RECONSTRUCTIONS PORTRAIT: Sekou Cooke on Hip-Hop Architecture and Reconstruction

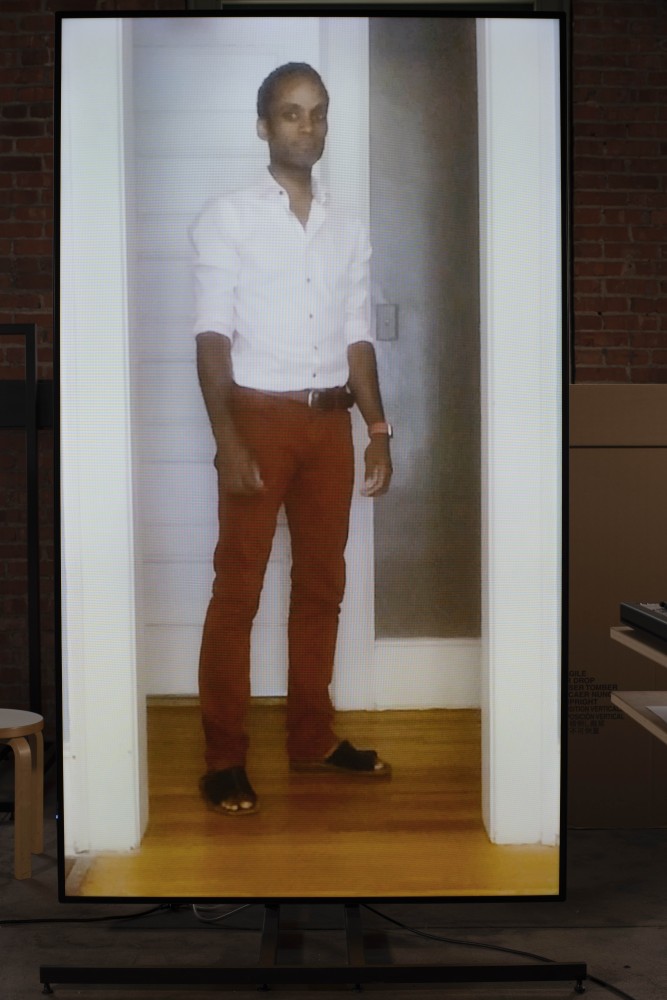

𝘖𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘰𝘤𝘤𝘢𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘰𝘧 Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America 𝘢𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘔𝘶𝘴𝘦𝘶𝘮 𝘰𝘧 𝘔𝘰𝘥𝘦𝘳𝘯 𝘈𝘳𝘵, 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗 𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘮𝘪𝘴𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯𝘦𝘥 𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘴𝘵 𝘋𝘢𝘷𝘪𝘥 𝘏𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘤𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘵𝘦 𝘷𝘪𝘥𝘦𝘰 𝘱𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘩𝘰𝘸’𝘴 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘢𝘳𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘵𝘦𝘤𝘵𝘴, 𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘴𝘵𝘴, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘥𝘦𝘴𝘪𝘨𝘯𝘦𝘳𝘴. 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘵𝘦𝘯 𝘱𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘴 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘢𝘤𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘱𝘢𝘯𝘪𝘦𝘥 𝘣𝘺 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘷𝘪𝘦𝘸𝘴 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘦𝘢𝘤𝘩 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘢𝘯𝘵 (𝘴𝘦𝘦 𝘣𝘦𝘭𝘰𝘸). 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗’𝘴 𝘙𝘦𝘤𝘰𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘳𝘶𝘤𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘚𝘱𝘦𝘤𝘪𝘢𝘭 𝘦𝘥𝘪𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘪𝘴 𝘢𝘭𝘴𝘰 𝘢𝘷𝘢𝘪𝘭𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦 𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦. 𝘈 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘯𝘦𝘳𝘴𝘩𝘪𝘱 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘛𝘩𝘰𝘮 𝘉𝘳𝘰𝘸𝘯𝘦.

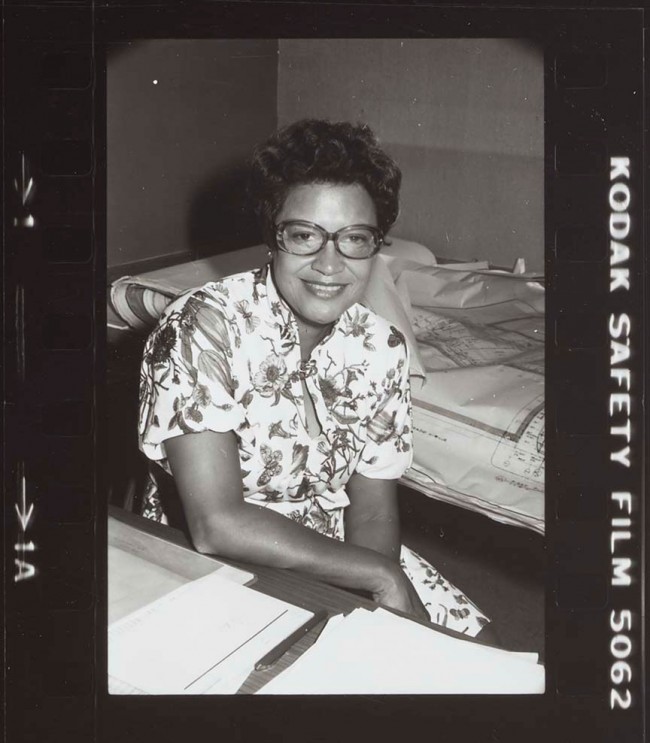

Sekou Cooke is a Jamaican-born, Syracuse-based architect, curator, and educator. The founder of sekou cooke STUDIO and Assistant Professor at Syracuse University School of Architecture, Cooke is perhaps best known for his research and exhibitions on the emerging field of Hip-Hop Architecture, which excavate the architectural impact of hip-hop and its culture while proposing design practices that embody expressions and knowledges from beyond the ivory tower.

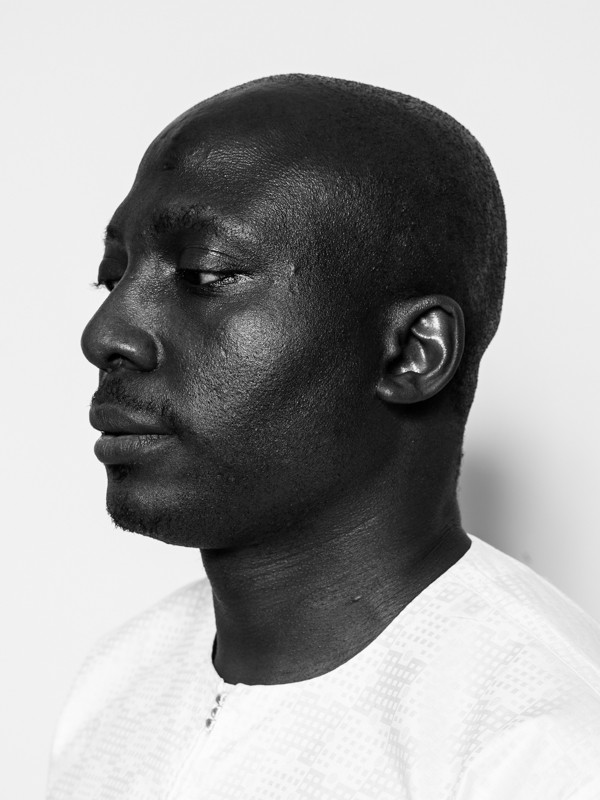

Sekou Cooke photographed by David Hartt for PIN-UP.

PIN–UP: What led you to architecture?

Sekou Cooke: I’m one of those rare creatures who, for some reason, decided that I wanted to be an architect when I was five years old. It had something to do with me drawing a lot and taking all my toys apart to see how they were put together. I do remember my grandmother talking about these people who draw buildings for a living and thinking that sounded like fun. My older sister, however, was really the one who paved the way for me. Though she didn’t decide to study architecture until her last year of high school, her path from City College in New York to Cornell helped show me what was possible. I’ve told the story many times about how she literally filled out my application for me, photographed the work for my portfolio, and talked to Dr. Ray Dalton, then director of the Office of Minority Educational Affairs, about my application to make sure I got into Cornell.

Once I got there, I realized I really had no idea what architecture was, but these people were my people. Studying architecture challenged me in a way nothing else had up to that point, so I knew I was in the right place. I’m still trying to figure out what architecture is.

How has your practice evolved?

My practice today looks almost nothing like it did 20 years ago, or ten years ago, or even five years ago, with the exception that I’ve always focused on getting my work built. This, to me, has always been the distinguishing factor between academics and practitioners. Now that I’m more deeply involved with academia, I’m still just as committed to getting work built, but I’m now also committed to having a clear theoretical basis for the work that I do. That, of course, means that there needs to be several years of investment into a topic before its ideas can be properly tested in the real world. Fortunately, I’ve had more and more opportunity to test some of these theories in my practice. The main subject I’ve been researching over the last six years has been Hip-Hop Architecture, an architectural movement aimed at transmuting hip-hop culture into built form. I have been finding its origins, identifying its practitioners, and speculating on how it might transform the discipline of architecture. This work has led to a much more robust profile as a curator and theorist in academic circles. It has also, more recently, begun to shift the work that has been coming into my professional practice. The Close to the Edge exhibitions in New York (Center for Architecture, 2018) and St. Paul, Minnesota (SpringBOX, 2019) were not just curatorial exercises but also design products that can be considered Hip-Hop Architecture. I’ve also been working on a project for The Good Life Foundation in Syracuse to turn an abandoned warehouse building into the Syracuse Hip-Hop Headquarters. There are other hip-hop-based projects in the works as well that have yet to be made public.

What does “reconstructions” mean to you? Both as the title of the show and as a historical or contemporary reference?

I think the work of Reconstructions is a 150-year ongoing project. We’re still, as a nation, not quite sure what to do to repair the damage begun over 400 years ago. Each attempt at reconstructing the relationship between America and its Black citizens has been mostly ceremonial and ultimately toothless. Much like the various treaties signed between our government and the indigenous nations that were here long before them, every single promise has been violated. But, for some reason, we continue to hope. This is why we continue to protest and strategize and struggle and compromise — because we believe change can and will come. This is why I believe we formed the Black Reconstruction Collective: to take advantage of the opportunity afforded by the MoMA to spotlight and to continue the unfinished work of reconstruction, particularly in the architecture and design fields. In addition to the general mystery surrounding architecture — what architects do, what our value is to society — there is an almost complete lack of understanding or awareness of just how few Black architects there are. We are struggling to find relevance in a field that itself is struggling to find relevance. The Black Reconstruction Collective can become a powerful vehicle for elevating and amplifying the work of Black architects and designers, bringing them into a long-awaited spotlight. In this way, the work I’ve done on Hip-Hop Architecture shares a common mission with the collective.

Can you describe the project you’re creating in response to the MoMA Reconstructions brief? Where is it and why did you choose that location?

I’ve decided to focus on Syracuse, mostly because I don’t think we have to look far past our own backyards to find challenges to tackle. This was a city I had to make an argument for since it wasn’t on the original list. But once I explained its history of marginalizing and continually displacing and replacing its Black residents, and its imminent repetition of those same patterns with the planned demolition of Interstate 81 and redevelopment of its public-housing projects, it was hard for the curators to say no. My research into the demolition of the old 15th Ward in the 1960s (then a predominantly Black neighborhood), the 1940s Pioneer Homes housing project in Syracuse’s South Side, and the current Blueprint 15 project to tear down Pioneer and other Syracuse housing projects revealed a multi-textured, multi-layered built history within a very concentrated area of the city. My project takes those layers, samples them, remixes them, and lays them back on top of an imagined projection for the area’s future. It turns a development — projected to be a typically banal internally-focused housing project — into an externally-focused image of public space for the Black community. We Outchea, as I’ve titled it, leverages contemporary narratives of mostly criminalized activity of Black people in public spaces to create a visual dialogue with the new housing proposal.

Interview by Drew Zeiba

Video portrait by David Hartt

Editing by Jessica Lin

Music by King Britt presents Moksha Black

A PIN–UP production in partnership with Thom Browne

This video is part of a series of ten portraits David Hartt created for PIN–UP on the occasion of Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America at the Museum of Art (Feb 20–May 31, 2021), curated by Mabel O. Wilson and Sean Anderson. The portraits were also published in the print edition of PIN–UP 29.