INTO THE BLUE: THE VIBRANT HUES OF VILLA MAJORELLE

“…blue will swallow black like a bell swallows silence… blue contracts, retreats, it is the color of transcendence, leading us away in the pursuit of the infinite.”

— William H. Gass, On Being Blue

We make things blue more than we find them that way. The earth may be blue, but we circulate mostly among browns, grays, reds, yellows, and greens, the colors of terra firma and, traditionally, of building forms and materials: the yellow limestone of Jerusalem, the reddish clay of Marrakesh, the dark-gray granite of Santiago de Compostela, or the black volcanic stone of Mexico City. A blue building is an outlier. It has no place in the discourse of authentic materials. Its color proudly announces itself as something applied. Laying no claims to the earthbound hues of construction, blue conjures the unbuilt — the sea, the skies, the unnatural, the immaterial — and its use often signifies the exotic or the sacred.

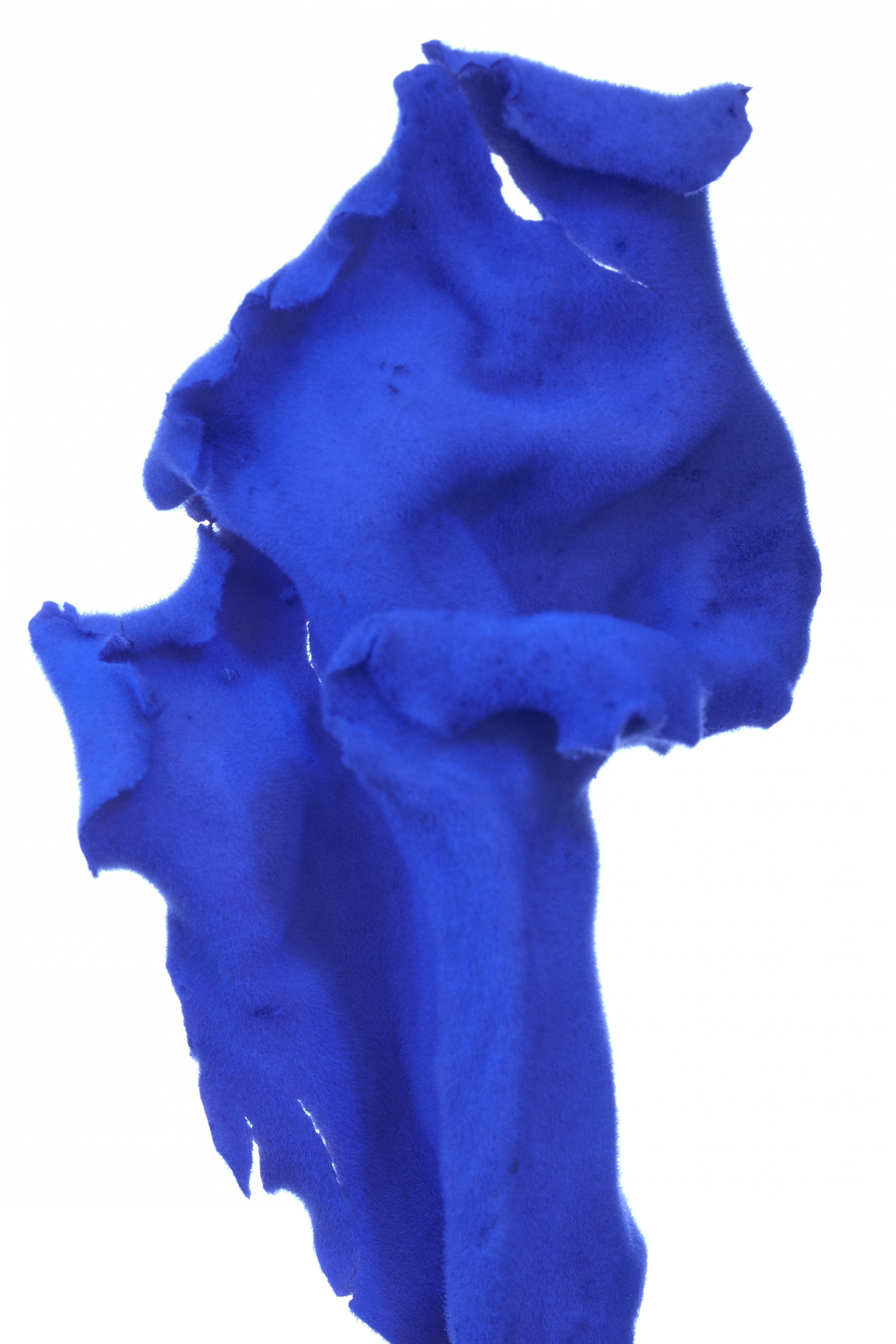

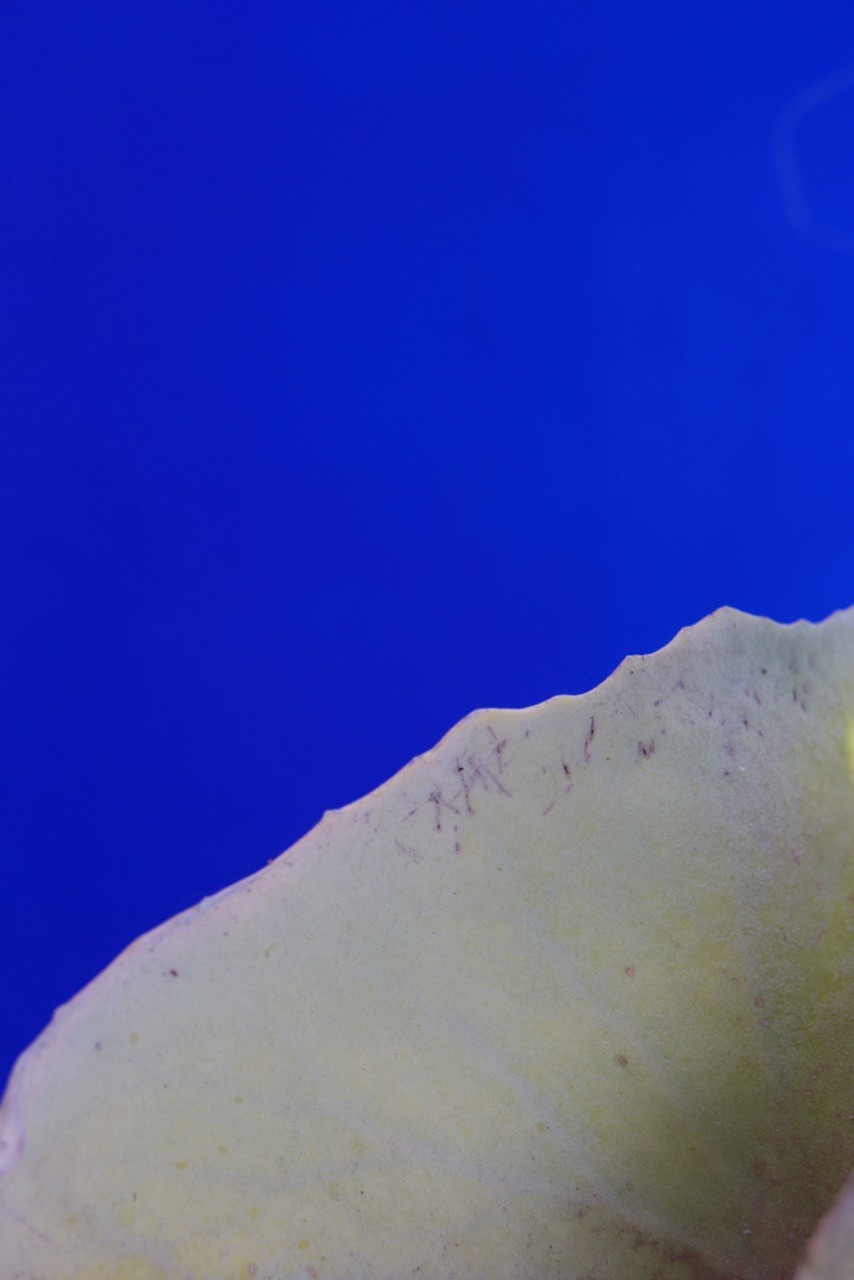

In the 1930s Jacques Majorelle, a French painter living in colonial Marrakech, chose blue as the dominant color for his most significant work, the Villa Majorelle and its famous garden. This twelve-acre property comprises a diverse collection of exotic plants set against the rich blue walls of Majorelle’s home and studio. In part, he drew inspiration from the Sahara’s nomadic Tuareg people, whose deep-blue robes and veils signified wealth and were also meant to ward off evil spirits, earning them the moniker “blue people of the desert.” Majorelle Blue, as it came to be known, was not intended as talismanic, and though it evoked the exotic, it achieved more than that at the villa. Applied to the rough stucco walls, the blue itself becomes spatial, creating depth, a blue void that retreats from the viewer and hints at the infinite, elevating the Villa Majorelle into a sanctuary amid the pink clay stucco of Marrakech. After falling into disrepair following Majorelle’s death in 1962, the property was purchased in 1980 by Yves Saint Laurent and his partner Pierre Bergé, who restored and permanently opened it to the public.

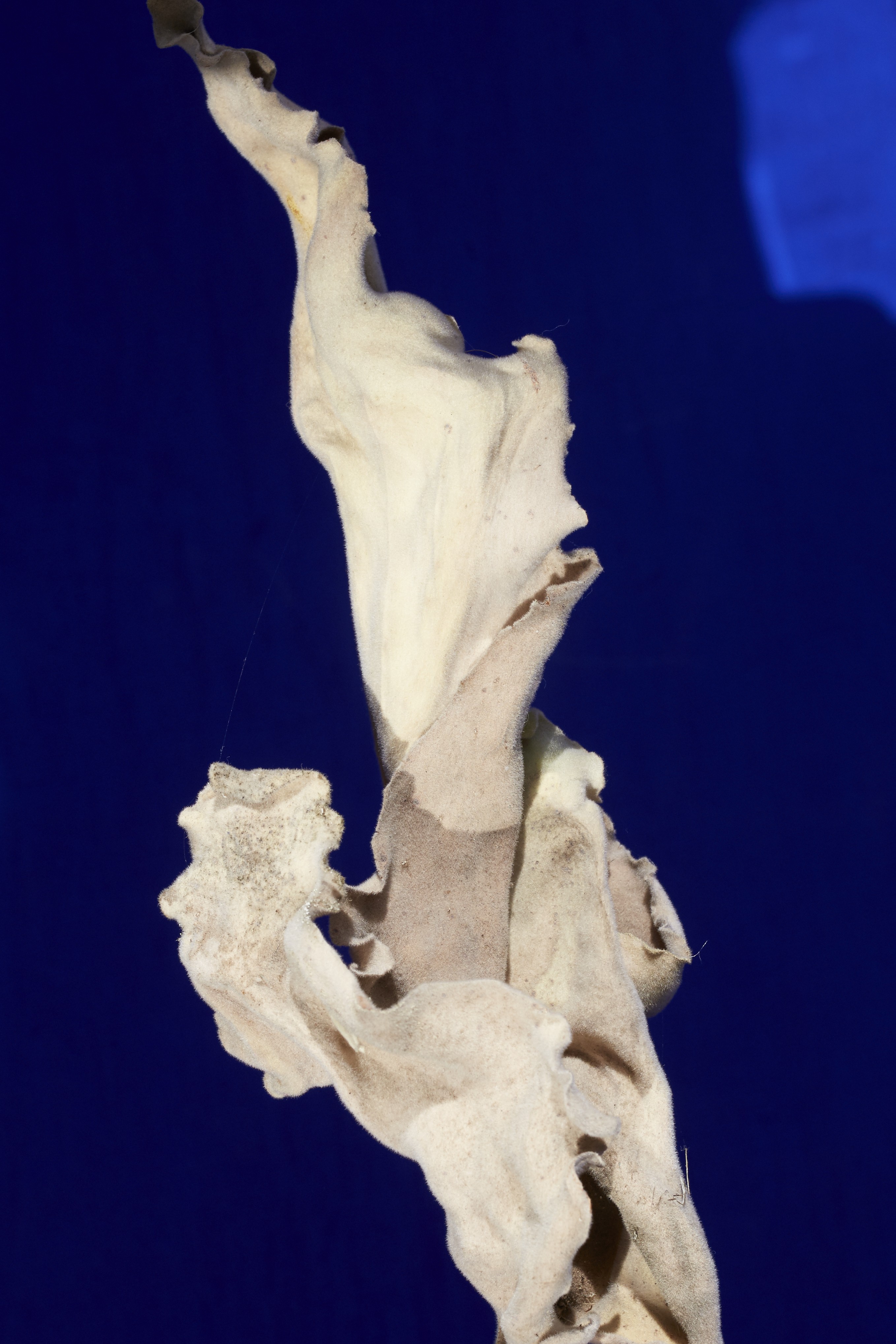

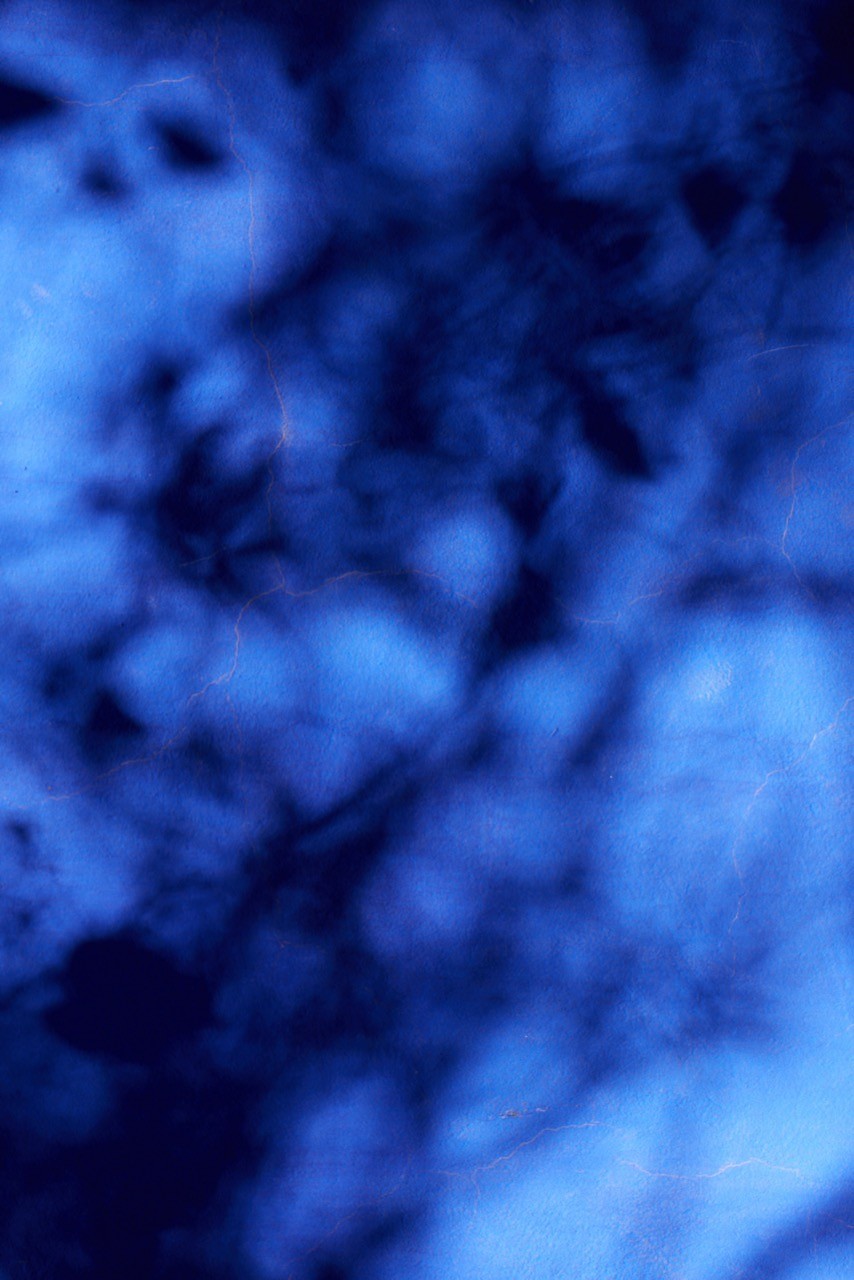

Four hundred miles north of this blue garden, in the thin air of the Rif Mountains, is the town of Chefchaouen, located in a region known for its prolific cannabis production. The buildings within the town’s medieval walls are painted white and blue. Their rounded contours scatter a blue-tinged light throughout the steep, narrow alleyways, blurring the distinctions between volumes and surfaces. It appears, at times, as though the blue structures might evaporate and merge with the sky. Founded in 1471 as a base to combat the invading Portuguese, Chefchaouen grew at the turn of the 16th century with an influx of Jews and Muslims fleeing the Spanish Inquisition. In Jewish tradition, blue is the color of divinity (a single blue thread in the fringe of a prayer shawl reminds the worshipper to fulfill the commandments), and it is Spanish Sephardi Jews who are believed to have turned Chefchaouen blue. But in some Islamic cultures blue is thought to ward off the evil eye and is consequently used to paint front doors. Quite how this mutual belief in the powers of blue became an urban color strategy remains unclear.

The chalky, fragile, celestial hues of Chefchaouen bear only a faint resemblance to the intense shade of the Villa Majorelle, but both refuse a submission of color to form. Rather than merely decorate, they spatialize surfaces and dematerialize place, bearing testament to that strange otherworldliness of blue.

Taken fromPIN–UP 18, Spring Summer 2015.

Photography by Johann Clausen with Daniel Sannwald.