INTERVIEW: The Artist Joep van Lieshout about Utopia, Dystopia, and HIS DESIGN FOR A NEW CHAISE LONGUE

Joep van Lieshout is no stranger to controversy. The 55-year-old Dutch artist, who’s been active under the name Atelier Van Lieshout (AVL) since 1995, most recently made waves with his Domestikator (2015) — a nearly 40-foot-tall structure that many said appeared as two buildings having sex. In 2017, when it was due to be unveiled during FIAC in Tuileries Garden, the Louvre banned it; the Pompidou, apparently less prudish, displayed it instead. This irreverence and incessant clashing with accepted social norms defines much of van Lieshout’s oeuvre. Working across art, architecture, and design, van Lieshout challenges the world at large not merely by countering and eschewing social mores, but by making whole new worlds. Case in point: his SlaveCity, a project he had begun in 2005, presented a cradle-to-cradle fully sustainable political and economic model. Of course, this was only realized through the city’s some 200,0000 slave-citizens working seven unpaid hours a day at a call center (the surplus value generated from them meticulously calculated by van Lieshout). These Aldous Huxley-esque realities comprise all manner of objects. There are drawings, sculptures, functioning blast furnaces, furniture — the last of which has recently leapt from one-off sculpture to a market-ready design object called Liberty Lounger. Derived from a design created as part his project New Tribal Labyrinth (2010–ongoing), it is now available in solid walnut thanks to the Dutch design company Moooi, who presented it for the first time during this year’s Salone del Mobile. PIN–UP caught up with the self-described enfant terrible about design, world-building, and, of course, liberty.

Can you give me some background on the Liberty Lounger? How does it fit into the larger context of your work?

After SlaveCity, I started a project called New Tribal Labyrinth, which is a future, utopian society in which people live together in tribes and dedicate their lives to one certain thing. It could be the production of steel, writing, whatever. I wanted to do a reinvention of the industrial revolution — to go back to the origin of our wealth, of our culture. The origin of design as well. The origin of materials. I imagine this tribe that would work in the spaces I built. There’s lots of manual labor; it’s very hot, very dusty, but they also live there, so there’s kitchens and bathrooms and everything inside.

Did people actually live in the New Tribal Labyrinth?

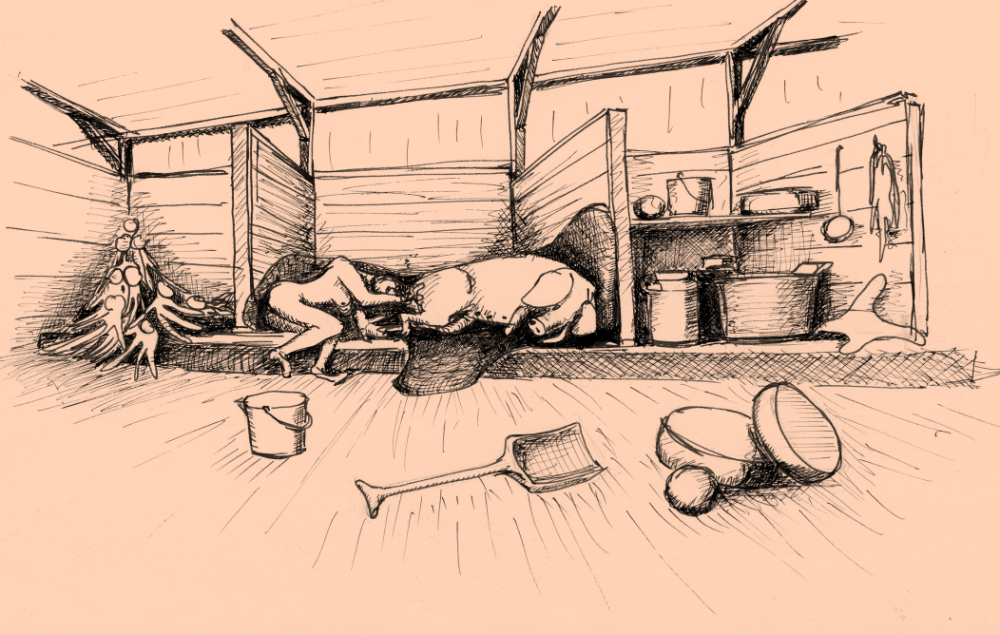

No. It’s just a sculpture. There’s a sawmill (first displayed at Amsterdam’s GRIMM Frans Halsstraat gallery as Manufactuur (2012)), which is very important; it was the origin of the Liberty Lounger. It’s powered by a treadmill where you can walk around 16 girls or men or whatever. You can cut planks or beams, and with the planks and beams, you can build all the buildings and furniture, so you can create your world. But this has a very strange mixture between utopia and dystopia.

Is it punishment or is it like sport schools? Or is it renewable energy?

Renewable, but also you become very strong all together. There is a kitchen, so the cooking and the building, the eating and the working all become one. There’s a sawmill and people need to sit, and so I created this furniture.

Did you create the furniture with the sawmill yourself?

No. It could have been done, but it would’ve taken 16 people to power it and just a lot of work.

What other kind of furniture did you make for New Tribal Labyrinth?

I needed furniture for the living space, and I wanted it to be very elemental, very sculptural. So, I made super simple sketches, and then without the use of any measuring tape or angles, I just started making it like — pah pah pah — very fast. And the idea is that I had to finish within one day. If you don’t finish it in one day, from design to finished product, it’s a bad design. It’s a failure. If you cannot make it good in one sitting, then why make it?

-

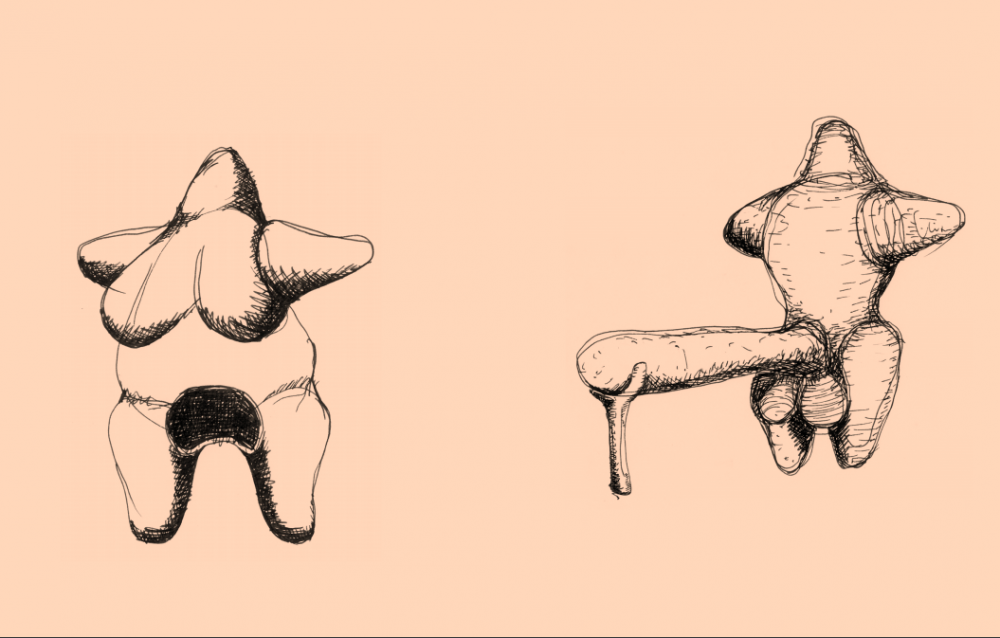

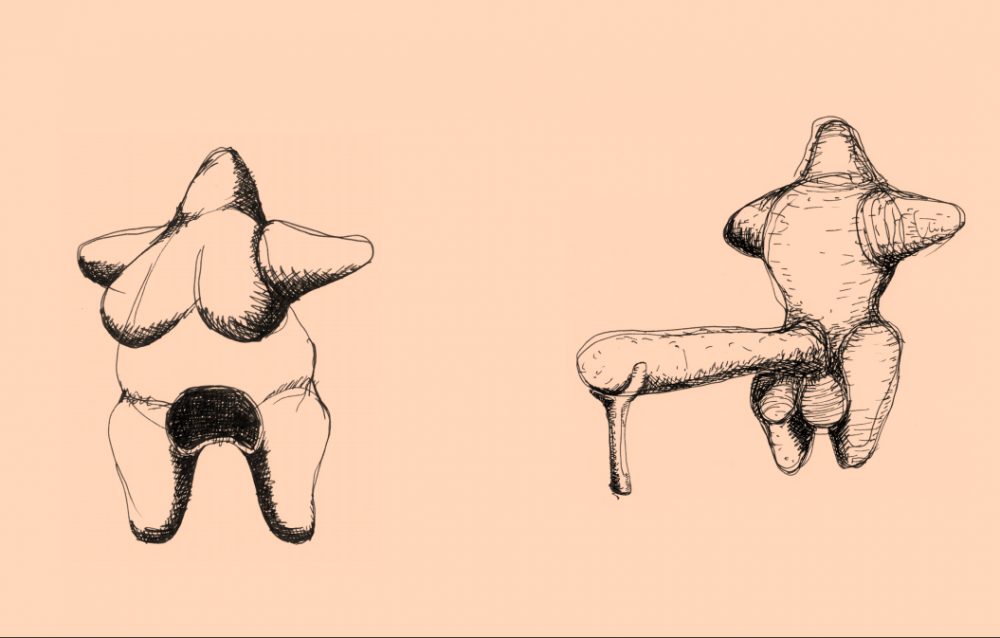

Drawing from New Tribal Labyrinth (2012) by Atelier van Lieshout.

-

Saw Mill at GRIMM Gallery (2012), Atelier van Lieshout. Photo by GJ van Rooij.

-

Prototypes by Atelier van Lieshout (2012). Photo by Atelier van Lieshout. In the center of the top row a predecessor to van Lieshout's Liberty Lounger, in white.

Why did you impose this one-day limit on yourself?

New Tribal Labyrinth is like the Arts and Crafts movement, which at that time was trying to protect the arts and crafts from industry, except in this case it’s trying to protect industry from the arts and crafts. Industry is disappearing. Industry is going to faraway countries, and here, you and me, we work as technocrats or bureaucrats, as lifestyle victims. What I see a lot in design is that there is an extreme distance between who makes it, produces it, and buys it. I thought there’s a counter-reaction to making something which is designed and produced and sold by the same person. But I’m not a designer; I’m a bad carpenter. I thought let’s just make a chair and that’s it. It’s a kind of a protest against the way new technologies create alienation between offered products (and their producers and consumers).

I’m assuming in the case of the Liberty Lounger for Moooi that it’s not just bad carpentry?

No, it’s supposed to be bad carpentry, but they’re incapable of doing that.

How did the name come about?

The original Liberty Lounger I designed for New Tribal Labyrinth is really built out of 2x4s and long screws and plywood. At the end of the day, when I finish the sculptures, I take a spray paint, whichever I think would fit with the piece, and the color for this one was “liberty.” It could also be “chestnut” or “Capri” or “banana,” but this one was called “liberty.” All the pieces have the name of the color of the spray can.

Liberty Lounger by Atelier Van Lieshout for Moooi (2018). Image courtesy Moooi.

In your world, similar to our own, there seems to be a great deal of hardship and suffering — but also efficiency and environmental sustainability and certain new liberties. What kind of lives do you want people to live?

Of course, I like people to be happy and to fulfill their needs and their desires. On the other hand, I also think it’s kind of idealized that more is better or more people is better. I think that we are asking a lot of our planet — with resources and energy and pollution and things like that, it’s really too much. I don’t suggest we start killing 50% of the population, but that we be sensitive about it. Imagine you’re 70 years old. You don’t work anymore. I think everyone should have the choice, “Do I want to live 20 more years, costing a lot of money to society, to my children, become senile and things like that?” Or say, “Okay, I’ll stop now, I worked my whole life, if I decide to stop now instead of in ten years’ time, I save the community 4 million dollars. You know what, give me the 2 million for my children and I’ll go away now.” I think that sounds good. Why not?

That can easily turn bad.

Yeah, “Mom sign here! Now!” But on the other hand, I think there’s this kind of hypocrisy now. There’s still people against euthanasia or abortion. I think that everyone should have the total freedom to decide about their own life.

-

Drawing from New Tribal Labyrinth (2012) by Atelier van Lieshout.

-

Atelier van Lieshout, Everyone's Plough, (2012); Metal, wood.

-

Drawing from New Tribal Labyrinth (2012) by Atelier van Lieshout.

-

Atelier van Lieshout, La Machine Celibataire (2012); Metal, wood, rope.

So, your worlds are about freedom?

Yes. Well, they’re about freedom and also about restrictions. Not only freedom, because I’m also part of society and I like to be constructive and to make a better world. So, on one hand, I have to fit in the world and all these regulations, and on the other hand, I want to be free.

What kind of world are you trying to make, in general? What do you want for the worlds you make?

I don’t create my worlds to become reality. Utopia, dystopia, the romanticism and the harshness — they all mix. The goal of my work is to be a catalyst for thinking. It’s communication. But in general, I would like to have a world which is a little bit more extreme. A little bit more like New Tribal Labyrinth. I guess I could never become a politician.

Text by Drew Zeiba.