ROBIN MIDDLETON’S REMARKABLE EAST VILLAGE HAVEN FOR BOOKS

A part of architecture’s most vital memory lives in the East Village near Stuyvesant Town. A gruff steel door blocks passage, one of several variously sized openings blinded by shades, gates, bars, or murky glass-block, all suggesting that fascinating arcana is to be found within, as does the arresting pitch-black shroud of a façade. This is the home of Robin Middleton. To step across the threshold is to enter a magically erudite sanctum set at an oblique to everyday life. It’s not unlike watching a film by the incomparable Derek Jarman, who, like Middleton in some ways, ministered to London’s cultural scene in the 1970s. Distinguished architectural historian, former editor of Architectural Design (1964–72), former director of general studies and evening lectures at London’s Architectural Association (1972–87), Professor Emeritus of Columbia University’s department of art history and archaeology, Robin Middleton is first and foremost an assiduous time traveler. Not unlike the character of Elizabeth I in Jarman’s Jubilee, Middleton explores patrician history against the grain, locating a spark of modernity in the dustiest of narratives (Elizabeth teleports to a Glam-Punk London of the future oppressed by a police state and terrorized by all-girl vigilante gangs). In a lecture on the prolific Karl Friedrich Schinkel, for example, Middleton could draw a pregnant comparison between 1980s New York gay club The Saint and the German architect’s 1815 stage-set designs for The Magic Flute.

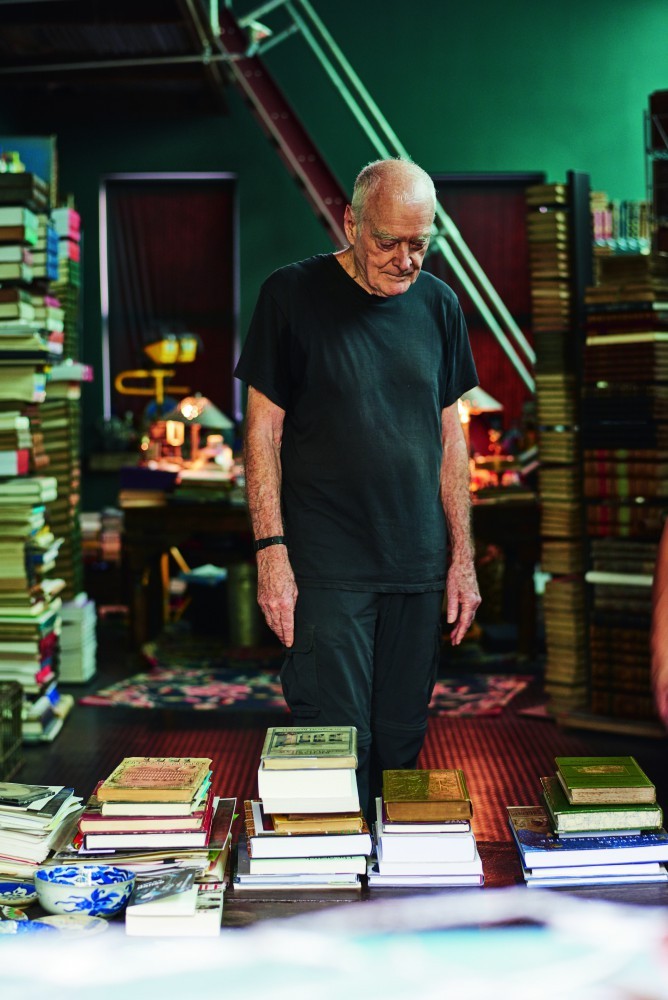

Robin Middleton stands at the top of a staircase in his East Village home. The two-story space has a colorful history as a tile factory and later a marionette theater before Middleton, a noted scholar of architectural history, took it over in the early 2000s.

Born in 1931, Middleton, who initially trained as an architect in his native South Africa, is celebrated for his rigorous arguments and groundbreaking scholarship in the history of architecture in 18th- and 19th-century France and Britain. Few questioned the simplistic opposition of the Gothic and Classical traditions, between Dionysian and Apollonian designs, until Middleton’s work on French theoretician the Abbé de Cordemoy (1655–1714) introduced the notion of the “Greco-Gothic ideal” in 1962 — a wonderfully trans-historical curio of a concept, like so many of the trinkets that populate Middleton’s stationary caravan of a home. His life-long collecting habit equates to the “English vicarage tradition” of nesting with souvenirs from faraway places, the same practice that stocked the British Museum, Middleton observes. Akin to these finely harvested knickknacks, anecdotes pepper his conversation, episodes in architecture’s precious oral history — tea with Buckminster Fuller at the Ritz, the unlikely origin of Kenneth Frampton’s ubiquitous Modern Architecture, or evaluating Zaha Hadid’s term papers at the AA, to name a few.

Middleton’s lifelong habit of collecting trinkets—whether purchased at a neighborhood dollar store or a street stall in Yemen — equates to the English vicarage tradition of nesting with souvenirs from faraway places.

Every corner of Middleton’s home tells a layered story. A fire extinguisher captures the eye, sitting on a thick, hacked-at wood tread leading to the cellar. A photograph shot and hung in the same location shows the bright-red canister next to a precious stack of paper, now gone. Accumulated in that spot for years, the incidental manuscript accounted for weekly visits to a psychiatrist. The extinguisher and the photo commemorate the mind of artist and poet Ruth Lakofski, one of Middleton’s most oft-mentioned life partners, whose apartment and studio were on the first floor of this home.

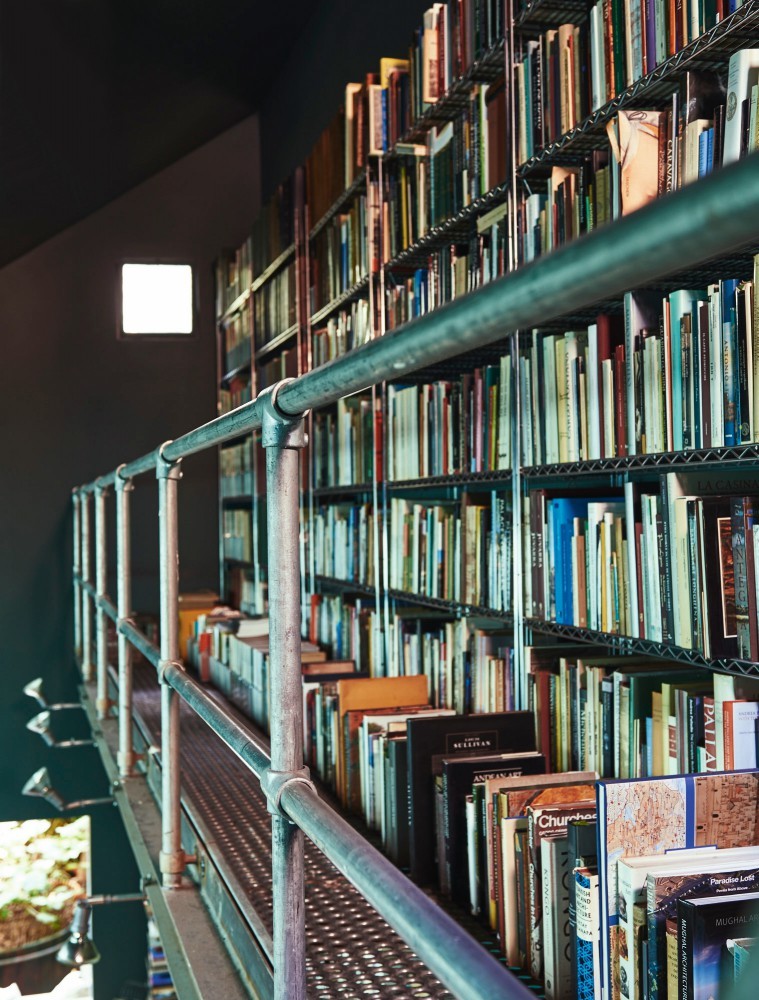

The handrail of thick steel piping and chain link fence is a reference to Frank Gehry’s Santa Monica Residence (1978), as well as to a neighborhood playground in the East Village.

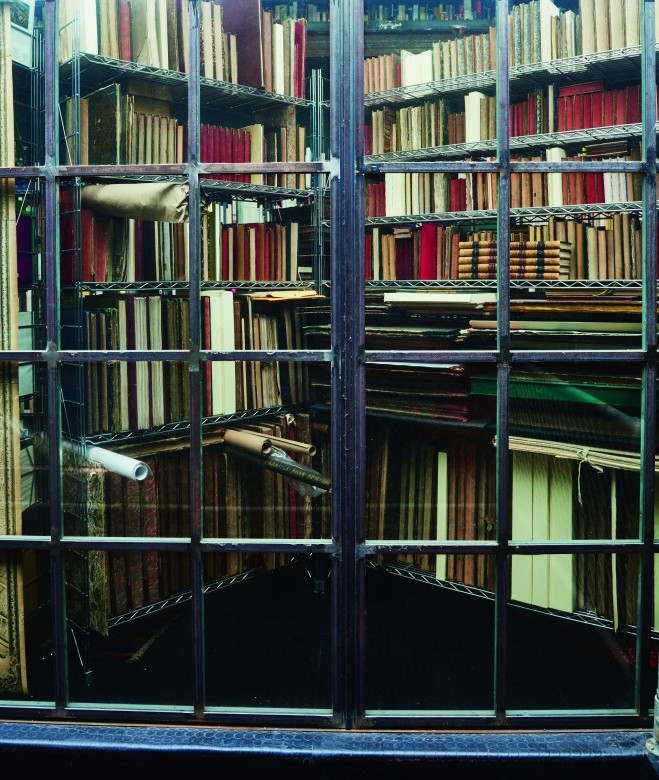

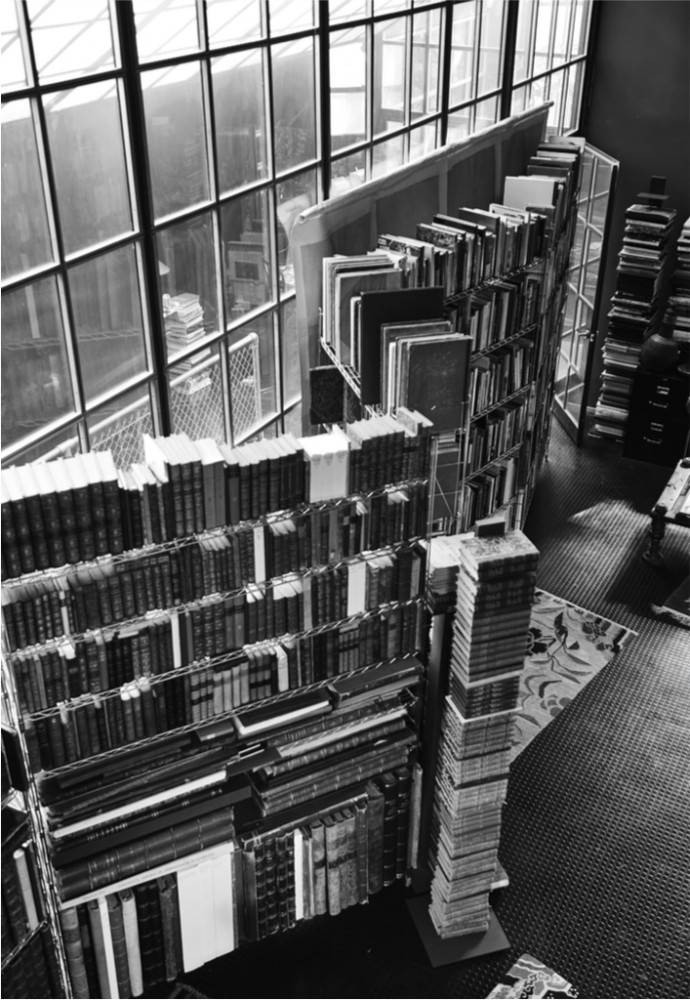

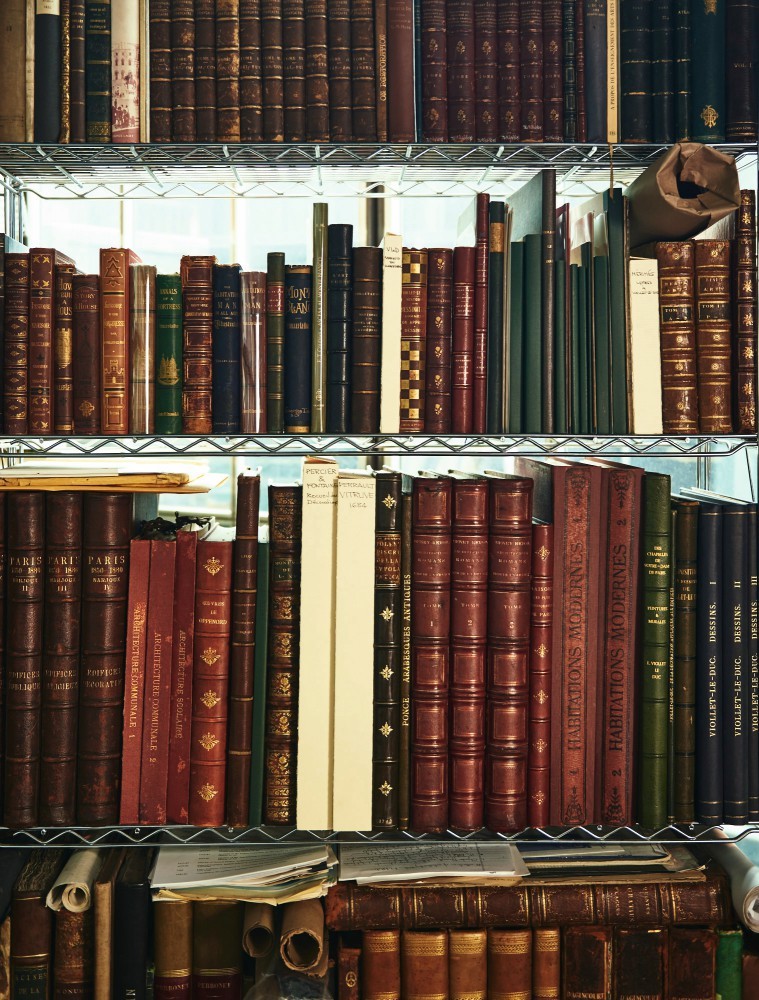

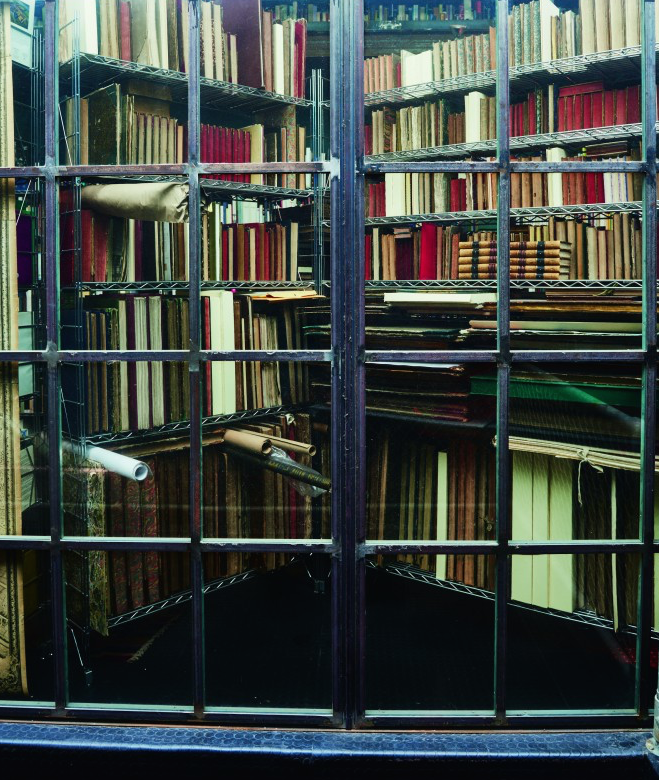

At the opposite end of the space, another flight of rough-hewn stairs continues up into Middleton’s domain. His two-story piano nobile terminates in the glass prism of a conservatory whose diagonal wall records the historic path of the road through Peter Stuyvesant’s farm, the 17th-century property on which this house now stands. Middleton duplicated the angle to set the pitch of the roof — in this home, every detail commemorates another time, another place, things that matter. But design memory comes especially to a head in Middleton’s prized library, kept behind a glass wall that appears to fold down from the skylight, a material metaphor for enlightenment.

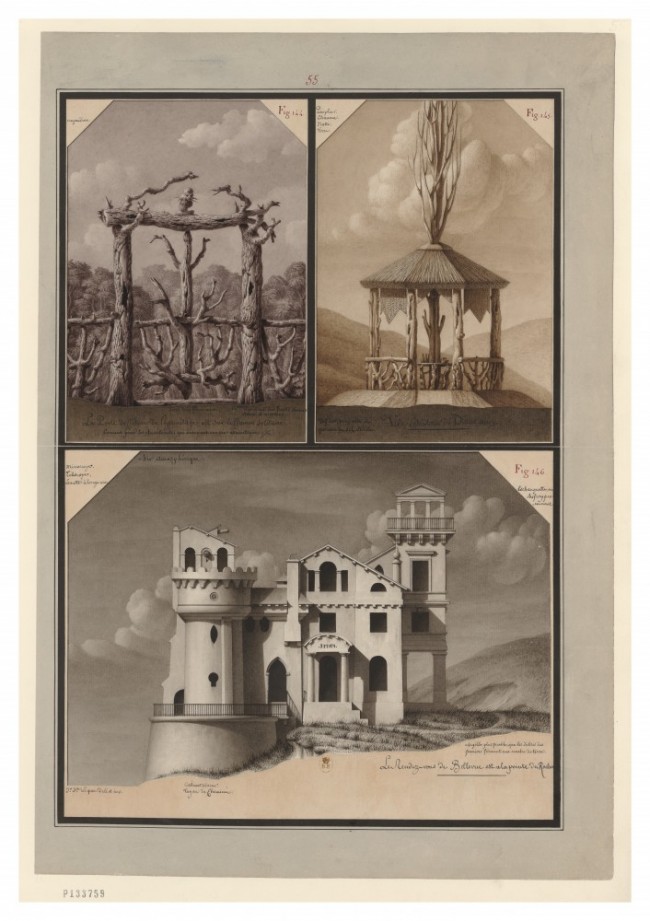

Middleton’s vast personal library contains texts that date back as far as the 18th century, including a few that informed his ph.D. dissertation on Eugène Viollet-le-duc. Middleton also had unprecedented access to Viollet-le-duc’s archive thanks to a serendipitous encounter with the revered 19th-century french architect’s great granddaughter.

Starting with Middleton’s Ph.D. on Viollet-le-Duc, the library amasses evidence of years of study — priceless editions of 18th- and 19th-century treatises, highlights from the Modernist canon, contemporary periodicals, works on geography, travelogues, and general historical texts. Middleton’s collection fills two walls and a loft mezzanine, spilling over into new totem stacks. Sitting behind a heavy wooden desk on a leather swivel chair pinched from his faculty office, Middleton can survey the wide book-lined isle framing a view of the overgrown conservatory, the whole bathed in the greenish hue of daylight bouncing off moss-colored walls and descending through the jade glass of the skylight.

The house’s glass-encased winter garden features prismatic walls that the original street grid of 17th-century dutch colonial New Amsterdam. As a result, the property line of Middleton’s backyard is an extension of Stuyvesant Street, cutting diagonally through what is now known as New York’s East Village.

An unbridled obsession, books, like plant life, naturally make their way all over the house. Unusual gems such as Robert M. Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and an amateur novel by architect Alison Smithson stay on the first floor, along with other literature like Camus, whose tight mercurial prose Middleton greatly appreciates. Of his favorite tomes he shows me two massive folios, one by engraver Jean-Pierre Houël of his late 1770s voyage to Sicily, Lipari, and Malta, and the other by Piranesi. They immediately strike me as another generation’s wide-screen television, so vast and magnetic are the images. Flipping through the heavy, gilt-edged pages seems to slow down time. The fantastic landscapes within begin to shimmer and move, and suddenly the dusty, free, off-road path of Middleton’s life snaps into focus as a perfect extension, a vanishing point to any number of these endless perspectives in print.

Text by Pierre Alexandre de Looz. Photography by Adrian Gaut.

Taken from PIN–UP 21, Fall Winter 2016/17.