Speaking in Tongues: on the Swiss Institute’s Sable Elyse Smith-Curated Annual Architecture and Design Series

Sondra Perry, Title TK 5, 2018. Spalding universal shot trainer, painted steel, hardware. Photo by Daniel Pérez, courtesy of Swiss Institute.

There is a state of delirium associated with speaking in tongues, an ecstasy-filled experience that coerces someone to string together strange words that confound language itself. However, the Swiss Institute’s annual architecture and design series exhibition, curated by Sable Elyse Smith, asks viewers to think about what happens when you look beneath the tongue. Moving away from pure visuality and towards an understanding of the various languages brought forth when translating a work of art’s intentions, Beneath Tongues spans two floors and brings together 15 artists; E. Jane, Carrie Mae Weems, Cudelice Brazelton IV, Abigail DeVille, Nikita Gale, Lydia Ourahmane, Sondra Perry, Steffani Jemison, Lauren Halsey, Patricia Satterwhite, Jacolby Satterwhite, Carolyn Lazard, Jennie C. Jones, Jessica Vaughn, and Christine Sun Kim. This exhibition also includes a musical score by Smith, Tariq Al-Sabir, and Freddie June that plays throughout the second floor, co-mingling with the sounds of the various artist-made playlists that you can listen to on the headphones that line the room. Where the first floor focuses on works that are more often deemed “traditional” art objects, the second floor is somewhat of an ideological departure, providing space for viewers to piece together how exactly the work downstairs is communicating to them.

-

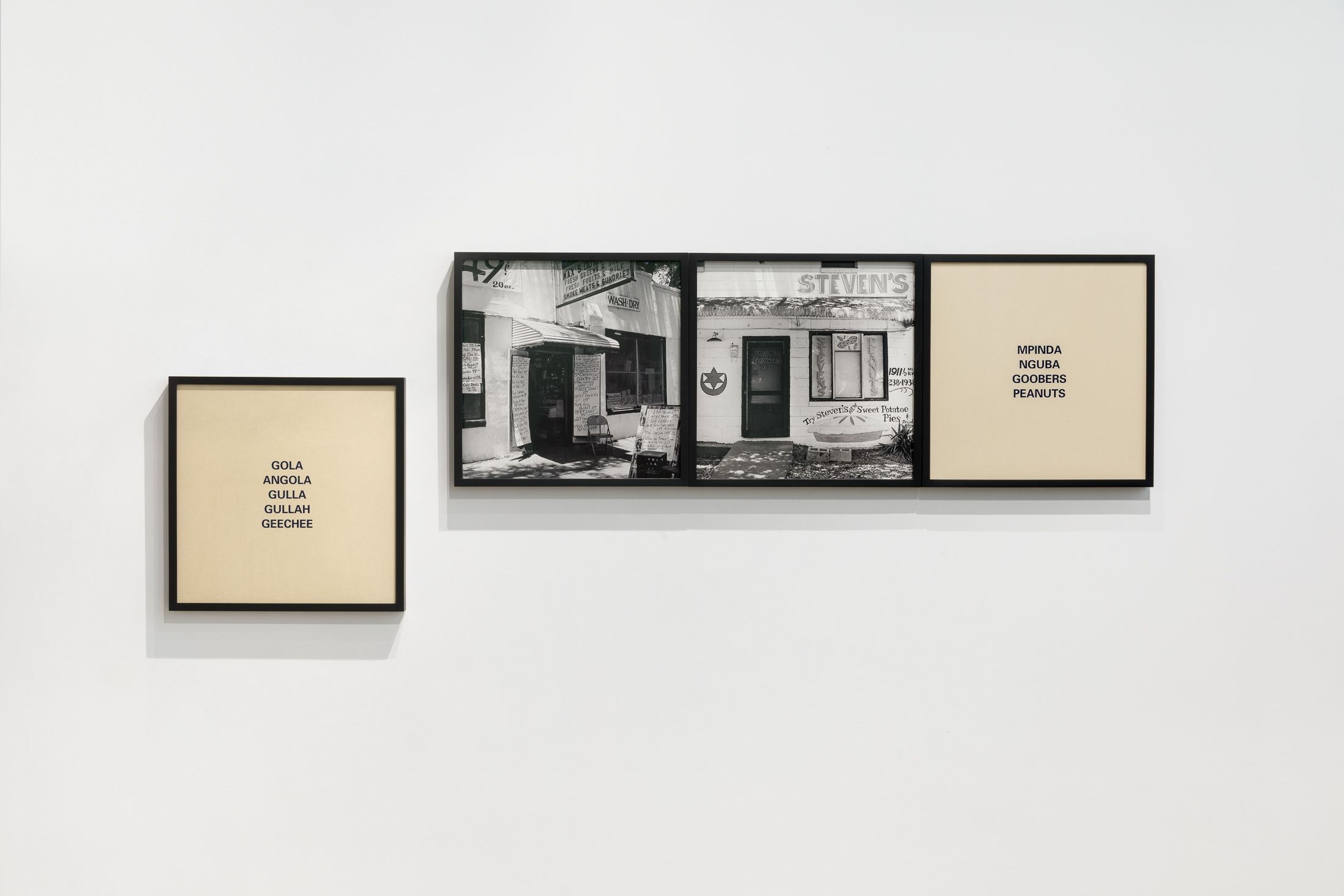

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Peanuts), 1991-1992. Photo by Daniel Pérez, courtesy of Swiss Institute.

-

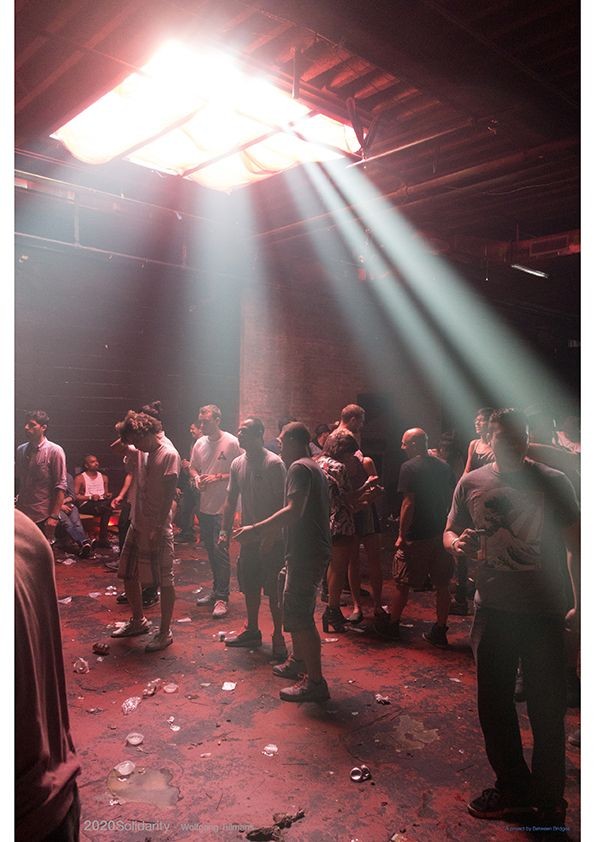

Beneath Tongues, installation view. Photo by Daniel Pérez, courtesy of Swiss Institute.

Every piece on the first floor possesses a distinctly developed visual or auditory language that eloquently enunciates its intent. Sondra Perry’s video hides behind a privacy protecting screen, letting this sense of security shield unspoken words. You can see Title TK 5 if you look at it from the right angle as you walk around the room, but once you directly confront it, you’ll find a looped video of a 3D-rendered mouth. Ideas surrounding technologies of representation and surveillance come to mind before shifting to Steffani Jamison’s Same Time (Seattle 1) and Same Time (Seattle 2). Clear polyester film with gestural black acrylic marks, or glyphs, grazes the wall and then lays atop a slender white platform, the scroll-like shape of the moving glyphs signifying written text. This approach feels distinct from both Carrie Mae Weems and Christine Sun Kim’s works in this exhibition — they both explicitly use English characters and focus on translation. Kim directly translates English into Deaf English in her four charcoal drawings, as the phrase “can’t see a thing” becomes “see zero” and “not gonna repeat myself” transforms into “train gone sorry” in Deaf English. The text in Weems’s suite of gelatin silver print photographs and screen prints touch on the lexicon of Gullah and Geechee, referencing the act of tracing the linguistic evolution of English words back to their African sources.

-

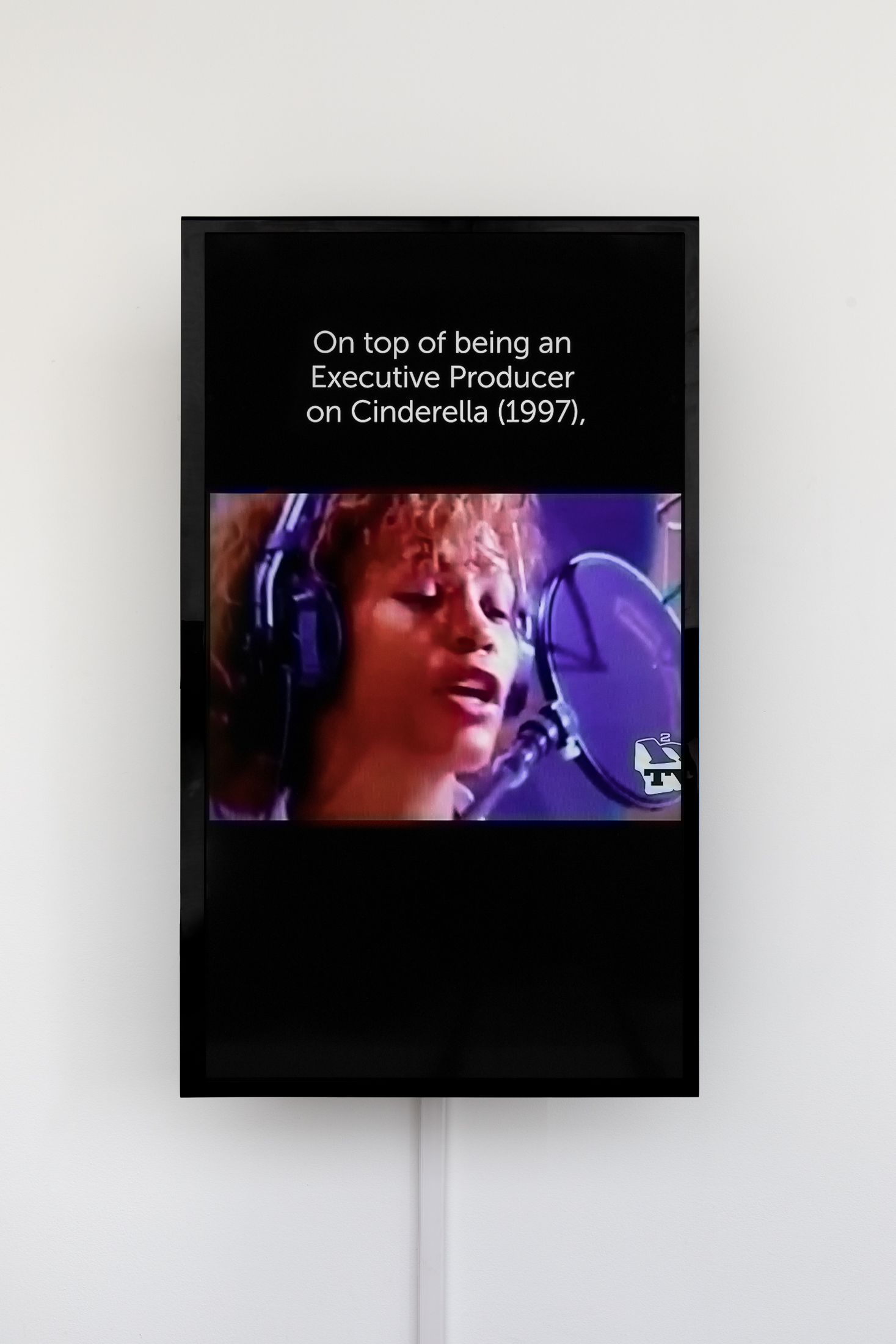

E. Jane, Let’s talk about Whitney Houston’s February 1998 Appearance on The Rosie O’Donnell Show (Part 1), 2022. Photo by Daniel Pérez, courtesy of Swiss Institute.

-

E. Jane, Let’s talk about Whitney Houston’s February 1998 Appearance on The Rosie O’Donnell Show (Part 3), 2022. Photo by Daniel Pérez, courtesy of Swiss Institute.

-

E. Jane, Let’s talk about Whitney Houston’s February 1998 Appearance on The Rosie O’Donnell Show (Part 4), 2022. Photo by Daniel Pérez, courtesy of Swiss Institute.

E. Jane’s annotated video essay, Let’s talk about Whitney Houston’s February 1998 Appearance on The Rosie O’Donnell Show (Part 1), the first piece you see when you walk into the gallery, best illuminates the show’s intentions. In this excerpt of a longer moving image work, E. Jane breaks down the fact that Whitney Houston does not owe anyone her labor, yet she is put in a position where she has to defend her right to rest. A clip of Houston presenting O’Donnell with a sick note from her mother claiming she was too ill to be on the talk show plays, but E. Jane interjects, explaining how Houston’s absence is a form of resistance. The video is cut into three; the clip on the second floor, Part 2, grounds the exhibition and brings forward Elyse Smith’s curatorial objective by focusing on the agency expressed when creating culture distinctly for yourself and your community. Jane emphasizes the fact that Houston describes how long it took for her to produce her version of Cinderella alongside the pitfalls she faced while working on it in this second clip. Houston was steadfast in having the movie done her way. “They (the production company) had other ideas, but I had mine,” she says.

The exhibition is an exercise in listening, one that arises from the intangible architectural framework built around the language of each piece. Before a viewer can begin to interpret this language they need to ask themselves, how do you listen to a work of art? The advent of “listening” to a visual piece is central in theorist Tina Campt’s book Listening to Images, where she focuses on photography concerning Black subjects who are ordinarily dismissed. By forcing counter intuitive thinking, asking people to take themselves out of their normal understanding of terms and practices they regularly participate in, we begin to allow ourselves to encounter images in a way that opens us to uncover alternative ways a work of art can resonate with us. Every work Elyse Smith selected for this exhibition has something to say, but in order to understand the interior rhetoric of what each artist wants to communicate, you need to decipher it yourself.