CALCULATED DISORDER: Carsten Höller Puts On A Delirious Show in Mexico

It was just after noon in Mexico City and the sun was high, glinting off an indistinct object sprouting from the rough concrete of Museo Tamayo. Having forgotten my sunglasses, I had to shade my eyes to try and make it out while Carsten Höller’s transitions lenses darkened as he looked right at it and into the sun. The Stockholm-based German artist spoke in a near whisper explaining the history of the fly agaric mushroom, which it turns out had inspired that shadowy thing protruding from the museum’s roof, his sculptural interpretation of the fungus artistically crossbred with some others mounted directly above the director’s office. The fly agaric mushroom was possibly so named (across many languages), Höller said, because it attracts flies. Or maybe it got its name because medieval Europeans thought that when you went crazy, it was because you had flies in your head. The mushroom, psychedelic, does make you a certain kind of crazy. A fly buzzed by and landed on the person standing to Höller’s left. “See? I can communicate with them,” he laughed. Höller wrote his dissertation for an agricultural sciences PhD on the olfactory senses of insects, so there may be something to this claim.

Giant Triple Mushroom by Carsten Höller installed atop Museo Tamayo. Photo by Pierre Björk.

The mushroom is a curious thing. Born of decay — delicacy, death, delirium all stem from it. It is the third that concerns us here. In 1927, Gordon Wasson was honeymooning in the Catskills when his new wife, Dr. Valentina Pavlovna Guercken, dug up some edible mushrooms. With their two different backgrounds — Wasson was born in Montana and Guercken in Russia — the pair became fascinated by cultural differences in views towards mushrooms, and the respective publicist and pediatrician fashioned themselves ethnomycologists.

And there is a particular Mexican connection. In an expedition later revealed to have been funded by the CIA as part of the MKUltra project, the agency’s mid-century experiment in mind control that often relied on the willing and unwilling dosing of psychedelics and other drugs, the couple traveled to Mexico to commune in a shamanistic ritual with the curandera María Sabina, during which they ingested magic mushrooms.

Hallucinogens have been cultivated and used across cultures and their prohibition is only relatively recent. For Höller, the early human ingestion of plant-based intoxicants is, in a way, the birth of culture — the production of an understanding that there could be, that there in fact was and is, something else, a possibility latent within our own minds, a space of difference.

The museum is a space of difference, too. In this exhibition, perhaps even more so. A sort of high-brow M.C. Escher, Höller’s retrospective, Sunday, at Museo Tamayo is about misunderstanding ourselves to understand ourselves better. The show’s centerpiece is Decision Tubes, a series of suspended interlocking knit tubes that traverse the museum’s central atrium, an update to Decision Corridors first shown in 2015 in London. It would be a total Instagram trap if taking photos inside weren’t forbidden.

Carsten Höller, Decision Tubes. Photo by Pierre Björk.

If psychedelics bridge and break synapses, forging connections between formerly discrete regions of the brain, then these tunnels do much the same to the museum’s architectural logic, exposing the inherent structural fragmentation of rooms, regions, and floors, by unifying disparate parts and transgressing their usual boundaries, while suspending bodies, like so many electrical impulses, in the air: I moved through gleefully and fast, others cautious, trepidatious, holding on for dear life.

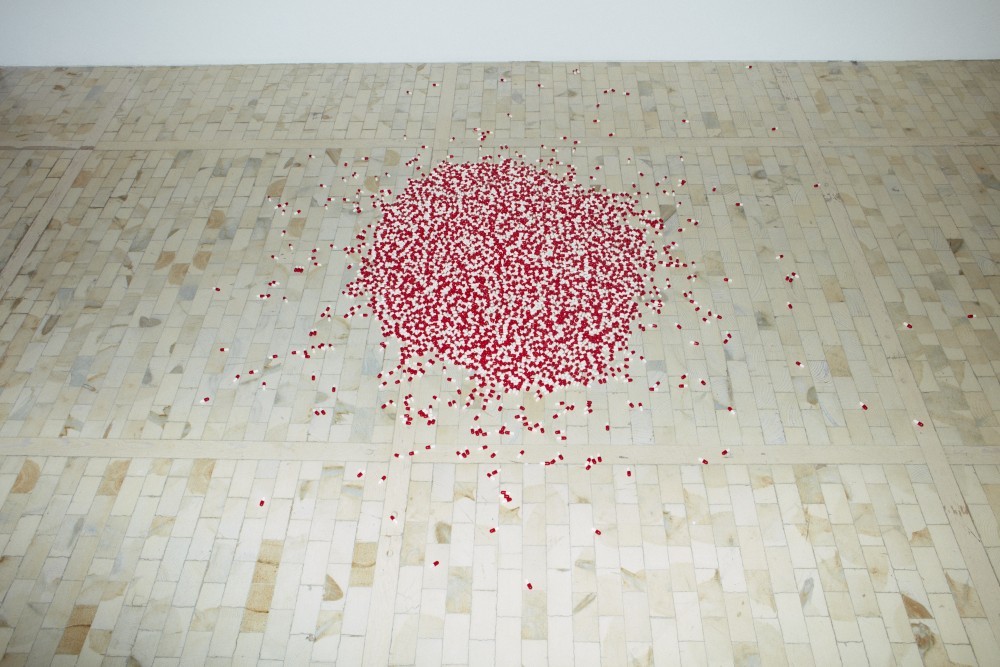

The traversable Decision Tubes was hardly the only interactive piece in the exhibition. In Pill Clock (red and white pills) (2015), red and blue pills fell from the ceiling and into a pile on the floor, like a pharmaceutical re-imagination of Félix González Torres’s candy portraits, and like the candy portraits, you were invited to take one. I assumed that the gelatin capsules must have been empty, but when I pinched my pill, white powder came out. I poured some water from the tap hidden in a wall into a flimsy paper cup and swallowed. I don’t think I felt any particular chemical action after ingesting the mystery capsule, but I did feel a certain nervousness, and giddiness too. In a place so normally defined by rules and order, the museum, it felt wrong, which, of course, was the fun of it all.

-

Carsten Höller, Pill Clock (red and white pills) (2015). Photo by Pierre Björk.

-

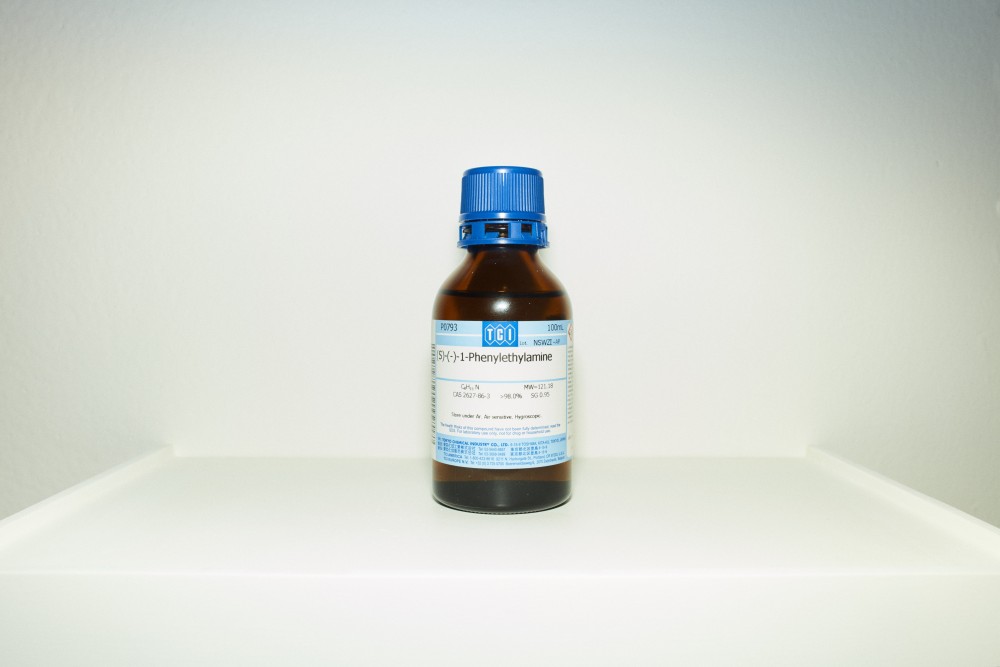

Carsten Höller, Love Drug (PEA) (1993/2001). Photo by Pierre Björk.

Not restricted to oral intoxicants, the exhibition also featured an inhalant. Mounted on a white cube-white shelf was a chemical labeled "(S)-(1)-Phenylethylamine." It smelled fishy and unpleasant but its stench supposedly made you more friendly. At the opening, a famous and gregarious artist — who will remain unnamed at his own insistence — said he had never talked so much in his life and asked me if I’d come huff some more of the substance with him. I walked over to the shelf, unscrewed the blue cap and sniffed, hard, using my index finger to close my right nostril then my left. The high wasn’t as good as amyl nitrate, but it was okay. In previous installations of the work, marriages developed from strangers who had met waiting in line and imbibed together. The artist said his ex-girlfriend had my same shoes. I remain single.

Of course, Sunday’s calculated disorder was not relegated to the chemical. One of the most jarring experiences was Seven Sliding Doors (2004), a series of seven automatic mirrored doors, which only opened as you got extremely close. They made you wait. When one door slid open slyly to reveal just a further field of mirrors, if someone else happened to be passing through the opposite direction, they took the spot where you had just been and the floor seemed to drop out beneath you in a moment of confusion and ego death — suddenly reflected at you was an unfamiliar person where you expected to recognize yourself. Humans may be one of the few animals that likely recognize themselves in the mirror but it is always already a misrecognition, anyway. (Carnival fun houses take note.)

But it is not just ourselves but our world that becomes strange in Sunday. Just through Seven Sliding Doors is a large array of LED bulbs mounted to the wall, an update to 2000’s Light Wall. They pulse at a rate of 7.8 hertz, a speed which Höller chose for its supposed soothing effects on the mind. Standing among them produces a sort of hallucinatory visual field, like a gentle version of a migraine aura. Out of speakers a phantom voice speaks, on one side saying, in German, green, on the other, yellow. Together they sound like neither, and the orderliness of naming things and putting words to the perceived world is disrupted. A vitrine of golden mushrooms titled 7,8 Hz (The Color of Gold) (2004) features a smaller version of these pulsing lights, which have the effect of making the gold-leafed surfaces of the more-true-to-life-size fungi dance.

Cartsten Höller, 7,8 Hz (The Color of Gold) (2004). Photo by Pierre Björk.

The flashing lights flush the surrounding space with a constant visual whir. The Division Circle and Division Square paintings, something like Mondrians, though with greater systematicity, are lit and then not, but so fast as to not flicker, but to vibrate. These paintings are simple, rule-based things, a half, then half that half, and so on, till the halving disappears into itself. An asymptote visualized, they figure the limits of depicting infinity. The cap of the outdoor mushroom is cut and fragmented with a similar logic. Downstairs, there are the Dot Paintings, which though seemingly random, are in fact depictions of famous kisses from photos and film, each body represented methodically with a spot marking specific points like the hands or the head, a fact only made clear in their parenthetical titles, like Breakfast at Tiffany’s Kiss. Order and disorder are made simultaneous, revealing the artifice of both.

Despite all this whimsy, and for all our willful participation, throughout Höller’s retrospective, there is a sort of coercion. Lights one can’t escape, mirrors one can’t look away from; tunnels that leave you stranded in alien parts of the museum; a wooden sculpture that to get inside you must touch it, push it away from yourself as it pushes back. The sculpture, Swinging Spiral, ringed like the inside of a shell, if you stay inside its swaying disrupts your body’s relationship between its proprioception and vision, unsettling the ground beneath you. The real tyranny is that of our own perception, its limits, and the ease with which the introduction of the unexpected can reroute our understandings of reality, and thus, sow seeds of doubt in the abilities of our own minds and senses to grasp it. Seeing wrong is just seeing different, seeing difference as possibility. All this forced synesthesia reveals not the mind’s limits but its potential.

Museums themselves have their own dictatorial tendencies. And at first, Sunday, with all its touching and sniffing and climbing may seem to resist this. But, of course, it is just a new set of rules. This is the point. In this exhibition there is the art, of course — some of it interactive — but also on display are the visitors, there to be witnessed and to witness you too. And, even one step further in this dissociative display, it’s not just others you see; you view yourself as a stranger, too.

We end, by going to sleep, or really, by waking. Towards the back of the exhibition are two beds, similar in dimensions to those of a hospital, though outfitted with greater conveniences, like a phone charger. Both are on wheels and have attached to them a marker, one bed’s blue, the other’s red. Slowly, these beds migrate around the space, automated and regulated by a sort of internal-GPS system. Though not immediately clear, one bed is always leading the other which mimics its motions at a slight delay, till one is stuck and the other must take control to rescue it. There is always a subtle tyranny to the work, after all.

Installation view of Carsten Höller's Sunday. Photo by Pierre Björk.

For just over $250 each, two guests can spend the night in the beds. Before they sleep, they’re given a special toothpaste, Insensatus Vol. 1 Fig. 1 (2014), made in Austria of herbal extracts of undisclosed origin. There are four tubes, one an activator, and then three that each offers a unique direction for your dreams: male, female, or child. The pastes can be blended. When the guests awake in the morning, or if they do during the night, they’ll be in an entirely different location in the space, like blacking out and waking up in a stranger’s bed only stranger still for being uncannily close to where they began. Then they’ll be brought breakfast. Overnight the robot beds’ paths will have been drawn on the museum’s floor. The toothpastes are available for purchase in the museum gift shop.

Text by Drew Zeiba.

Photography Pierre Björk.