INTERVIEW: Architect Tei Carpenter On Philosophy, The Future, And Her Public Hydrant

Meet Tei Carpenter, the founder of Agency—Agency, a Brooklyn-based architecture and design studio. Her practice ranges from exhibition design and inventive public-infrastructure projects (such as prototypes for public fire hydrants that double as drinking fountains) to buildings like the recently completed Greater Houston branch of non-profit Big Brothers Big Sisters. In conversation with curator Vere van Gool, the emerging architect speculates on philosophy and design, and the future of architecture as an industry and profession.

Exterior view of Agency— Agency’s design for the regional HQ of non-profit Big Brothers Big Sisters (2014–18) in Houston, Texas.

You named your architecture office Agency—Agency. What role does agency play in your work?

There’s a duality to the word agency — it can point to the practice of architecture as one with an ideological and aesthetic agenda while at the same time make space for the types of work we do and want to do at multiple scales and with different people, organizations, and cities. In the name Agency—Agency those meanings are doubled and connected with a line. In a sense I’m trying to set up a platform for how to approach projects now and in the future, and the repetition of the word is a stubborn reminder of that.

Architecture is purely about a “man-made” world, and as such a major contributor to many of the environmental problems we’re facing today. What are your thoughts on something like a Hippocratic Oath for architects?

It’s tricky to correspond the body and the building because the Hippocratic Oath is so embedded in the medical world. The idea of healing or improvement by a doctor is fundamentally objective, but “healing” or “improvement” is much more subjective for architects. Who decides whether an architectural act is actually making a positive contribution and for whom that contribution is intended? It’s much more debatable.

Material samples at Tei Carpenter’s studio photographed by Sangwoo Suh for PIN–UP.

We perhaps see how architecture shapes futures most urgently when it comes to climate change. How do you see the design profession working to tackle the climate crisis?

There’s a quote in Jason W. Moore’s book Capitalism in the Web of Life (Verso, 2015) along the lines of, “We can’t solve the problems of today with the tools that created those problems.” We need new tools and new approaches. It’s about making behavioral changes, not about the application of technologies. More and more, I think we should also go back and learn from more elemental and primal means and ways of working, studying the aesthetic and thermal properties of materials like rocks, earth, and even the potential of things like tidal and lunar-gravity power.

Going back to the past to explore the future. Has this concept manifested in any of your recent projects?

For the 2019 Oslo Architecture Triennale, I collaborated with a great group on the Intentional Estates Agency, an interactive public installation and publication that’s now at (New York City arts space) Printed Matter. The project guides its participants to models of experimental living outside of a limitless-capital-growth paradigm. We assembled a catalogue of historical and contemporary intentional communities and social experiments from around the world, from the Hancock Shaker Village, founded in 1790 here in the U.S., to the phalanstery, as theorized by Charles Fourier in 19th-century France, to the Human Power Plant project that started up a couple of years ago in the Netherlands. For us, as a group of architects and artists, it was a way to better understand the motives and forms of these models of society and their value systems as a first step towards proposing alternatives.

Tei Carpenter photographed by Sangwoo Suh for PIN–UP.

You have a background in philosophy, which is a tool to reflect and unravel. Some might say that’s almost the opposite of architecture, which is focused on building very real things. What motivated this change from deconstruction to literal construction?

I grew up around architecture (Carpenter’s mother is architect Toshiko Mori), so when I was younger I tried to avoid it. I worked in documentary film, with a small production company which made a film about Shirley Chisholm (the first black woman elected to congress). I spent time in the art world, working with the artist Ann Hamilton on a book about her object-based work. But I eventually came back to architecture. To me, architecture offers a wide enough umbrella to merge a number of my interests in philosophy — especially logic — with art, story-telling, social engagement, and collaboration.

What are some of the biggest risks you’ve taken since launching your office a few years ago?

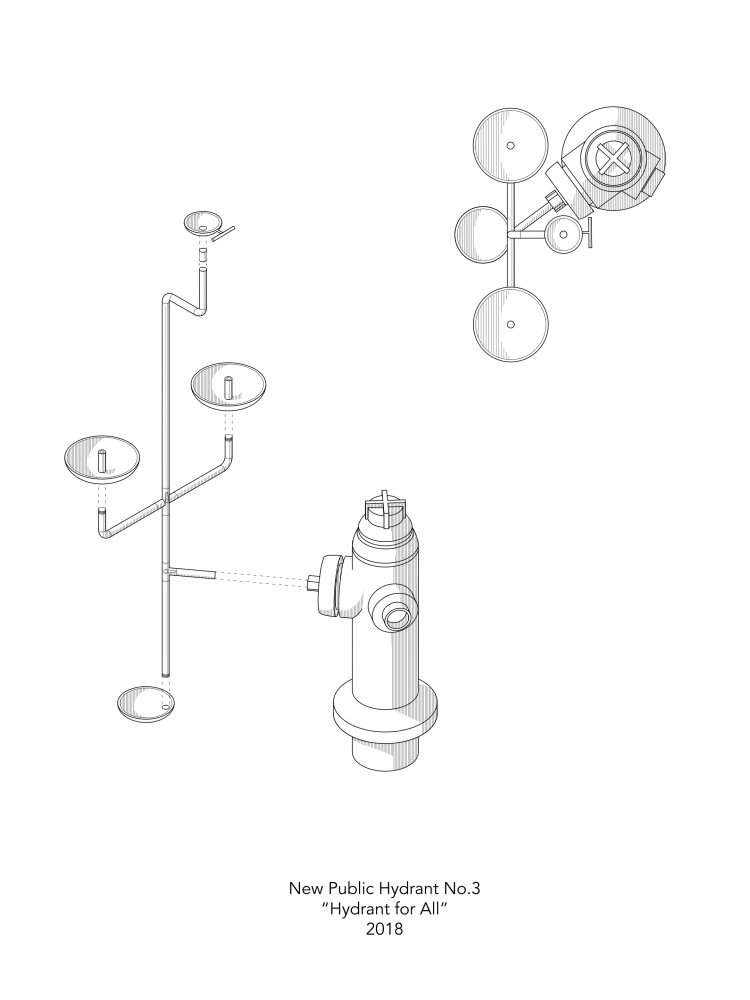

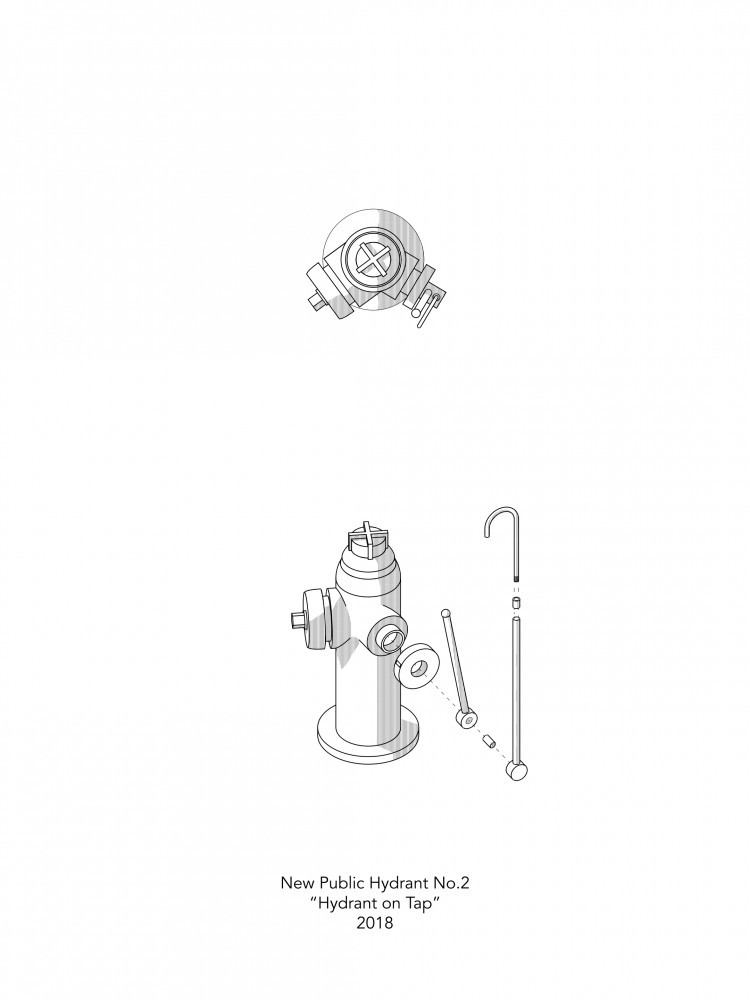

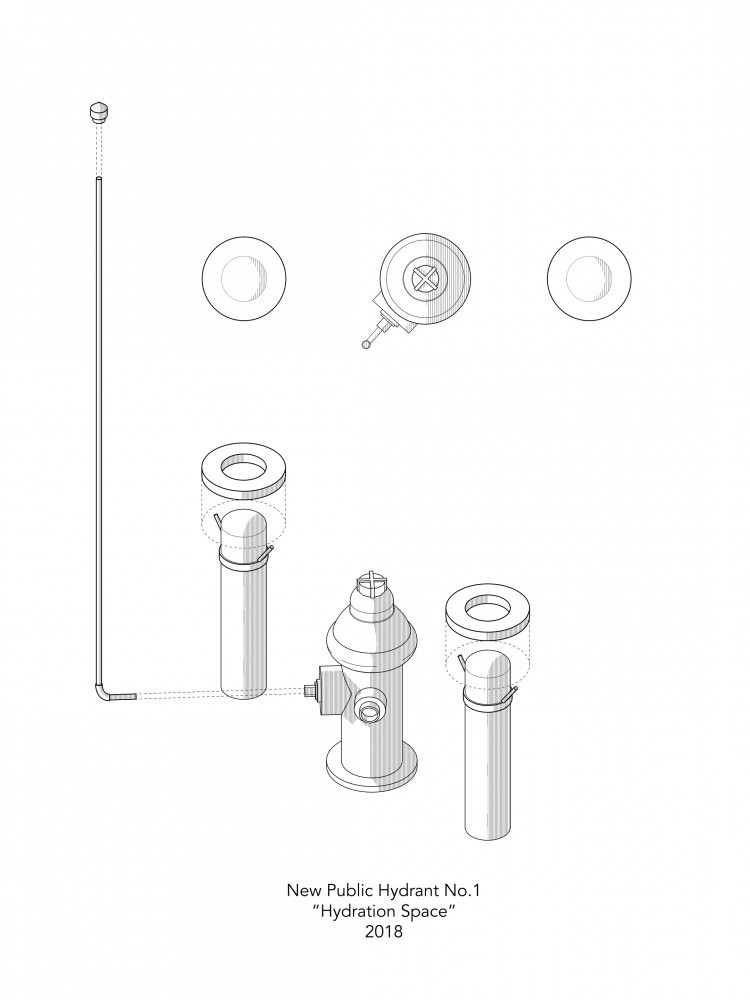

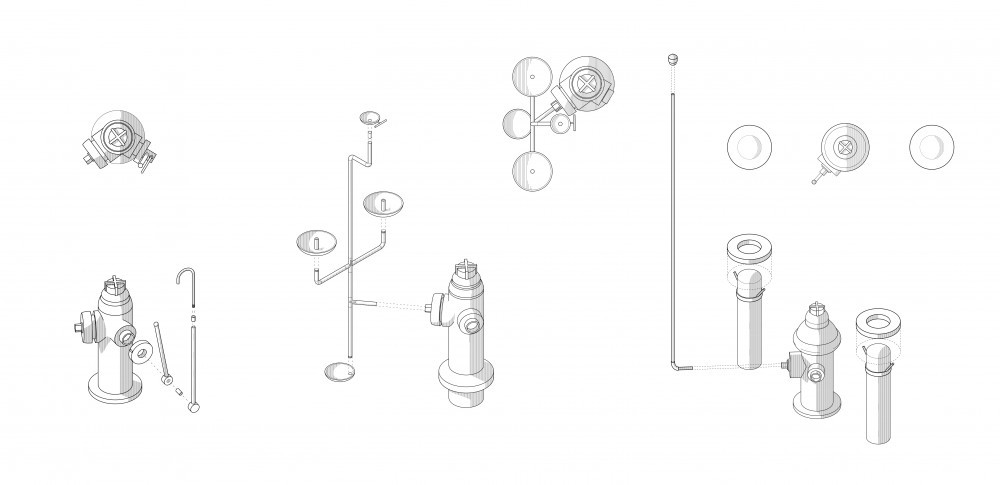

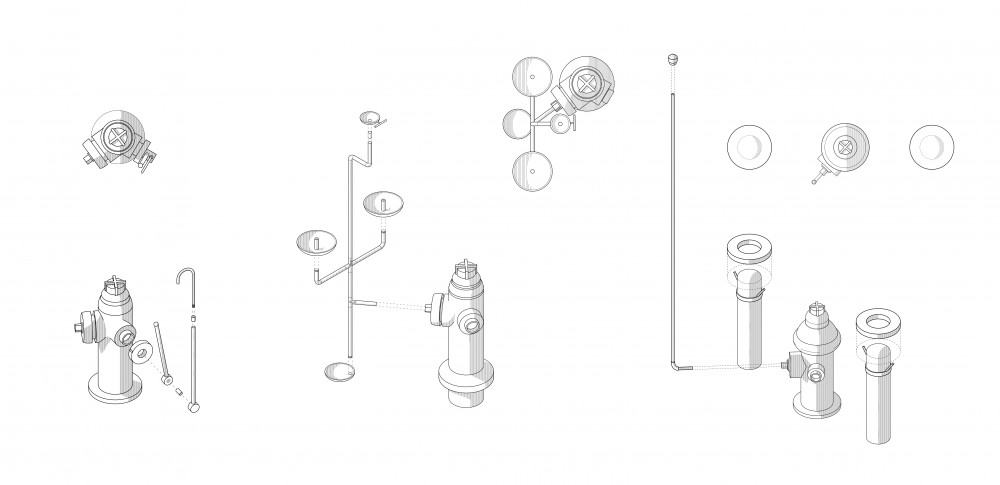

Technical drawings for New Public Hydrant, a collaboration between Tei Carpenter and Chris Woebken that turns fire hydrants into drinking fountains.

What would be your ideal vision for architects in the future?

I hope that soon there might be another version of the WPA (Works Progress Administration, an ambitious employment and infrastructure program created by President Roosevelt in 1935), something akin to the Green New Deal, that creates jobs and also provides opportunities to design public spaces, public works, and infrastructure. I would like to experiment with designing for bigness and also work in incredible wild environments, like designing charismatic water infrastructures in remote snowy mountain ranges, or new energy landscapes in the desert.

This interview is for PIN–UP’s Sun Issue. What are your thoughts on the sun?

The first thing that comes to mind is Philip Glass’s opera Akhnaten, which I saw a few months ago. It was fully intoxicating. The scene when Aten the sun god ascends a stairway framed by a massive glowing sun orb is still burned in my mind. It was perceptually mystical, visceral, and I read that it was designed to feel like a weird fever dream.

Text by Vere van Gool.

Portrait by Sangwoo Suh. Work images courtesy Agency—Agency.

Taken from PIN–UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.