INTERVIEW: Odile Decq on Risk-taking, Rule Bending, and Gender Constraints

In the stifling quiet of a Parisian August, at the end of a courtyard in the historic Marais neighborhood, the Goth-rock blare of The Sisters of Mercy lacerates the hush. The sonic blast is coming from the offices of French architect Odile Decq, a rock star of sorts in her field, known for her I’m-with-the-band allure — a Siouxsie Sioux redux of heavily kohl-rimmed eyes, teased black tresses, and sculptural rings on every finger. But behind the mosh-pit appearance hides a pragmatic optimist who, for the past 31 years, has been the principal of ODBC, the now XX-strong architecture firm she co-founded with her late partner Benoît Cornette. Winner of the 1996 Venice Architecture Biennale, Decq has taught several generations of students at universities around the world, including the renowned Ecole Spéciale d’Architecture (ESA) in Paris, which she now directs. But it wasn't until recently that her work began to reach a wider public through her ever-more prestigious architectural realizations, which include the Museo d’Arte Contemporanea di Roma (MACRO, 2001–10), the FRAC Bretagne in Rennes (due to open next year), and the just-completed Phantom restaurant, located in one of France’s most prized national treasures, the Opéra Garnier. At the age of 56, Odile Decq has every reason to turn up the volume.

Aurélien Gillier: Throughout your career you’ve worked in so many different fields: as a teacher, as the director of ESA, making art installations, creating stage design, and in recent years building large-scale architecture projects. How do you define yourself socially?

Odile Decq: I don’t define myself, I’m an architect!

Have you ever been asked whether you were an interior designer or a “real” architect?

I haven’t heard that question in a long time. Nobody asks me that anymore. But it could easily come back. It’s a question that girls are automatically asked. I’ve been practicing for 30 years and I’ve been hearing that for 30 years. I’m not a militant feminist, but I’m fed up with frequently being taken for a feminist spokesperson, and of people asking me this kind of question in full knowledge of the insinuations behind it. It’s very tiresome!

Do you think that like Denise Scott Brown in her 1975 essay “Room at the Top? Sexism and the Star System in Architecture,” you could take a vocal stand on the condition of women architects?

I don’t know this text, but it seems to me it’s not a question of campaigning for the condition of women but rather of affirming that it’s possible to be a woman, an architect, and respected, even though there still aren’t many of us.

Don’t you think the trend is evolving, especially in architecture schools where the ratio of boys to girls has changed?

The trend has evolved and that’s all! If you look at registrations with the French National Order of Architects, when I started we were 11% and now we’re still only 30%.

With regard to the position of architect, is it not an advantage to be a woman?

It has advantages and disadvantages. Where the advantages are concerned, when you’re on site with a bunch of guys in front of you, I always say to my female colleagues that there’s no point yelling to get yourself heard, given that their voices would become too shrill and they’d just seem ridiculous. It’s better to say things firmly, keeping your voice down, and with a big smile. In architectural practices, it’s the women who are sent on site because everyone knows things will go differently. We’re always asked about this, the proof is that you yourself began with this subject.

Sorry to contradict you, but actually it was you who brought up the subject of women architects!

Oh I’m sorry! (Laughs.) I’m probably used to always hearing the same questions because with the way I look people often don’t think I’m an architect.

I’ve read all sorts of things about your look: sometimes you’re labeled a Goth, sometimes a Punk, and I’ve also heard you described as a female Robert Smith.

I’m more Siouxsie and the Banshees than Robert Smith! (Laughs.) But overall I would probably say that my look is more Goth than Punk, even if Goth came out of Punk. The group I was always most into is The Sisters of Mercy.

Would you say the look is a creation, or even an extension, of your architectural persona?

I’d never asked myself the question in that way. I just sort of fell into this look one day. It’s actually done me rather a disservice since people imagine all sorts of things about me — that I’m not serious, or I must be a weirdo. But first and foremost it’s a kind of armor, a way of protecting myself vis-à-vis the people I meet. It makes some people suspicious and you feel that straight away. I never go any further with them because I know from experience that nothing interesting can happen with people who can’t get past the barrier of prejudice. But most of the time I totally forget I’m like that!

You only wear black. Is this a rejection of optimism?

I started wearing black during my studies before every other architect started wearing it. With dyed-blond hair, I wore black leather pants for their rebellious connotations. At the beginning, it wasn’t about a particular color, but little by little it became an addiction. And it’s a serious addiction!

Has this addiction also infiltrated your architecture?

It’s fairly recent. At the beginning, I never wanted to impose on others what I did for myself. When I won competitions, people were afraid I’d give them too much black. But attitudes seem to have changed now, people know about black in my work.

Also, your addiction to black is clearly evolving — at the MACRO you use a lot of red too. The area in Rome where the museum is located is a fairly strictly protected neighborhood. Were there particular issues concerning the preservation of the historic fabric?

Not really, apart from the façades and a little bit of the structure which we had to keep. But what might seem like an obligation is actually what has allowed contemporary architecture to exist in Rome — behind the façades we could do almost anything. That certainly wasn’t the case for Phantom at the Opéra Garnier.

So how do you manage to take architectural risks when dealing with an icon like the Opéra Garnier?

Well to begin with you must always fully understand the constraints. At the Opéra Garnier, we weren’t allowed to touch the façades, the pillars, or the vault. We nonetheless had to enclose the restaurant because the original space was open, all the while making sure not to create “windows,” which was something the Ministry of Culture didn’t want. My first idea was to create a sort of glass undulation behind the pillars; as we went forward with the project we continued this undulation round the entire perimeter because this undulating screen responded to the questions and restrictions set by the clients. The architect in charge of the building’s conservation was supportive of the idea of introducing contemporary architecture within the confines of the Opéra. But when I went to present my scheme to the relevant architect of the Bâtiments de France (an organization of the French state that acts as architectural-heritage inspector), he insisted on pointing out to me that the project was to be inserted into Charles Garnier’s opera, a historic monument that had never been in any way modified since its creation, and asked me if I really understood what I was doing… But then, after we’d presented our scheme to an important committee, we were told it constituted an exemplary project that could now be submitted to the National Committee for Historic Monuments. We subsequently appeared before them, and they unanimously accepted our proposals.

Without the constraints imposed on you at the Opéra, I imagine your project would have been quite different?

I really couldn’t say. You know, as an architect you always respond to a brief with constraints. We’re not like artists. An artist’s work is a response to what he or she wants to do, whereas an architect has to respond to a specific program with all its restrictions.

What’s your opinion of contemporary architecture in Paris?

I think it could take more risks! When I began studying at architecture school, everyone said that 19th-century architecture was horrible, that we should think and build modern. And then at the end of my studies, it was the beginning of Postmodernism where people began to reconsider 19th-century architecture. But today I think we’ve come to over-fetishize the 19th century and Haussmann’s Paris. As a result, it controls anything and everything, and Paris is turning into a museum. When people talk about skyscrapers in Paris, it sparks a huge debate, and we do small projects on the city’s periphery, without in any way sorting out the status of central Paris. A project like the Centre Pompidou could never happen in Paris today.

Odile on her chair design for the restaurant in Rome's MACRO, "It's actually quite simple. It consists of 2 squares and just a crease in the back gives it an interesting note and more structure," in a profile by Euromaxx.

Isn’t it also a question of political drive? For example, the Centre Pompidou would never have seen the light of day without the tenacity, authority, and persuasive force of Georges Pompidou.

Yes, but that isn’t the case anymore today. On the one hand there’s no money left in the public sector, and then the kind of projects Sarkozy gave his backing to were the renovation of the Grand Palais, the creation of the Museum of the History of France, and the fiasco that was “Grand Paris” (a debate about an urban renewal plan for Greater Paris), which never went any further than the initial hype. All this ballyhoo to produce next to nothing — a new transport plan, an underground rollercoaster, for 32 billion euros — it’s unbelievable! There’s no vision or ambition anymore, no real will to change and reorganize the city.

And what do you think of Carla Bruni-Sarkozy?

Apart from the fact she dresses like Jackie Kennedy, I’ve nothing to say about her. I don’t know her and she doesn’t interest me as a singer. I frequently travel to Italy, she’s Italian, and Italians hate her.

And her role as France’s first lady?

This isn’t a kingdom for goodness’ sake!

Are you so sure?

Actually yes, we do live in a kingdom. In France, there is a sort of royal court and a lot of architects think that you need to go get your handout from the king or those who administer power on his behalf. For example, when you’re planning to go abroad to do something — be it an architectural, artistic, or other project — your natural reflex is to go to the city, the region, or the government to ask for their financial or political help, because there’s a belief that the state can always give you the aid you need to leave. Whereas I think that we’re quite capable of getting what we need without asking the state. And with this system of handouts you’re dependent on those who supply the money, you can no longer really do what you want, and you’re less free to say what you feel. I’m not interested in that.

You say that even though you’ve worked on a majority of public projects?

I have absolutely no problem with that: I won the competitions and completed the buildings, and I don’t feel I owe anyone anything. I’ve always wanted to remain free. But at the same time, I’m not going to bite that hand that feeds me!

You also work a lot abroad. I imagine that helps one to be less subservient?

Yes. My survival comes from abroad. I’ve always traveled to give lectures and teach in foreign architecture schools — I love doing it and it comes easily to me. When I started out I would give lectures abroad without even being paid, which I didn’t mind because I found it was necessary. I was often asked for names of other French architects, but they would always set too many conditions: they wanted to be paid and to travel in business class, and in the end, they weren’t invited to give talks. When you’re starting out you have to be prepared to make concessions.

Where have you taught?

I’ve taught at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, at the Architectural Association in London, at Columbia University in New York, and I’ve led workshops at SCI-Arc in Los Angeles.

Is that how one becomes director of the École Spéciale d’Architecture?

No, not at all. One becomes director to a certain extent because one teaches there. ESA is a partnership which elects its director from among candidates who are, for the most part, teachers at the school.

What makes the École Spéciale so special?

It’s a private school which answers to no ministry or bureaucracy, so it’s outside of the system and can therefore be more free. We’re also very internationally minded. English and French intermix and lectures in English are not translated, which would be unthinkable in all the other French architecture schools which are state-financed. Moreover, ESA adheres to no particular trend — we’re open to all of them. Our teachers are all very different, but young and dynamic, like Cédric Libert, Thomas Raynaud, Jean-Christophe Quinton, Reza Azard, or the artist Simon Boudvin.

Does Peter Cook also qualify as a young and dynamic teacher?

No, but Peter Cook is such a major figure — an institution! When I heard he was going to have to retire as director of the Bartlett School of Architecture, I asked him if he wouldn’t like to come and teach at ESA. And we’ve managed to hang on to him ever since. We weathered a bit of criticism about his being past retirement age, but let’s be serious: does someone like Peter Cook ever retire? He’s still taking on architectural projects, he’s building an architecture school in Australia, a library in Vienna, and other projects in Spain. I’ve never seen anyone with such a full travel schedule. And he’s 73!

You live in Paris. What does your home look like?

It’s a large apartment that will never really be finished. It’s rather camping de luxe! (Laughs.) I think most architects’ places are never finished. That’s the difference between architects and their clients. People are afraid of construction work, they prefer to buy apartments that are finished. Only architects will move into a half-finished apartment. I know plenty who’ve only got half a bathroom, and in my place, the wiring isn’t finished.

Is it your tendency never to finish things?

No, don’t be silly! I finish jobs for other people! (Laughs.) My place isn’t finished firstly because I moved in when the work wasn’t completed and then, as time went on, I realized I could live with it, and now I don’t have the time to sort it out. I admit it can sometimes be a pain. When I come home in the evening it would sometimes be nice to walk into a completed apartment. Even people who come to visit will say, “Ah! There’s still no sink in the kitchen,” and then I’ll tell them that I’m “going to the well” when I need water because the only faucet is in the bathroom. But what do I need a kitchen sink for when I’ve got a dishwasher? (Laughs.)

Is this lifestyle also a part of your penchant for risk-taking?

I think the idea of risk-taking and responsibility hardly exists anymore. It reminds me of an article I read about a survey at Harvard which showed that over 70% of the students didn’t want to become managers. Today’s youth is so afraid of tomorrow that they don’t even dare invent the future. To invent the future, you have to dream it. Many of them think that everything’s already screwed, that the future will be worse, and that the planet will be destroyed. I think that on the contrary, it’s in our time that we can still make change happen. The best examples right now are in Tunisia and Egypt, even if we don’t know what these revolutions will lead to.

So, could one say the French Islamic-veil law is an example of risk-taking, even if ill-advised?

I think the worst laws that have been introduced here are those concerning the precautionary principle, which kills risk-taking. It’s terrible because it impedes society, it impedes thought, it impedes everything! I see it all the time in my profession: if something isn’t expressly allowed by law then on principle it’s forbidden. I think it’s the greatest danger threatening our society.

Because it leaves no room for the unpredictable?

Yes, exactly. Creation happens because it’s unpredictable. It’s like with scientific discoveries: many of them weren’t at all foreseen and in fact, were complete accidents. You have to leave space for the unforeseen.

But you also have to find the kind of clients who are willing to take risks with you.

You have to adapt the risk-taking to the client, but you must always take him or her further than they imagined. The client’s limits are those of his or her imagination, while the architect’s role widens the field of possibilities, and therefore you need to educate the client in order to take him or her further. It’s the same as with teaching when you get students to see that they can go much further than they thought they were capable of. And that’s a great joy! Everything in life is like that — discovering that nothing’s impossible.

Are you not at all worried about the current economic climate?

I’ve had problems before, and have already been through several lean periods where I had to scale down my team. You say to yourself that you’re not condemned to practice only architecture, you accept other jobs, you take on projects in design, and you enter lots of competitions. That’s how I won the commission for the MACRO in Rome. I’m not worried because I find it serves no purpose. I know how to adapt to all sorts of conditions.

Aurélien Gillier is a Paris-based freelance architecture journalist and graphic designer, as well as a co-founder of the architectural periodical Face B. The interview was translated from French by Andrew Ayers.

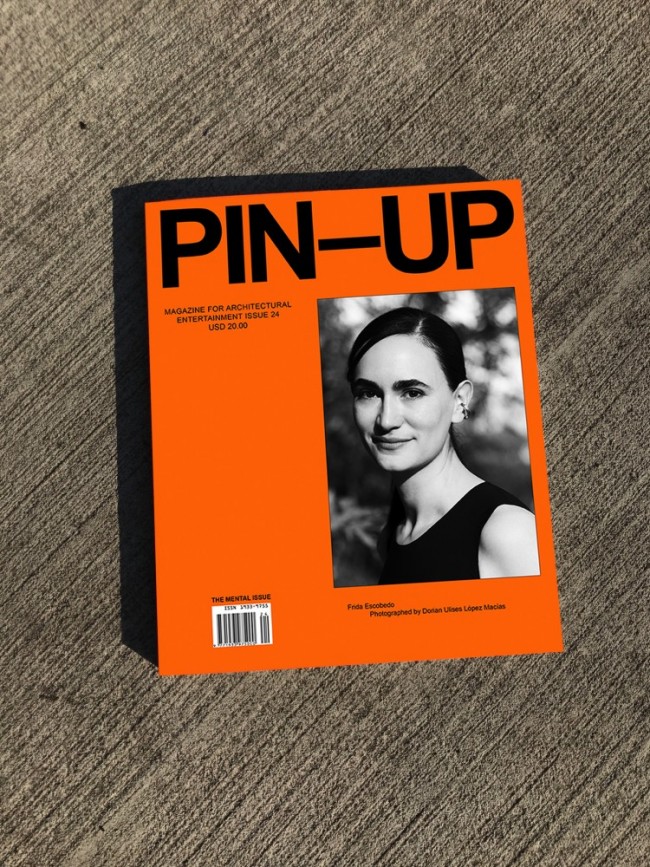

Taken from PIN–UP 11, Fall Winter 2011/12.

Text by Aurélien Gillier.

Photography by Katja Rahlwes.

Translated from French by Andrew Ayers.