INTERVIEW: Architect Julien de Smedt on the Value of the Unbuilt

Brussels-based architect Julien De Smedt founded his eponymous architecture firm Julien De Smedt Architects (JDSA in short) in 2006. Since then he and his team of architects have amassed an impressive portfolio of built projects all over the world, from schools to ski ramps, and from hospitals to private villas —not to mention over a dozen conceptual housing projects, whether in Denmark, France, Korea, or in his native Belgium. (He also has a separate design company, Makers with Agendas, together with William Ravn and Wouter Dons.) As any architect will tell you, for every built project there is a plethora that never leaves the drawing board. And yet even these unbuilt projects can be a vital part of any architect’s design process. Which is why, when it was time to publish the first comprehensive monograph celebrating his work (Built Unbuilt, 2017), De Smedt gave equal weight to his noteworthy extant projects, as well as to those that never made it into real life. During a recent visit to New York, De Smedt walked PIN–UP through his work, both built and unbuilt.

Photo: Josep Fonti for PIN–UP.

Your book is collection of all your finished projects, including some of those that you worked on together during your time at PLOT (2001–06), with your then-partner Bjarke Ingels. What prompted you to also want to show the many unbuilt projects throughout your career? I found it quite daring to expose the underbelly of your practice.

In one’s practice there are always a lot of connections between the various built and unbuilt projects, but those who see the finished buildings don’t necessarily know this. So I felt like it was a good time to just put it all out there, because some of the unbuilt projects have just as much value to me as the finished ones, if not more.

As I was reading it the essay in which you describe all the projects that didn’t see the light of day, I felt like it should become mandatory reading for any student of architecture. Reading it had the strange double effect of being demystifying and incredibly encouraging.

Actually, writing it felt a little bit like when I had to choose my thesis at Bartlett. Because it’s a way of looking back at years of work and thinking: “How could I make sense of all that?” And it’s also as a way to turn the page, and to move on to something new.

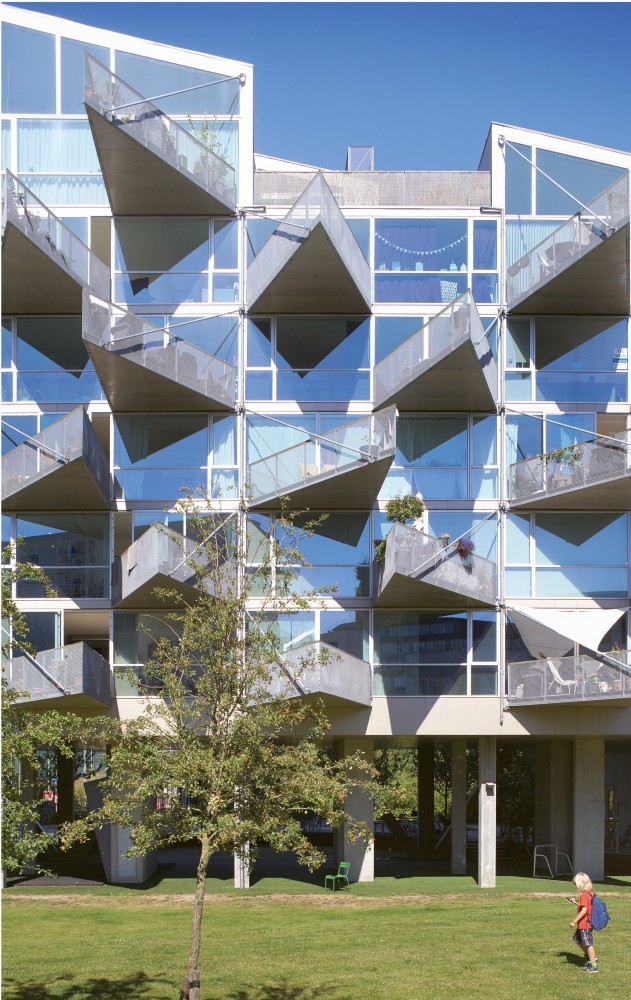

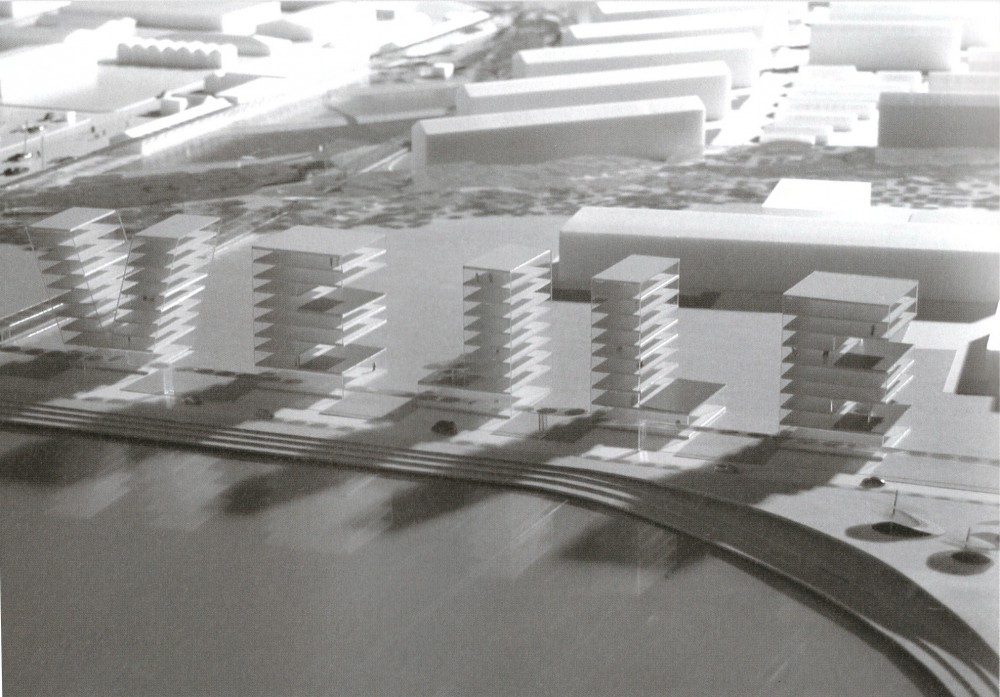

Vejle Harborfront Housing, Vejle, Denmark 2003.

Among those unbuilt projects you describe in the book the one that stood out to me was a series of towers you designed in 2004 for the city of Vejle in Denmark. The project consisted of five apartment towers, which together spelled out the city’s name. Can you tell me more about it?

In 2003 we were working on the entire masterplan of the city’s harbor and as part of it we had proposed to make these buildings that would become the image of the city. The buildings would be facing the back of the fjord, and in the distance there’s a bridge going across the fjord connecting Copenhagen to Aarhus, overlooking at the city. You would pass this city on the bridge, or you would fly over it, and still you would have no idea what the city was because it’s a small provincial, somewhat nondescript city. So in order to give it more of a presence we proposed a housing project that would spell out Vejle’s name. We realized while drawing it that it was actually a very simple set of buildings to do. The L was very easy, the E allowed us to provide for two large hanging gardens, and so on. As you can imagine, we ended up not winning the competition.

Did the idea behind the Vejle project recur in any other projects over the years?

Some of the ideas for Vejle we then used for a mixed-use proposal in Oslo in 2006. It consisted of four towers also spelled out the city name from certain vantage points. We did that project without actually having a client, but it turned out to be quite a controversial project at the time. From there the concept became another unbuilt project in Belgium in 2007, which was still typographic but even more abstract, spelling out the letters B and E, for Belgium. It was a gesture of “belgitude” at the time when Belgium was constantly in the news for not having a government for over a year. And from there we stretched the concept even further — maybe even too much — when we got asked to design something for a city in Belgium called Namur. The brief was for a single building and the city officials felt like they needed some kind of landmark. So we proposed to do a building that was a distorted N, for Namur. After that I think the idea was kind of dead. (Laughs.)

Is the DNA from these projects traceable in any of JDSA’s existing buildings?

In some way, our work with letters lives on in a project we did in Paris. It its part of a bigger master plan conceived by OMA (along with FAA/XDGA) to repurpose an 800-meter-long mixed-use structure in Paris’s 19th arrondissement. They invited around 15 different architects to propose solutions on different parts of the space. Our contribution to the project were Ziggurat Housing N4 and The Invader S4, both social housing projects. We had to work around a great number of regulations of the French building code, but eventually we found a shape, a sort of found object that the regulations imposed on us. I realized the façade resembled the work of French street artist Invader, who does these mosaics that look like characters from the Space Invaders video game. So we decided we’d construct the biggest Invader piece ever made. I contacted Invader’s representative, and he okayed it to be the artist’s largest piece to date. So it’s a face and an artwork, but it also is a translation of the idea of using letters to another type of figure.

Casa Jura, Bois d'Amont, France, 2014. Photo: Julien Lanoo.

Another important project in your practice is the Casa Jura (2014) in Bois d’Amont, France, which seems to blend into the surrounding hillside. In the book you detail the years you worked on convincing the authorities to let you build it, which they finally did. Even though it is a relatively small project it seems to have triggered a lot of programming ideas for your other residential projects.

Yes, the Casa Jura was very important for us, the way it explores the potential of nature in harmony with architecture. There are several projects in the book that explore this potential. It’s the way I would like to live myself, too. I would love to have a house where I feel like the boundary between interior and exterior becomes indistinguishable. I grew up spending a lot of time outdoors, in the French countryside. And also when I was skating I was always outside. The more architecture can disappear and extend into nature or the city, the better. We have the same attitude when working in the city, we try to merge the public space with our buildings, so there’s also a thematic there that’s more about blending interior and exterior, public and private, and so on. It’s an important theme for us, and we spend a lot of time trying to convince authorities to allow it.

Built/Unbuilt feels as much a lesson learned from your professional successes as it is from your “failures.” Would you agree?

Of course. You always have to learn from your failures. As an architect, failure is 90% of your work. (Laughs.)

And if you were given the chance, would you still build all your unbuilt projects?

There are definitely a few I could still imagine putting out into the world. But you also have to understand that the projects in the book are a selection around 75 projects out of 350. There are also many projects we’ve done that you don’t see in the book that I think were just truly failed attempts. (Laughs.)

Interview by Felix Burrichter. Portraits by Josep Fonti. Built/Unbuilt is available through FRAME.

On Monday, February 12, 2018, Julien De Smedt will be participating in a talk about the book together with the photographer Julien Lanoo and Francis Rambert, director of architectural creation at the Cité de l’Architecture.

For more info click here.