MEAT MARKET MEMORIES: Paul Haacke on Growing Up Alongside the Hudson River Piers

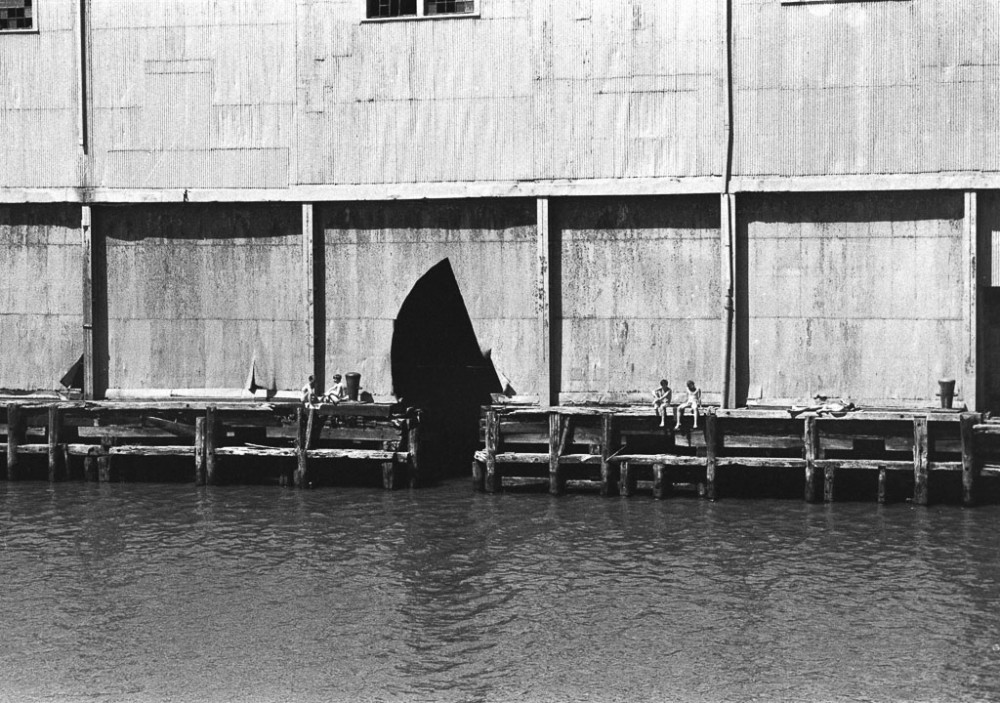

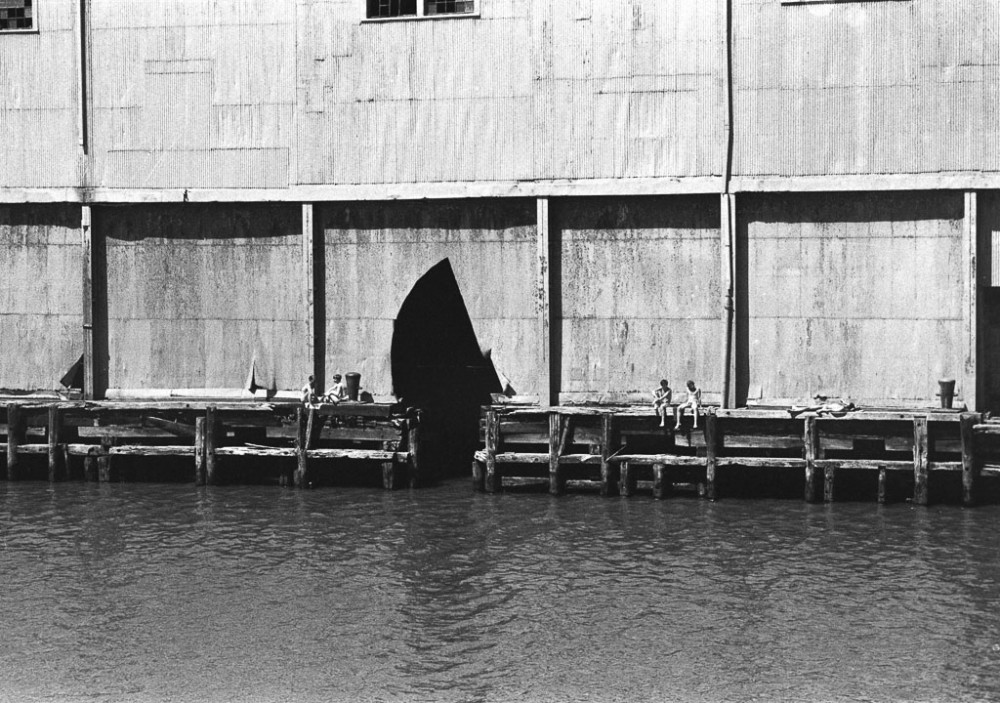

Gordon Matta-Clark’s Day’s End (Pier 52) in 1975. Photograph use courtesy of The Alvin Baltrop Trust, © 2010, Third Streaming, NY, and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York, all rights reserved.

The giant steel columns holding up the elevated High Line promenade in Lower Manhattan are the final nails in the coffin of the once crude Meatpacking District and the queer no-man’s-land that was the Hudson River waterfront. I grew up in that neighborhood during the Reagan-Bush years, and still, every time I return, I’m shocked by how much it’s changed. Always a far cry from the quaint West Village characterized by Jane Jacobs in her 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, this area saw the rise of late-night sex clubs, prostitution, cruising, the drug wars, the AIDS crisis, and trickle-down economic recession. It was only much later that the area eventually gave way to gentrification, yuppification, guppification, and the influx of commercial enterprises. I must admit, I’ve had mixed feelings about all of it. Sure, the neighborhood is safer, cleaner, and more open now, but it’s also become standardized, pretentious, and over-priced. In the old days, the transgender hookers used to smile at you when they walked by in the street, whereas today the trend-seeking tourists and fashion models turn up their noses with an icy air of entitlement. Or is this just my childhood nostalgia talking?

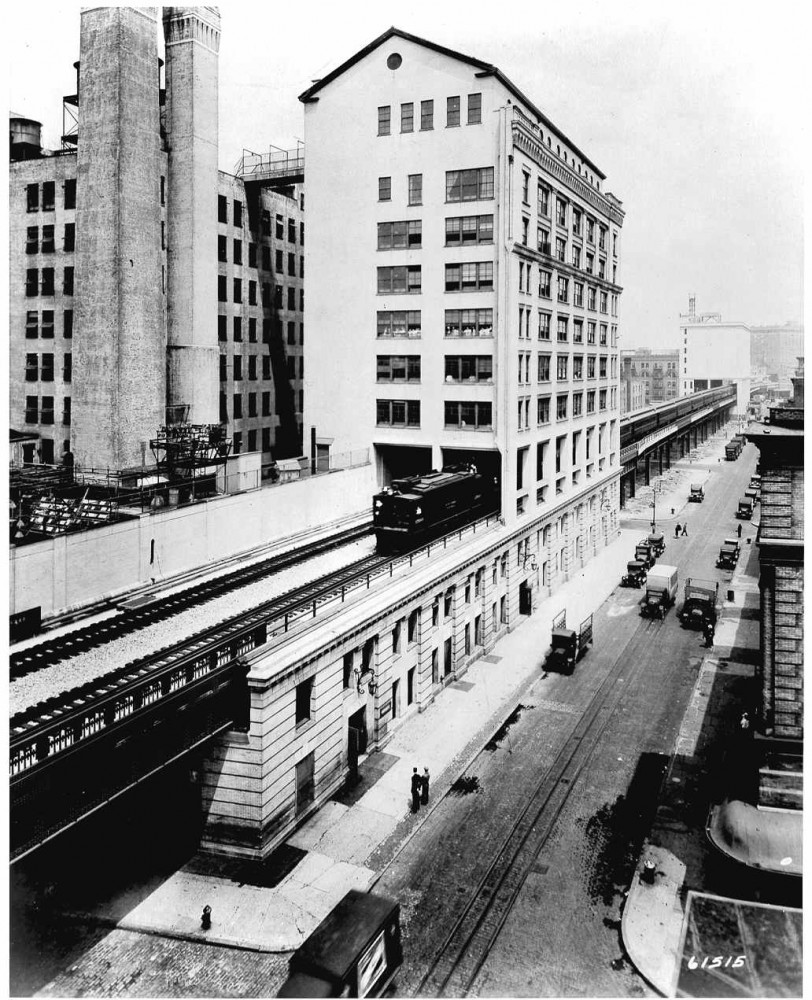

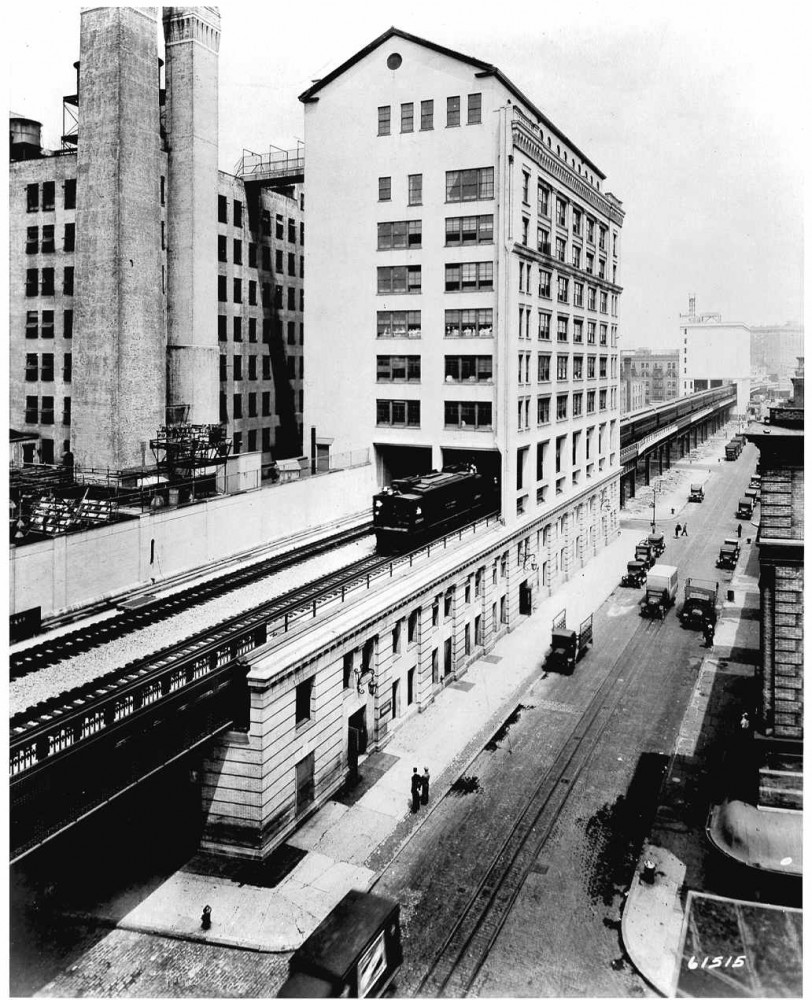

The High Line tracks going through the Bell Telephone Laboratories Complex (now Westbeth Artists' Housing building) in 1936. Photograph copyright National Geographic.

Westbeth, the historic building in which I grew up, also came of age during this period as an unprecedented, rent-subsidized housing project devoted exclusively to artists and their families. Taking up an entire city block at the corner of West and Bethune and rising 13 stories, the massive edifice was completed in 1898 as an industrial-research lab for the conglomeration of Western Electric, AT&T, and Bell Telephone. Apparently, a great number of technologies besides the telephone were also developed there, including phonograph recording, talking pictures, television, radar, and the vacuum tube. During World War II, it even served as a research facility for the Manhattan Project. When Bell moved out in the mid 1960s, the building was purchased by the newly founded non-profit Westbeth Inc. (with financial support from the National Council on the Arts and the J.M. Kaplan Fund) to provide affordable housing for artists struggling to develop their careers in the city. Debuting architect Richard Meier was commissioned to transform the giant labyrinth of empty offices and labs into nearly 400 residential apartments and work spaces for artists of all disciplines, including painters, sculptors, writers, musicians, dancers, and actors. Westbeth opened to tenants in 1971, and now also includes a gallery, a theater and drama school, a gay-and-lesbian synagogue, the world-renowned Merce Cunningham dance studio, and the relocated Brecht Forum.

A 1976 photograph of the Chelsea piers. © Leonard Fink, courtesy of the National Archive of Lesbian and Gay History.

Before the arrival of the pretty Hudson River Park in 2003, or of luxury condominiums like the glass towers at Perry and Charles (2000–06, also by Meier), our apartment windows looked down onto an abandoned strip of wasteland. This terrain vague is what bridged the once-elevated West Side Highway and the dilapidated piers that jutted out into the river. Aside from folks jogging, fishing, or practicing their musical instruments, it was mostly used for drug dealing, gay cruising, and prostitution. Only a few blocks inland were the brownstones and tenements of the gentrifying, post-Jane Jacobs West Village. Below Bank Street is where the affordable, low-rise West Village Houses were built, now overshadowed by Julian Schnabel’s garish Palazzo Chupi (2008), and further south was the newly emerging TriBeCa. Across Bethune Street was the Superior Ink factory, which occupied the whole block before it was replaced by luxury townhouses and condominium towers. Further up, the proverbial “eyes on the street,” which Jacobs attributed to safe, mixed-use communities, seemed few and far between. The fortress on the corner of Jane and West, originally built in 1908 to house sailors docking for the night, was for decades known as the live-in Hotel Riverview, later renamed the Jane West. The residents of this single room occupancy have since been evicted in order to make room for the trendy new Jane Hotel (owned by the same people who opened the upscale Bowery Hotel right next door to an old halfway house). Finally, one block further up was the seedy Meatpacking District, where the streets were shared by industrial workers and sex workers alike.

It took a couple more decades before boutique (or big-business) clothing stores, restaurants, bars, and hotels started cutting through the grit and grime of the meat market and replacing the steel shutters with plate glass windows. While in 1900 there were about 250 meat plants in operation, by last count there were only twelve, the rest having either closed down or moved to Hunts Point in the Bronx. While most of the area has been designated a historic district, it is also being marketed with a new brand name: “MePa.” It’s a wonder that the late-night diner Hector’s has survived all these years since it first opened in 1949, when the Gansevoort Market Meat Center was just becoming established as a wholesale co-operative of about 120 companies. Despite appearances, the Hogs and Heifers saloon opened much later, in 1992, but even then, it sported a much more raw flavor than it does today.

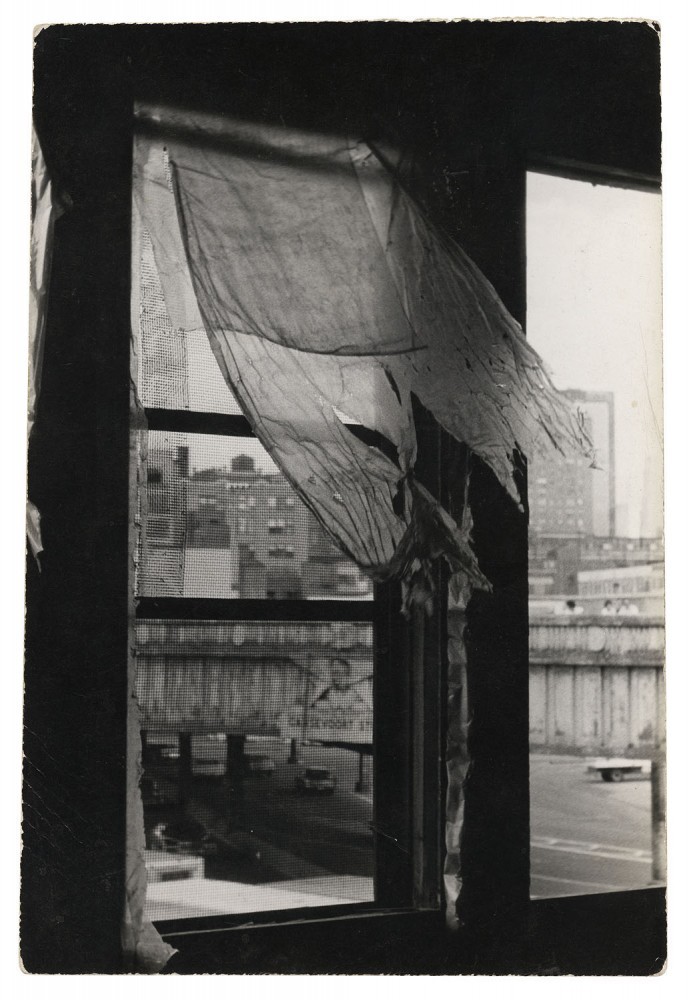

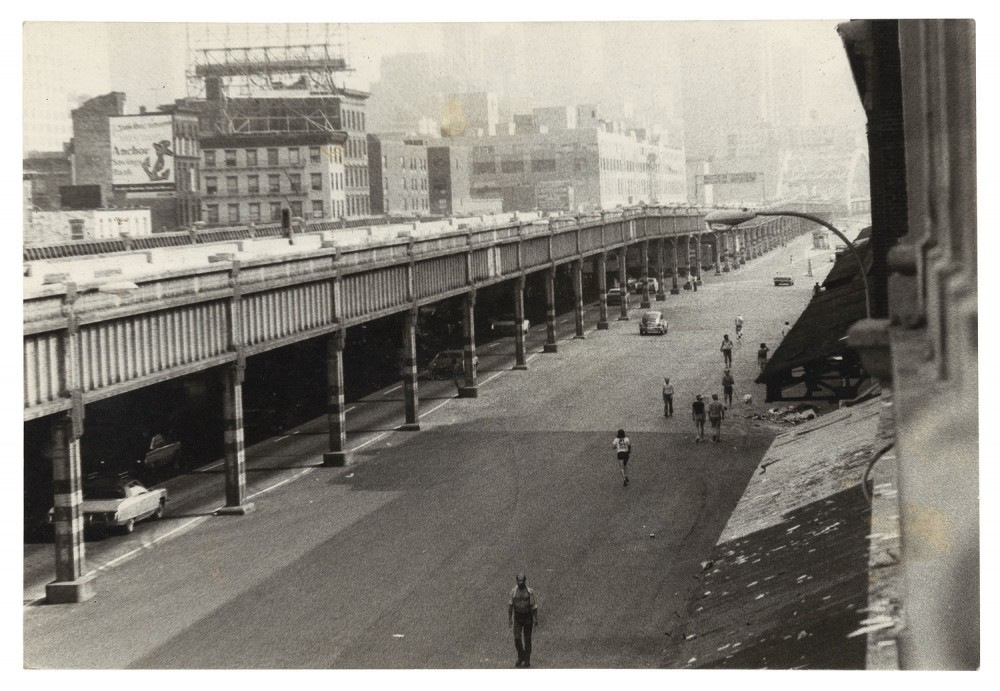

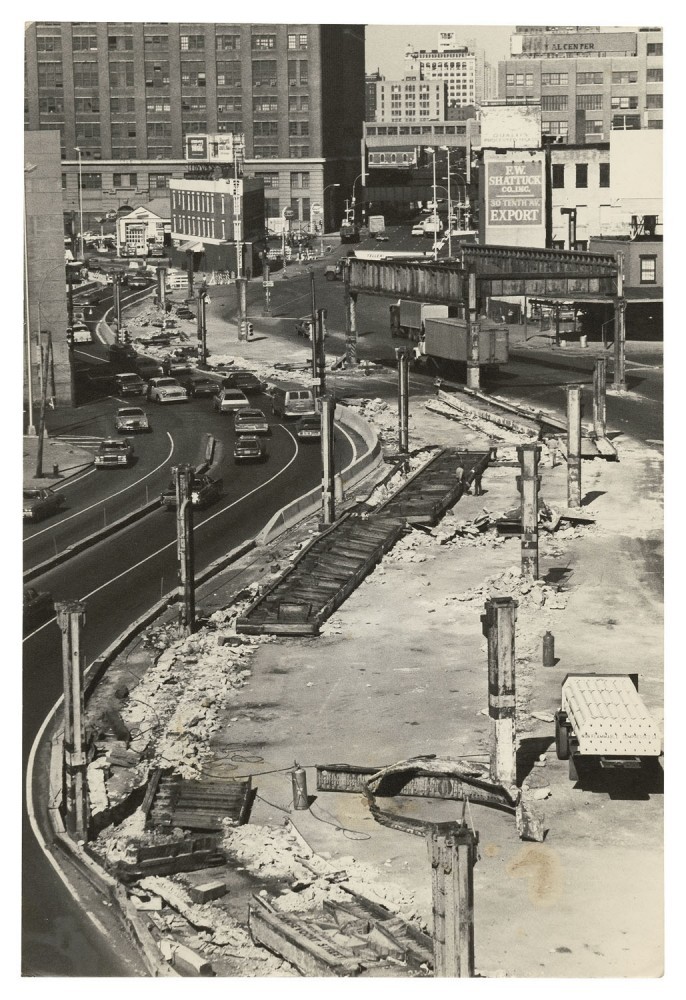

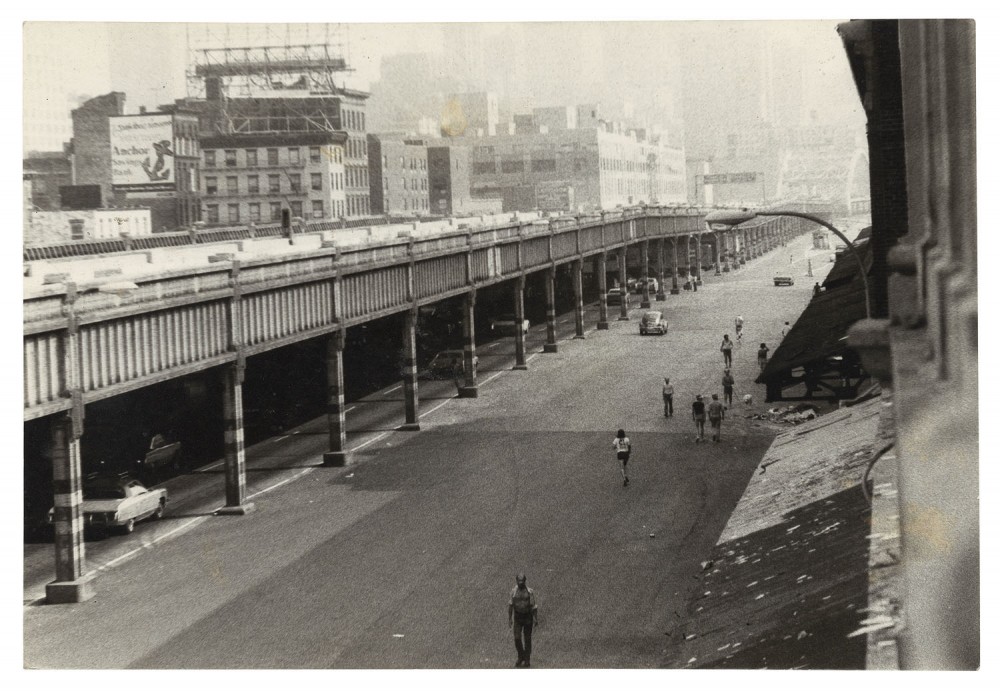

West Side Highway and pier façade, n.d. (1975–86), Photograph use courtesy of The Alvin Baltrop Trust, © 2010, Third Streaming, NY, and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York, all rights reserved.

Arguably the most significant arrival on the scene, however, was the 24-hour bistro Florent, which opened in 1985 when the meat market was still new to bohemians and night owls. Unlike most of the restaurateurs who moved in later, owner and gay-rights activist Florent Morellet embraced the marginality of the neighborhood instead of simply trying to capitalize on its legacy. In the summer of 2008 he too was priced out, and 69 Gansevoort Street has been taken over by a derivative replacement. A tough question now remains for many of the artist types who frequented Florent or settled into Westbeth during this period: did they unwittingly help to pioneer the gentrification that would ultimately alienate so many of them years later? As for the residents of my building, most of them never had much money to splurge on food or fashion, and though some did get into various illegal substances, for the most part this weird housing project always maintained a unique independence from the market forces of drugs, prostitution, and real-estate speculation that, depending on your tastes or income-level, either infested or enlivened the neighborhood.

Running directly through a tunnel in the third floor of my building were the elevated tracks of the High Line, which was originally constructed in the 1930s as a substitute for the dangerous freight railroad that had been built along the waterfront back in 1840. Before the tracks were raised above the ground, horse-mounted “West Side Cowboys” used to warn of arriving trains. But accidents and collisions were apparently so frequent that Eleventh Avenue came to be called “Death Avenue,” and safer means of transportation were sought. By the time the elevated trains were fully discontinued in 1980, the tracks had already been taken over by wildflowers, weeds, teenagers, and homeless people. A bunch of the older kids I knew would hang out or do graffiti or drugs on the overgrown, rusty platform, and a few times I felt pressured to join in. Presumably, all kinds of cruising and hustling took place up there as well, but I wasn’t too aware of that as a kid.

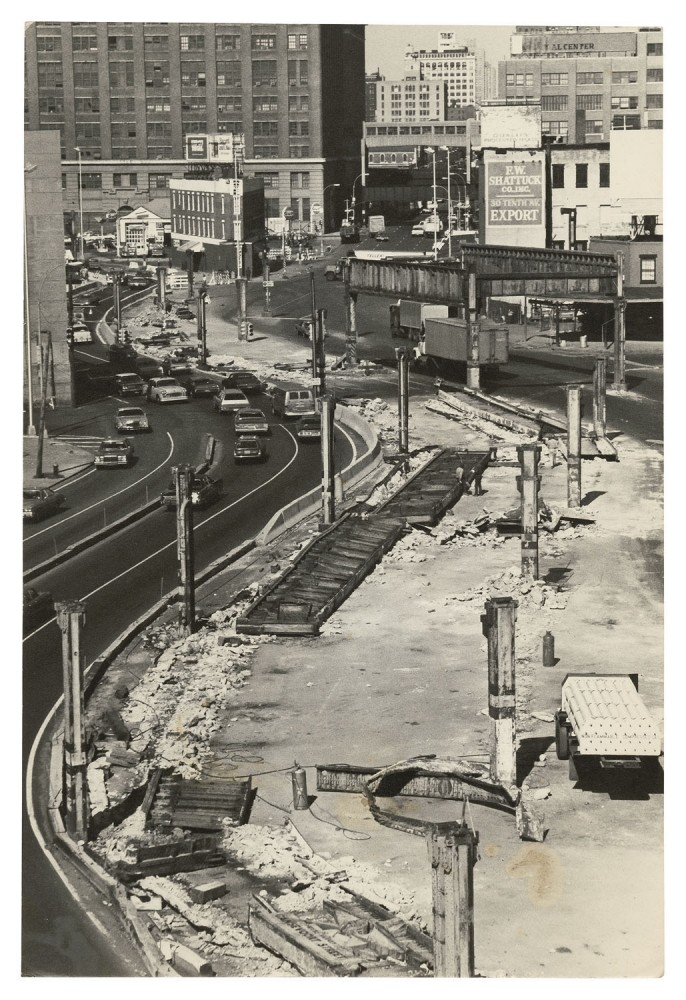

Dismantled elevated West Side Highway, n.d. (1975–86), Photograph use courtesy of The Alvin Baltrop Trust, © 2010, Third Streaming, NY, and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York, all rights reserved.

In the early 1990s, after higher-paying tenants started moving into the neighborhood, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani kicked off plans to demolish the entire structure, but an advocacy group calling itself Friends of the Highline quickly formed to save it. In 1999, organizers Joshua Davis and Robert Hammond — with help from Joel Sternfeld’s beautiful series of photographs, Walking The High Line — finally managed to convince the newly elected mayor, Michael Bloomberg, to transform the abandoned railway into the wonderful pedestrian pathway that it is today.

The new High Line park opened to the public in June 2009, running 30 feet above ground from Gansevoort Street to 20th Street in Chelsea (although the full route extends for a mile-and-a-half all the way up to 34th Street). Inspired in part by the Promenade Plantée atop the Viaduc des Arts in Paris, which opened on a reclaimed elevated railway in 1993, the pedestrian High Line was designed by James Corner Field Operations and architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro. Despite the economic crisis, many expensive buildings have been emerging on either side of it in recent years, most of which flaunt glass curtain walls with skewed angles that pull the eye upward. The one that still seems to be grabbing the most attention from the walkway is the Standard Hotel (2009), designed by Todd Schliemann of Polshek Partnership Architects (renamed Ennead Architects in mid-2010), although it has provoked wildly disparate reviews from critics. It appears to guard over the area like an awkward, retro-chic robot, begging the question: Is it friendly, like R2-D2, or menacing, like something from War of the Worlds?

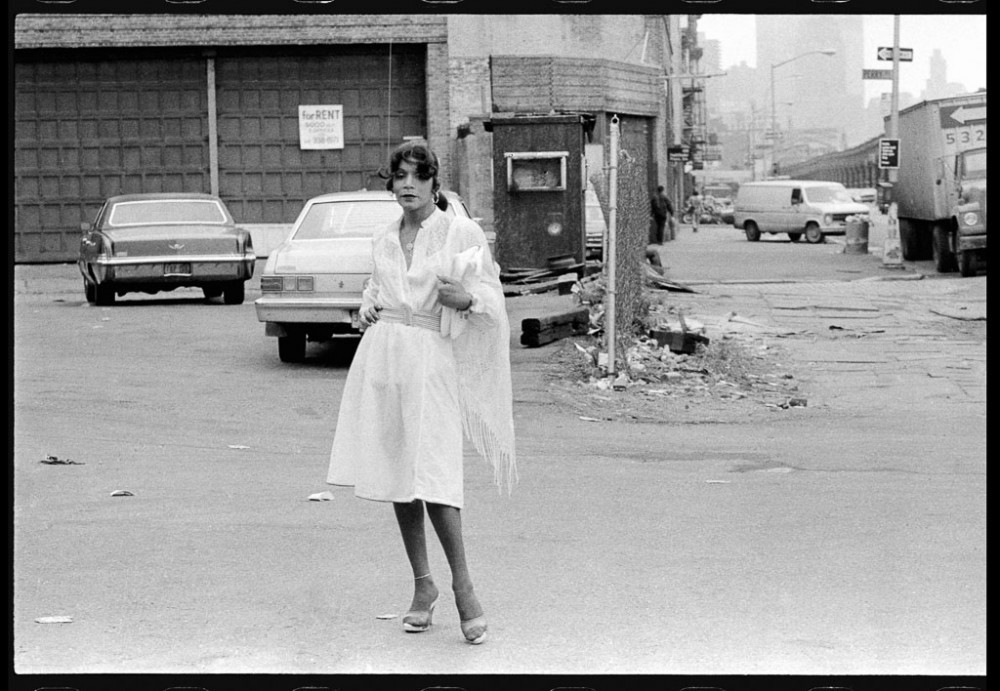

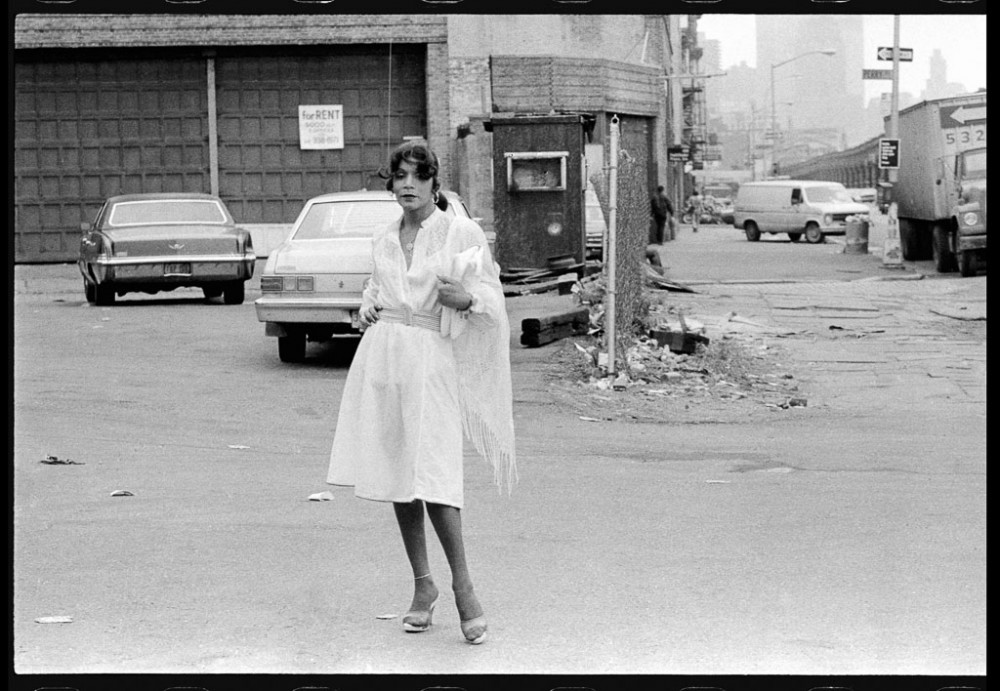

Meatpacking District street scene in the mid-1970s. Photograph use courtesy of The Alvin Baltrop Trust, © 2010, Third Streaming, NY, and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York, all rights reserved.

More widely celebrated is Frank Gehry’s bulbous, frosty IAC headquarters on the corner of 11th Avenue, which was the first major new arrival to the area when it was completed in 2007. Just across from it on 19th Street is Jean Nouvel’s eye-catching, 23-story condo tower (2006–10), clothed in multi-layered, variegated glass panels that shimmer like crystalline snakeskin. Further down the street is Shigeru Ban’s bright, sleek-looking Metal Shutters House (begun 2007), and a few blocks away on 18th Street is Audrey Matlock’s award-winning Chelsea Modern (2009), with rippling, horizontal waves of blue-tinted and clear glass. A little further uptown, in the midst of numerous tenements, brownstones, warehouses, and low-income housing projects, are several other brand-new luxury condominiums: Annabelle Selldorf’s 19-story, faux-industrial residential tower at 200 11th Avenue (begun 2008), which is programmed to include individual garages accessible by elevators from each apartment; Della Valle Bernheimer’s shiny metallic structure at 245 10th Avenue (begun 2007), curving over a gas station; Lindy Roy’s High Line 519 (2007), with rounded, stainless steel scrims that meander up its glass façade; and, right next door, Neil Denari’s HL23 (begun 2008), which cantilevers over the High Line with a “reverse tapering” glass façade that widens as it rises. Planned for the southern end of the elevated walkway is Renzo Piano’s design for the new downtown branch of the Whitney Museum, which promises to steal some of the shine from Gehry’s corporate igloo.

-

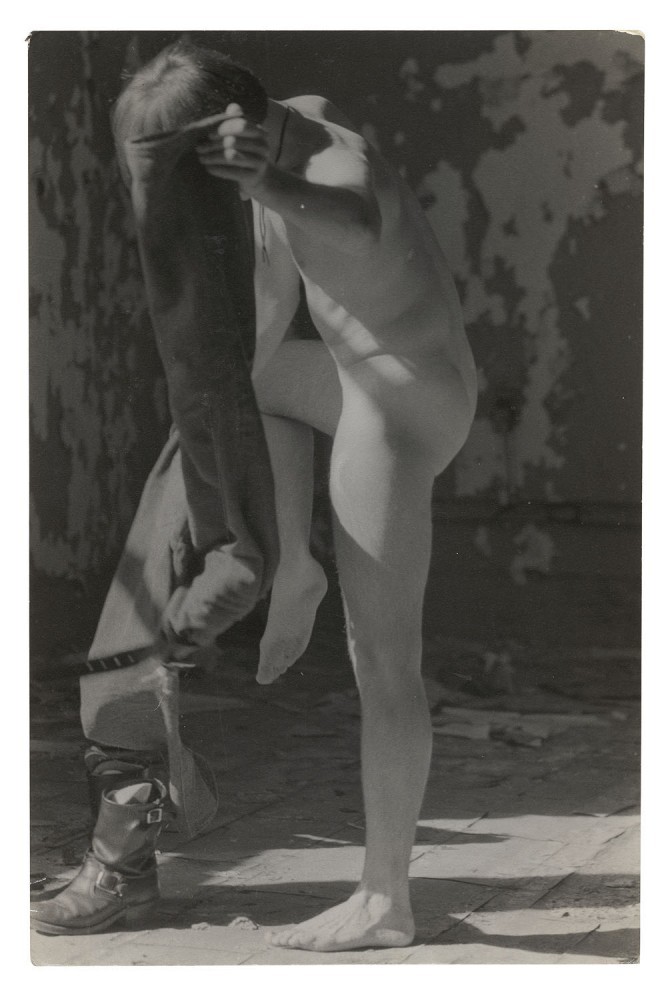

The Piers (two men sitting), n.d. (1975–86), Photograph use courtesy of The Alvin Baltrop Trust, © 2010, Third Streaming, NY, and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York, all rights reserved.

-

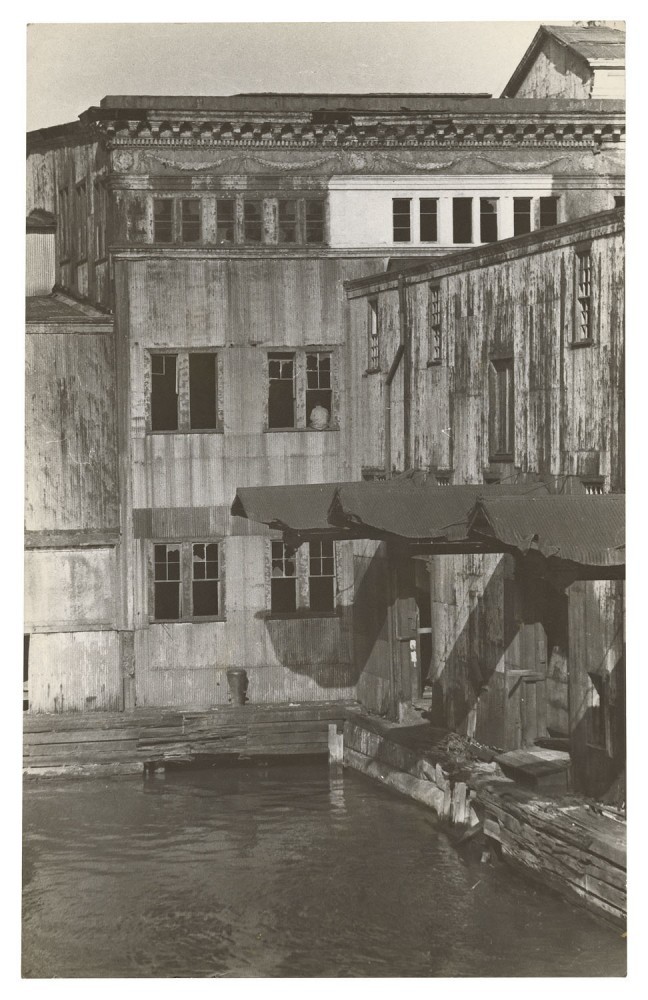

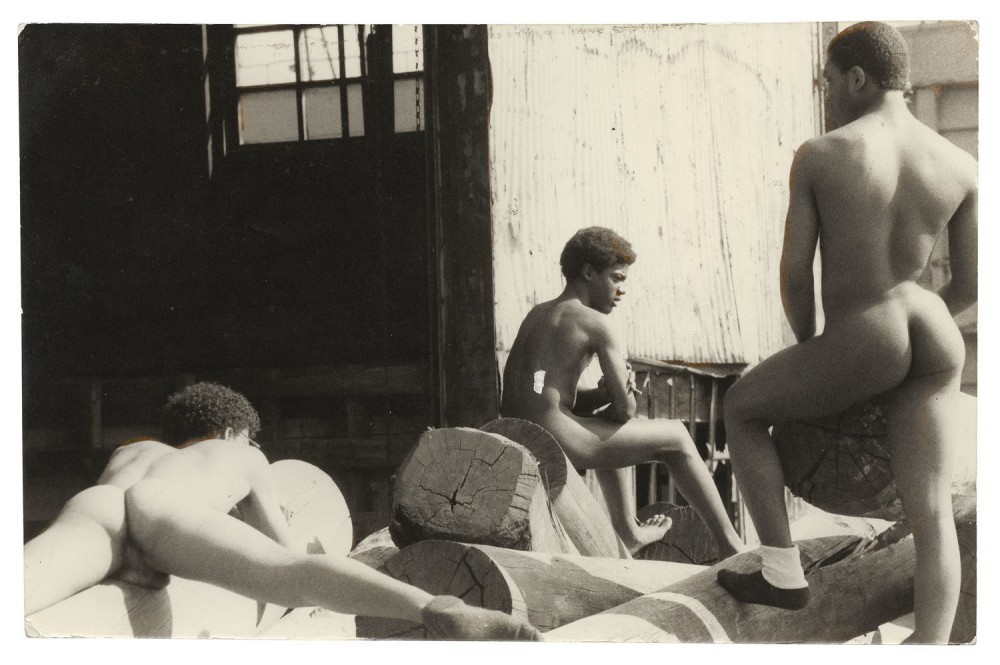

The Piers (three men on dock), n.d. (1975–86), Photograph use courtesy of The Alvin Baltrop Trust, © 2010, Third Streaming, NY, and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York, all rights reserved.

Well before any of this was even imagined, the Meatpacking District of my childhood was still full of wholesale retailers who did indeed wash, display, pack, and sell meat. The streets were pretty smelly and slippery during the day, with dripping carcasses strung up on metal hooks from overhead rafters extending over the sidewalk. At night, however, an altogether different meat market would emerge from the shadows, as partygoers and prostitutes of various ethnicities, sexualities, and genders came out to work and play. As a kid I wasn’t really aware of what happened after dark, but even during the day I saw plenty of people wiggling about in feather boas, colorful bras, and sequined miniskirts, or heard the tell-tale click-clack of high heels traipsing across the cobblestone streets. I usually couldn’t tell if they were men or women, especially as most were a little of both. Sometimes I’d cross paths with hookers on my way to school in the morning. Feeling bemused rather than threatened, I simply avoided eye contact and kept my backpack straps tight in hand. I was confused about who they were and what they were doing, but I avoided thinking about it too much and refrained from asking any embarrassing questions. For a long time I was also oblivious to the many crumpled condoms littering the sidewalks, just as one would rarely think to question how chewing gum gets spit out and stuck there. But after I learned a little about the birds and the bees and understood what those latex droppings actually were, I started speculating, and eventually came up with the naïvely hetero-normative theory that guys would put their used rubbers in their pockets and get rid of them in the street to avoid dirtying their girlfriends’ trash bins. I tried not to ponder why there were sometimes lacy panties lying on the sidewalk too.

For most of my childhood I was ignorant of the more illicit activities that used to take place in the neighborhood and assumed that we lived in a basically “normal” part of downtown Manhattan. Shortly before I hit puberty, however, I started noticing the public ballet of gay cruising that was visible from our tenth-floor window. For my tenth birthday, my parents gave me a little telescope to encourage my newfound interest in astronomy, but I started spying on the activities down below instead. At first, much of my voyeuristic energy was spent on trying to figure out why there were so many cars and limousines circling around under the tall hooked streetlights when the sun went down, or why people kept sauntering up to them or convening along the concrete barriers at the water’s edge. Since hardly anyone got in or out of the cars, most of the action I saw was probably drug-dealing rather than cruising or prostitution, which more often took place under the blanket of darkness on the piers.

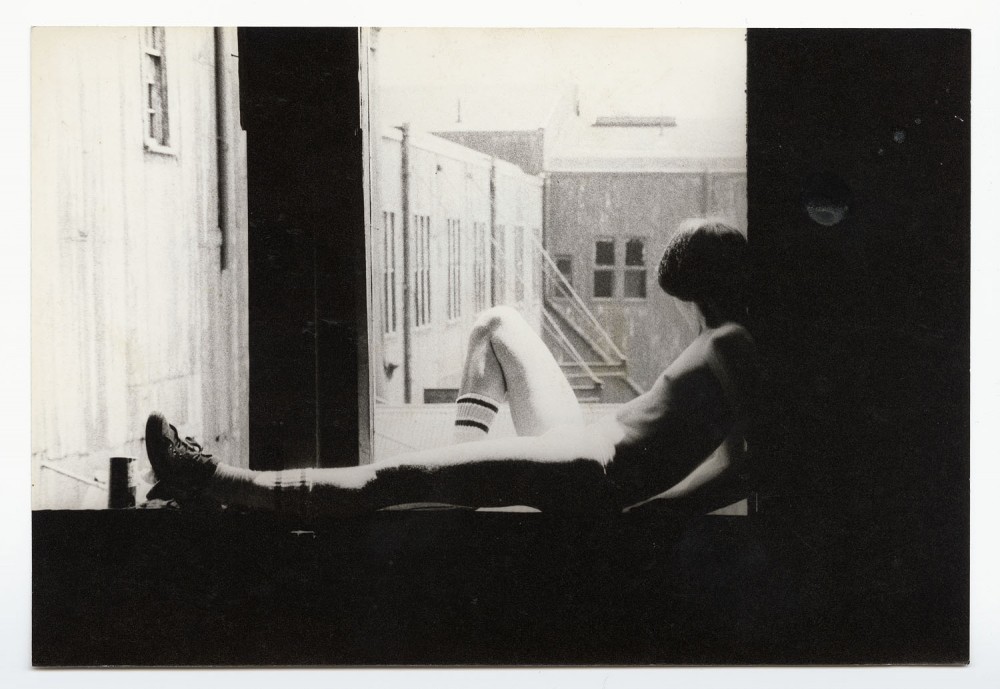

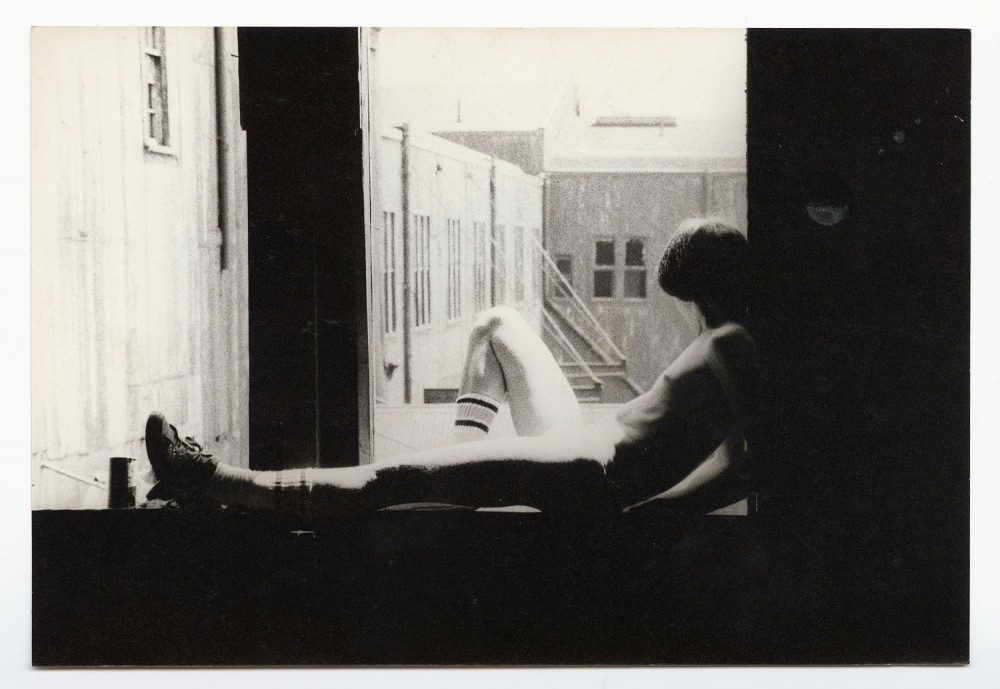

The Piers (man sitting on windowsill). Photograph use courtesy of The Alvin Baltrop Trust, © 2010, Third Streaming, NY, and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York, all rights reserved.

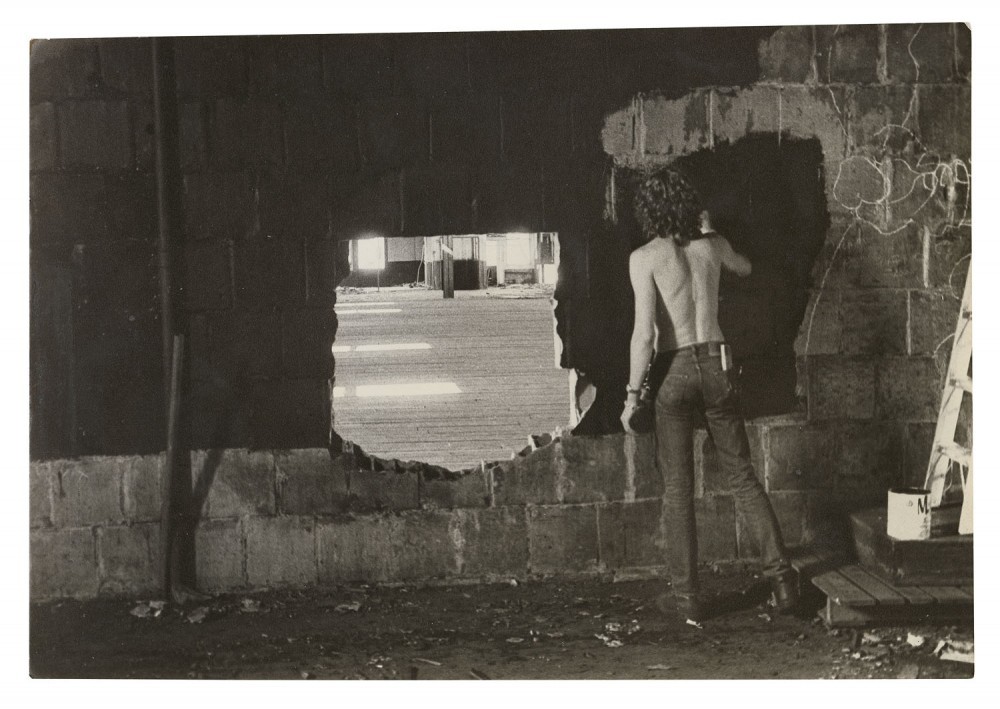

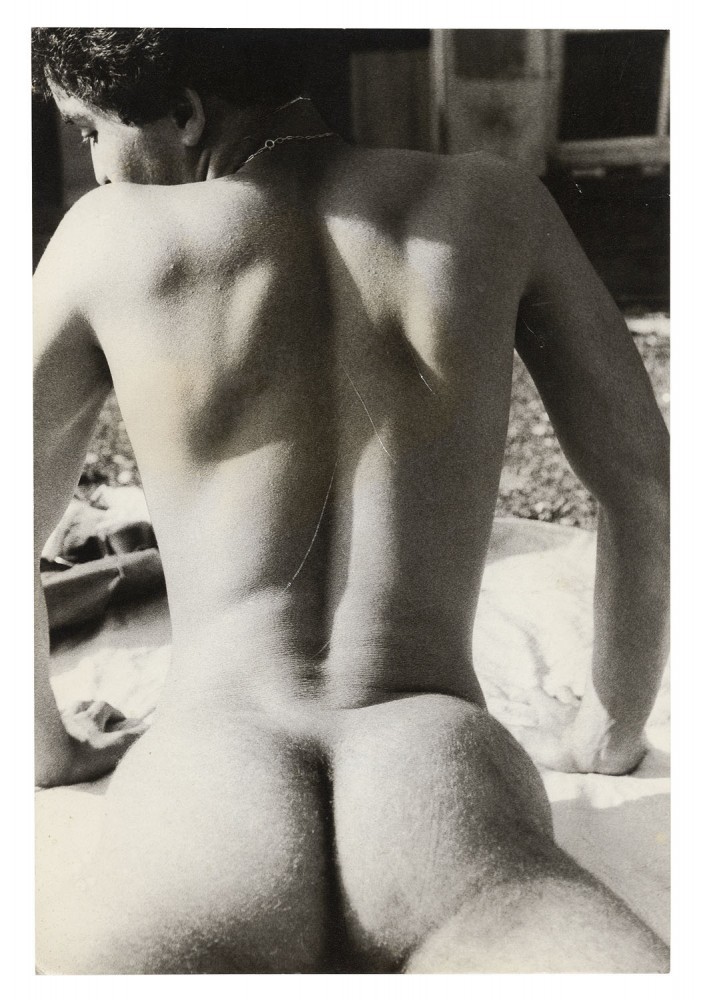

In the summertime the waterfront became even more popular, as guys would venture out across the dangerously decaying wooden boards of the piers during daylight hours to hook up or go sunbathing in the nude. Sitting in the safety of my middle-class living room with my trusty telescope in hand, I spent hours peering down at the goings-on with a curious mix of intrigue, shame, and boredom. My pre-pubescent self didn’t have an overarching concept of these men as “gay,” but simply saw them as mustachioed, muscle-bound, leather-clad, cross-dressing, black, white, brown, nerdy, or homeless. Many of them kept to themselves, and whenever I did see someone cuddle up with his buddy, or one guy’s head go down on another’s lap, it usually appeared strange and distant rather than intimate or exciting. Only after a little while did I come to recognize that something erotic was happening. By contrast, on the rare occasions when I saw a nude woman sunbathing on one of the piers, I would jump to attention with joyful surprise: Tits! Aside from a growing sense of my own sexuality, it was exciting just to get a glimpse of the foreign private parts that were normally so strictly hidden from sight. Zooming in with my telescope, I would try to get the closest view possible, and sometimes I’d even try touching myself with my other hand. The closer I got to puberty, the more I felt there was something unfair in the fact that women were such a tiny minority in this otherwise diverse window panorama.

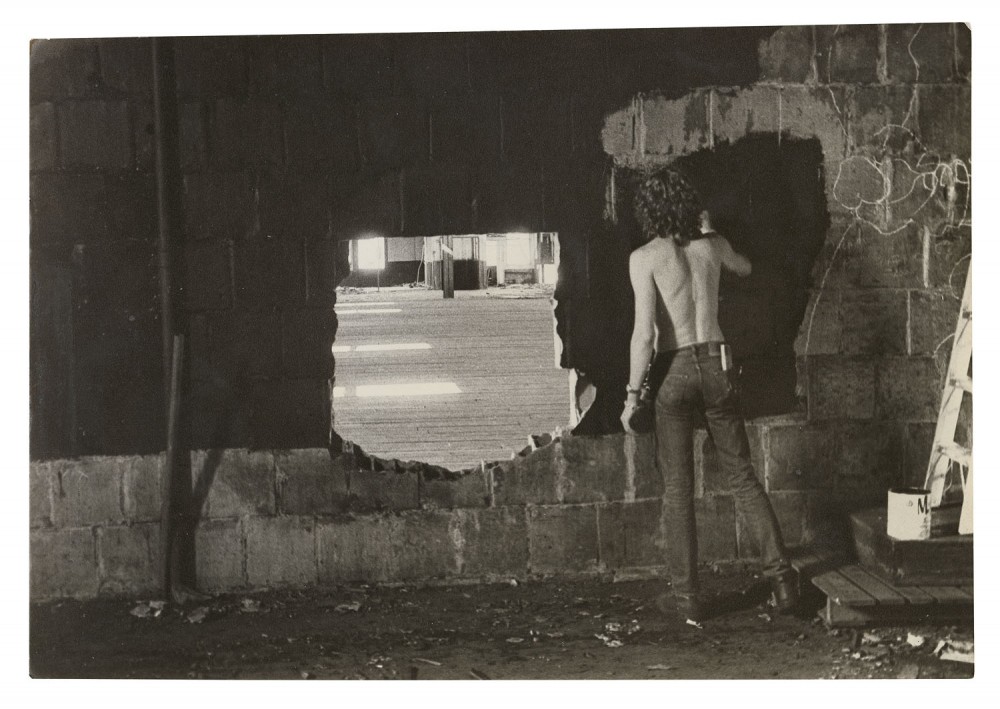

In 1973, a few years before I was born, a 60-foot section of the old West Side Elevated Highway collapsed under the weight of a dump truck at Gansevoort Street, and city planners started reconsidering the neglected waterfront for future development. That same year, Gordon Matta-Clark created an artwork called Pier In/Out, which consisted of a rectangular sheet of metal that had been illegally excised from Pier 14 and transplanted into a gallery space. A couple of years later he made another, more elegiac cutout in the shape of a sail, called Day’s End (Pier 52). Because by this point the shipping industry had abandoned the piers and left the waterfront largely in ruin, Matta-Clark described his memorial architectural work as “making a mark in a sad moment of history.” These uncanny inversions of inside and outside, high and low, center and margin, and public and private feel especially evocative for me as I try to remember what the piers were like before they were dismantled, reconstructed, or burned up in tragic fires. I’m also grateful for having discovered the incredible photographs of the Westside taken during the 1970s and 80s by Alvin Baltrop and Leonard Fink, which document up close and in person the lives that I could only consider from afar. When I look at these images today, I think: They were there! Perhaps I actually saw them when they went out on one of their photo shoots? And perhaps we had something in common at that time: although they were experienced insiders and I was a naïve outsider, we were all voyeurs, them with cameras that captured close-up images for historical record, me with a telescope that left distant impressions in my childhood memory.

Since the development of the Hudson River Park, the former terrain vague now features a long stretch of grass and trees, separate roads for cycling, rollerblading, and promenading, stands for snacks and drinks, public bathrooms, and even a children’s playground. Like the High Line, the waterfront has become remarkably pretty, safe, and family friendly. There are still a lot of sunbathers, but nudity and hanky-panky are no more. And to a large extent the object of voyeurism has been reversed: now pedestrians can get off on discovering exhibitionistic largesse performed from behind the glass curtain walls of the tall buildings above, especially considering that celebs like Nicole Kidman, Hugh Jackman, Calvin Klein, Martha Stewart, and Natalie Portman have each at one point resided in the Perry and Charles Street towers facing the river. Even more provocative are the peepshows of tourist sexcapades in the windows of the Standard Hotel. As one press release put it: “When we built the Standard, we hoped it would provide the best views of New York looking out. We didn’t anticipate that it would also provide those views looking in.”

The Piers (Tava from back), n.d. (1975–86), Photograph use courtesy of The Alvin Baltrop Trust, © 2010, Third Streaming, NY, and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York, all rights reserved.

Of course, risqué images of personal, interior space have become major sources of titillation not only in the big city, but also on television and the Internet. Little boys and girls are stumbling upon plenty of shocking sights and sounds on the web these days, in many ways far more challenging than the kinds of things I used to see in my neighborhood. As urban space becomes more gentrified and homogenized, marginalized communities, isolated individuals and perverts of various kinds may well be retreating further and further into cyberspace. But although computer screens and web cams can now be opened and closed like apartment windows and lens caps, none of them compare to the raw feel of flesh in the street.

Text by Paul Haacke. All images (except where noted) courtesy of The Alvin Baltrop Trust, © 2010, Third Streaming, NY, and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York, all rights reserved.

Originally published in PIN–UP 8, Spring Summer 2010.