A TALE OF TWO CITIES: Mayrit and the Madrid Design Festival

This February the Spanish capital hosted not one but two design festivals simultaneously: the Madrid Design Festival (MDF), now in its third year, and a newcomer, the MAYRIT Festival, also set to become an annual event. Sandwiched between Madrid Fashion Week and the city’s contemporary-art fair ARCO, the MDF takes place over the course of a month, offering a varied program of exhibitions, talks, events, and award ceremonies. It often tends to look abroad for validation, and this year honored the Italian city of Turin, with contributions from the likes of Stefano Cerruti of Bottega Studio Architetti (who was showing his Vittoria modular furniture system), and gave awards to veteran Piedmontese car designer Giorgetto Giugiaro, Shanghai-based architects Neri&Hu, and Swiss graphic designer Bruno Monguzzi. If MDF is in, but often doesn’t quite seem of, Madrid, it’s no doubt due to a belief that the local audience still needs careful grooming when it comes to design literacy: foreign expertise must therefore be imported, and explicitly educational exhibitions put on, such as ¡Funciono! porque soy así — curator Juli Capella’s dissection of the design process through a formal analysis of all sorts of everyday objects — and Esperanza y Utopía at the Museo Nacional de Artes Decorativas, which traces the oft-told tale of early 20th-century design from Behrens to the Bauhaus.

-

Patricia Urquiola, Nature Morte Vivante, an exhibition at Centro Cultural de la Villa, Madrid, curated by Ana Dominguez Siemens for Madrid Design Festival 2020. Photographed by Fernanda Gomez.

-

Patricia Urquiola, Nature Morte Vivante, an exhibition at Centro Cultural de la Villa, Madrid, curated by Ana Dominguez Siemens for Madrid Design Festival 2020. Photographed by Fernanda Gomez.

Since Turin was the guest of honor, what better bridge between Italy and Spain than Patricia Urquiola, who was born in Oviedo before making her career in Milan? If you measure success in terms of the number of prestigious firms that commission your work, then the ubiquitous Urquiola must surely be a contender for the title of “world’s most successful designer”: Alessi, Boffi, Cappellini, Cassina, De Padova, Flos, Kartell, Mutina, and Moroso count among the countless brands she’s worked with over the years — and presumably some of them also helped pay for the thematic retrospective of her work staged at the Fernán Gómez. Curated by Ana Domínguez Siemens, the exhibition was titled Nature morte vivante after a painting by Dalí, which translates as “living still life”: rather than present a chronological dissection of the designer’s oeuvre, Domínguez teased out various themes through a series of eclectically staged tableaux.

-

Patricia Urquiola, Nature Morte Vivante, an exhibition at Centro Cultural de la Villa, Madrid, curated by Ana Dominguez Siemens for Madrid Design Festival 2020. Photographed by Fernanda Gomez.

-

Patricia Urquiola, Nature Morte Vivante, an exhibition at Centro Cultural de la Villa, Madrid, curated by Ana Dominguez Siemens for Madrid Design Festival 2020. Photographed by Fernanda Gomez.

An important factor in Urquiola’s success is precisely her colorful eclecticism, which goes hand in hand with her refusal of a particular signature style (something she shareds with her former professor at Milan Politecnico, the late Achille Castiglioni). While Urquiola is often edgily experimental where materials are concerned — fake leather made from apple skins anyone? —, seeking to push technology and pay attention to the environmental impact of her products, her forms are unapologetically derivative and pleasing, often evoking a comforting, sub-conscious half-memory in the user/viewer. Her sense of humor also often comes through in the show, especially in the names of her products, like her Wasting Time daybed (2019). Made from recycled plastic for Rossana Orlandi, it resembles a giant squashed sneaker, and was shown at the exhibition with a label that nicely summed up some of Urquiola’s pet principles: “I’m the Wasting Time daybed. My ancestors were sneakers and I’m genderless. I speak my own language, no rules or constraints. I’m entirely made of upcycled plastic. You can easily take me apart. My body joints are removable and renewable. At first sight, perhaps, I’m difficult to be liked, but I dare you.”

-

Torres Blancas (1961–69) by Francisco Javier Saenz de-Oiza Torres Blancas. Photography by Ana Amado.

-

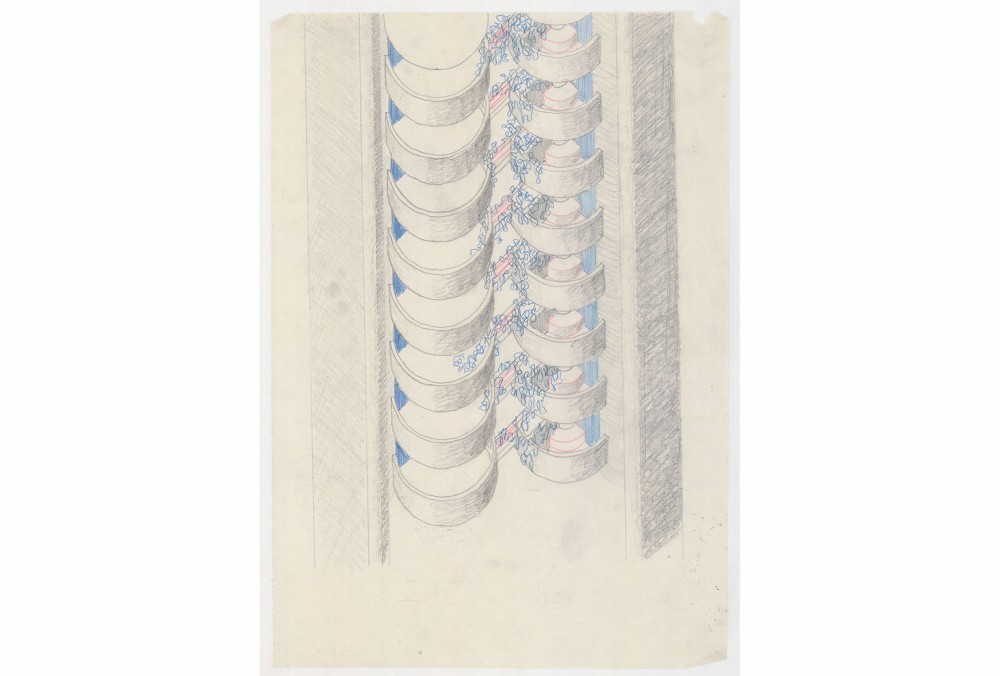

Sketch for Torres Blancas (1961–69) by Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza.

-

Plan for Torres Blancas (1961–69) by Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza.

-

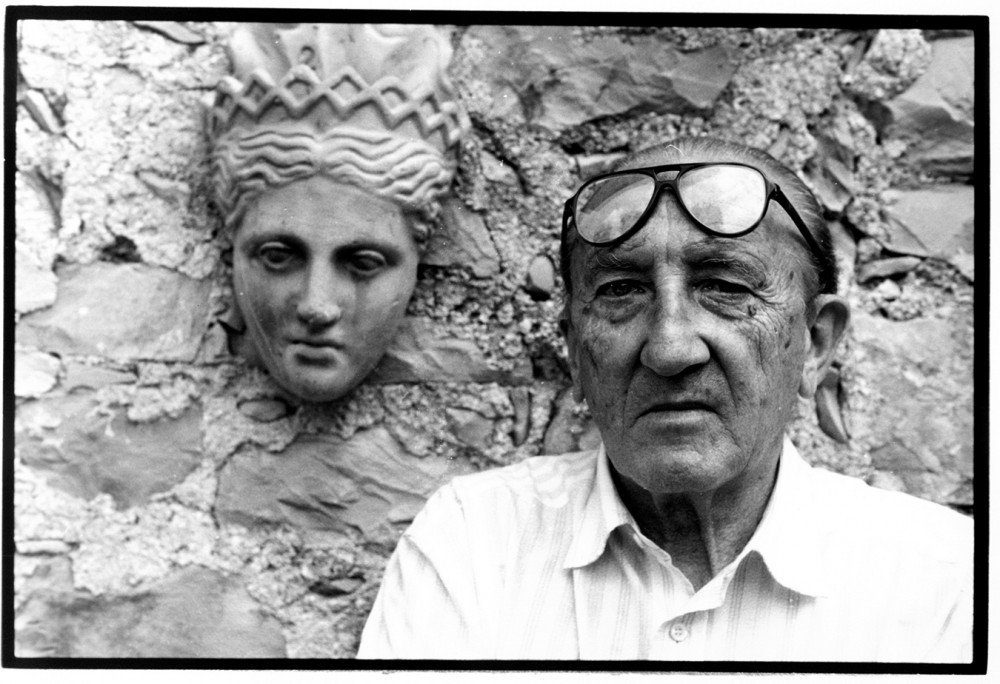

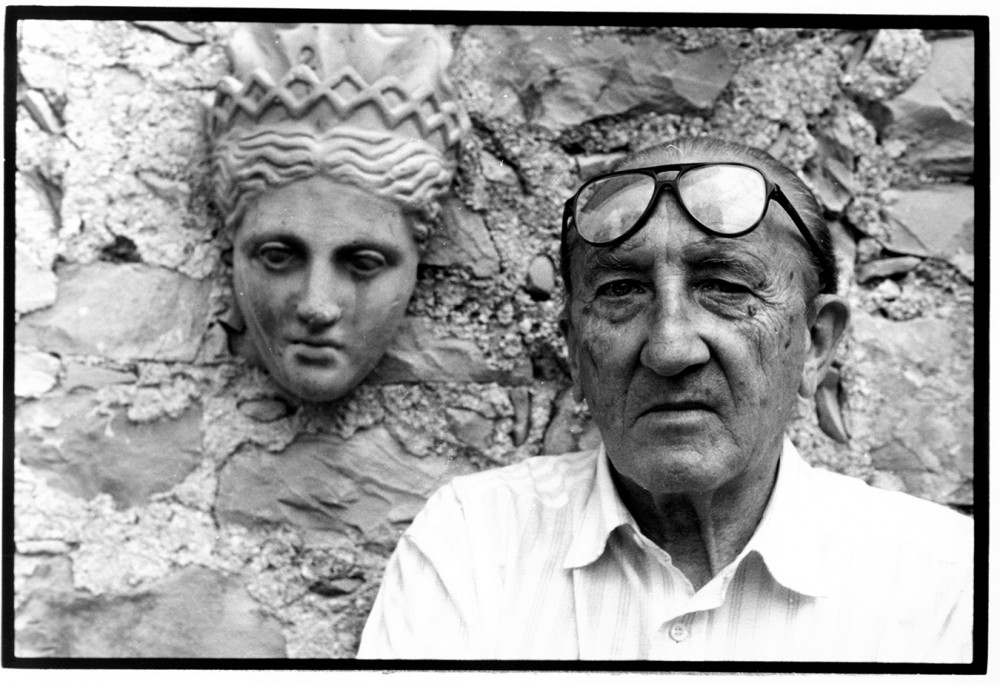

Portrait of architect Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza (1918–2000).

This year’s MDF also brought a long-overdue retrospective of the work of architect Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza (1918–2000), whose most famous building must surely be the Torres Blancas apartment tower (1961–69) in the Madrid neighborhood of Prosperidad. (So illustrious has Torres Blancas now become that a large-scale mural of it can be found in the gentlemen’s restroom of Madrid’s Barajas Airport.) Curated by three of Sáenz de Oíza’s seven children — all of whom became architects and worked with their father —, the show at the Fundación ICO combines the chronological and the thematical, and seeks to go beyond the strictly architectural by giving space both to Oíza’s formative and to the many artists he either frequented or worked with, such as Antonio López, Jorge Oteiza, and Pablo Palazuelo. Though not providing much in the way of analysis of Oíza’s oeuvre, the show and its accompanying catalogue nonetheless offer a touching and evocative glimpse into the rich imaginative universe of an eclectic yet original designer. Like Urquiola, Oíza had no signature style, but his frequent changes in tack produced buildings that almost always have something uncannily unfamiliar about them. His Fundación Museo Jorge Oteiza in Alzuza (1992–2003) bristles with black light cannons; the steel frame of the BBVA Tower in Madrid (1971–81) is reminiscent of an airplane fuselage; and the Viviendas en la M-30 (1986–89), a social-housing complex also known as El Ruedo (“the bull ring”), is PoMo Brutalism at its finest.

-

Architect Belén Moneo arranges pieces of her Emérita collection of shelves and bookends for BD Barcelona. The pieces are made using recycled from several-hundred table legs from a piece her father, Rafael Moneo, had designed back in 2001.

-

Architect Belén Moneo's Emérita collection of shelves and bookends for BD Barcelona. Photographed at Moneo Brock gallery, Madrid.

Over at _2B Space to Be, the office/gallery of architects Moneo Brock, principal Belén Moneo presented her collection of Emérita shelving and bookends. Here again it was a question of architects and their children, since Moneo — the daughter of Pritzker Prize-winning Rafael Moneo — had been asked by the design company BD Barcelona to find a way of recycling a stock of several-hundred table legs from a piece her father had designed back in 2001. Belén took the phallic legs from her dad’s Romana table and chopped them up into bits, combining them with Plexiglas to make shelving, while others she sliced diagonally, adding a flat part mimicking the sectioned leg’s projected shadow to create colorful bookends. Despite the castrating violence of the gesture (the legs were shaped like a quarter of a fluted column, and as such are an obvious signifier of the Classical, antique, patriarchal world), Belén assured us that her father liked the results.

The MAYRIT festival 2020 logo graphic identity by Victor Clemente was inspired by water. The word mayrit comes from the Arabic term Mayra (meaning water or giver of life), which later changed to Magerit, which means "place of water" in Arabic. The name then evolved to Matrit and then eventually, Madrid.

While the now-established MDF focuses on mostly well-known names, the new MAYRIT festival complemented the MDF by highlighting the young local design scene, most of it largely unknown, both in and outside Spain. As a result, where the MDF is generally confined to what one might call Ava Gardner’s Madrid (the Hollywood legend lived there for 13 years, hanging out in the city center’s historic nightspots with Flamenco star Lola Flores), MAYRIT takes place in Madrid’s more affordable outskirts, the city of Cuéntame cómo pasó (a long-running Spanish TV soap set in a working-class neighborhood) where abuelas with improbable helmet hair gather nightly in the local bar to gossip over cañas, bocadillos and platefuls of croquetas. This is partly what dictated the festival’s format, as its founder, 25-year-old designer Miguel Leiro, explained: lasting ten days, it consists in a series of ephemeral exhibitions and events that take place in multiple locations. As for the festival’s title, mayrit is the old Arabic denomination for the backwater settlement that King Philip II would choose for his imperial capital in the 1560s, and most likely translates as “place abundant in water,” given that the area is rich in streams and springs. For Leiro, this is both a metaphor for design — Madrid as a source of abundant creative energy — and also acknowledges the wider Madrid-basin network that irrigates both the city center and the local design scene (water also inspired the MAYRIT logo, designed by Victor Clemente).

-

The show Órbitas presented recent and previously unreleased work by Inés Llasera and Guillermo Trapiello, also known as Tornasol Studio. Photographed by Asier Rua for MAYRIT.

-

The show Órbitas presented recent and previously unreleased work by Inés Llasera and Guillermo Trapiello, also known as Tornasol Studio. Photographed by Asier Rua for MAYRIT.

-

The show Órbitas presented recent and previously unreleased work by Inés Llasera and Guillermo Trapiello, also known as Tornasol Studio. Photographed by Lucia Ugena for MAYRIT.

-

The show Órbitas presented recent and previously unreleased work by Inés Llasera and Guillermo Trapiello, also known as Tornasol Studio. Photographed by Lucia Ugena for MAYRIT.

-

Arranging Porcelain by Tomás Alonso in collaboration with Arita. On view at Aparador Monteleón, an artist-run exhibition space curated by Javier Montoro. Photographed by Laura San Segundo for MAYRIT.

-

Desert Plateau, Parasite 2.0 and Studio La Cube's at the Polytechnic University of Madrid’s school of architecture. Photographed by Asier Rua for MAYRIT.

“Design in Madrid is both a cultural and social force,” Leiro told PIN–UP, “and has a lot of potential for development. Part of the idea behind MAYRIT was to understand and conceptualize the idea of a collective group. But I also wanted to challenge the idea of what a festival is and how people interact with it.” Festival-going MAYRIT style consequently demands a certain frontiersman spirit: one night you might find yourself in the southern neighborhood of Usera, standing in a borrowed studio space admiring an exhibition of new pieces by the excellent Tornasol Studio (Inés Llasera and Guillermo Trapiello), including an armchair made from purple inflatable mooring fenders, another from a section of glass-fiber paddling pool, a balancing cork stool held together with a marine bungee cord, etc. The next night you’re out west, on the way to Barajas, at the Madrid premises of Swiss aluminum-window manufacturer Panoramah!, for a group show entitled Liminal Encounters. In their lobby a host of young designers had dreamt up aluminum waiting-room pieces, including a slick black folding screen by Leiro, floor lights by Milan-based Piovenefabi, a stunning glass coffee table by Tornasol Studio, and a set of side tables by Selina Feduchi that recall the lakes of red bauxite waste created in the production of aluminum.

-

Objects from Ceniceres Siempre, a workshop led by designers Julen Ussia and Joel Blanco during Madrid Design Festival/MAYRIT in February 2020. Photographed by Asier Rua for MAYRIT.

-

Extraperlo, an exhibition at Espacio Gomina curated by Jorge Penadés and featuring work by Matylda Krzykowski, Attua Aparicio, Odd Matter, Juan García Mosqueda, Fredrik Paulsen, and Lex Pott.

-

Liminal Encounters, a group show in collaboration with Swiss aluminum-window manufacturer Panoramah! Participating designers include Miguel Leiro, Piovenefabi, Tornasol Studio, Selina Feduchi, Fabien Cappello, MAIO, Teresa Fernández-Pello, Claudia Paredes, and Objects of Common Interest.

Other MAYRIT events were more unusual in the context of the overall design festival. Take Ceniceres Siempre, for example, a clay-modeling workshop led by designers Julen Ussía and Joel Blanco in an art gallery in Puerta del Ángel, where participants were asked to sit on the floor making ashtrays. “I’m looking to develop even more variety in typology and formats, with public installations, debates, lectures, and participatory happenings,” explains Leiro, who is already planning for next year’s edition. “Maybe the festival should move to a warmer time of year — the Madrid experience has a lot to do with being outside after all.”

Text by Andrew Ayers.

All images courtesy Madrid Design Festival and MAYRIT.