LOW LIFE: Revisiting Robert Moses’s Exclusionary Design Scheme At Jones Beach

The design of Jones Beach State Park was helmed by New York “master builder” Robert Moses. The project, completed in 1929, appropriated funds from the New York State Legislature to build what set out to be, essentially, a “whites only” public beach.

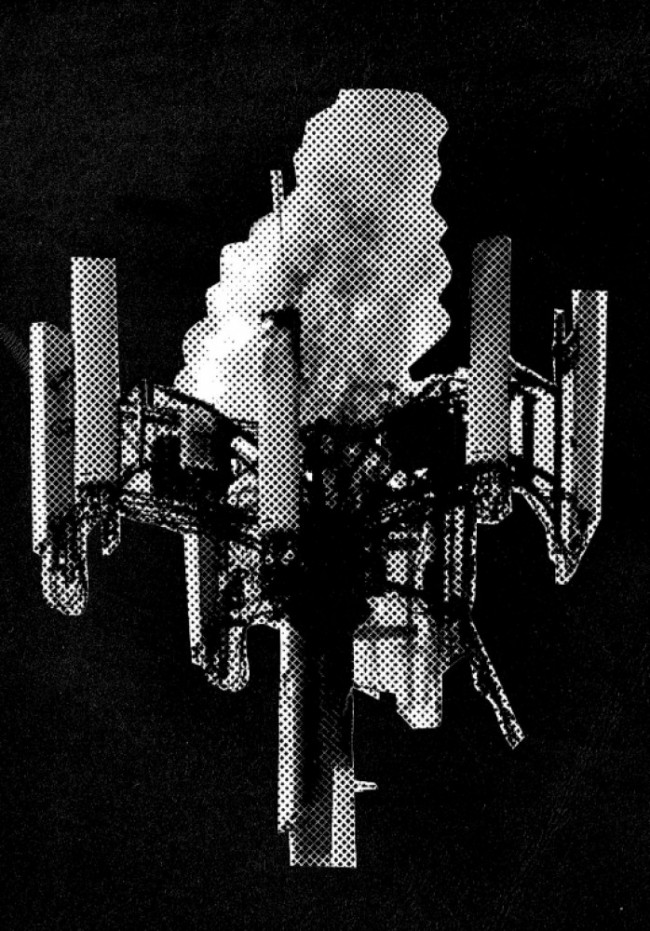

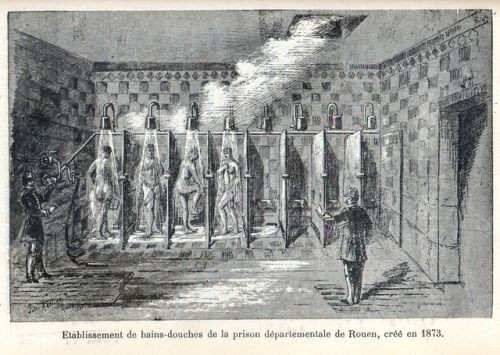

Moses harnessed the power of design to keep Jones Beach segregated. Using his position as the Chairman of the Long Island State Park Commission, he demanded that bridges along the parkways that led to Jones Beach be built unusually low. A municipal bus is typically nine feet, eleven inches, but many of the parkways’ bridges are just nine feet tall — a few are under. These low bridges were not an oversight, but rather a concrete example of Moses’s racist agenda. The bridges barred public buses from accessing the beachfronts, making Jones Beach only reachable by car — an ownership demographic that unsurprisingly skewed largely white middle- and upper-class. Moses’s parkways were touted as a celebration of the booming automotive age; the necessity of a car was seen as a symbol of American exceptionalism rather than a tool for its segregationist agenda.

-

Intentionally low bridges on the way to Jones Beach designed in 1929, part of a racist agenda to exclude beachfront access to certain demographics. Photography by Chris Mottalini.

-

Low bridges on the Southern State Parkway restricting bus access to Jones Beach built under the direction of Robert Moses. Photography by Chris Mottalini.

“The question of access has to be thought about both as the journey to, and the experience at, a place,” says Kelsey Edelen, a Philadelphia-based urban space strategist. “Only looking at one part of this equation can often obscure its true lack of inclusion.” The exclusionary infrastructural model of access to Jones Beach is a stark relative to the “Whites Only” signage of the Jim Crow South; it represents, in the form of its own set of signals, a more insidious and more permanent racism. The Long Island bridges design is of course merely one example of how architecture has upheld, and continues to uphold, the segregation of public spaces — specifically spaces of leisure.

-

Jones Beach State Park parking lot photographed by Emily R. Pellerin.

-

Jones Beach parking lot photographed by Chris Mottalini.

New York-based architect, writer and researcher Alicia Olushola Ajayi argues that “there is an implicit bias in the use of ‘public space’” because there are so few examples of it “that are conceptualized with meeting the needs of the general public.” She goes on to question the meaning of “general public” in the first place. “Perhaps more accurately, (is it) the prioritized public? Or do we just mean ‘whiteness?’ Maybe we need to come clean, that when we say ‘public space’ in the urban environment it is really intended and designed for a select few.”

The case study of Jones Beach supports Ajayi’s assertion: public spaces are built for specific populations to engage with specific types of recreation. It also reveals the American shibboleth that leisure is for white people.

Ocean waves at Jones Beach State Park in Long Island. Photography by Chris Mottalini.

In her 2016 TED Talk, cultural theorist Dr. Brittney Cooper breaks down how time (like race, and like the fallacy of truly public space) is in essence a white construct. She argues that "the racial struggles we are experiencing are clashes over time and space.” When we apply this theory to the concept of leisure, we see, then, that white people retain the power to say when and where and for how long people of color can recreate, relax, or simply rest. The constructed segregation of spaces of leisure perpetuates this. “I think about this a lot,” reflects Ajayi, “and how (NYC’s) Open Streets has unfolded as these magical street festival atmospheres in whiter and richer neighborhoods in the space of quarantine life, which have been supported by the City. It reinforces that leisure is a white thing.”

-

Leisure infrastructure on the boardwalk at Jones Beach State Park. Photography by Corey Kingston.

-

Built-in table and seating at Jones Beach State Park. Photography by Corey Kingston.

In spaces like Jones Beach, or New York City’s streets-during-pandemic, the psychological impact of one person’s designed experience of leisure is fostered and upheld to the neglect (if not expense) of another’s. Edelen cites how tangible design decisions affect “the mental and psychic effort of experience,” requiring “designers and planners to focus on the holistic process of using a space.” The necessary concern is beyond physical engagement — it’s emotional, embodied, lived and human. Critically engaging with the provenance of our public spaces and spaces of leisure — in this case the ones infrastructurally and architecturally prescribed to us — arms us, as designers, with a more informed jumping off point and greater liability for our own contributions to the built environment to be anti-racist, ably inclusive, and anti-segregationist.

-

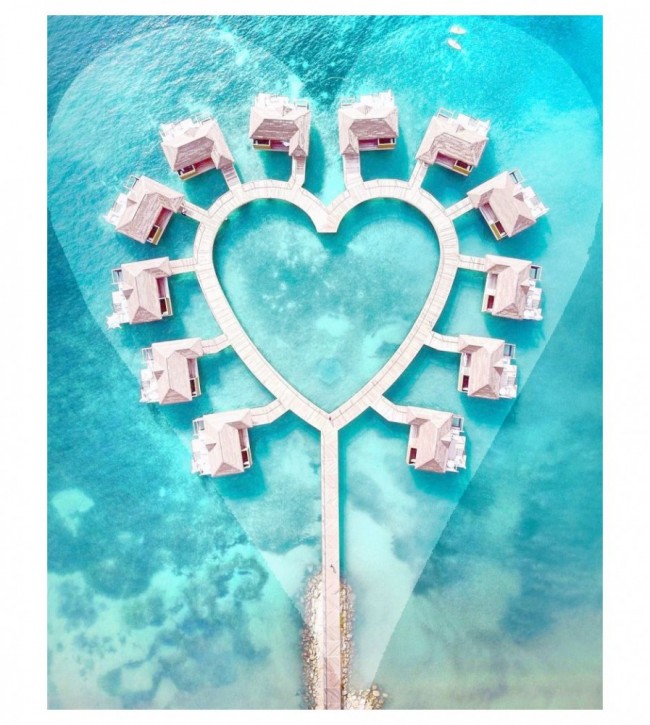

Permanent modifications built into the asphalt for the game corn hole at Jones Beach. Photography by Corey Kingston.

-

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo invested $100 million dollars into the revitalization of Jones Beach State Park in 2016. Photography by Corey Kingston.

Our research prepared us for the exclusionary infrastructure of the parkway, but during a recent visit to the state park, what struck us was the overt racial politics of the park’s leisure activities. We were immediately met with the excessiveness of “leisure” as a program. Boardwalk signage boasted that, in 2016, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo invested $100 million dollars into the revitalization of the State Park, concretizing it as a monument to leisure rooted in white pastimes: we witnessed a new and sprawling zip line course (the commodification of which has been led by Western tourists), permanent modifications built into the asphalt for the game corn hole, and expansive shuffleboard courts (not to mention the Dave Matthews Band-funded fountain park). We quite easily “followed the money” along the boardwalk, making note of how these fiscally prioritized spaces were promoting leisure, of what kind, and for which implied users.

Our internal goal, and our outward prompt, is for each of us to create from the space of challenged perceptions. American architecture has built and upheld pillars of racism in every corner of this country. As we look to removing statues of white supremacists, we must also harness the power of design to attend to the faceless monuments of infrastructure. Though banal, they are hardly benign.

Text by Liza Curtiss, Corey Kingston, and Emily R. Pellerin.

Le Whit is a multi-disciplinary design studio run by principals Liza Curtiss and Corey Kingston. Emily R. Pellerin is a writer and communications strategist.

Photography courtesy Le Whit.

Special thanks to contributors Kelsey Edelen and Alicia Olushola Ajayi.

An earlier version of this essay was originally published on LeWhit.com.