F-Architecture and the Hymen Industrial Complex

Rosana Elkhatib, Gabrielle Printz, and Virginia Black, the practitioners behind f-architecture, bill their project as a feminist architecture collective (hence the f), but that phrase’s concision may be a bit too restrictive. The three elude neat categorization, working on terms all their own, not just as architects, but also as ethnographers, curators, and designers, disentangling the space and politics that police our bodies. After road-tripping along the southern border of the U.S. to map the agents and architecture of immigration processing; partnering with Ecuadorian cultural and midwifery center AMUPAKIN to stage the achimamas (midwives) and their politics at UN-Habitat; and organizing a legal Arab gay pride parade of sorts, in Amman, Jordan; the trio have now turned their attention to the fake hymen industry. An ongoing subject of interest, their most recent exploration took the shape of Cosmo-Clinical Interiors of Beirut at VI PER Gallery in Prague, an exhibition probing the medical-cosmetic industry where cultural ideas of virginity are hacked and commodified through hymenoplasty and prosthetic hymens. We had a few questions for them.

-

Installation view of f-architecture, Cosmo Clinical Interiors, VI PER Gallery, Prague. Photography by Peter Fabo.

-

Installation view of f-architecture, Cosmo Clinical Interiors, VI PER Gallery, Prague. Photography by Peter Fabo.

How did you come across the idea of the artificial hymens in the first place?

Rosana Elkhatib: Well, in my graduate thesis I’d been looking a lot at bodies, but I was looking for objects to write about. Somehow I just typed “hymen” into Google and fell down a rabbit hole. I found them and I was like, “what?” Because I knew about hymenoplasty and the surgery, but I didn’t know that they actually sold artificial hymens on Alibaba.com. I can’t speak for all of us, but for me it was really interesting because it was a chance to take on this topic in a very different way. What does it mean? Who’s involved with this? And what are the ways it affects women?

Gabrielle Printz: So much spun out from the existence of that object. Here’s a thing you can hold in your hands as an object of sale, and that appends the body in a certain way, in relation to gendered and also cultural bodily expectations. It has all these components that we could approach. And then you have the space of the clinic, which we’re really interested in. It’s a project that is about negotiating between urgency and desire; as a woman in need of the procedure, you can access it or not access it, and that is a political question. But then there’s also the experience of doing it — how the clinic is outfitted, how the product is stylized in order to appeal to you to make you feel a certain way. So in Beirut, we actually visited a few clinics.

What are they like? What are the demographics represented in this kind of surgery?

Virginia Black: The spaces we are looking at are more for the upper-middle class.

GP: They’re definitely well-dressed women. We sat there in some of the lobbies. It was very uncomfortable because we were so conspicuous. It was hot and we were so sweaty. We ended up talking to a doctor there who was like, “What are you even doing here?” But all we wanted was to gain admission to the space, so it was a success. Beirut is interesting because it’s already a destination for medical tourism, so we visited clinics that were set up to accommodate both the need for the procedure, but also the indulgence, and a more luxury market. And the legality of it, it’s pretty open but the advertising is tricky. It has to be sort of evasive in some cases; in other cases it’s like, “this is a thing we do and we have a suite for vaginal or intimate services.” It appeals to both the desire for the procedure, but also the provision of what is still taboo there.

-

Installation view of f-architecture, Cosmo Clinical Interiors, VI PER Gallery, Prague. Photography by Peter Fabo.

-

Installation view of f-architecture, Cosmo Clinical Interiors, VI PER Gallery, Prague. Photography by Peter Fabo.

Can you tell me about your recent exhibition at VI PER Gallery in Prague?

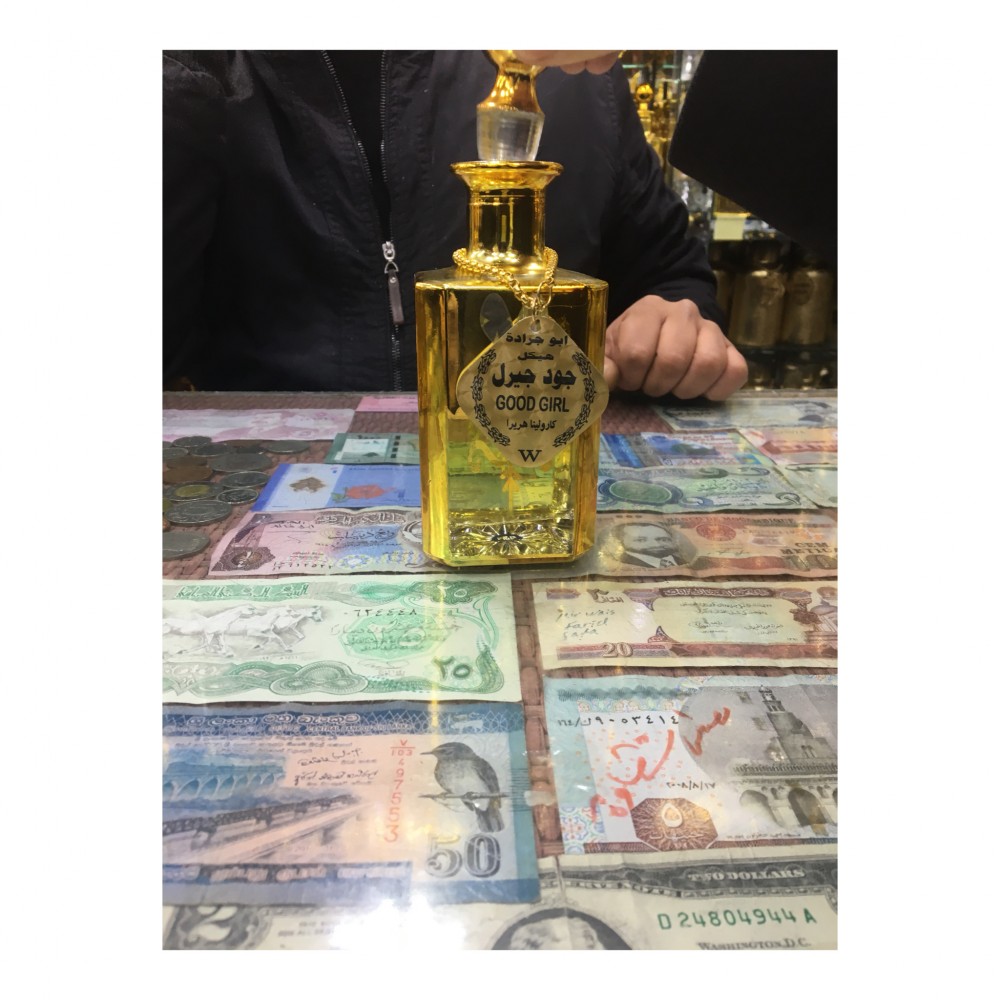

GP: The physical exhibition included our own “critical hymen objects.” There was a perfume, a chair, a rug, a wearable hymen, and they were situated in a way that it kind of feels like a clinic, like the ones that we visited in Beirut. There was also a VR experience that takes you through the literal spaces, filtered through a kind of fantasy of that navigation. It’s all these things that look at the evidence and performance of making or taking virginity, and then the scrutiny over the body. The chair is something from an 80s feminist health center pamphlet for what they called “menstrual extraction” — basically to perform an abortion at home. It has these beautiful illustrations of women coming together over a soft surface, like a pile of cushions, but then there’s a hand mirror, and the speculum device — objects that domesticize the clinic but turned inward in a way so that you can see yourself or be at work on your own body. So in the exhibition, you'd be sitting in our chair, in this cushion-y place to wear the VR headset. The mirror comes up sort of like a pad in its profile, but it’s curved up so you could see yourself and under yourself. We see it as performing the hymen in a way, from a extrapolated viewpoint. There’s also perfume and oils we got when we were in Jordan. We walked into a perfume shop and asked the guy...

RE: “What’s the scent of a young bride on her wedding night?”

GP: And he had it. Immediately.

VB: White musk.

GP: We smelled a bunch of them and some of them were absolutely putrid.

"Good Girl" perfume, designed for a young bride on her wedding night. Sourced in Amman, Jordan. Courtesy of f-architecture.

I’m interested in this idea of agency. A lot of the people deciding the regulations, or under what circumstances you can construct a hymen, are not the women using them?

RE: Right. It reminds me also of our responsibility to consider how we approach these topics and how we represent them. There’s also this idea when I was in Germany, of us being activists, and intending to emancipate women. It’s interesting for me to see how our work comes off sometimes as critical but sometimes as activist.

GP: I think we like the space between. But I think also, for the Hymen Project, a very easy thing to do would be to, say, go full bra-burning on the hymen. Like: “We need to deconstruct the artificial hymen so it cannot exist.” But of course it’s serving a very real need in some cases, and do we “liberate” these women from the terror of the artificial hymen, or do we dig into the product in a way that we can all understand? I think negotiating the relationship where there’s an exchange is important to us. You can have the critical project that extends these things, and then they become sort of storybook characters in that, and not your co-worker or colleague. But there’s the sense that you have a critical project about them or you’re helping them.

Why not both?

VB: We’ve spent so much time delicately trying to put this project together, and I think that it’s been very important for us to interview women about their experiences. Quality research takes a very long time, and building relationships with communities also takes a very long time.

RE: We’re collaborating with a podcast in Jordan to get interviews, but also some of the narratives are scripts and will be read by different voices. Part of it is because not all women want to narrate their stories, and part of it is also language, and finding different ways to have a soundscape that is accessible to the audience but still maintain some of the original voices and have them resonate.

VB: There’s also this concept of translation, because we’re trying to have components in English and in Arabic, but we think of the VR scenes as a kind of translation of atmosphere as well as of language, where the effect of these clinics and the attitudes of the people in them, and the kinds of barriers you have to go through in order to get there are communicated.

RE: In Jordan, you never find details. It’s like, you just have to know someone. But then in Egypt, clinics offer both options, either the procedure, or if you want you can just buy the cheaper artificial hymen.

Installation view of f-architecture, Cosmo Clinical Interiors, VI PER Gallery, Prague. Photography by Peter Fabo.

Does the clinic help you putting the hymen in?

RE: No, you have to put it in the night of the wedding, maybe an hour before.

I wonder if there’s like, a high season, since they're connected to weddings.

GB: “High hymen season.” That’s our next essay!

Text by Annette Lin. Exhibition photography by Peter Fabo and portraits by Casey Carter.

The second act of Still I Rise: Feminisms, Gender, Resistance, designed in collaboration with Nottingham Contemporary, is on view at De La Warr Pavilion through Monday, May 18, 2019.

Read f-architecture’s latest piece in issue no. 46 of Harvard Design Magazine.