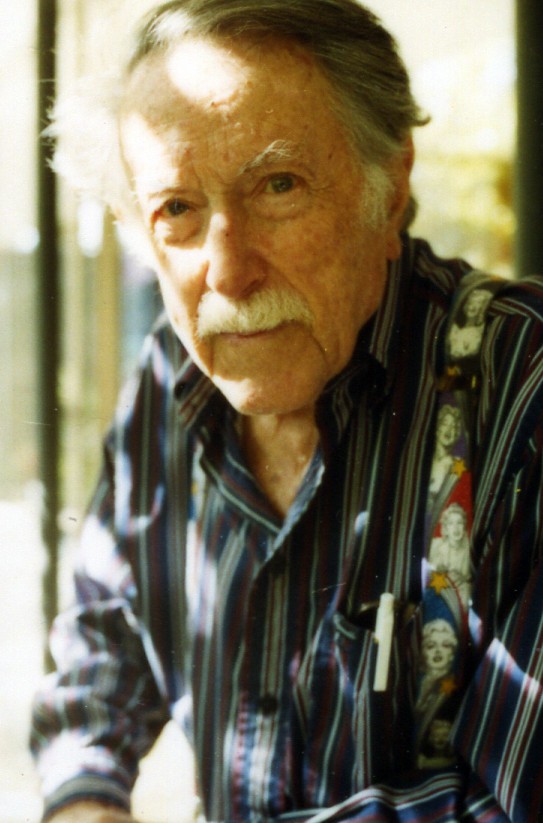

The Malibu Estate of Mr. and Mrs. Eric Lloyd Wright

Eric Lloyd Wright’s house in the Malibu hills, photographed by Todd Cole for PIN–UP.

“We started this in 1986 and have been working on it ever since,” replies architect Eric Lloyd Wright — grandson of you-guessed-who — when asked about his yet-to-be-completed house in California’s Malibu hills. Wright slowly moves his tall body around his studio, and one wonders what’s driving a distinguished gentleman of 79 years to be still in the midst of a construction site. Together with his wife, Mary, who is a watercolorist, Wright has been living for 20 years right next to their future house in almost Spartan circumstances — “We’re in a trailer here,” he explains in his gentle voice — a wonderful understatement in an era when the general public expects architects to be global jet-setters, flying first class from project to project.

Eric Lloyd Wright’s house in the Malibu hills, photographed by Todd Cole for PIN–UP.

Wright inherited the spectacular site from his father, the Los Angeles-based architect Lloyd Wright, who purchased the land in the 1950s when Eric was living and working with his famous grandfather in Taliesin. Although Eric’s father always planned to build a house and live on the land, he never got around to doing so. In 1981, when Eric took over his father’s firm, he quickly realized that “things were not moving, and the only way they were going to was if I went up there and lived on the land.” It was the choice of a lifetime.

Sitting 2,000 feet up on the summit of Malibu’s dry hillscape, the construction site commands the coastline of dense architectural excess, allowing for dramatic views over the Pacific Ocean below. Wright always wanted his “house to grow out of the hill rather than sitting on top of it like a cap. I wanted it to be part of it... like hair.” He laughs when telling the story of how the first time he inspected the site, he finally understood the Chinese adage that if you build on the top of a hill, the gods will not be pleased: “There is tremendous wind in the winter blowing across here. You can have a wind that almost blows you away, something you don’t realize when you’re building on the side of a hill.”

Eric Lloyd Wright’s house in the Malibu hills, photographed by Todd Cole for PIN–UP.

Over the past two decades Wright has been building the house himself, with his staff of six, and only gets experts involved when absolutely necessary. “A couple of years ago I ran out of funds, and since then I’ve only been working on the house when I have the money.” But he continues patiently with what will one day be possibly the most important building of his career: the one that knew no compromises. He smiles at the reality of being one’s own client: “Sometimes, things I wouldn’t do for clients — because I knew they were too expensive — I attempt here.”

Decades before today’s “green” hype, Wright, who has built a reputation in California for sustainable buildings, decided to make this an exemplary project by designing it as a passive solar building. “We have an impressive thermal mass because we’re building it (entirely) with concrete, so we try to do as much of the conditioning of the air and the lighting of the house as we can naturally, without having to use artificial means.” A railing that wraps around the house will be covered in solar panels, and Wright’s drawings — all done by hand — show how steel blades along the facade will form a louvered canopy, which can be opened in winter to bring sunlight into the house, and closed in summer to keep it out.

Eric Lloyd Wright’s house in the Malibu hills, photographed by Todd Cole for PIN–UP.

“As an architect you are shaping the environment that people are living and working in; they’re playing in it, learning in it; they sleep there, they make love there,” says Wright. “But that is also one of the great problems we have in this country — we don’t take education seriously enough.” His belief in the inadequacy of the US educational system has meant that he has always wanted to design a grammar school. “Children in that age group are absorbing a lot of information, but it is mostly wrong. There’s plenty of time to read and write later on. But there isn’t a lot of time to develop your creativity.” And exploring new ideas and developing potential is what Wright is using his house for pending its completion: he runs workshops on solar energy, perma-culture, and bamboo in it, while his wife organizes artists’ workshops.

Eric Lloyd Wright’s house in the Malibu hills, photographed by Todd Cole for PIN–UP.

“Since we don’t yet have any interior partitions upstairs, we have a large space where we can seat 60 people,” he explains. The Wrights always try to make sure that half their participants are from inner-city schools in Los Angeles, in the hope of encouraging future generations to become more involved in society. “Most people these days are spectators, and they don’t care much for design. Unsurprisingly!... Architecture today is more for effect and most architects just want to create a major ‘wow’ statement — to be unique is the most important thing to them. But to be really original is a rare thing.”

Eric Lloyd Wright’s house in the Malibu hills, photographed by Todd Cole for PIN–UP.

Of course there is always the temptation to look for references in the work of his grandfather (whose legacy is celebrated this year on the 50th anniversary of his death). And indeed the “young” Wright doesn’t shy away from making direct comparisons, but is also quick to add that he doesn’t “imitate stylistically what my father or grandfather did. The house really has to stand on its own.” And despite its unfinished state, it already has a strong presence. But will it ever be completed, and does Wright believe that he will ever live in it? After a lengthy pause he collects his thoughts: “Actually, I’m becoming more edgy about not moving forward. It’s bothering me now more than it used to — I feel that I have to do it. I want to see it complete now.”

Text by David van der Leer.

All photography by Todd Cole for PIN–UP.

Originally published in PIN–UP 6.