SCENTS AND SENSIBILITY: RUMINATIONS ON PERFUME’S POLARIZING NATURE

The Oxford English Dictionary defines perfume as “a fragrant liquid used to impart a pleasant smell to one’s body or clothes.” Yet scent represents so much more than this. It’s a language of self-expression, identity, and emotion connected to our conscious and subconscious selves. Your point of view, your opinions, the way you see the world can all be expressed without ever opening your mouth. As eloquently put in the tagline for ex´cla·ma´tion — the iconic drugstore perfume launched in 1988 by Coty and still sold today —, wearing a scent allows you to “Make a statement without saying a word.” In a culture filled with visual and audio stimulation, fragrance is an invisible but powerful medium of expression, as thousands of perfume taglines over the decades have underscored. As statements of intent, they deliver camp pearls of wisdom that can compete with some of the best one-liners from the likes of RuPaul, Mae West, Joan Rivers, or Diana Vreeland. Calvin Klein undoubtedly stands out as a master of taglines, from 1985’s Obsession (“Between love and madness lies Obsession”) to 1988’s Eternity (“Always and Never the Same”) and 1994’s CK One (“We are one”). Chanel’s Égoïste (1990) was so brilliant it didn’t even need a tagline, the name said it all. In the legendary commercial, directed by Jean-Paul Goude, women scream a line from Corneille out of the windows of what looks like a tropical version of the Hôtel Le Negresco in Nice: “Égoïste, where are you? Stop hiding, selfish man! Watch my ire! I will be implacable! O anger! O despair! You betrayed my love. Have I lived simply to know this infamy? Show yourself! Égoïste!” (That said, some of the best perfume taglines are purely fictional, whether it’s Grace Jones’s legendary scene in Boomerang pitching her scent Strangé to a boardroom full of executives — “It stinks so good” — or Miss Piggy’s Moi — “Why be you when you can be Moi?”)

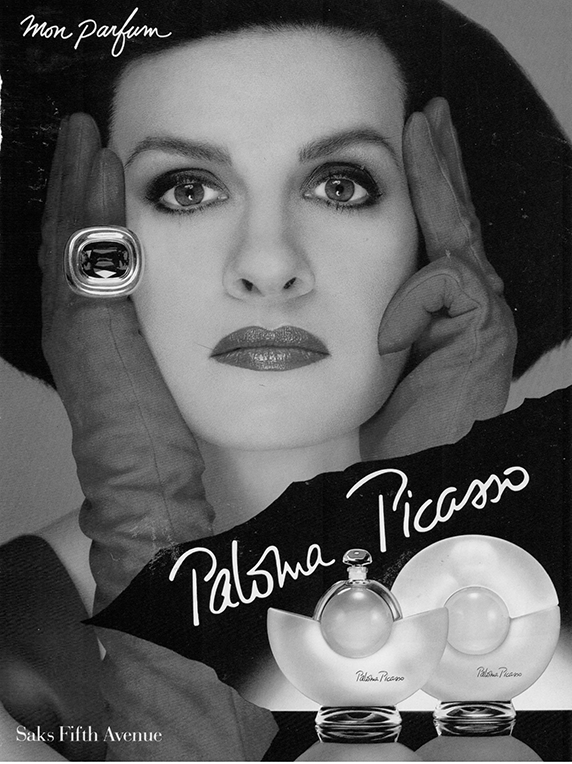

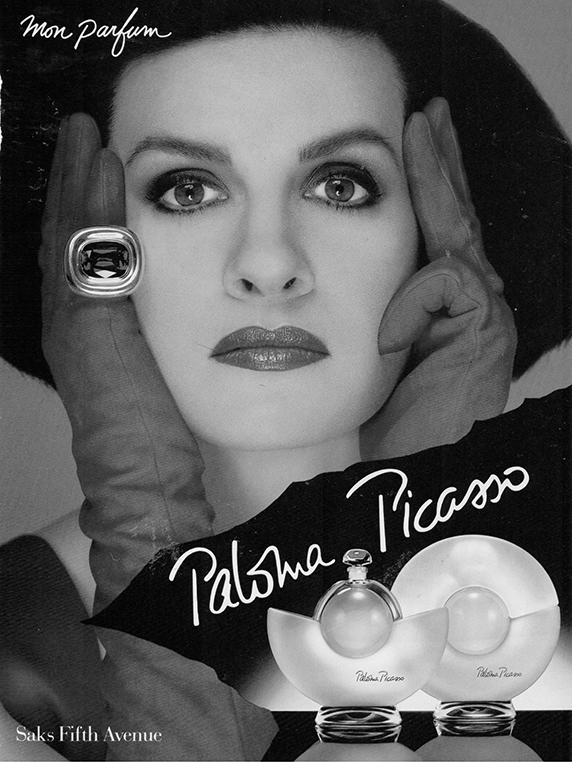

Advertisement for Paloma Picasso’s eponymous Paloma, c. 1984.

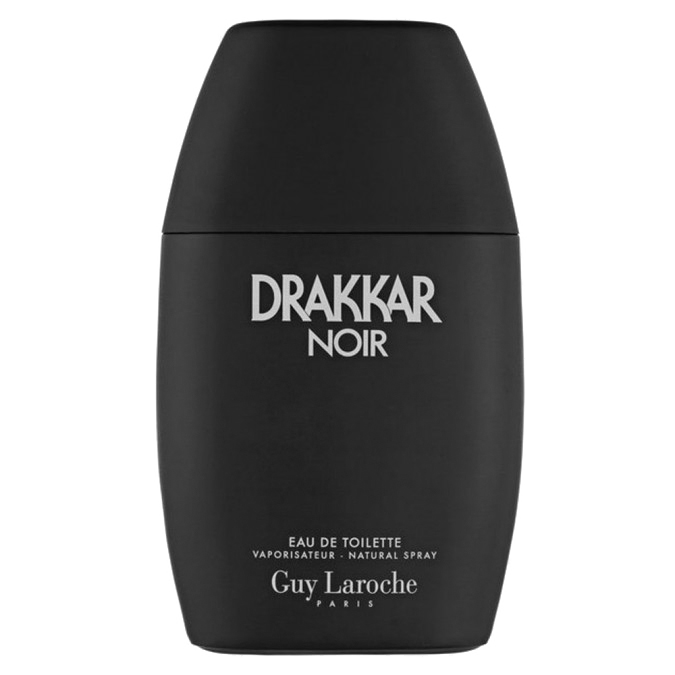

Like film, music, and other art forms, scents aren’t just a means of expression but can also have visceral effects on providing or inducing comfort and reviving memory — fragrance is about the closest we can get to mainlining nostalgia. I remember going to the mall as a twelve year old and being spritzed with Paloma Picasso’s eponymous Paloma (1984), encased in a fried egg made from glass and black plastic. The scent (and the bottle) represented a fragrant self-portrait of its creator — sophisticated, eccentric, original, and well-traveled. I was utterly beguiled. “A combination of bergamot, lemon, hyacinth, angelica, ylang ylang and touches of clove. At its heart, a bursting bouquet of flowers: rose de Mai, jasmine, iris and lily of the valley, rounded out by a blend of oak moss, vetiver, patchouli, civet, amber, musk, cedarwood, tobacco and sandalwood” — what more could an aspiring eccentric ask for? That misting in an Ohio mall made me suddenly feel like the chicest woman in Marrakech. In Paloma’s own words, “A perfume is like a piece of clothing, a message, a way of presenting oneself … a costume … that differs according to the woman who wears it.” A couple of years later, my eighth-grade boyfriend was wearing Drakkar Noir (all the popular boys did), a Guy Laroche scent first released in 1982 with ad campaigns shot by the likes of Herb Ritts and Jean-Baptiste Mondino and a print tagline that read “Where Gentle Strength Triumphs.” It even managed a mention in Bret Easton Ellis’s movie American Psycho. The bottle is seductively matte black with outer edges that curve sensually for an erotic grip, while the white pointy font evokes the testosterone of a medieval jousting match.

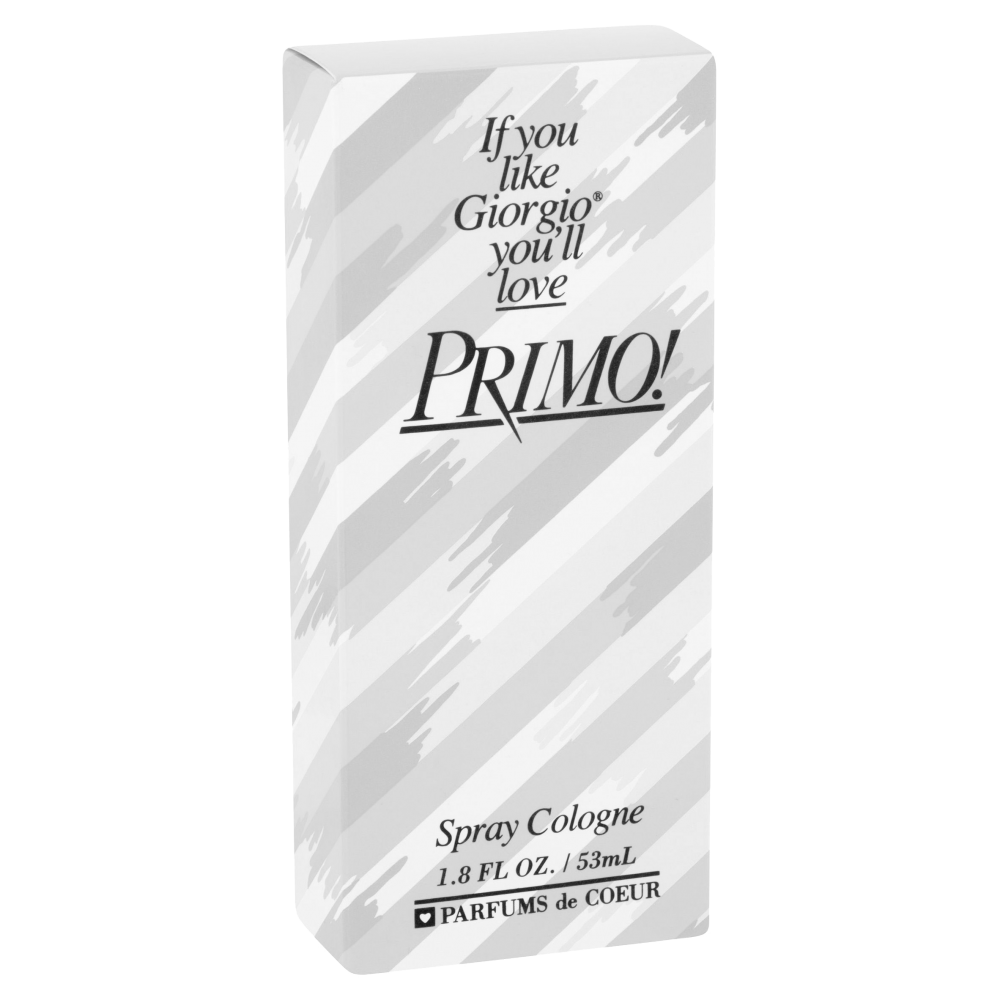

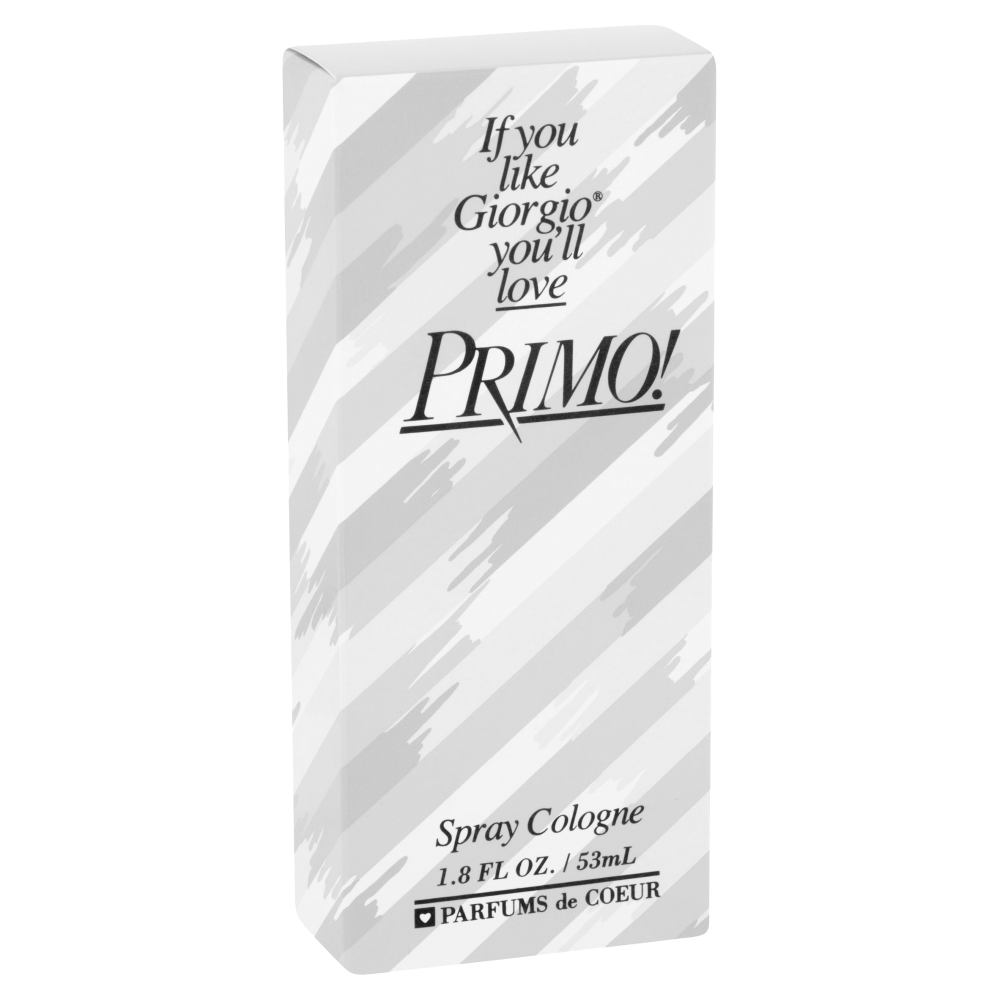

Designer imposter perfume Primo.

While it was scents by the likes of Picasso and Laroche, with their promise of European luxury, that conjured my emotions, it was the increasingly popular designer imposters (“If you like Giorgio you’ll love Primo!”) that made it possible for people like me to join the cult of scent on my babysitter budget — nothing buys brand loyalty like teenage nostalgia. In that sense, the late 1980s and early 1990s were also a democratizing era of fragrance, with body sprays geared towards a teen market becoming available at stores around the country at relatively affordable prices. My best friend in high school, Lisa Sweirs, religiously wore Electric Youth by teen sensation Debbie Gibson (1989), spraying it on her hair and on her pillow at night. While the visual of Electric Youth’s bottle — a hot-pink Tesla coil suspended in the amber liquid of my youth — is burned into my memory, so is its smell forever associated with a rebellious teenager, underage drinking, and driving around desolate backcountry Ohio in a Camaro with Metallica blasting. Both Debbie Gibson and Lisa Sweirs live on for me in that scent. Another one of my personal favorites, Tribe (1991) — “A Fragrance Uprising” —, featured a gang of gorgeous girls, foreboding Stacey Dash and Alicia Silverstone in the mid-90s classic Clueless, crammed into a baby-blue convertible filled with shopping bags and laughing in defiance. The graffiti-style logo emblazoned in neon on the side of a lipstick-inspired dispenser was the ultimate badge of coolness. It made me feel like the popular girl I wanted to be — I was part of “the tribe.” Then there was Fetish (1997) by Christina Aguilera (the first of many) that came in what looked like a Memphis Group-designed pen that clipped onto your bra strap for easy access. “Apply generously to your neck so he can smell the scent as you shake your head ‘no’” was the tagline — an empowering statement that felt very much in sync with my growing sense of girl-power activism.

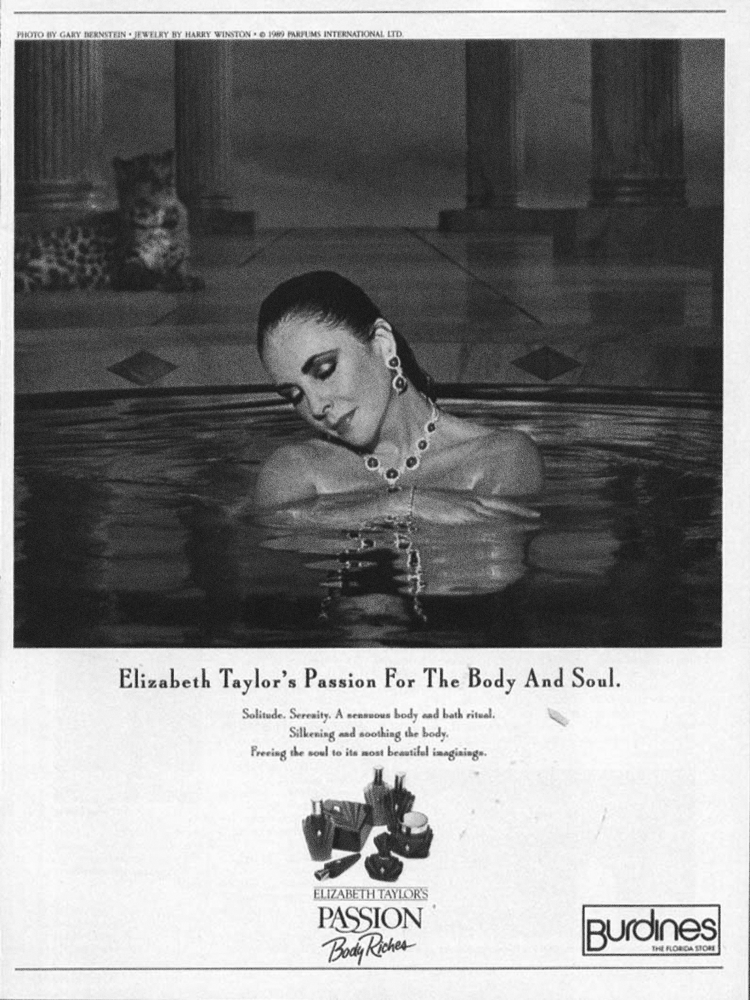

Advertising for Elizabeth Taylor’s perfume Passion, c. 1988.

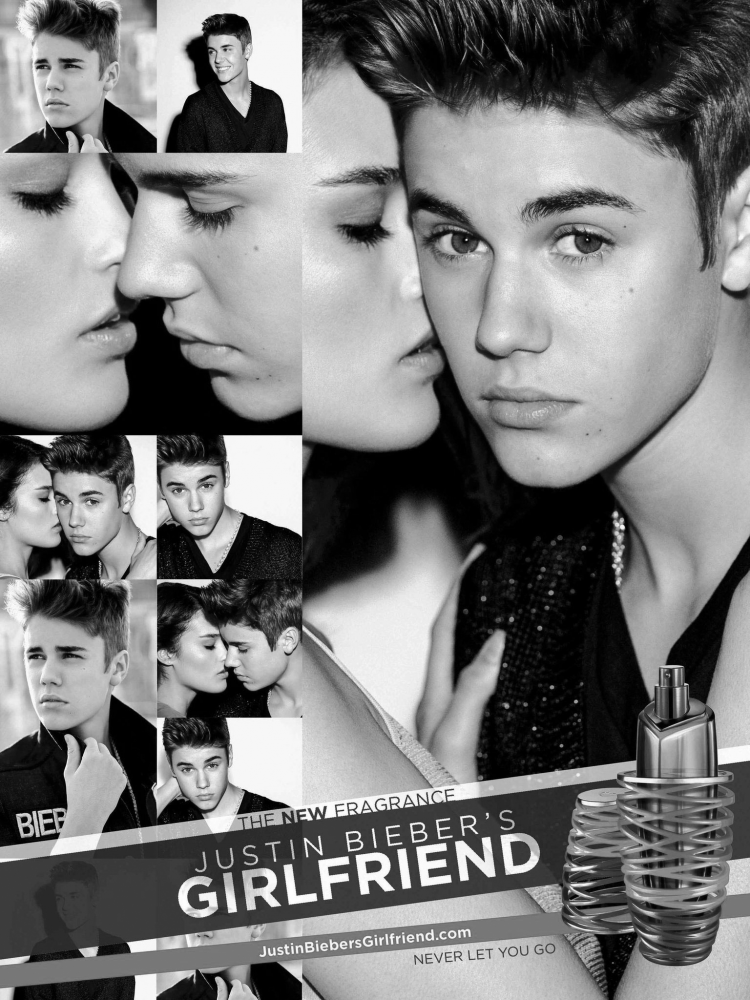

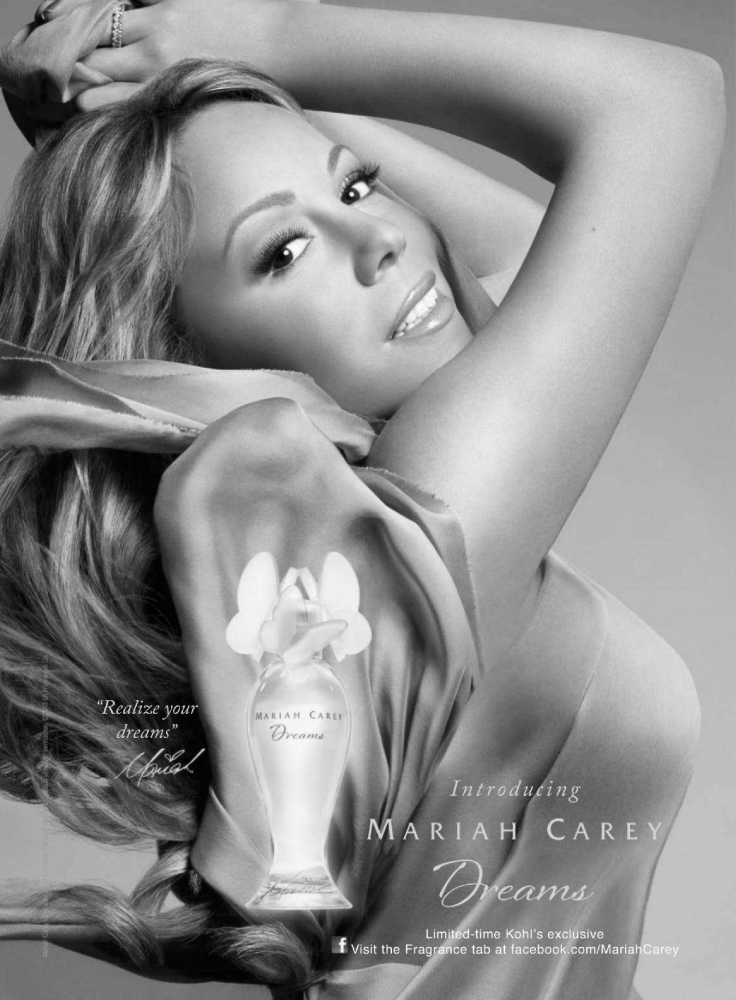

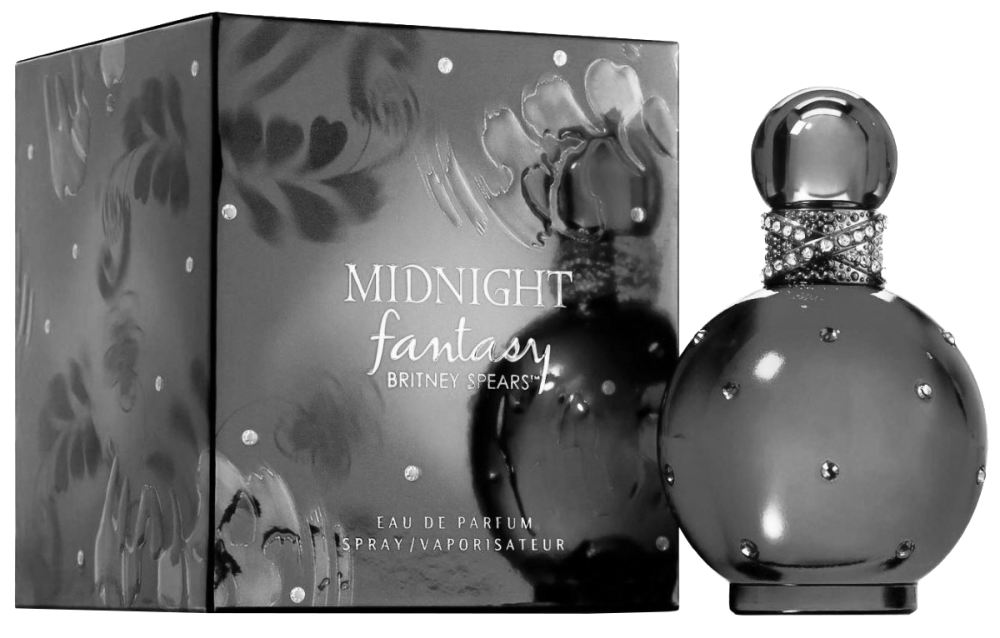

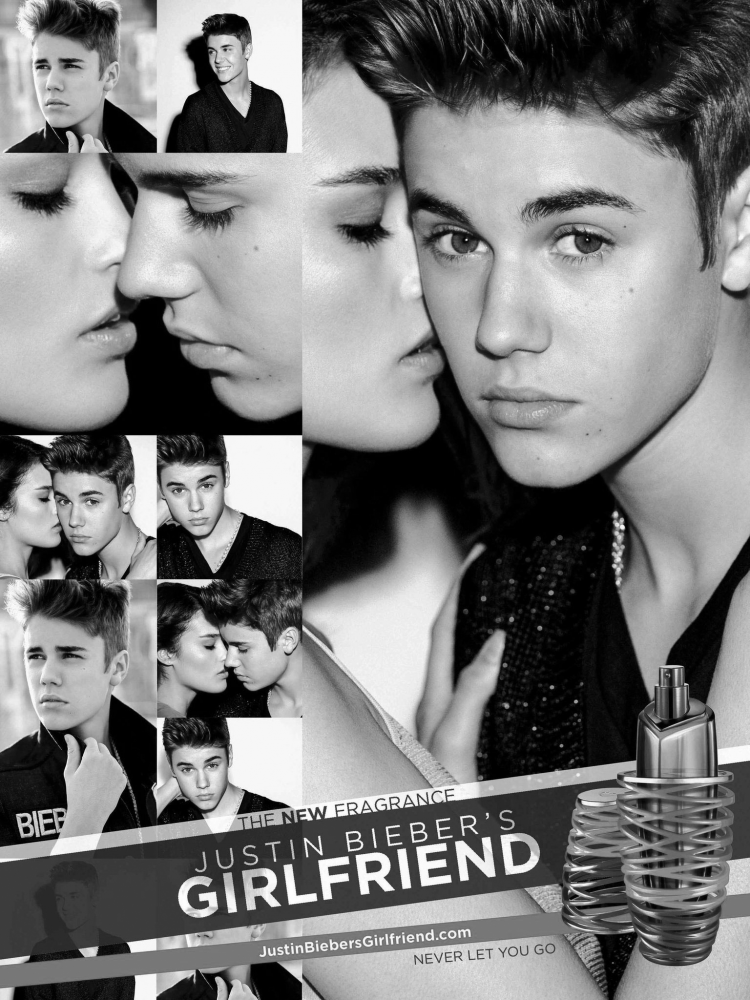

Speaking of celebrities, ever since 1987, when Elizabeth Taylor bottled her Passion and put it on the market, celebs have saturated the market with their scents. Are you Justin Bieber’s Girlfriend (2012), Britney Spears’s Midnight Fantasy (2006), Beyoncé’s Pulse (2011), Mariah Carey’s Dreams (2013), Kim Kardashian’s True Reflection (2012), or Jennifer Lopez’s Glow (2002)? But it’s not just an easy way for the famous to augment their fortunes along the way (12 dollars 99 cents for a 1.75-fluid-ounce bottle of Passion, that is), or to mark one’s cultural territory — it’s about maintaining the belief that the extravagant lifestyle is attainable, that one isn’t so far away from being a VIP after all. The aspirational status of each celebrity is the major selling point, but so is the bottle in which the fragrance is sold. Often the bottle design is left to in-house design teams, but there are a few stars among perfume-bottle designers. Paris-based Pierre Dinand, a trained architect, was the designer behind iconic flasks like Yves Saint Laurent’s Opium (1977), Joy by Jean Patou (1984), Moschino’s Cheap and Chic (1995), as well as Calvin Klein’s Obsession (1985) and Eternity (1989). Marc Rosen in New York is the design genius behind Elizabeth Arden’s Red Door (1989) as well as a number of scents for Karl Lagerfeld, Christina Aguilera, and Céline Dion, to name but a few. Fabien Baron gave the world the iconic CK One (1994), Viktor & Rolf’s Flowerbomb (2005), and Madonna’s Truth or Dare (2012). Out of the sea of celebrity scent bottles, a recent one to stand out is Nicki Minaj’s Pink Friday (also 2012). Designed by Lance McGregor, it pays homage to the now legendary Jean Paul Gaultier atomizer shaped like a bustier (Classique, launched in 1993). Nicki’s bottle hits all the marks: the perfect features of her face, rendered in a shiny metallic gold and crowned with a pink-plastic wig, form the cap, while the eau is housed in her busty torso. What it smells like hardly matters when your bottle looks like a Jeff Koons sculpture in miniature — an important trait that can make or break its appeal as a product. Another winner is Angel, the olfactory equivalent of the power suit. Launched by Thierry Mugler in 1992, it is still to this day one of the highest grossing perfumes in history. The bottle, a glass star of angular proportions hand-crafted by Brosse Master Glassmakers, required the invention of a new glassmaking method, which took three years to develop. The result is an industrial-design triumph: not only is the bottle, designed by Mugler himself, a testament to innovative design, but the scent itself was one of the first oriental-gourmand fragrances — “I wanted there to be such a sensual contact with this perfume, that you almost feel like devouring the person you love,” said Mugler. The bottle is refillable from what he calls “The Source” — an eternal refill available in stores that reinvents the 18th-century tradition of perfume fountains. In the end, the way in which fragrance is packaged can be just as important as its olfactory effect. I’m not sure most people even care what Chanel N°5 smells like — the bottle of what is still the most popular perfume in the world stands on its own.

Pink Friday by Nicki Minaj, c. 2012.

Of course, for those that do care, a perfume’s smell can be a very intimate experience — both to them and their entourage. The power, seduction, and mystery of scent can transform one’s identity and the perception of oneself by others, lingering long after you’ve exited a room. Hence cultivating a “signature scent” is a powerful tool. Add to that the fact that no perfume smells the same after being applied to the skin of the individual — once mixed with our particular set of pheromones, the bottled scent from a mass-produced fragrance becomes uniquely our own — and you see where a fragrance’s true power lies. I discovered this power in my mid-20s, when I dedicated myself to finding my signature scent. In the words of Coco Chanel, “A woman who doesn’t wear perfume has no future.” The triumph of being recognized by my one scent — Scent Intense by Costume National (2002) — is something I now take great pride in. After many years, my scent and I are irrevocably linked. According to my friends, family, and acquaintances, it provides them the same sense of comfort I once received from others in the recognition of their unique smell. It’s an almost primal camaraderie that makes us feel safe and protected. But in the same way that fragrance can provide a sense of comfort, it can also elicit extreme levels of discomfort, and polarize in an instant. A friend of mine wears an oil that smells exactly like Jamaican brick weed smoked through a fabric-softener sheet — and I absolutely love it. Meanwhile my least favorite odor is Febreze air freshener — to me it smells like dirty gym clothes meet floor cleaner. My personal scent space is also unpleasantly invaded by wafting clouds of what I call “brunch colognes,” often encountered on Sunday-afternoon strolls through SoHo. The same goes for veering too close to the Bath & Body Works store in a mall, where you drown in the cloying scent of peach melba or sweet vanilla cinnamon. Based on my own research, the most divisive scent is a toss up between Polo Sport (Ralph Lauren’s 1994 cologne) and patchouli — like the British yeast-extract spread Marmite, you either love it or you hate it.

Scent Intense by Costume National, 2002.

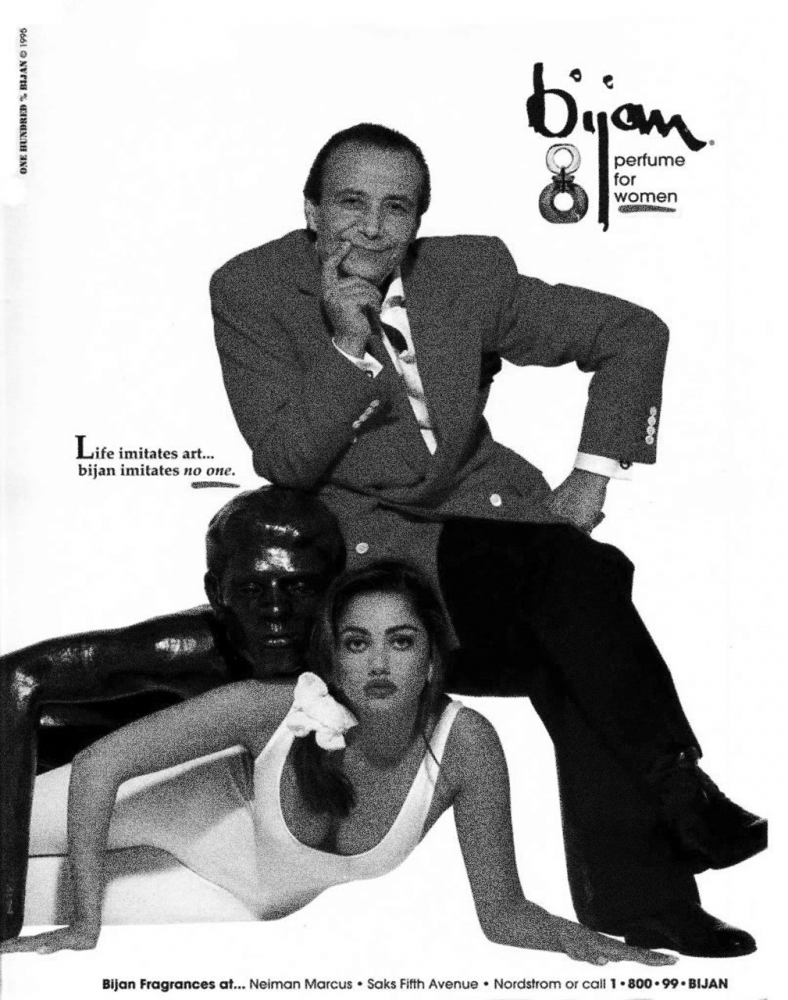

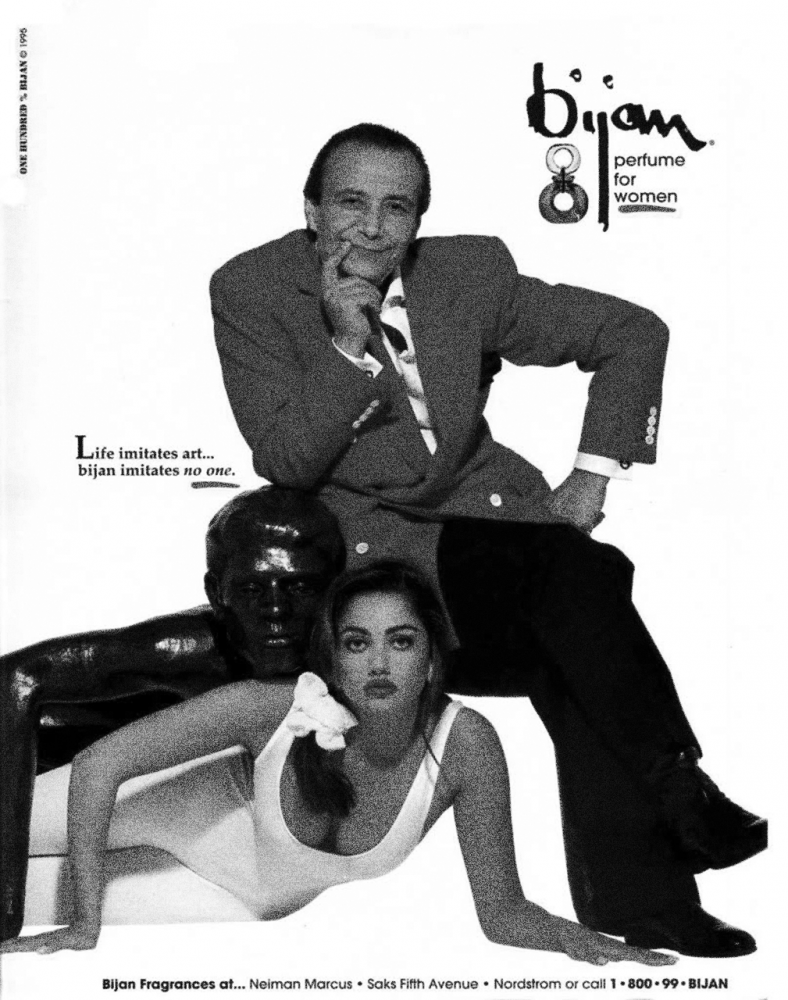

After brand-name recognition, bottle shape, and of course the actual scent, the fourth important success-defining element of a perfume is its advertising campaign. Usually devised for periods of time that go far beyond the seasonal cycle of fashion advertising, the aesthetics of fragrance campaigns function as cultural barometers, making explicit society’s desires and excesses, our relationships to sex, love, youth, and intimacy. What is controversial in other commercial mediums is embraced in fragrance marketing. The statements made are unapologetic. The art of fragrance is unfiltered. In 1971 Yves Saint Laurent famously (and for many, shockingly) posed nude for the launch of his perfume Pour Homme. In 2007, Tom Ford, never one to be outdone, ran a campaign in which a bottle of his eponymous perfume was placed on women’s shaved genitalia. Decidedly less explicit, but among the most iconic, was the perfume launched in 1987 by Bijan Pakzad, an Iranian-American menswear designer whose Beverly Hills appointment-only store Bijan was known as “the most expensive in the world.” The bottle itself of Bijan’s eponymous perfume is unrivaled, and one is actually featured in the permanent exhibit of the Smithsonian Institution. But more importantly, Pakzad took the perfume-design concept to meta levels with his ad campaigns. With a flashy tagline — “Life imitates art. Bijan imitates no one” — Pakzad himself often featured prominently in the ads that used to run in every magazine and were plastered across billboards in any bigger city. In one, actress Bo Derek, wearing a white trench, is seen from behind, flashing Pakzad and what is presumably his grandson (who’s covering his eyes). In another, Pakzad sits atop a glamorous model in a white skintight jumpsuit, crouched beside a male figure (or is it a sculpture?) that looks as if he was dipped in black tar. After all these years I’m still not sure what statements Pakzad was trying to make, but I was sold, and the images continue to haunt me to this day.

Advertising for Bijan Pakzad’s eponymous perfume from the mid-1990s.

The practice of endowing perfume with the same status as religious iconography seems to have faded in recent years. In an age of dwindling advertising budgets and a general demise of print (farewell smell strips!), the often short-lived celebrity scents are now largely promoted digitally through social media. What if you could scratch and sniff an Instagram post? Virtual memory and perceived experience have made it possible to create tangible worlds without a physical presence. In the future, without the limitations of creating a physical package for an actual scented liquid, the idea of a scent could be manipulated and marketed purely as aspirational. With little-to-no overheads on the physical product, the potential for profit would be much higher and the boundaries for exploration much greater. And what happens to scented air in a gravity-free world? What’s the signature scent of your avatar? Can your Twitter posts have a signature scent? Can you upload and attach a signature scent to specific contacts in your phone to emit a waft of fragrance in place of caller ID? And if Tinder included a scent sachet in every profile, would it make it easier to weed out the undesirables? But even beyond the advent of scented technology, what about the total eclipse of the undetectable: the scent of virtual reality. Much like spending 100 dollars on an emoji of a spliff on Snoop Dogg’s hit-sticker app Snoopify, or purchasing a diamond emoji for 100,000 dollars (yes, Paris Hilton), status through smell could be the new Hublot watch.

Justin Bieber’s Girlfriend, 2012.

So just as YouTube and the lexicon of social-media platforms democratized the output and consumption of music and film, the digital technologies of the future are now a new frontier for redefining the concept of the signature scent. Individuals will soon be able to self-create, release, socially share, and generate fragrance without the need for beauty conglomerates like Estée Lauder, Coty, and their ilk. Various such olfactory technologies are already emerging. Printer prototypes containing aroma cartridges that will one day evolve into consumer-fragrance generators are in the development stage. Meanwhile Harvard professor David Edwards has created oSnap, a scent-messaging app that will enable users to create and send scented images (oNotes) via mobile messaging — the iTunes of aroma. The figurative scent will replace the literal scent attached to an image, birthing what is now dubbed the “smelfie.” Through technology our senses have taken on new strengths, our sensory reach has expanded — we are now accustomed to sensing things by simply seeing, we can conjure the experience of touch, smell, and sound. The goal of so many technologies is to create an immersive space that tricks our brains into believing we are physically and emotionally part of the experience we are watching. These innovations have the potential to create a virtual-reality experience that fully immerses all our senses. Sony is taking this idea to the next level by injecting smells into gaming: in a 2013 patent application, the Japanese firm described a process of “overlay(ing) non-video content on a mobile device” which “will allow olfactory content to be overlaid into the content of video games,” permitting the user “to smell what the actor smells at that point in the movie.”

As long as we have skin and the ability to smell, the perfume industry — currently worth upwards of 36-billion dollars annually — will continue to exist. But how its products are generated and distributed will transform, and if they don’t acknowledge the paradigm shift put forth by our growing obsession with virtual space, blockbuster perfumes like Mugler’s Angel, and Calvin Klein’s Eternity will be met with the same fate as Blockbuster Video in the 2000s: left behind, with just a lingering smell of corporate burn-out.

Text by Gerlan Marcel.

Taken from PIN–UP No. 23, Fall Winter 2017/18.