A FORMAL OCCASION: THE LISBON ARCHITECTURE TRIENNALE

It’s been a year of biennials and triennials: Venice of course, but also the London and Istanbul Design Biennales, as well as the Oslo Architecture Triennale , while last month yet another opened — the Lisbon Architecture Triennale, now in its fourth edition. For André Tavares, co-curator in Portugal with the late Diogo Seixas Lopes, the current glut of biennales and triennales reflects “a moment when magazines — historically a space to consolidate and exchange architectural knowledge — are losing ground to a quicker digital world … What was previously happening in a few places — magazines and schools — is nowadays happening in other places, such as archives, museums, and large-scale events.”

Where Venice was all about social concerns, saving the planet, and general do-gooding, and Oslo about pretty much everything, Lisbon, in marked contrast to its last iteration, sets out to deal with more traditionally architectural matters. Baptized The Form of Form, it’s essentially a triptych, two of whose parts are aimed primarily at architects, while the third achieves broader appeal. Lisbon Triennale president José Mateus summed up the aims of this fourth edition thus: “In the current context of the crisis of the understanding of form, if not a crisis of form itself, and in a reality where the image prevails, it is opportune to pause and to reflect on the reasons for, and the origins of, form.”

For Paris-based Mariabruna Fabrizi and Fosco Lucarelli, founders of Socks Studio, who were responsible for the content of the “title-track” show (like the triennale as a whole it’s baptized The Form of Form), “the expression ‘form of form’ can be about many things, and during the process of organizing this exhibition we started to understand it as the formation of form, something inherently different from formalism.” Fabrizi and Lucarelli describe Socks Studio as “a platform for speculation and discussion” which takes the format of “an expanding visual atlas,” in other words a fascinating online image database of art, architecture, and all sorts of other things that have caught their interest and attention. For their splendid triennale location, on the waterside at Belém, Fabrizi and Lucarelli attempted to reproduce something of the Socks online format by pasting identically sized A4 images — chosen and organized for what they might have to say about form — up onto the walls. Unfortunately, the choice of such a small reproduction scale, and the absence of the explanatory texts that make the database such a joy, render the whole exercise underwhelmingly opaque.

Thankfully, however, the container in which Socks’ images are displayed more than saves the day. It consists in a temporary pavilion, jointly designed by Belgian architects OFFICE (Kersten Geers and David Van Severen), Americans Johnston Marklee, and the Portuguese Nuno Brandão Costa. Thrown together by Seixas and Tavares, the three firms scratched their heads about how to respond to the brief, until one day they struck on the bright idea of combining elements from their own projects to form a new structure, each office choosing buildings from the back catalogue of the others. The resulting cadavre exquis is a delightful capriccio that plays on notions of inside and out, the finished and the incomplete, the abstract and the prosaic. Constructed from white Glasroc sheathing board mounted on a metal frame, it presents the revers du décor to the approaching visitor, and only once within it (“inside” doesn’t seem the right word for a structure that’s largely open to the sky) does one begin to comprehend the forms that have been stitched together Frankenstein’s-monster style. Sudden changes in scale, oddly framed views of the neighboring MAAT building, of the Tagus, or simply of the azure Lisbon sky, as well as curious interstices, junctions, and disjunctions, are among the seductive tricks deployed by this myriad maze of pure space, which is also a paradoxical exercise in both formalism and immateriality.

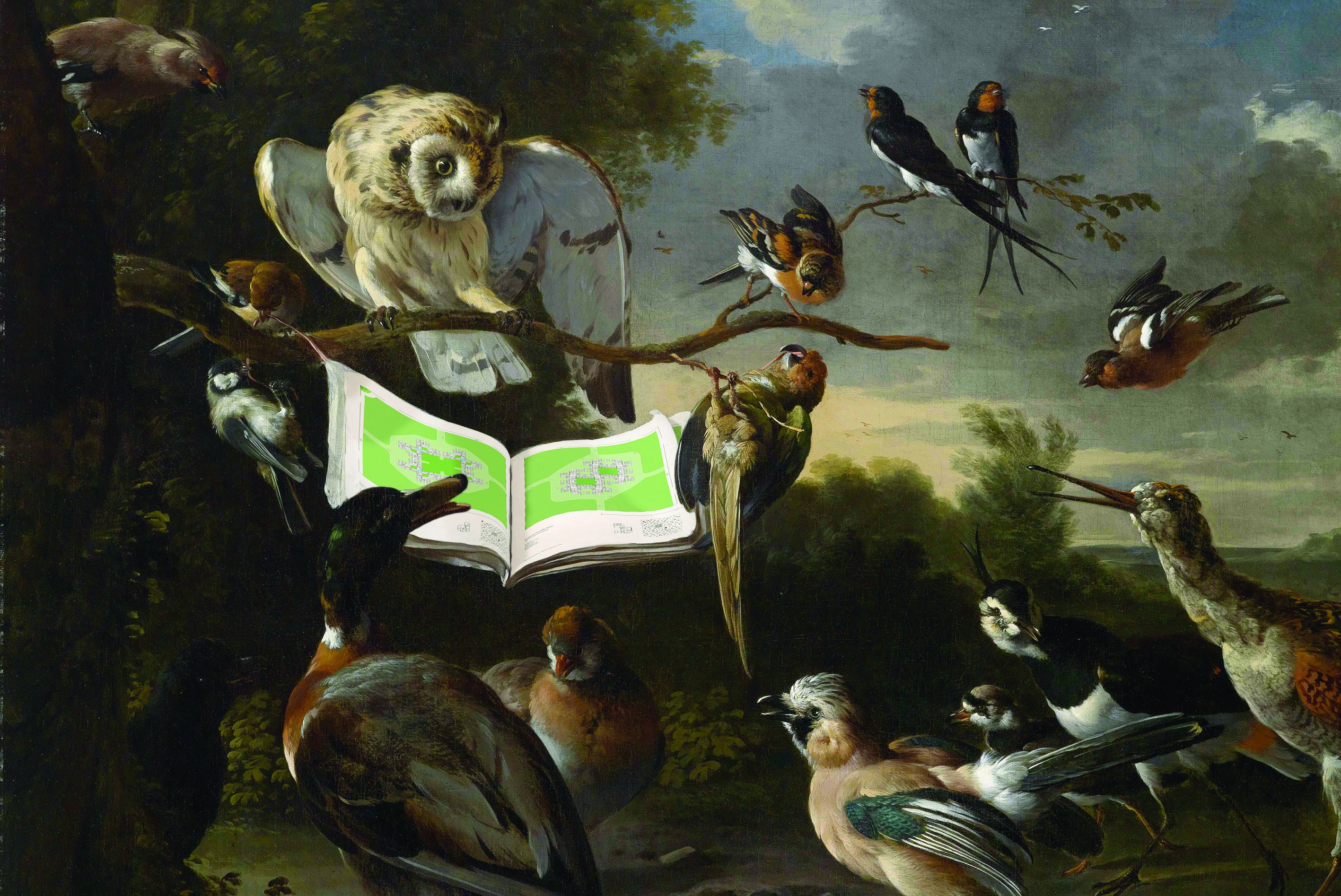

A short walk away, in the Garagem Sul of the Centro Cultural de Belém, is the second exhibition in the triptych, The World in Our Eyes. Curated by FIG Projects (Fabrizio Gallanti and Francisca Insulza), it sets out to explore the ways architects apprehend and represent the world in which they live and operate. Perhaps Tavares’s comment about biennials and triennials taking over from magazines was interpreted a little too literally here, for this very dense show, awash with text and images, frequently seems like pages from a specialist review that have been stuck up on the wall (a perennial problem, it must be said, of exhibitions about architecture). For their contribution, AA Diploma Unit 14 decided to be totally upfront and honest about this by simply presenting a large-format book set down on a podium. The advantage of a book is that you can easily zoom in and out on the bits that interest you, whereas some of the displays in The World in Our Eyes feature tiny text and images displayed so high up they become very hard to decipher (at any rate for this pair of tired old eyes). Which is a great pity, because many of the studies are genuinely fascinating. Highlights include Interboro Partners’ The Arsenal of Inclusion and Exclusion — “101 ‘weapons’ that architects, planners, policy-makers, developers, real estate brokers, community activists, and other urban agents use to restrict or promote access to the space of the city,” presented as a giant eagle’s-eye cartoon —, exhaustive compendiums of anonymous, everyday typologies put together by two groups from Switzerland (Christ & Gantenbein, and Laurent Stalder, Elke Beyer, Kim Förster, and Anke Hagemann), as well as Keith Krumwiede’s witty Freedomland, “a work of architectural satire” that seductively sells “a bastard lovechild” of a city masterplan through the (mis)appropriation of celebrated historical paintings.

While the first section of the triptych paid homage to pure form, and the second paid perhaps too little attention to the form in which its content was delivered, the third, titled Building Site, achieved just the right balance between form and subject matter. Curated by Tavares, and displayed in the delightful 1960s period piece that is the Gulbenkian Foundation (whose exquisite interiors are by Daciano da Costa), it was the show with by far the broadest appeal, managing the feat of accessibility to the layman without in the least dumbing down or simplifying. It also splendidly side-stepped the “book on the wall” trap with a perfectly judged mix of objects, artifacts, models, texts, images, films, artworks, and even children’s cartoons. The basic subject was how architectural form takes shape in the construction process, that heroic, fleeting, dangerous, unpredictable, collective moment that transforms abstract ideas and marks on paper (or digital data) into a solid, corporeal, material building. Spanning the last 120 years, it opened with Cedric Price’s exhaustive and inventive 1970s attempts to render the British construction industry safer and more productive, took in Brazilian coop schemes where design is determined by a light brick module that can easily be carried by the future occupants, who will construct the apartment buildings themselves, and climaxed with a juxtaposition of 1930s-American and postwar-Soviet children’s cartoons, in which the ideology of construction came to the fore (the steel I beam in the interwar U.S. unleashing the chaotic forces of capitalism, versus the concrete panel of Khrushchev’s Russia, base element of the happy collective tomorrow). On the way we saw how François Hennebique created an empire of reinforced-concrete construction through clever division of labor, as well as the architectural implications of European Capital of Culture designations, which not only inspire new construction but can also shape it through their deadlines — OMA’s forms for Porto’s Casa da Musica were largely determined by an absurdly optimistic two-year calendar, which led to construction being started before the design had even been finalized. Which goes to show just how different indeed are the formation of form and formalism, the real world being shaped by forces far more powerful than any architect’s volition or ego. Eat your heart out Ayn Rand!