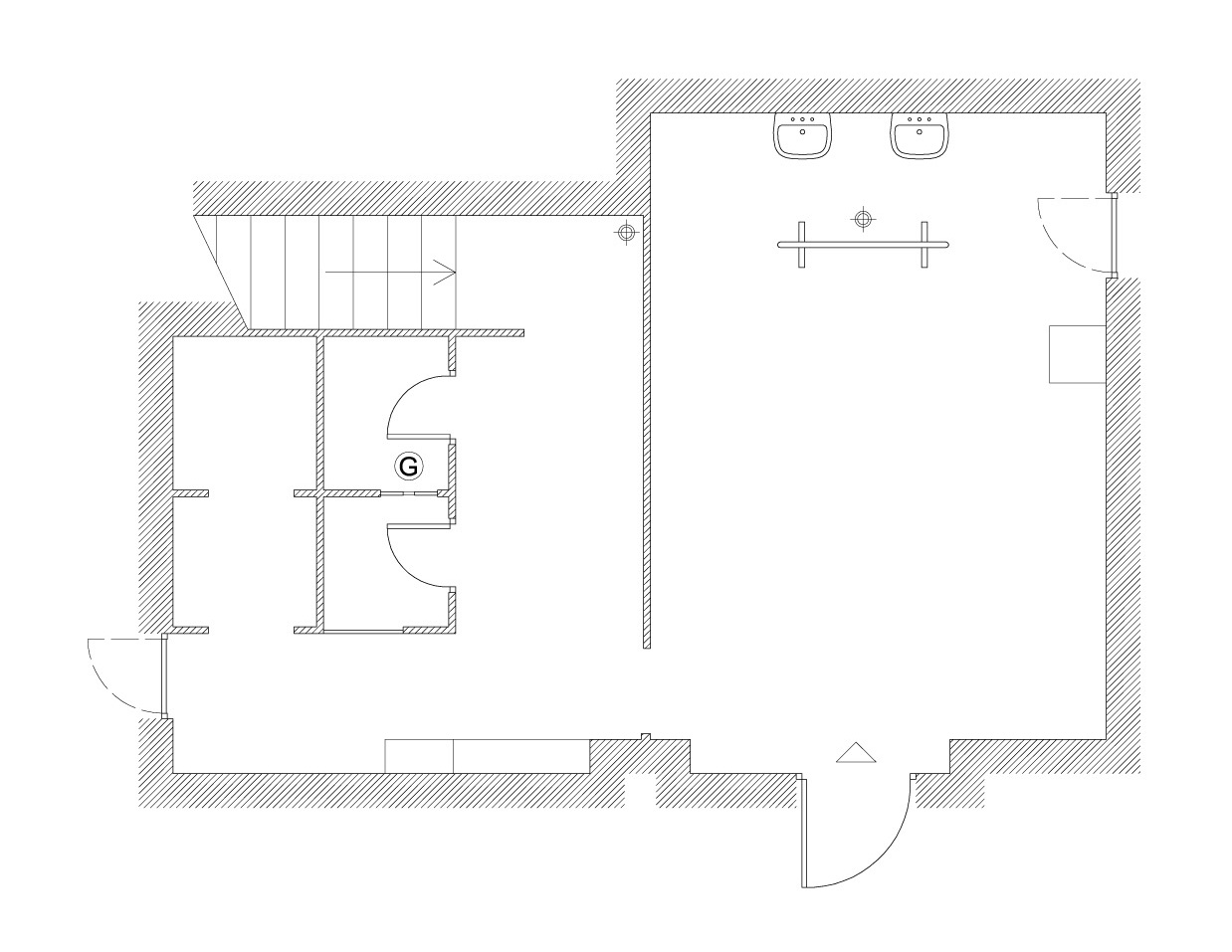

Part of the amenities of Plan No. 11's upper foyer are washbasins for the inevitable rest stop.

If we didn’t know better, Barcelona’s dark rooms could pass as architectural white bread, so classic do they look in the plans of this intrepid duo. But our sense of familiarity with these plans is not just a hallucination. Esteve and Navarro have discovered that the dark rooms embody time-honored Modernist logistics, though perhaps tightened to a hardcore extreme. They are built around well-understood codes and fetishes: economic, anti-decorative, and hyper-functional. But their most gratifying and paradoxical aspect is that they aspire to freedom in each stroke of their simple outlines. Like a New Babylon built of latex curtains and glory holes, slings and barrels — narrative elements that are carefully annotated in the plans — they constitute a DIY utopia of personal expression and a panacea for the collective fear of the unknown. As Esteve and Navarro conclude: “Everything in there is meant to be used in a creative way.”

Text by Pierre Alexandre de Looz. Images by Pol Esteve and Marc Navarro.

Taken from PIN–UP 6, Spring Summer 2009.