INTERVIEW: Curatorial Visionary Paola Antonelli On Design As Politics And The New Material Revolution

Italian-born Paola Antonelli has been the Senior Curator of Museum of Modern Art’s Department of Architecture and Design since 1995. During this tenure the author, editor, and trained architect has advocated for an expanded sense of technology’s role in design, stirred controversy by showing video games in MoMA’s hallowed halls, and explored the relationship between design and human violence. One of her enduring fascinations is new materials, an obsession that’s shaped her curatorial practice from her very first MoMA show Mutant Materials in Contemporary Design (1995) to more recent exhibitions like Broken Nature which is now on view at MoMA until Summer 2021 (it debuted in 2019 at the Triennale di Milano). Another is Antonelli’s longstanding interest in the design and politics of safety, which has proven itself especially prescient this year in our pandemic era. Antonelli sat down with Tiffany Lambert to talk about curating in this transformative moment.

-

Aki Inomata, Think Evolution #1: Kiku-ichi (Ammonite) (2016-17) part of Broken Nature (2020). Image courtesy the artist and Maho Kubota Gallery.

-

Kelly Jazvac, Plastiglomerates (2013) part of Broken Nature (2020). Image courtesy Kelly Jazvac.

-

Neri Oxman and The Mediated Matter Group, Totems (2018) part of Neri Oxman: Material Ecology (2020). Image courtesy Neri Oxman and The Mediated Matter Group.

Tiffany Lambert: Let’s start by talking about the role of museums in the current moment. With widespread dismantling of structures, social systems, and public arts funding, what changes to the institutional framework do you envision or hope to see MoMA tackle?

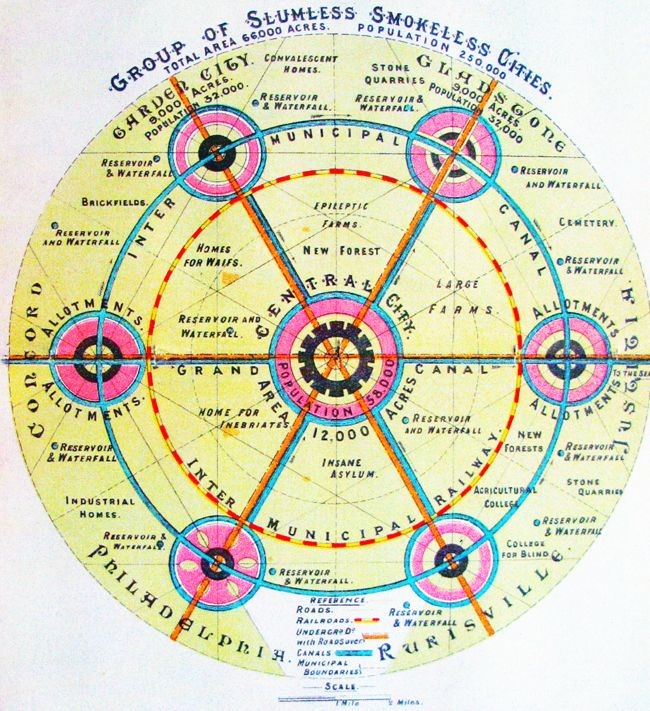

Paola Antonelli: I see the work ahead of us, believe it or not, as exciting. There’s so much to do. Museums can be agents of change and this is a transformative moment for the world, so this is an enormously important time for us. Of course, we need to begin with changing ourselves, evolving beyond our past limitations. I’m proud of many museums, MoMA in particular for how we have begun the process. About ten years ago several initiatives happened at MoMA. We recognized our shortcomings in different areas. Even though I do not remember talks about decolonizing the arts at that time, there were a few first attempts in that direction — the acknowledgment that our point of view was not absolute, that there are indeed many “canons.” We realized that we needed to study in much more depth the African continent, Eastern Europe, Southeast Asia, and Latin America. We started the C-MAP (Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives) initiative in 2009, and the Modern Women’s Fund in 2010. We brought in scholars, organized trips for MoMA curators, attended symposia and went on studio visits all over the world, and really researched in-depth all of these different aspects of Modern that were not represented enough by MoMA, yet. The first part of this ongoing research is what you saw at the reopening of the museum in the fall of 2019. I was very proud and, almost universally, the rehanging of the collection was praised for its attempt to change the perspective from Eurocentric, white patriarchy, Bauhausian — in other words, all yesteryear — to more contemporary, inclusive, diverse, critical, and questioning. We still have a lot to do when it comes to changing the DNA of the institution but I am proud of what we’ve done so far.

Art is necessary to life, and in New York, it’s especially necessary because it provides all of these lateral expansions of time and space that you might not feel otherwise because the city is so compressed. I feel that New Yorkers are able to survive and thrive because they have all these pockets of culture, this contact with other people’s creativity that really expands our life and our soul every day. I do not only mean the culture that you find in museums and theaters, but very simply the desire to share different point of views, everywhere. In the past months, people have been really traumatized, it’s been a tough and tragic time, and cultural institutions were closed during the hardest moments. Understandably, but we could have helped. And in general, cultural institutions, curators, writers — we have not yet found a way to make the world fully understand the importance of arts and culture in the progress and wellbeing of a society. I believe museums are places where you can go ponder the difficult matters of life, where you can think of death, injustice, sickness, aging, racism. Where you can think of how to protest, mourn, empathize, learn how to change. I feel that not only MoMA but many museums are trying to be of service to people in their everyday lives, showing that museums and art are tools for living.

Kazuo Kawasaki, Carna Folding Wheelchair (1989) part of Mutant Materials in Contemporary Design (1995). Image courtesy MoMA.

For a long time you’ve been a part of the conversation on how museums can relate to the digital space. I’m thinking of examples like Design and Violence, when you found this alternative curatorial format for it online. I believe you also did the first website at MoMA.

Yeah, I did. I even coded it myself (laughs). The online has always been a parallel dimension, but the way it has been supporting museums has changed. The first MoMA website was connected to my first exhibition there, Mutant Materials in Contemporary Design (1995). Because a book has to be closed several months in advance, I wanted to make sure there would be a record of the final checklist, accessible to all. That was the intent. At that time, it was archival documentation. It’s still there, and just last year somebody told me, “I’m so glad the checklist is still available.” After that, a few other curators tested the grounds. Barbara London was the first to have a blog, using it as a diary of her trips to China and Japan to look at video art. So, it went from archive to documentation and blog. Then, there was the period of the Flash-based — unfortunately — websites. The one that I still consider the most beautiful is Design and the Elastic Mind (2008). At that time, these websites were projects of their own. I used to think that every exhibition happened in three spaces and three different versions–– the gallery, the catalog, and the website.

Neri Oxman’s Aguahoja (2014–20) is a collection of biopolymer composites, 3D-printed from natural artifacts like bones, tree branches, and insect exoskeletons. Image courtesy Neri Oxman.

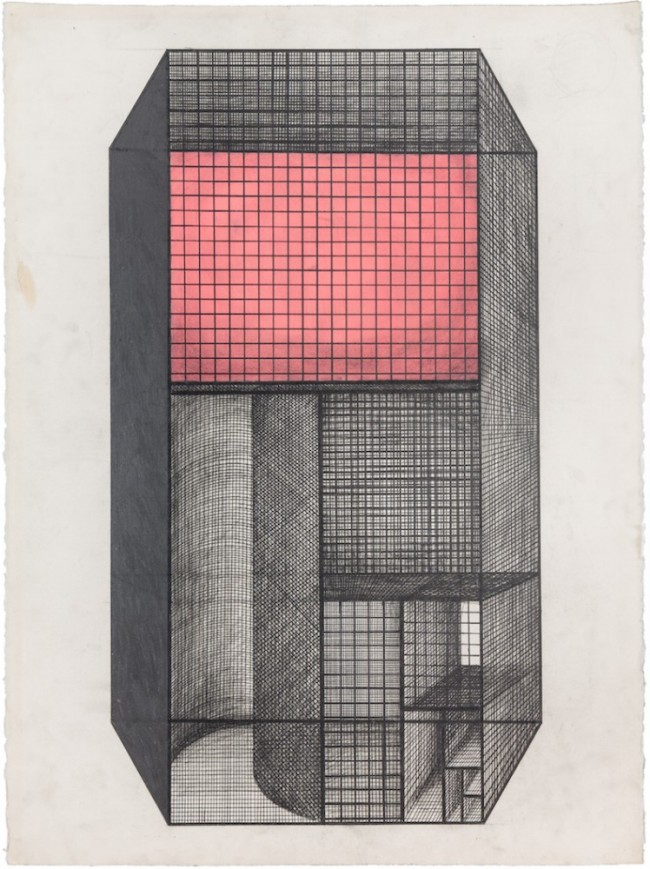

I wanted to touch on your recent Neri Oxman exhibition Material Ecology and investigating revolutionary materials, something that’s been a focus of yours since at least Mutant Materials.

Neri and I met in 2007, when I was researching Design and the Elastic Mind, and we realized we were kindred spirits because we believed that advanced technology — 3D-printing, computational design, etc. — should never be an end, but rather, the means to get to a higher goal, which was that of understanding and embracing nature, even working with nature. I saw in her the same desire to get to a new type of organic design that is not about imitating the forms of nature, but really “doing it” as well as nature does it. Neri was already doing that in 2007 by trying to distill algorithms out of certain natural behaviors — barks of trees or scorpions’ paws, for instance — and then translating them for different purposes. With the first Silk Pavilion in 2013, she went one step further. Instead of trying to capture the behaviors of nature, she decided to co-opt them and work with nature. She “contracted” thousands of silkworms as builders. The Silk Pavilion to me was a wonderful epiphany. How can you work with nature while also improving the conditions of your construction workers — the silkworms? Usually in the silk industry, they are boiled in the cocoon so as to be able to extract the silk. It’s brutal. Instead, in the case of the Silk Pavilion, they die on their own, after finishing their work and their life. The years went by, the research widened, and Neri started working also with bacteria and with melanin, among others. You could see her experiments in Material Ecology, the exhibition that just closed at MoMA (you can still catch it online). As far as silkworms are concerned, her research evolved so as to make them even more responsible for the final result. So, in a way, she is working toward interspecies design.

Paola Antonelli photographed by Saheer Umar for PIN–UP.

What are the most compelling ways of making with new materials today?

I would say that the superstars of biodesign right now are still algae, silkworms, bees, and mushrooms. And some bacteria, E. coli especially. It’s hard to even begin to describe this field, it is in a moment just after the initial frenzy. It’s not very old. The first Biofabricate (a conference devoted to applications of biomaterials) was only, I think, six or seven years ago. But at that time, wide-eyed biologists were working with mouth-agape designers and dreaming up startups. Now we’re in the moment in which some startups are closing — the natural selection of the species is happening already — and some are consolidating. It’s incredibly fascinating. Neri is starting her own company, with a viable business, which is very good because experiments can be fabulous, but unless you’re able to translate them to reality, they remain only ideas.

I don’t think you would disagree that design plays an important role in revolutions. I think that’s something you’re currently exploring with Design Emergency, the IG Live project you conceived with Alice Rawsthorn. Could you talk about some of the examples and strategies you’ve uncovered so far?

Of course. I would like to start by saying however that I don’t believe that design by itself makes revolutions. I think that revolutions happen because of teams working together, whether it’s scientists, technologists, politicians, or designers. Revolutions however would never come to life without design. Design is the enzyme that metabolizes revolutions to transform them into life. It’s fundamental. Without design, nothing happens. With Design Emergency, Alice and I pursue our mission of showing the incredibly multifaceted nature of design to the world. Alice started a series of posts about design in a pandemic on her famed Instagram feed at the beginning of the Covid-19 crisis, and we decided to complement it with a separate feed that would celebrate the human beings that are sometimes missing in the dissemination of design, by explaining their thinking and their process. We would like people to stop thinking that design is only cute chairs or expensive objects. We want people to live a more interesting, more empowered life. If all citizens start understanding design at a deep level, they can really push back. They can demand better. Especially now where (at least in the U.S.) we don’t really have any protection at the government level, knowledge is power. It’s not only about culture, intellect, and style — it is politics. We are conscious that this is an amazing opportunity to show the power of design to the world. And we also want to make sure that people start training themselves to recognize good design when they see it.

Installation view of SAFE: Design Takes On Risk (2005–06) including Raúl Cárdenas Osuna, Securitree transmitter, prototype.

This project Design Emergency reminded me of your show SAFE: Design Takes on Risk (2005–06), and how it evolved from an exhibition about emergency. Is there anything you took from that for this project?

Of course! The current situation reminds me also of another project called Workspheres in 2001, which also contemplated the idea of working from home, remote work. Same as today. The only difference is that, at the time, there was no video. But, there were the same frustrations — sometimes technology doesn’t work — and also the same worries — do you have to change your clothes as if you’re at work? Do you take a commute around the block? When it comes to SAFE, I was working on it in 2000, when it was called Emergency. It was about emergency rooms, ICUs, ambulances, fire trucks. It was an exhibition that would’ve opened in 2001 or the beginning of 2002, but then 9/11 happened. After a few months, I started thinking about it again. Only instead of thinking of it being about design as reactive, it changed to focusing on proactive and preventative design. SAFE, nonetheless, had a lot of the objects that we can think about today in the Covid era. It had respirators, it had shelters. It was an exhibition that really satisfied me because it put me in touch with worlds that I didn’t know, from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to manufacturers of medical equipment. The whole idea behind the show was for it to be non-denominational, covering safety in the Sahel Desert and the Upper East Side of Manhattan. It had Band-Aids for blisters and devices to extract water from the sand of the desert. It was about the kind of design that keeps people alive, safe, dignified, comforted and even comfortable.

Paola Antonelli photographed by Saheer Umar for PIN–UP.

A lot of the work you’ve done feels prescient and has gained renewed meaning today because you’ve managed to stay responsive to society’s shifts.

Thank you, but in a way, it was a no-brainer. It’s what people need and what design does, it’s timeless. We need safety. It’s the Maslow hierarchy of needs. And we need to work. When I have the opportunity to do exhibitions that are about life, they always seem timely.

Interview by Tiffany Lambert

Tiffany Lambert is a curator, educator, and writer based in New York. Her work has appeared in PIN–UP, Cultured, Domus, Finnish Architectural Review, Surface, TANK, and The New York Times, among others.

Portraits by Saheer Umar.

All other images courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.