GHOST ON THE HIGHWAY: ALLAN D’ARCANGELO’S HAUNTING AMERICANA

Sick a psychic on America and they’d head for the highway. Reading the interstate’s snaking expanse is a lot like reading palms: through the scars of its disused routes and roadside detritus, deep cuts of commercial pressure points, mega-mall rest stops, and tacky billboards, Americana breaks down, equal parts monotonous and sublime. From the ecstatic narratives of tripping Beat poets to photographer Catherine Opie’s famed Freeways (1994) series that pushes the underbelly of L.A.’s infrastructure into the spotlight, artists have long sourced inspiration from the mythological American interstate; the drawings and paintings by the late Allan D’Arcangelo’s (1935–97) are a fundamental but still underexposed part of that vision.

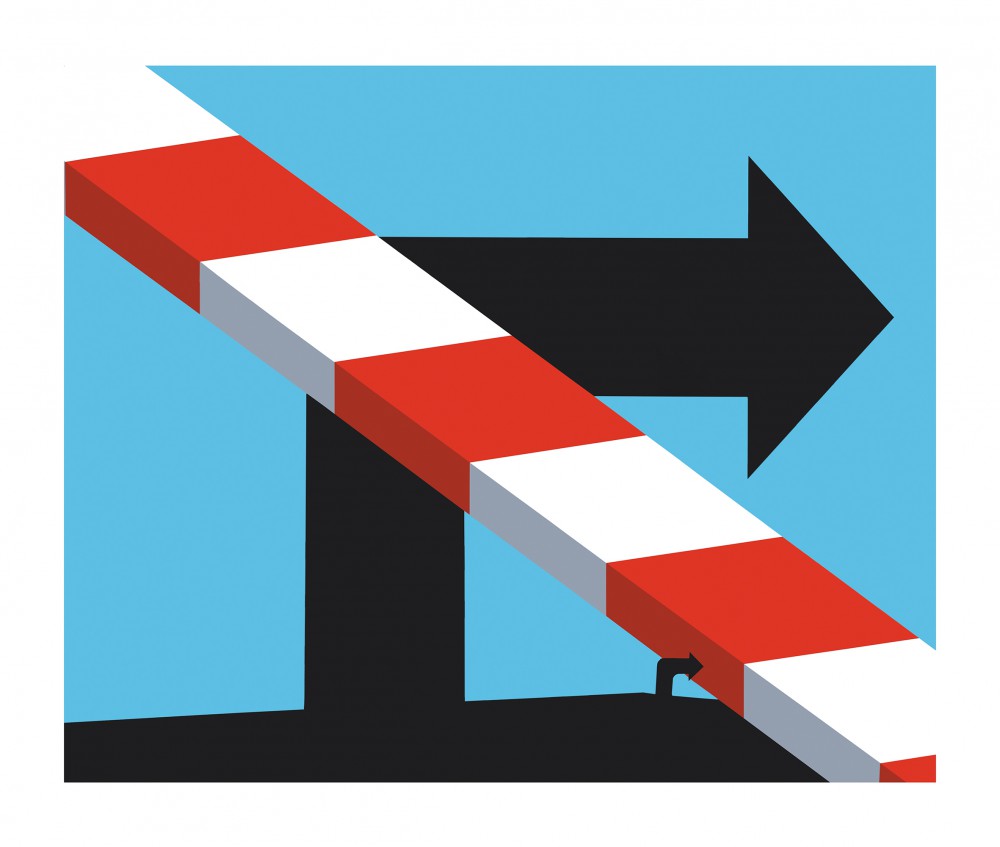

Allan D’Arcangelo, Pi in the Sky, 1981–82

While D’Arcangelo always considered himself a “peripheral figure” to Pop darlings like Warhol and Lichtenstein, his brooding and stylized landscapes of American altered consciousness overlap Pop’s interest in the surface, brand aesthetics, and graphic abstraction. A half century on, the darker personality of D’Arcangelo’s work has evolved beyond that of his contemporaries in unexpected ways; his work’s refusal to yield to a single interpretation takes on new relevance within the country’s equally obfuscated political moment. From this perspective, Pi in the Sky, currently on show at Waddington Custot in London, reframes an elegant and provocative selection of D’Arcangelo’s work spanning from the late 1960s to early 80s.

A born-and-bred New Yorker, D’Arcangelo spent his due time trawling through the Bible Belt of the Deep South and the dizzying expanse of the Southwest desert as well as the more expected outposts of New York and L.A. Taking a particular favor to the way acrylic interacts with light — how it avoids the glistening sheen of oil, and how the flatness of the medium masks the presence of the artist’s hand — D’Arcangelo teases out complex ideas of the highway’s reality and representation, its rampant commercialization and maddening isolation, as well as escapism and entrapment as two split personalities of American infrastructure space through his signature flattening one-point perspective.

Allan D’Arcangelo, Untitled (Landscape), 1967.

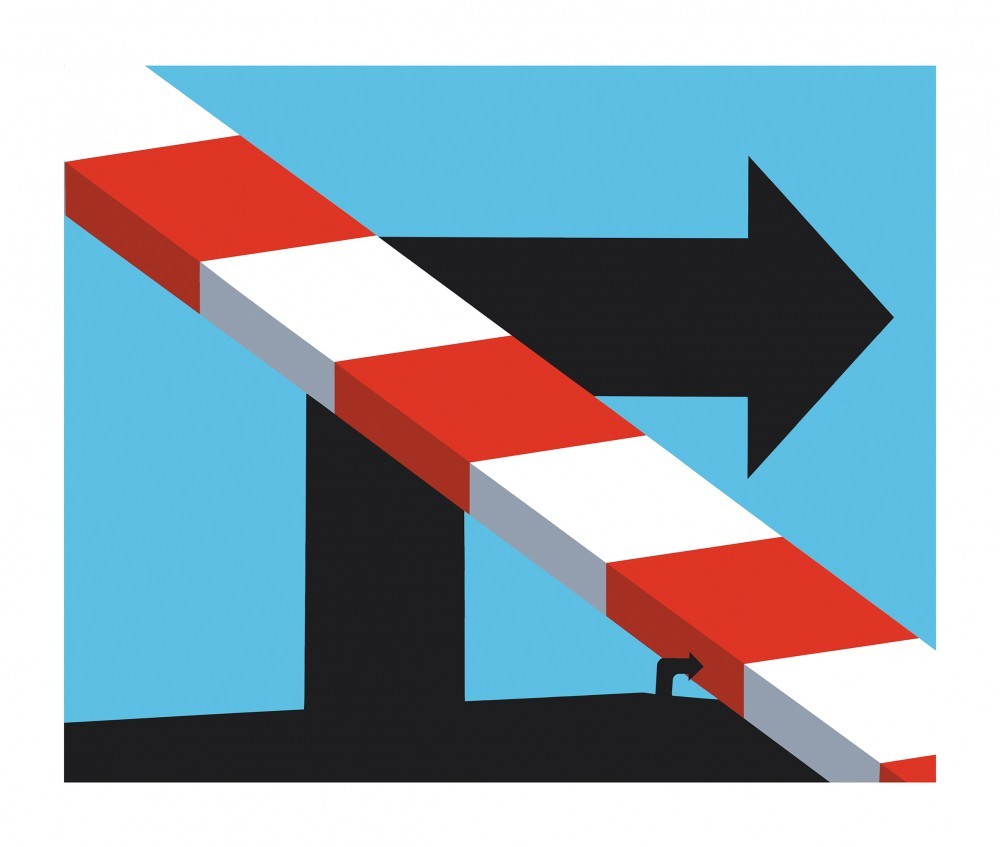

“My most profound experiences of landscape were looking through the windshield,” D’Arcangelo explained to Marco Livingstone in the spring of 1988 while the two drove from New York City to the artist’s studio in upstate New York: an idiosyncratic interview included in the exhibition catalogue. “The sky, the tree line and the pavement all have the same quality, and it has to do with our separation from the natural world.” Far from the sugar highs of Pop and the exit strategy fantasies of the freeway celebrated by Kerouac’s crew, D’Arcangelo’s work breaks down its iconography, re-assembling these symbols and signs into a world that is legible but impossible to navigate.

Standing in front of a baby blue canvas where two right-turn signs screw with the depth of field like a game of snakes and ladders, the playful resistance of his work to logical interpretation is laid bare. Even the painting’s name, Untitled (Landscape) seems to be having a go: suggesting that it can be read in any straightforward sense. “A double take is built into the painting,” suggests Barry Schwabsky in the opening essay of the exhibition catalogue. “Not to arrive at a resolution but to make you feel the way time undoes your certainties.”

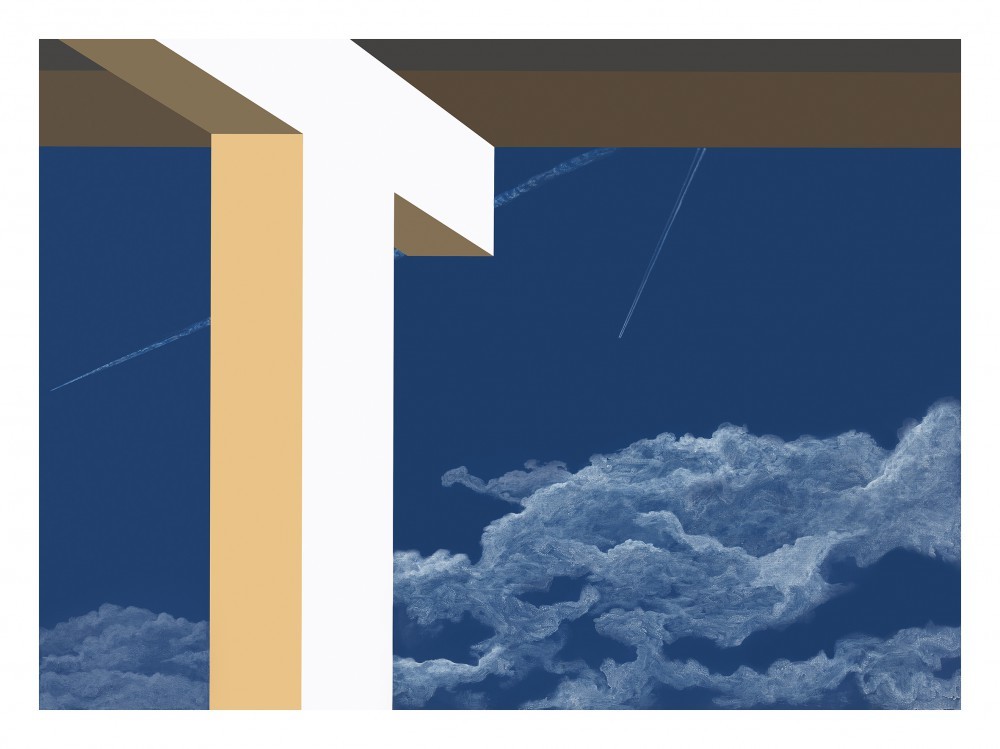

Allan D’Arcangelo, Without Sound Two, 1982.

Inside the main room of the gallery, the monolithic Without Sound Two (1982) and Ninosum (1974) are locked in an epic face-off. The former gives a sense of isolation that’s vaguely optimistic, with faint lines of jet planes shooting off in an upward gaze that seems counter the lofty overpass of the elevated freeway framing the top of the painting. Meanwhile the bruise-hued purple and pared-back iconography of the latter is deeply somber; it swallows up the spotlight of the gallery like a black hole. Still, there’s a weird spiritual energy that glows and grows with the more attention it gets, almost reminiscent of Rothko that’s obediently colored inside the lines.

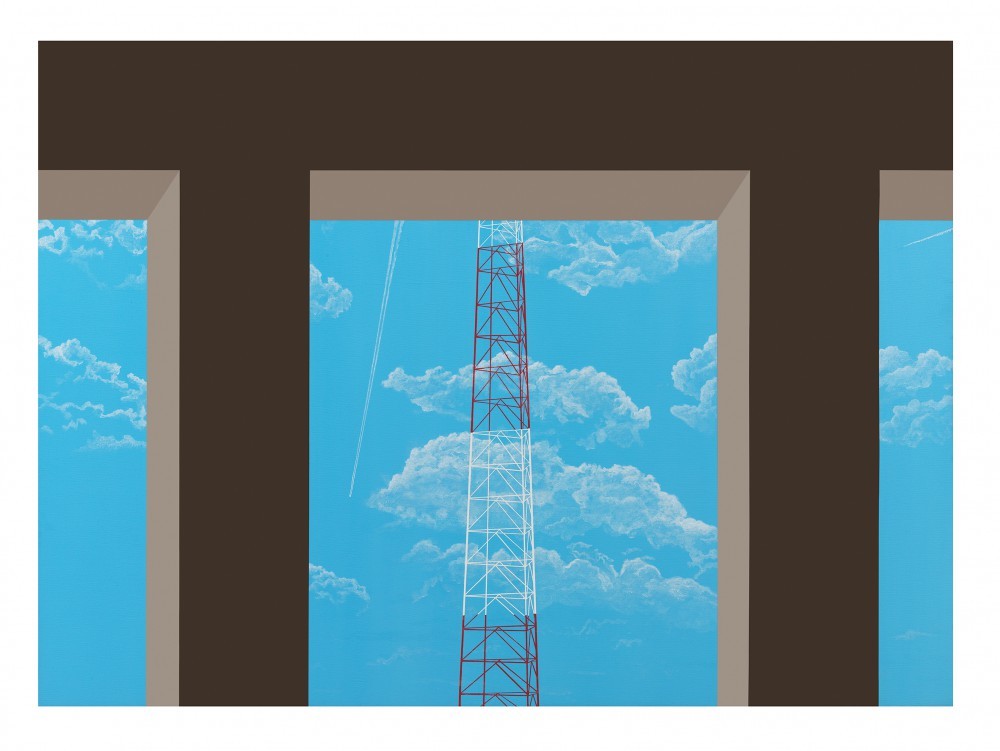

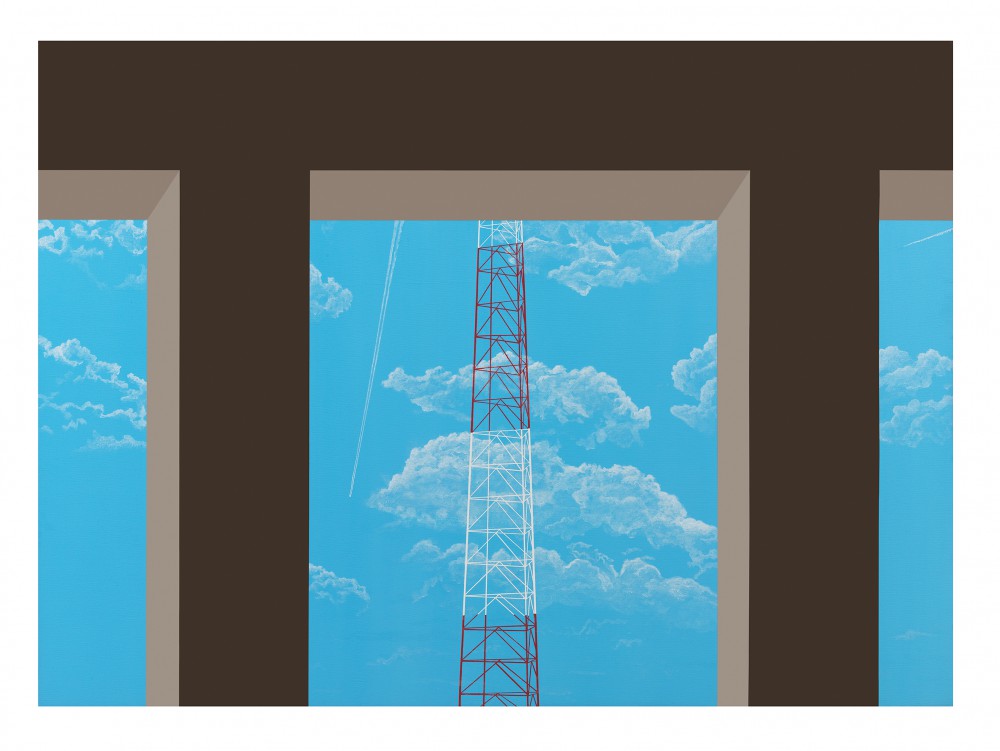

There’s some infrastructural bondage lurking in these paintings, too, whose scaleless scenes recall the delirious new world order and post-apocalyptic utopia of Superstudio’s Continuous Moment. Bordering Without Sound Two is the exhibition’s namesake painting, Pi in the Sky (1981–82), which depicts a highly detailed but cartoonish candy-cane striped radio tower flanked by a similar pair of looming freeway columns in a cheeky composition that takes after the mathematical symbol. Rail and Bridge (1977) casts its lofty overlord in a slightly more gloomy light, with its polluted grey sky and snaking fence cultivating an existential dread unfortunately reminiscent of commuting the 405.

Meanwhile, D’Arcangelo’s Cave (1974), Hypostasis (1974), and Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird (1974) can be read as triplets, both formally and in their shared year of completion. Simultaneously recalling a game, a grid, and the unsightly space invasion of exposed wires and tubes, the entangled telecommunication materials are a quintessentially American endeavor; an aesthetics of more-or-less permanent construction characterizing much of the highway system today.

Installation view of Cave, 1974, at Waddington Custot, London.

While no humans ever enter D’Arcangelo’s strange world, Mr and Mrs Moby Dick (1974) offers an anthropomorphic pair of bulky shipping containers in the back room of the gallery, thrusting side-by-side into the painting’s unknown field. Dressed in white, orange, and black, with another rich purple background, the floating figures have been plucked from whatever surrounds D’Arcangelo first made their acquaintance. Spending some time with the work softens its blunt, almost brutal first impression, as Schwabsky notes, but the strong-willed couple aren’t giving away any secrets; their refusal to make sense of themselves transforms the painting’s immediate harshness into an unforgettable slow burn that comes along for the ride.

In addition to the nautical couple, the back room offers an intimate encounter with D’Arcangelo’s more manageably sized drawings. The cross iconography of Ninosum has a second stand, still no less dramatic in graphite. D’Arcangelo’s fixation with this symbol hits a strikingly contemporary cord with my own visual inventory of the Deep South following a recent road trip from Florida to Texas. Scattered across this swampland is a proliferation of DIY crosses — lingering between art installation and advertisement, some up to four stories tall — most often constructed from wood and painted a blinding white.

Installation view of Allan D’Arcangelo’s Rail and Bridge, 1977, at Waddington Custot, London.

Puncturing the landscape at seemingly random intervals and rooted within strips of in-between land neither public nor private, this invasive religious species captured by D’Arcangelo a half century prior seems the perfect metaphor for the mixed messages of hope and entrapment that continue to characterize America’s sprawling infrastructure space some fifty years on. Like these anonymously planted religious icons, D’Arcangelo’s ambiguous renderings of an off-modern Americana find their perfect match in the beguiling split personality of our complicated political present. Neither here nor there, their vigorous unknowability is a testament to this blank spot on the map of America’s imperfect future, and to the odd prickle of hope still tucked within its folds.

Text by Alice Bucknell. All Images Courtesy the Estate of Allan D'Arcangelo, licensed by VAGA and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York.

Pi in the Sky will be on view at Waddington Custot until February 28, 2018.