BOOK CLUB: Race and Modern Architecture Confronts The Legacy Of White Supremacy

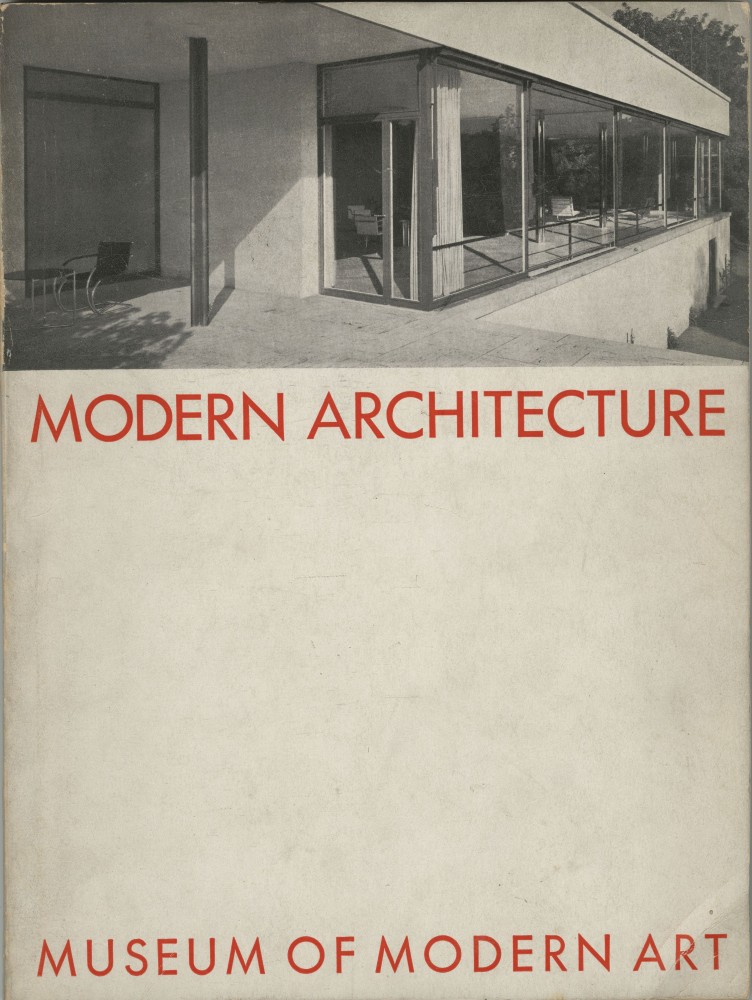

It was never a secret that Philip Johnson was a white supremacist — it’s just that until very recently, this widely known fact had never been meaningfully addressed. That all changed in December, ahead of Reconstructions, MoMA’s first exhibition of Blackness in architecture, when the Johnson Study Group, a collective of architects, artists, and educators (many of whom were part of the show) called for the venerated architect’s name to be removed from honorifics like public spaces and leadership titles. In an open letter to MoMA and the Harvard GSD, they provided ample evidence of Johnson’s unfitness as a namesake: During his tenure at the museum, he had translated and disseminated Nazi propaganda and “effectively segregated” the museum’s collections. “Under his leadership,” they wrote, “not a single work by any Black architect or designer was included.”

MoMA responded with a small and temporary gesture, covering Johnson’s name with a manifesto by the nonprofit Black Reconstruction Collective for the duration of Reconstructions. As most architectural media seemed to nod along with approval, Johnson fans still lit up comment sections to dismiss the letter as an attempt at erasure, another consequence of misguided cancel culture. “When the goal is inclusion, is a tit-for-tat banishment necessary or even useful?” architectural historian Michael Henry Adams opined in The Guardian, rushing to Johnson’s defense. “I’m invested in hoping Philip Johnson’s youthful outrages are forgivable.”

Whether or not we should forgive Johnson is beyond irrelevant today; not only is he dead, his tremendous legacy is at no risk of suddenly disappearing. (And to clarify, the Johnson Study Group had only asked for his removal from public space: “There are multiple private foundation sites preserving built work of Johnson,” they commented on Instagram. “Regarding those, we officially don’t give a fuck.” For me, what’s really up for discussion now is this long-standing let’s-just-get-over-it approach to racism. As a shield from accountability, it’s not only allowed the outdated ideals of known white supremacists to flourish in the canon, it’s also left architecture woefully unprepared to contend with racism in the present day.

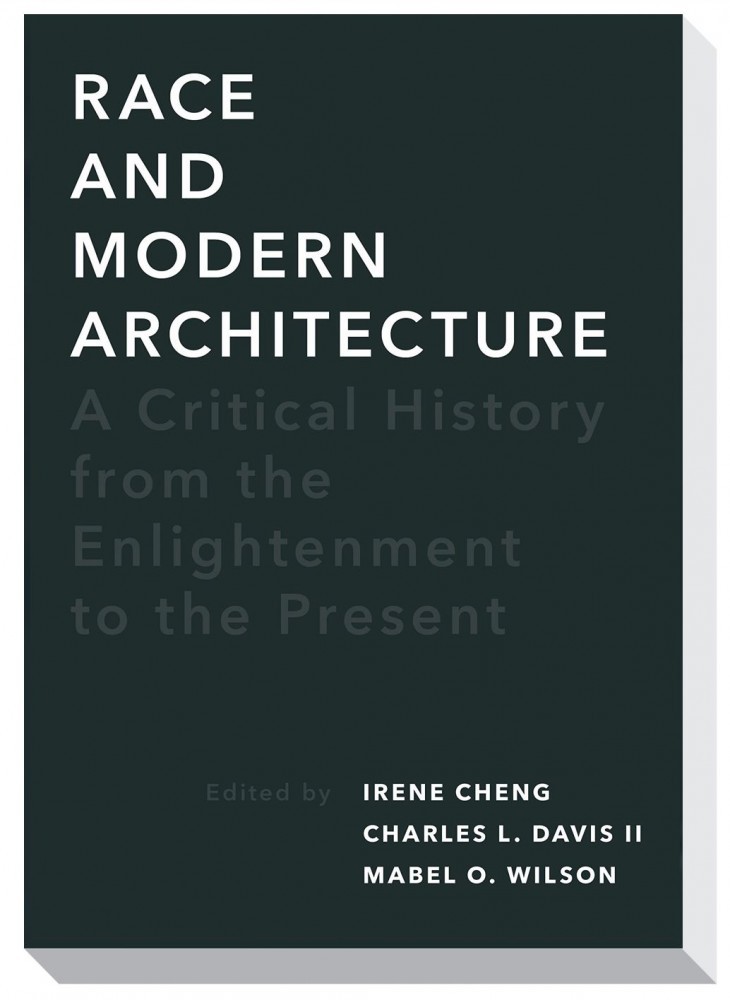

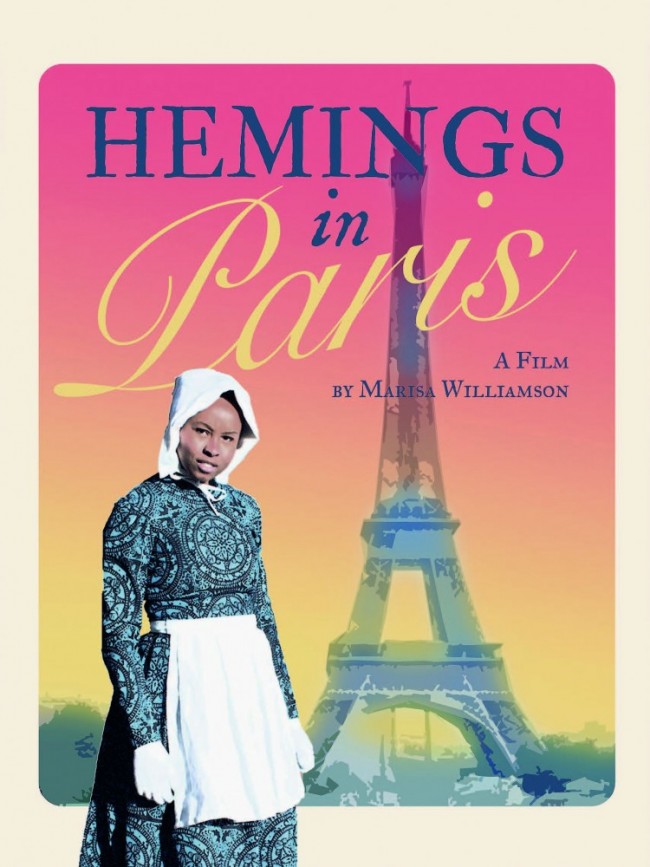

Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present, edited By Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis II, Mabel O. Wilson (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020).

The new book Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present confronts head on that “architectural historians have traditionally avoided the topic of race.” This timely collection of academic essays, co-edited by Mabel O. Wilson (co-curator of Reconstructions), Irene Cheng, and Charles L. Davis II, does the vital work of rehashing holes in architecture’s historical record, where instances of imperialism and white supremacy have been brushed off as inconsequential, “outside the proper boundaries of the discipline.” Each of the book’s contributors examines where these intentional blind spots have left their indelible marks on the way architecture is taught and defined, and how its consequences continue to shape the built environment. Over the course of 18 case studies, what becomes clear is that Johnson is only a small part of the story.

The first chapters rewind all the way back to the Enlightenment, the era where our modern ideas of race began to emerge. The idea of race as “a concept of human difference,” the book contends, coincided with the formation of human hierarchies. As Enlightenment philosophers wrote of universal liberty and human rights, they also accepted the exploitation of darker-skinned people as a consequence of an imagined intellectual and aesthetic inferiority — a mode of mental gymnastics that could reconcile the contradictory inhumanity of slaveholding.

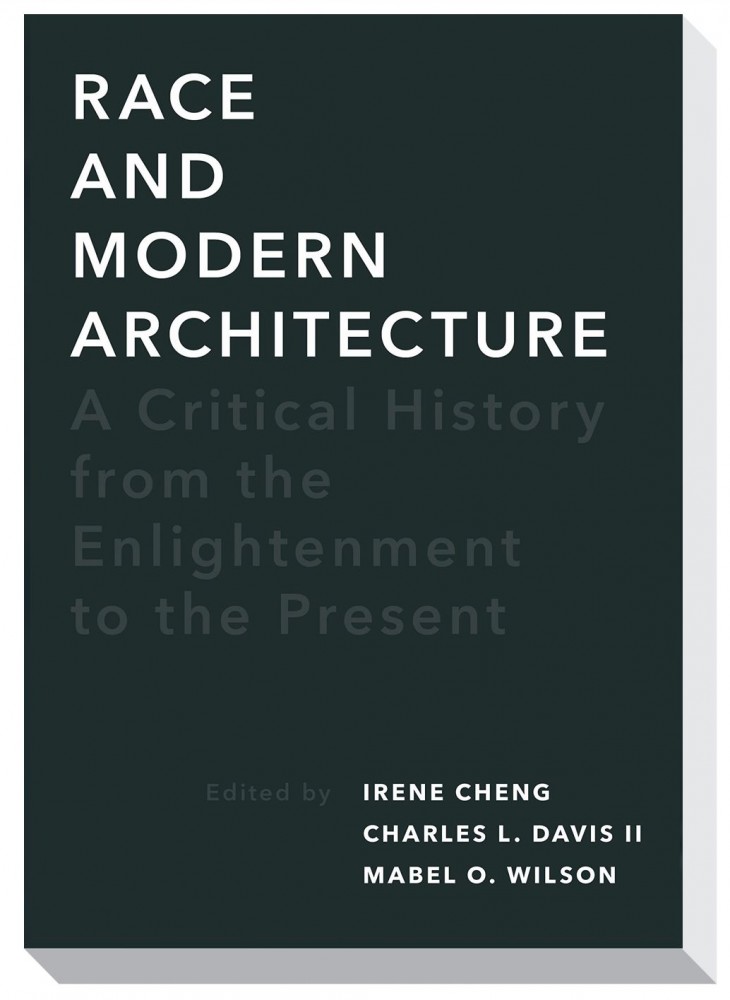

An 1805–07 portrait by Gilbert Stuart of U.S. president Thomas Jefferson, who was both a prominent slaveholder and a proponent of Neoclassical architecture, referencing ancient Greek and Roman building styles that to him symbolized ideals of democracy and civilization.

“Africans,” Immanuel Kant wrote in 1764, had “by nature no feeling that rises above the trifling,” nor had they produced “anything great in art or science or any other praiseworthy quality.” Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), third U.S. president, self-taught architect, and prominent slaveholder, wholeheartedly agreed. Seeking to establish an American architecture in the late 18th century, Jefferson’s Eurocentrism steered him towards European precedents in his design for the Virginia Capitol Building. Wilson’s first chapter, “Notes on the Virginia Capitol,” describes how the pediments and white columns that he borrowed from Greco-Roman antiquity were meant to telegraph values of democracy, taste, and civilization to the rest of the world. In “Drawing the Color Line,” Reinhold Martin describes how Jefferson designed mechanisms of silencing and erasure to keep the more sinister aspects of America’s founding from view. Enslaved people serviced these buildings from underground dumbwaiters, through back staircases, and from behind revolving walls, out of sight and out of mind.

That, according to the early chapters of Race and Modern Architecture, is how Neoclassicism became the default in American civic architecture. When President Donald Trump mandated that all federal buildings be constructed in the Neoclassical style in 2020, it suddenly became easy to recognize its Eurocentrism as rooted in white supremacy; architectural media eagerly pointed out its similar appeal to Adolf Hitler, yet another obvious external villain. Introspection, however, remains a more difficult task. By starting with Neoclassicism, Race and Modern Architecture lays down the proper groundwork for reassessing the canon in the same terms as Jefferson’s architecture: as a monument to whiteness, where the more uncomfortable details are hidden beneath the floorboards.

The book covers case studies from around the globe, but a particular narrative forms along the trajectory of the American experiment, where policy, media, developers, and planners enforce whiteness as a condition to owning any piece of the built environment. White supremacist notions traveled westward with Manifest Destiny, Charles L. Davis II writes, where architecture was a tool of settler colonialism, “promoting an exclusively white definition of American character.” Dianne Harris explains how glossy shelter magazines sold the suburbs as an exclusively white fantasy, promoting 20th-century practices of redlining. And Andrew Herscher examines how in the present day, developers weaponize the word “blight” against low-income communities of color, a justification for destroying them in favor of more profitable real estate.

Together with French architect Charles-Louis Clérisseau, Thomas Jefferson designed the Virginia State Capitol in Richmond, completed in 1788, modeling it after the Maison Carrée, a Roman temple in modern-day France.

As 2020 saw a landmark number of firms and institutions make pledges to anti-racism, an essential takeaway from Race and Modern Architecture is that racism is not always glaringly obvious; in fact it’s the most subtle versions that survive unacknowledged and unchallenged over the years, simply flying lower and lower under the radar of progressive cultural shifts. Irene Cheng’s chapter, “Structural Racialism in Modern Architectural Theory,” puts Johnson’s seemingly neutral precepts of 20th-century Modernism in direct lineage with 19th-century ethnographies, where ideas of racial hierarchy were more explicit. Architects at the time, including Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, credited types of architecture to specific racial aptitudes: Gothic architecture was a result of the Gallo-Roman’s “natural genius” and “supple and innovative natures,” he wrote, and “superior” Aryans had made the construction Ancient Greece possible by interbreeding with the Semites. His contemporaries not only posited that humanity co-existed on an evolutionary ladder, where non-white people invariably occupied the lower “primitive” rungs, architect Charles Garnier with historian Auguste Ammann actually ranked them in order. Their L’Habitation humaine exhibit at the 1889 Paris World Exposition lined reconstructions of homes from around the world from “primitive” to advanced, labeling the Chinese, Aztec, Inuit, and African as “Peoples Isolated from the General Movement of Humanity” who “did not exert any influence on the general advance of humanity.” For Cheng, “the message was clear.” She writes, “Some cultures were assigned to prehistory, or no history at all.”

Adolf Loos carried these sentiments of human hierarchy into the 20th century when he wrote Ornament and Crime, an essay that measured evolutionary progress through a culture’s erasure of ornament. According to his ranking, tattooed Papuans represented the unevolved lowest class while Germanic austerity represented the very top. “In the 20th century there will only be one culture dominating the globe,” he wrote — foreshadowing terrifying events that bring us back to Johnson.

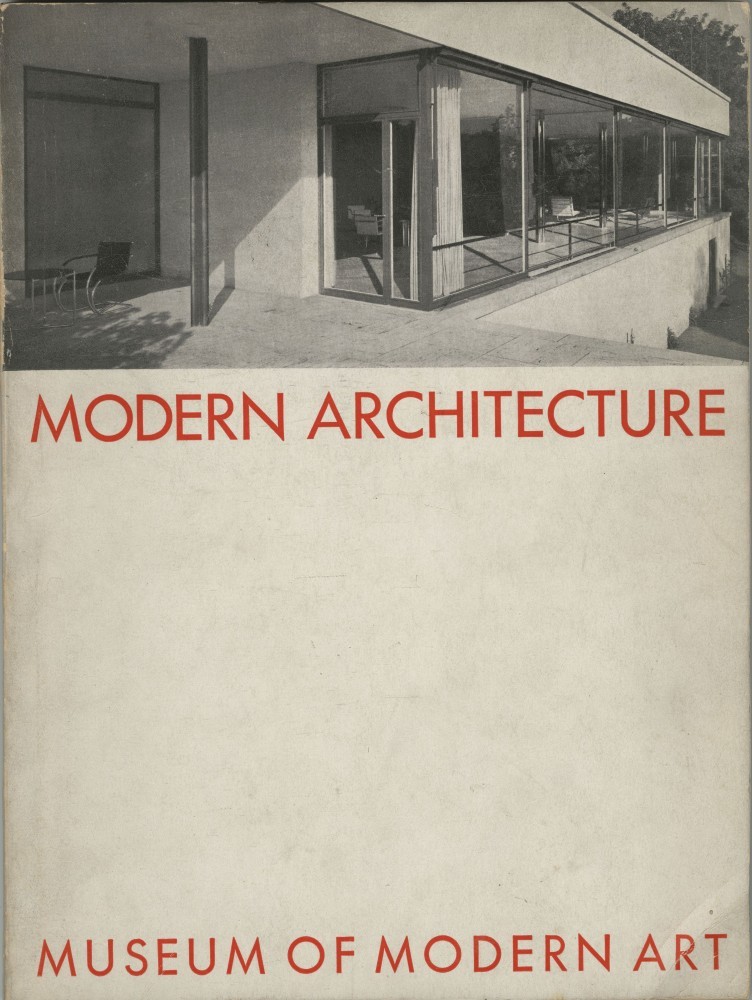

By the time the gospel of European Modernism reached American shores in 1932, in the form of Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock’s now-canonized MoMA show Modern Architecture: International Exhibition, these previously explicit racial hierarchies had quieted to a series of dog whistles. The show focused on 60-odd architects from Europe and the United States — in Johnson’s words, “the important countries of the world” — plus two Japanese architects and passing mention of North Africa’s influence on architect Jacobus Oud. Johnson and Hitchcock defined Modernism in terms of purity, refinement, cleanliness, and progress, naming German building as the “most consciously advanced.” The tacit implication there was that cultures that cherish the celebratory gestures of texture, ornament, and imprecision — cultures like mine — were therefore unimportant, unrefined, impure, and primitive. And despite the German Nationalist Socialist party’s objections to Modern architecture, Johnson felt at home with their ideologies, evidently sharing Loos’s belief that Germanic culture should dominate the globe. In October 1932, just months after the MoMA show ended, Johnson traveled to Potsdam to attend his first Hitler Youth rally.

The catalogue cover for the landmark show Modern Architecture: International Exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1932 curated by Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock. The exhibition’s framing of Modernism has been criticized as a subtle endorsement of white supremacy. © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.

The canon today, defining architecture as something so narrow as to exclude almost entire continents, seems to uphold Johnson’s and Kant’s belief that only the palest parts of the globe ever did anything worthwhile. “Architecture has been slow to interrogate itself,” Wilson tells me over the phone, describing the profession’s self-regard as “very future-oriented.” In its focus on inventing better homes and better cities, she explains, architecture’s perpetual boosterism maintains an essential distance from “the more problematic concepts, origins and methods” of the past.

I’ve felt this whenever I’ve asked about the white supremacist undertones of different aspects of Modernism, and my question was almost always dismissed as somehow rude, irrelevant, or strange. (Admittedly, I’ve internalized a lot of its narratives because it was the history we’ve been given.) I’ve imagined this is because in a mostly-white space like architecture (19th place on The Atlantic’s list of “The Whitest Jobs in America”), whiteness is very difficult to see; it’s frequently mistaken for neutral or universal, and the absence of color rarely comes to mind.

Citing architecture’s lack of its own Edward Said or Toni Morrison — celebrated figures who dismantled and reoriented the Eurocentrism of political science and literature, respectively — Race and Modern Architecture’s contributors have looked outside the limited narratives that the canon provides, using the works of W.E.B. Du Bois, Frantz Fanon, Cheryl Harris, and other critical theorists as a lens to analyze the architectural field. An interdisciplinary focus is necessary, explains Wilson, whose advisory committee for Reconstructions included poets, NAACP leaders, and elected officials. “If you really want to find evidence, traces, a sensibility of the inhabitation of Black space,” she points out, “you’re not going to find it in MoMA’s archives, right?”

There’s a certain fragility at work in the backlash against the Johnson Study Group, which suggests a striking similarity between architecture and any organized religion: In either, devout followers do not tolerate questions that threaten to undermine their faith. Race and Modern Architecture describes this tendency as a “misguided fear” that acknowledging an individual’s racism risks erasing them from history, but this is a total misunderstanding of the assignment.

Andrew Herscher’s chapter in Race and Modern Architecture cites bell hooks’s 1995 essay “Black Vernacular: Architecture as Cultural Practice,” another piece of required reading. In it, she posits that as a professional practice, one codified by a privileged class of the mostly-white, mostly-male, architecture is culturally and economically out of reach for most. In hooks’s more inclusive definition of architecture as a cultural practice, there’s room to celebrate the vernacular, the work of people like her grandfather, a southern sharecropper who creatively negotiated his own relationship with aesthetics and space. Herscher cites hooks’s call for a “subversive historiography,” the application of present knowledge to an embattled past, “thus creating spaces of possibility where the future can be imagined differently.”

hooks’s subversive historiography aligns with what both Race and Modern Architecture and the Johnson Study Group aim to do. The goal is not at all erasure, nor to broadly paint architecture as a racist profession. This is a call for a rereading, a revisitation of familiar passages in search of details we missed upon first pass. It’s the need to reevaluate and reassess previous generations’ ideas using our current knowledge, which incorporates the perspectives of those who were previously excluded from participating. Contrary to detractors’ fears, the confrontation of Johnson’s white supremacy is a call for more history, not less.

Text by Janelle Zara

Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present, edited By Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis II, Mabel O. Wilson (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020)