ISSUE 38 S/S 2025

PIN–UP XXL. The Big Design Issue. Design is often reduced to surface, function, or price tag. But how do we choose which objects deserve space? What resonates with you and the people you share that space with? What challenges our ideas of taste, of design’s role in the world? The PIN–UP XXL issue is not just supersized — almost double the size of a regular PIN–UP — it is also an expansion of how we approach design. Think big!

VIEW ISSUE →

Story

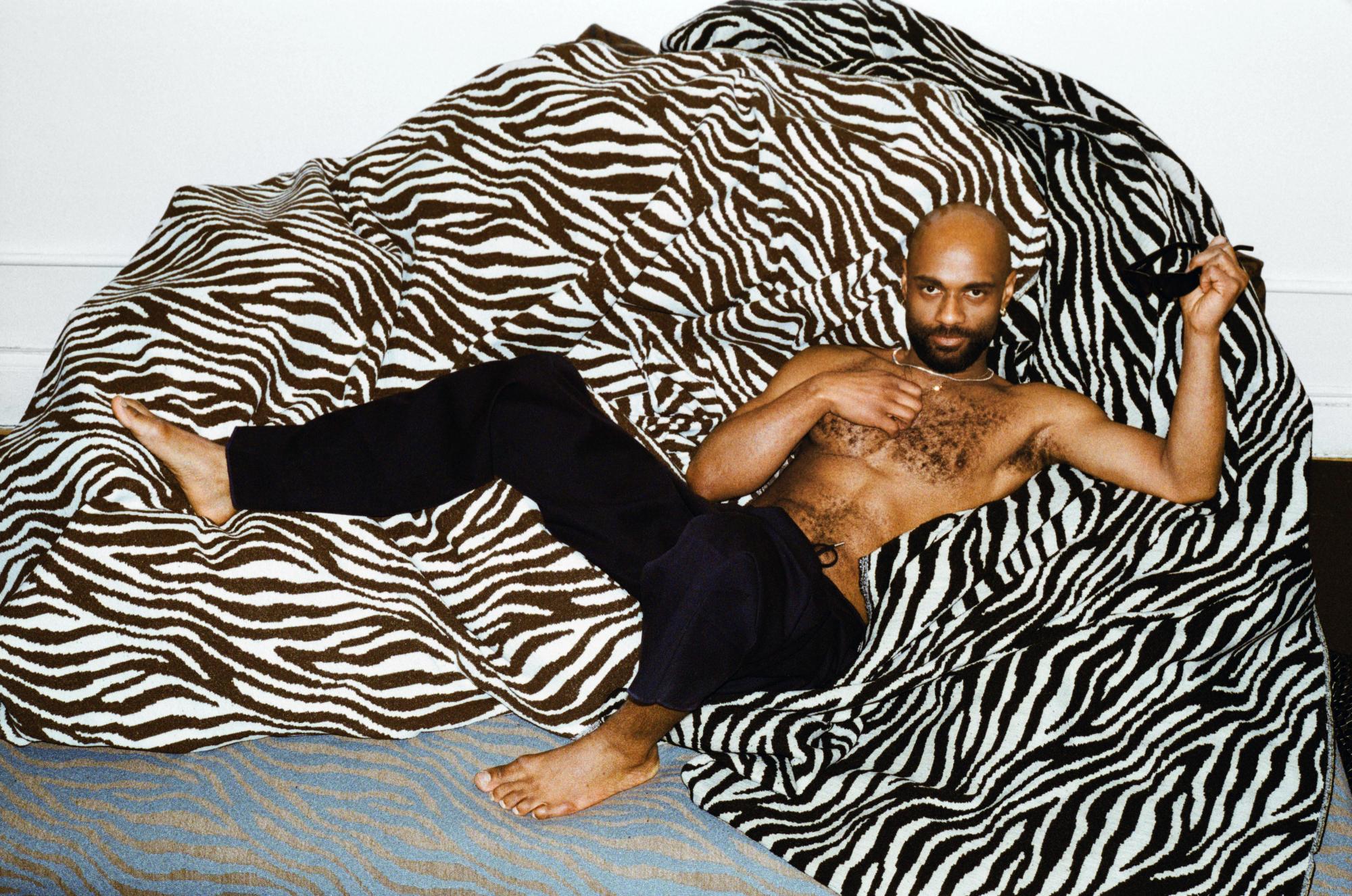

TALKING TEXTILES WITH MARK GRATTAN

by Felix Burrichter

Story

JONATHAN MUECKE’S NEW ALL-WOOD COLLECTION FOR KNOLL

Story

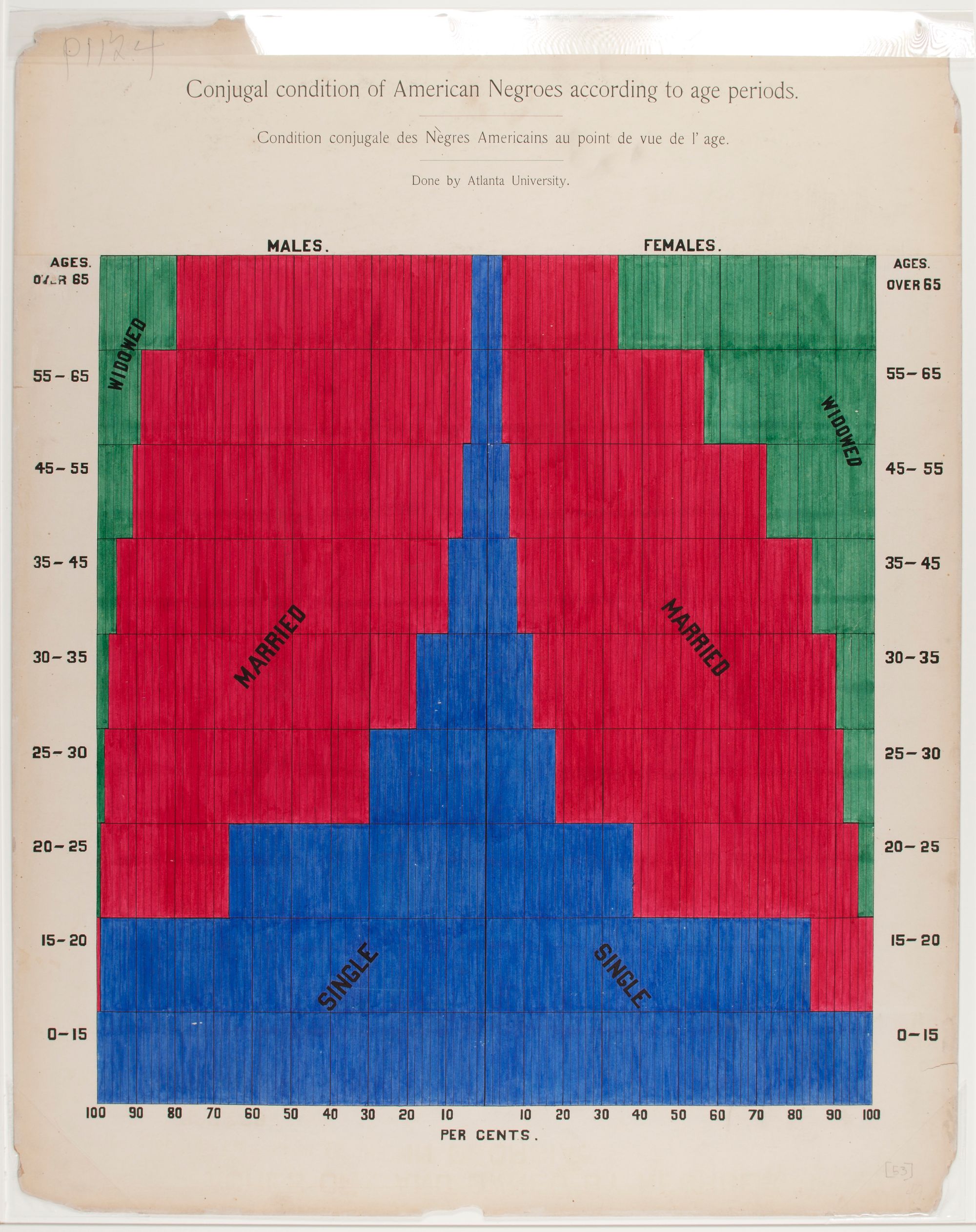

DATA DRAMA AT FONDAZIONE PRADA

Interview

PIERO GANDINI'S RETURN TO FLOS B&B ITALIA GROUP

Interview

THE ARCHITECT WHO BUILT SNIFFIES

by Michael Bullock

Story

11 NYC CREATIVES CONNECTING THE DOTS BETWEEN ART AND DESIGN

by Rachel Hahn, John Belknap, Caroline Tompkins

Interview

AN INTERVIEW WITH FAYE TOOGOOD

Story

AN ARCHITECTURAL STAGING OF THE MIU MIU WOMAN

Interview

AN INTERVIEW WITH FISH DESIGN’S ANDREA CORSI

Story

DUYI HAN’S INTERIORS ARE FIT FOR A QING

Story

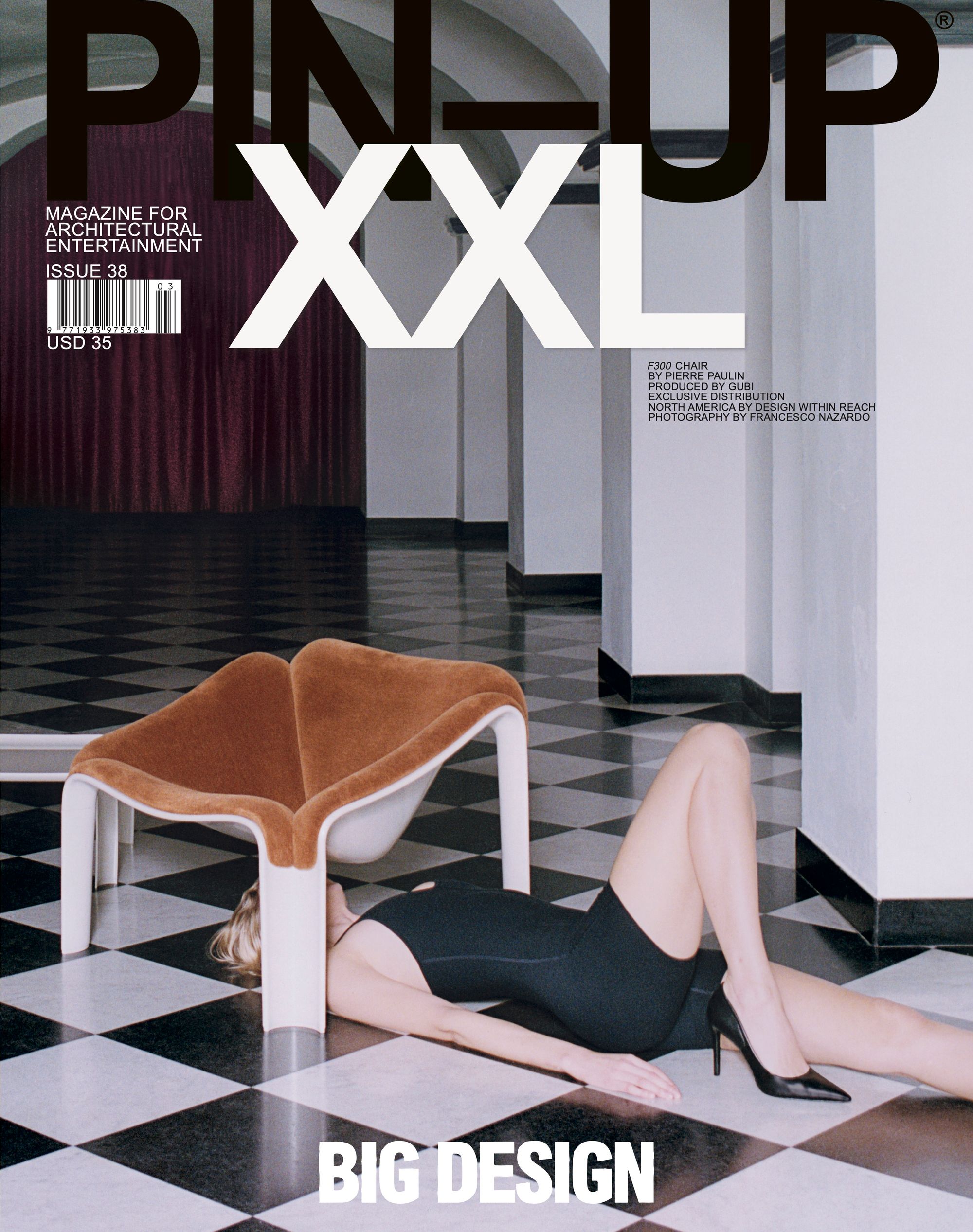

PIERRE PAULIN’S ICONIC F300 CHAIR IS BACK

by PIN–UP

Story

20 YEARS OF THINKING BIG WITH PLAYLAB

Story

FAYE TOOGOOD’S SOFA FOR TACCHINI OFFERS COSMIC COMFORT

Interview

DESIGNING 25 YEARS OF PAUL PFEIFFER

Story

CHARLAP HYMAN & HERRERO’S GLASS SUBJECTS

Story

INSIDE THE HOME OF LATE JUAN PABLO ECHEVERRI, A POP CULTURE MASTERWORK

by Michael Bullock

Interview

SMILJAN RADIĆ’S FRAGILE VISION OF ARCHITECTURE

Story

Bolivia’s Cholet Culture Caught Between the World’s Leading Economic Forces

Interview

ANDY MEDINA FINDS NEW LANGUAGE IN SYMBOLS AND MONUMENTS

Interview

AN INTERVIEW WITH MARTINE SYMS

Story

THE XXL PORTFOLIOS

by PIN–UP

Story

LIVING MUSEUMS AND THE POSTMODERN PILGRIMS OF PATUXET

by Rachel Hahn

Story

PATTI SMITH CONJURES THE SPIRIT OF CARLO MOLLINO FOR BOTTEGA VENETA

Story

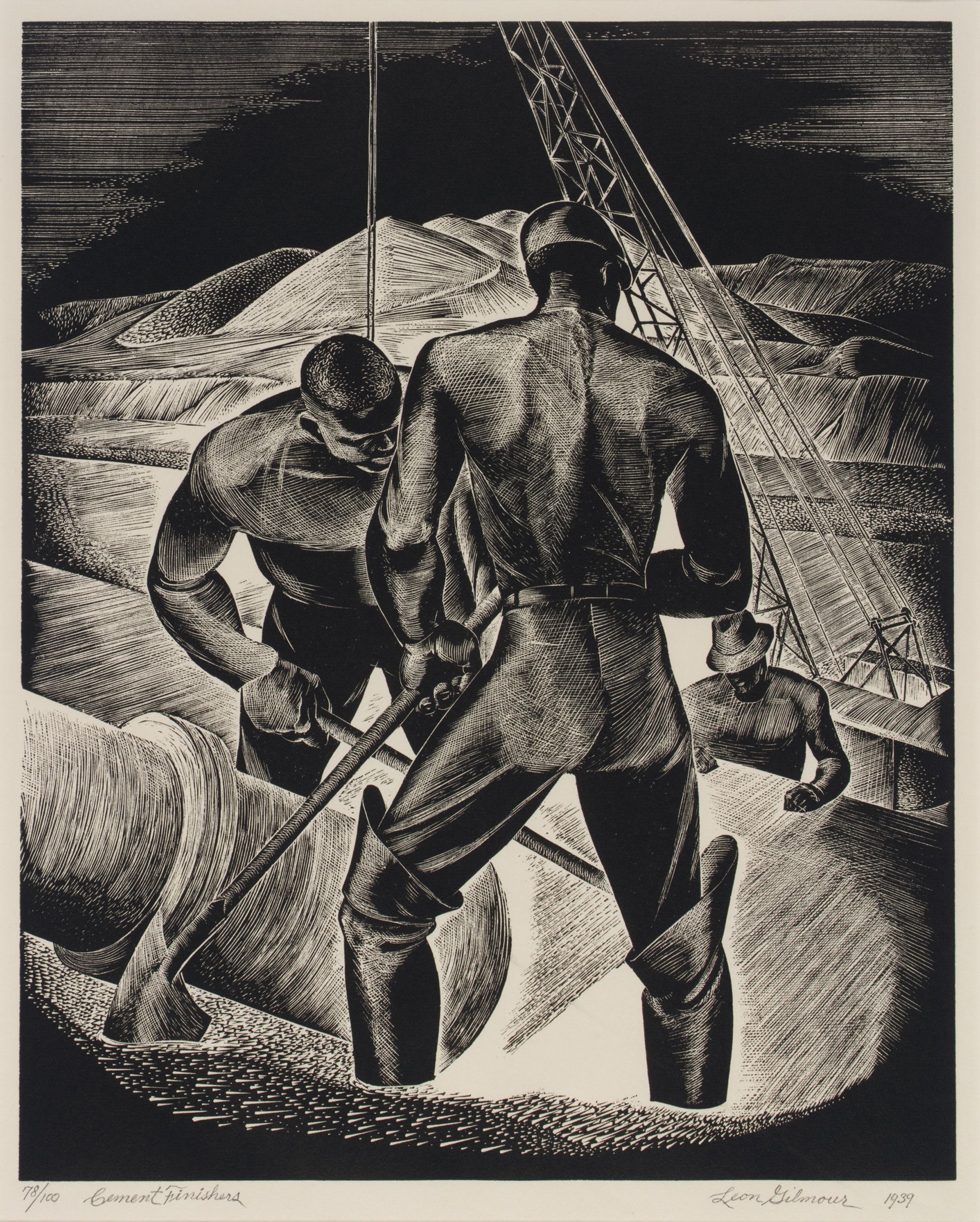

CURATOR ABRAHAM THOMAS ON SIX WORKS THAT DEFINE PAUL RUDOLPH’S CAREER

Story

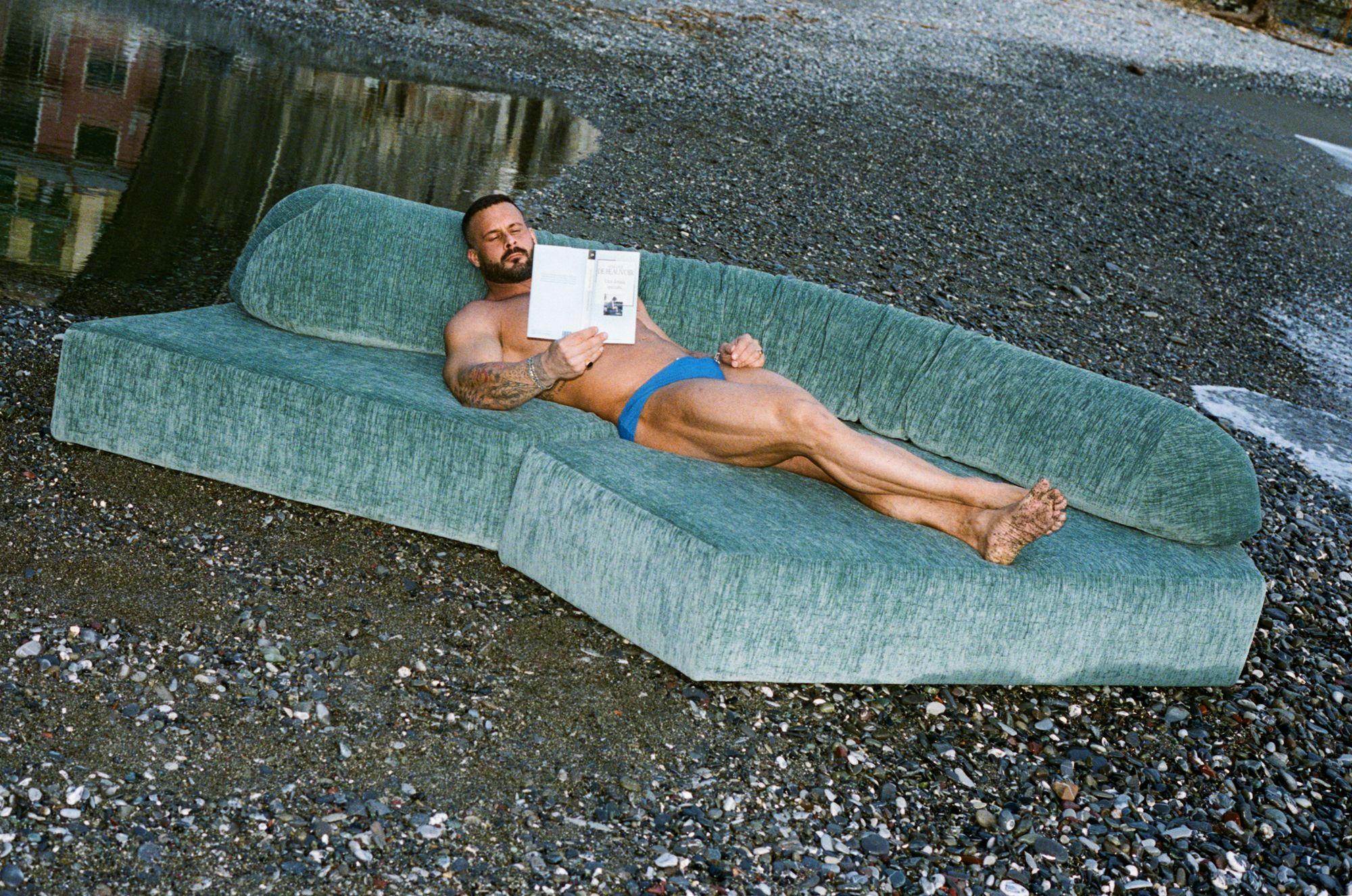

TRAILING HOMOEROTICISM ALONG THE URBAN SITE

Interview

FOR ITSUKO HASEGAWA, ARCHITECTURE IS SECOND NATURE

Story

INFINIMENT COTY PARIS: A STORY OF TIME AND SPACE

Story

BLU DOT’S OUTDOOR COLLECTION IS A PERENNIAL CLASSIC