FOLKS ON CHAIRS: African-American Home Life As Seen Through the Lens of Art

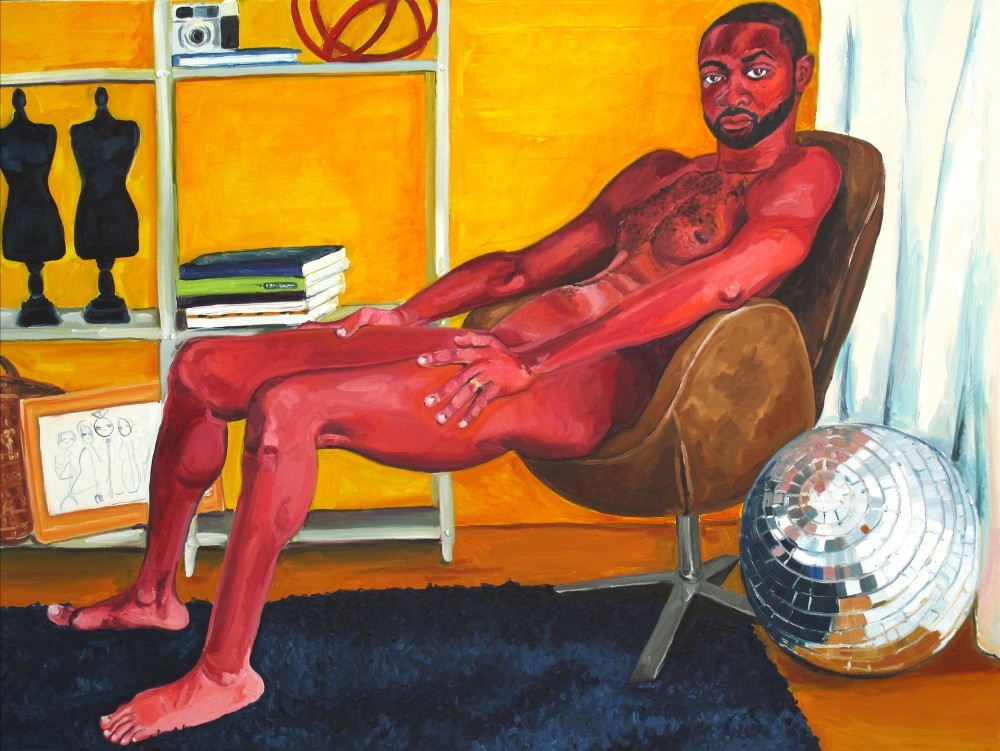

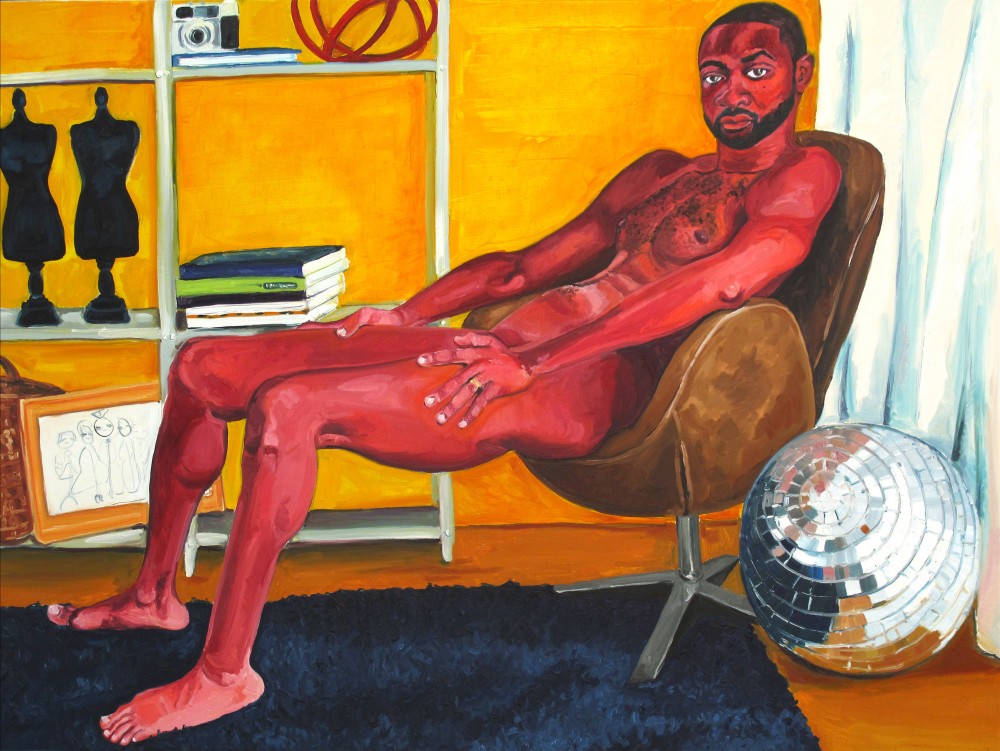

Jordan Casteel, Sterling (2014); Oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the artist and Sargent’s Daughters.

Our Americanness has beset us with a peculiar set of obsessions and generalized characteristics that define our unique and young history as a people. It includes the belief in American exceptionalism, a Blanche DuBois-like condition of denial, a fanatical preoccupation with leisure, and an overzealous attachment to consumerism. But America’s particularly oppressive preoccupation with race tops my list of these cultural markers. It has saddled us with a fractured understanding of and relationship with the richly varied lived experiences of people from the African diaspora and more specifically African Americans. Until recently, this anthropological blind spot was neatly and securely maintained in conventional art, architecture, and design history. The shedding of this cloaked and muted prejudice is essential to the process of realizing equity and equality within a shared society.

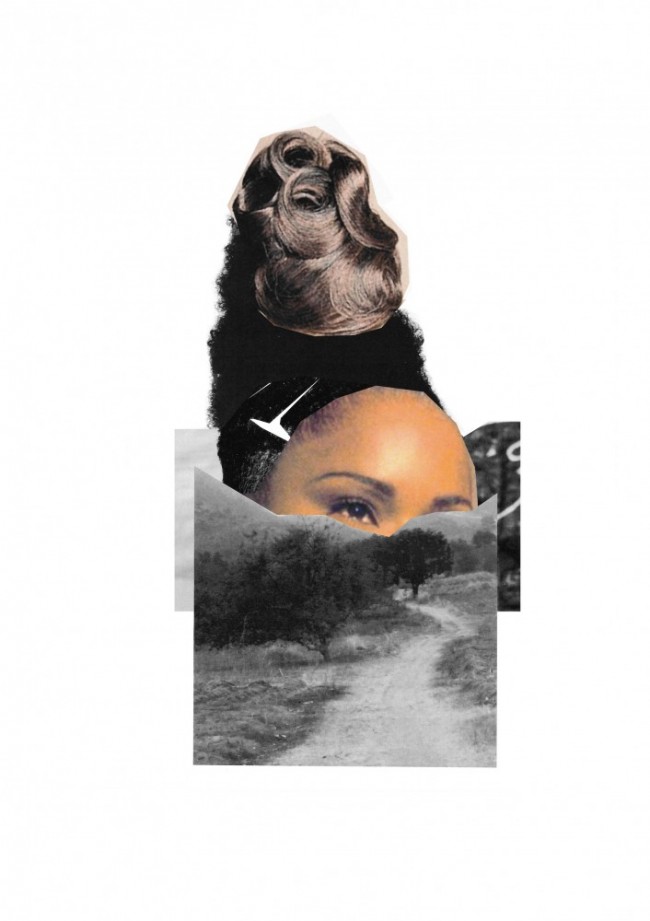

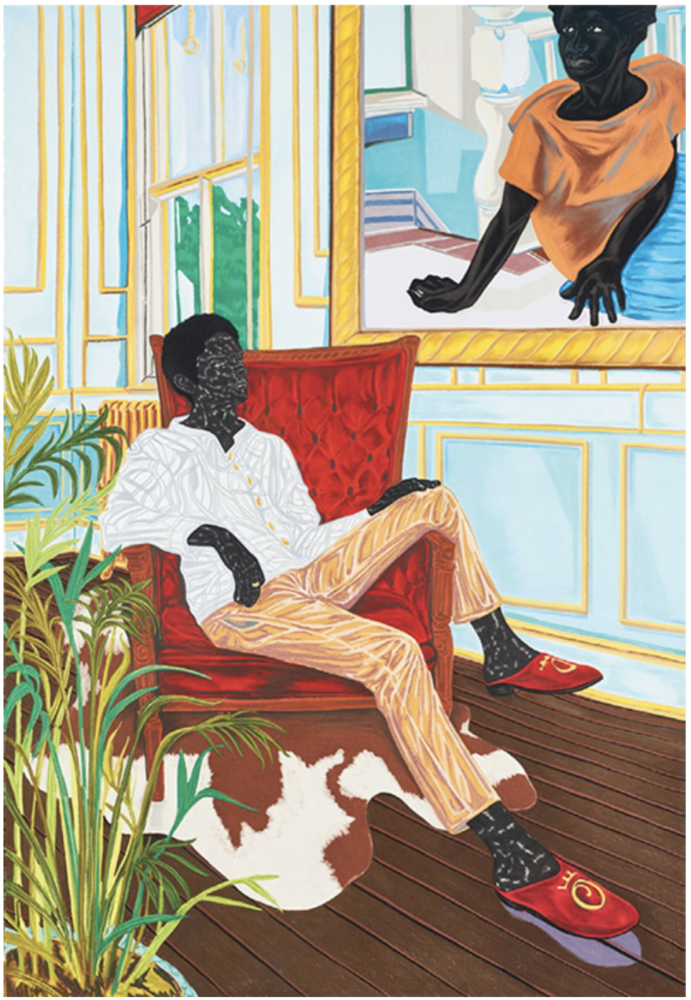

Toyin Ojih Odutola, A Grand Inheritance (2016); Charcoal, pastel, and pencil on paper. © Toyin Ojih Odutola. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

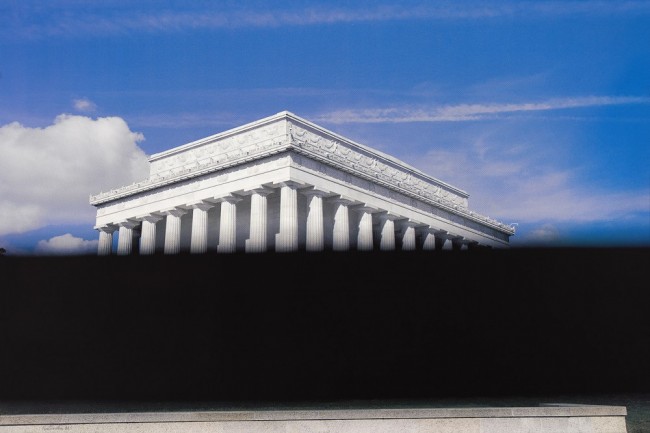

One can’t discuss African-American homes without taking into consideration the post-emancipation crusade to prevent black and white Americans from living in close proximity to each other. The result was over a century of either state- or self-imposed segregation that often continues to this day. Where housing was concerned, the creation of suburbs and incentivized opportunities for white home ownership through the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, rules of block-by-block racial percentage, zoning laws, and an army of realtors complicit in the enactment of separation laid the foundation for unequal living conditions, social alienation, and the invisibility of the African-American middle class. These practices were upheld in law for over a century, from the 1866 Civil Rights Act until the 1968 Supreme Court ruling on the case of Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Company, which declared once and for all that racial barriers to the acquisition of property were “badges and incidents of slavery.”

-

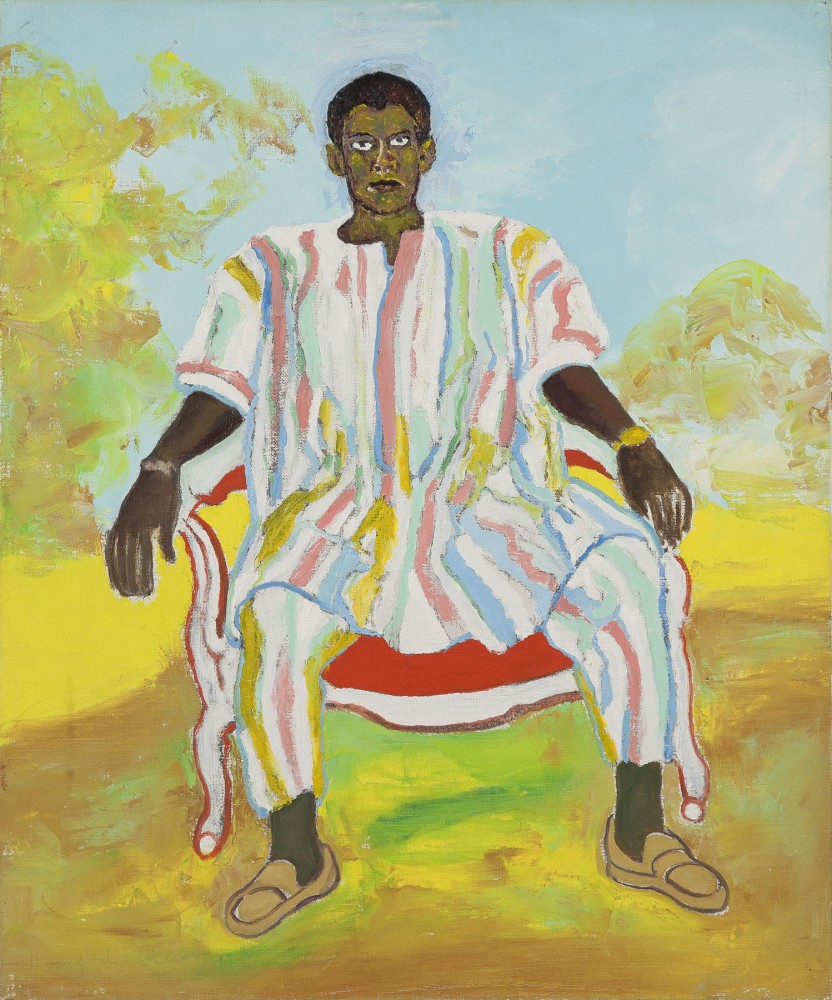

Jennifer Packer, Tobi (2012); Oil on Canvas. Courtesy of the artist, Corvi-Mora, London & Sikkema/Jenkins, New York.

-

Henry Taylor, The “We” Hours (2012); Acrylic on canvas. © Henry Taylor. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo.

The legacy of these practices is still playing out today in racial income inequality and the social strife imposed by gentrification. If the color of a room or the shape of a window can change how we feel, the psychological trauma of a harsh and uncontrollable environment is undeniable. In his 2006 book The Architecture of Happiness, Alain de Botton writes:

“It is to prevent the possibility of permanent anguish that we can be led to shut our eyes to most of what is around us, for we are never far from damp stains, cracked ceilings, shattered cities, and rusting dockyards. We can’t remain sensitive indefinitely to environments which we don’t have the means to alter for good. We end up as conscious as we can afford to be.”

Njideka Akunyili Crosby, And We Begin to Let Go (2013); Acrylic, charcoal, pastel, marble dust, collage, and Xerox transfers on paper. © Njideka Akunyili Crosby. Courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

A more subtle consequence of separation and marginalization is a lack of connection to African-American home life, the invisibility of our diversity, complexity, and humanity, an unfamiliarity with the interiors that reflect these varied aesthetics. This void remained largely intact until the 1970s, when progressive television producers such as Norman Lear started telling more nuanced stories of American life. He brought the public into the homes of The Jeffersons (1975–85), Florida and James Evans (Good Times, 1974–79), and Fred Sanford (Sanford and Son, 1972–77), which spanned the African-American class strata. The 80s brought us The Cosby Show (1984–92), featuring an upwardly mobile family whose life was an authentic representation of an African-American upper-middle-class aesthetic. Its legendary success provided a benchmark for the interior-design aspirations of many, highlighting the malfeasance of underrepresentation in such a public forum as television, not to mention the design industries.

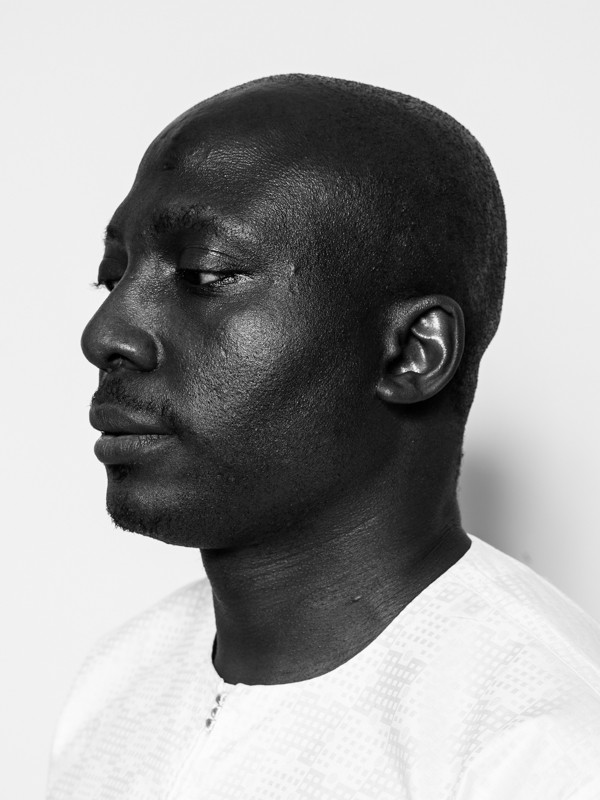

Beauford Delaney (1901-1979), Man in African Dress (c.1972); Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY. Estate Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator.

Yet still today the results of an extensive Internet search for visual evidence of the interior lives of African-American icons is lackluster at best. Instead, the images I sought out began to unfold in the works and ruminations of the paintings I loved. Created by black artists who were either born in or immigrated to the United States, they imagine, dissect, and lay bare the infinite layers of the African-American experience. Works by Beauford Delaney, Barkley L. Hendricks, Kerry James Marshall, Kehinde Wiley, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Jordan Casteel, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Jennifer Packer, and others provide the perfect portal through which to explore ideas about aesthetics, imagination, and freedom. Recalling the first time she saw Kerry James Marshall’s painting Souvenir (1997), Naomi Beckwith, Senior Curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, describes a powerful reaction:

“It stopped me dead in my tracks. There in the painting, staring at me, was an ebony angel, busy keeping house in what was almost a faithful rendition of my grandmother’s living room. It was both realist and surreal, at the same time. I had no plans to be a curator at that age nor did I know who Marshall was, but I thought, ‘This is a painter who knows my life and my black history and committed it to art history.’ Marshall captured the tone and decorative sensibility of the (Chicago) South Side middle class, right down to the potted plants and decorative birds ... (His) painting was the first I saw that made me feel that art understood me in return.”

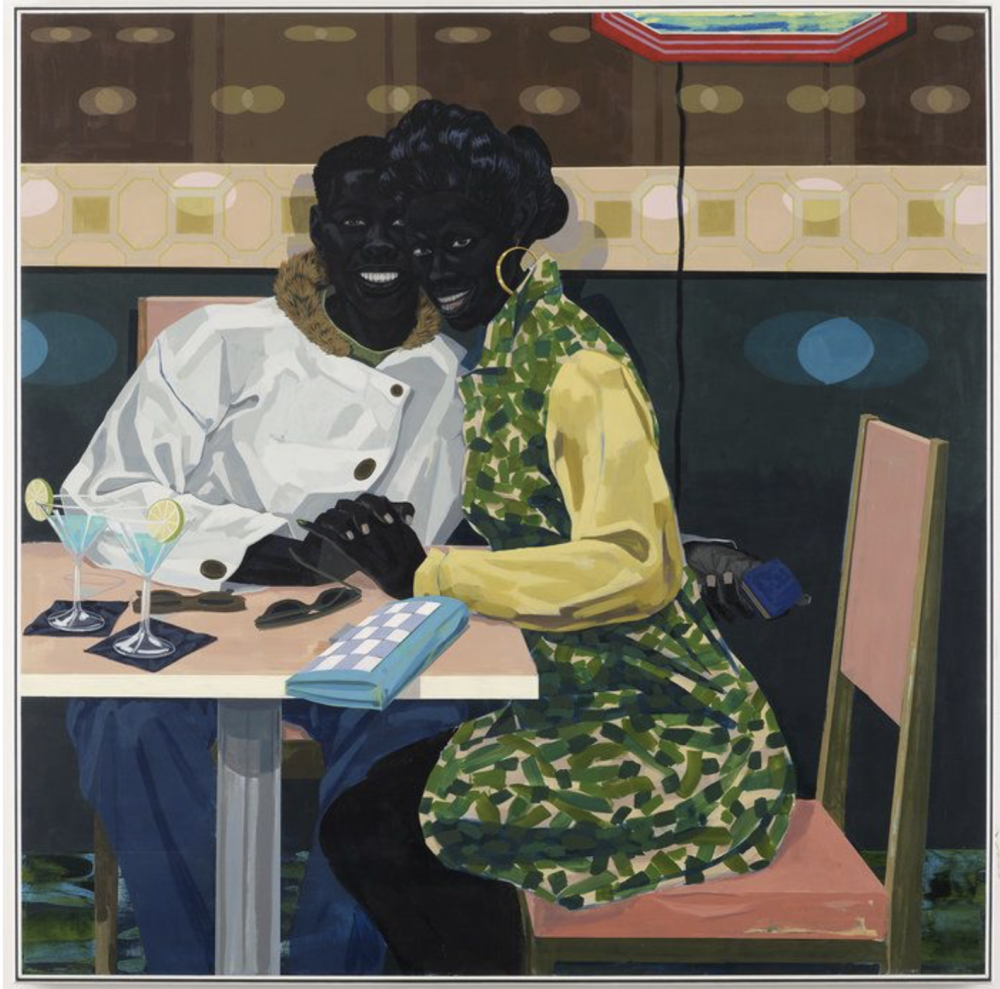

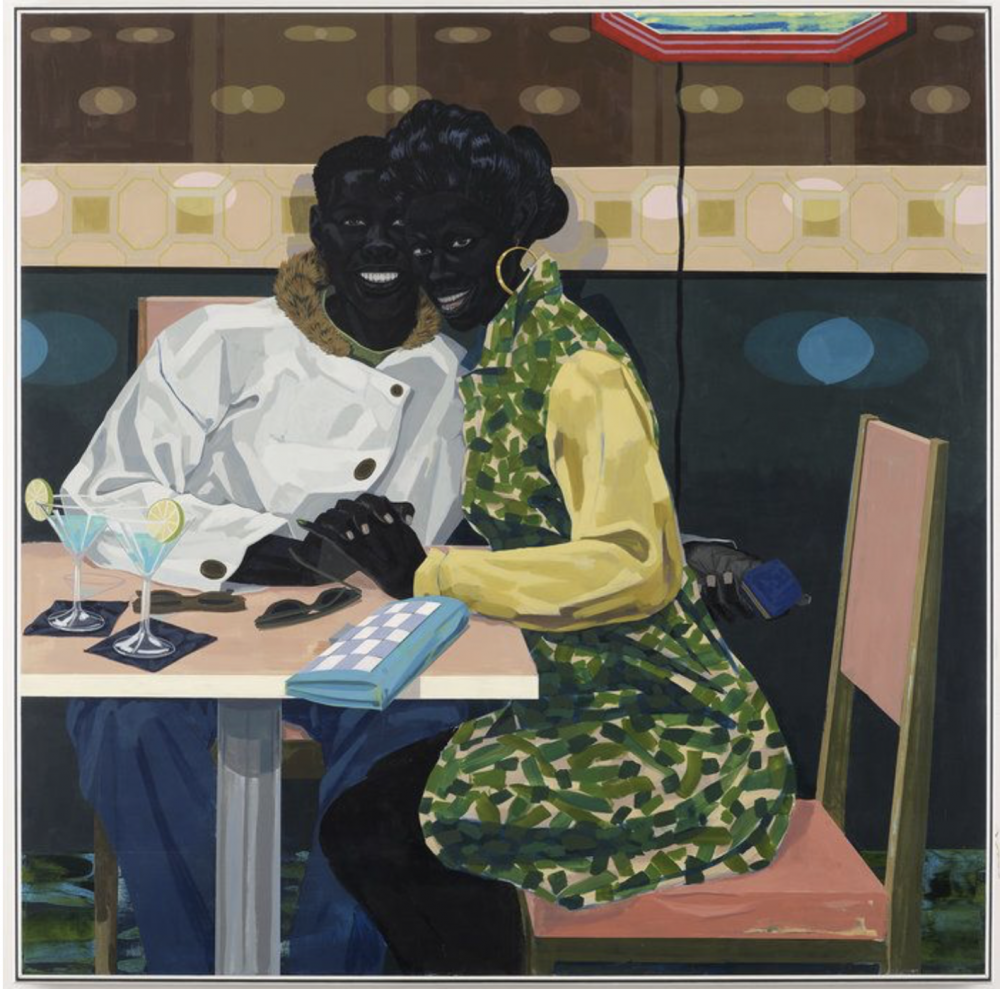

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Club Couple) (2014); Acrylic on PVC panel. © Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

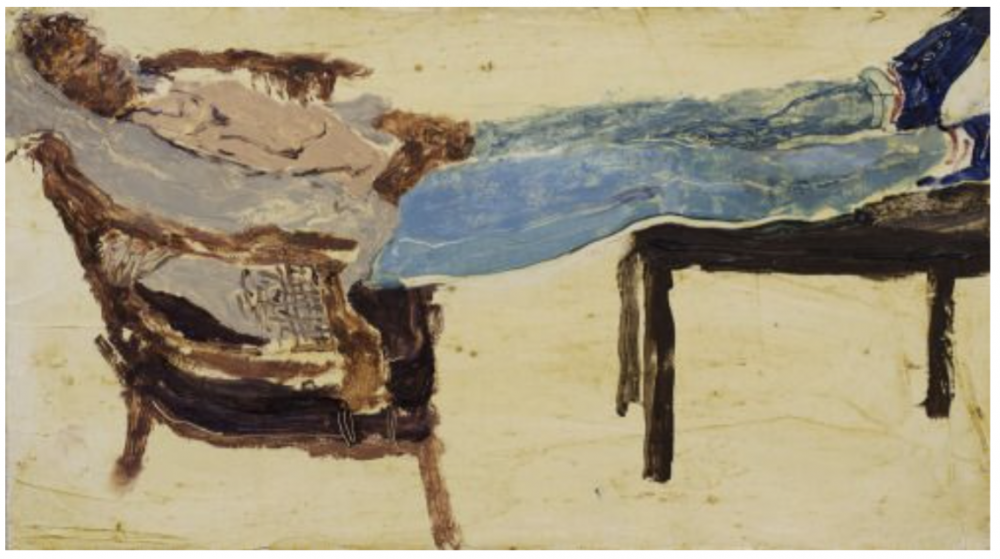

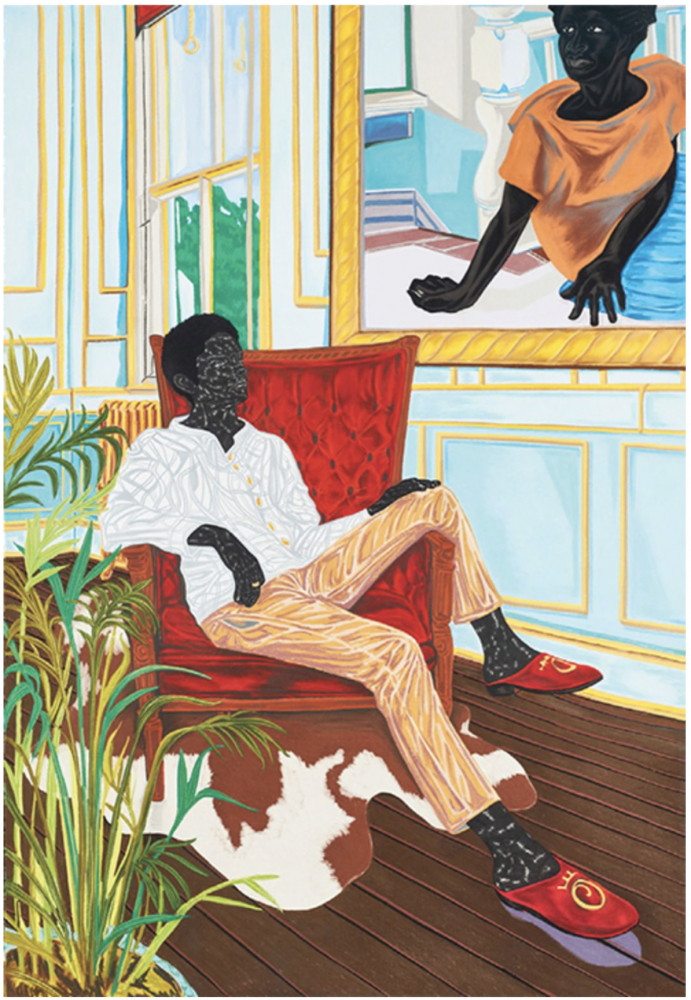

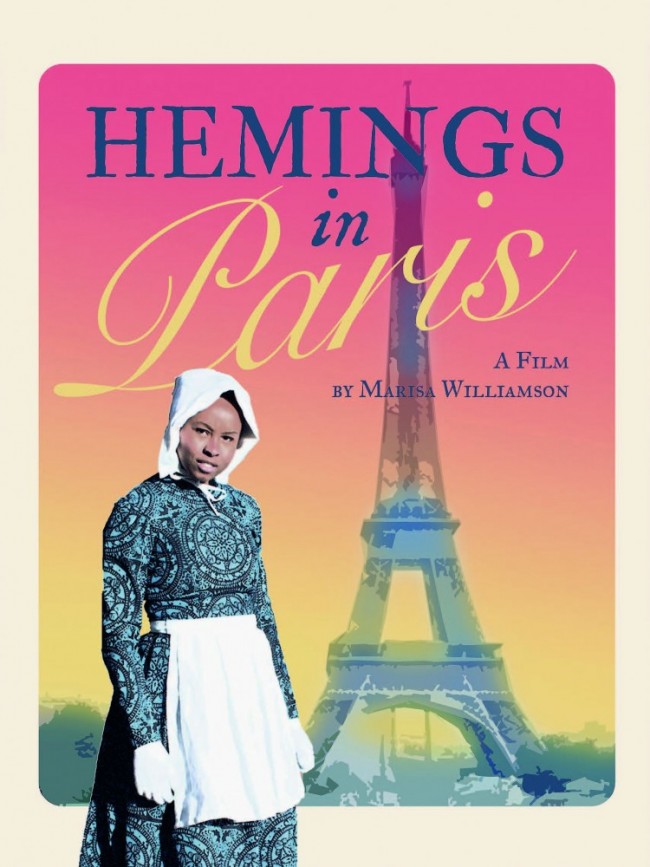

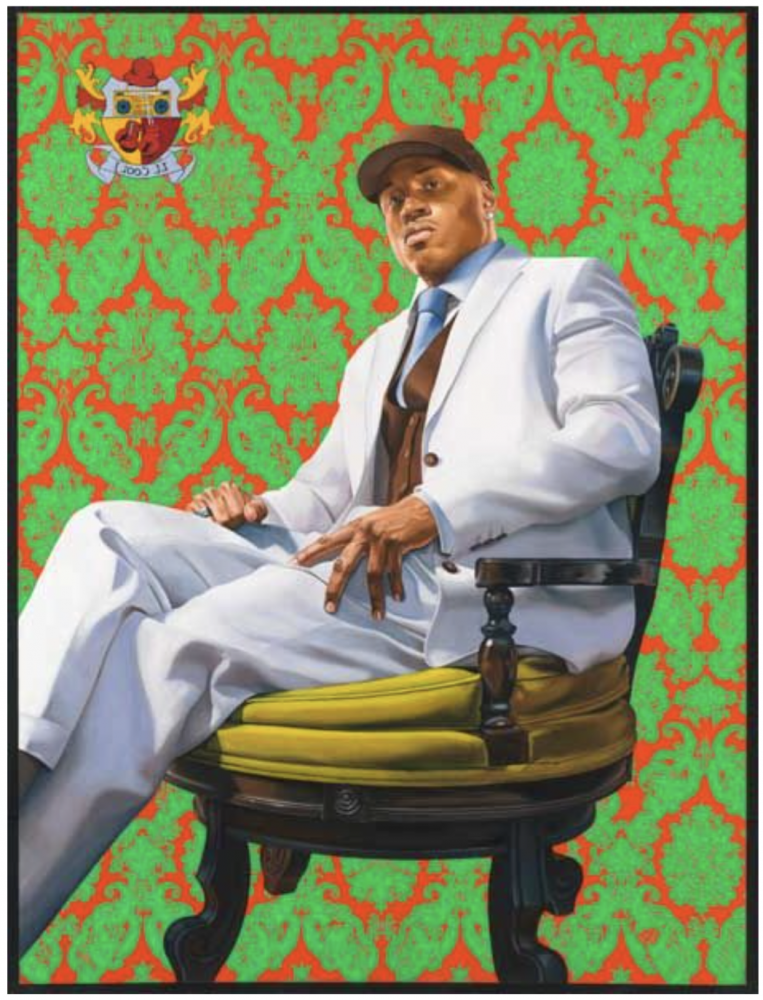

Upon closer examination of the works shown on these pages, we see that the artists who made them deploy conviction, meaning, and purpose by using quietly everyday objects to anchor the story with a mood, thereby setting the stage for the feelings conveyed. And often it’s that most elemental of design objects, the chair, which acts as the anchoring element. Exploring color and implied materiality, one can connect with the simple sweet joy of the moment in Marshall’s Untitled (Club Couple) (2014), where the chairs that hold the pair in their pre-proposal moment of bliss are simple wooden structures painted in the most tender of pinks. A Grand Inheritance (2016), a painting by Toyin Ojih Odutola, a Nigerian artist who lives in New York, portrays a young man of stature slouched in a bright-red, button-tufted, Victorian-era wingback chair. An indoor plant and wood-paneled walls suggest the coded ease of a well-appointed bourgeois home. But beyond the obvious connotations of class and ideas of good taste, Odutola also makes direct and ambiguous reference to Marshall’s SOB, SOB (2003), part of which fills the upper right corner of her work. A rattan chair, the wingback’s outdoor sibling, lodges itself in the viewer’s memory of the work of another Nigerian artist, Njideka Akunyili Crosby. In her complex and culturally melodic environments, furniture always takes center stage, drawing the viewer into her transnational experience as someone raised in Nigeria and living in Los Angeles. The languishing interior lives of folks waiting for the day to pass are best captured by American painter Henry Taylor: the three putrid-looking chairs in his painting The “We” Hours (2012) seem to have seen better days, reeking of utility and lost hope. Whether we’ve seen it or experienced it, there is a type of listless sadness that only a worn chair can convey. Meanwhile, Jordan Casteel’s Sterling (2014) offers an alternative to this malaise: Arne Jacobsen’s celebrated 1958 Swan chair is the supporting actor in this story (along with a silver disco ball), and its presence is second only to the subject’s vibrant red skin and confident gaze. The subject — Sterling — owns his future and his space.

Kehinde Wiley, LL Cool J (2005); Oil on canvas. © Kehinde Wiley. Courtesy: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Considering all that is required to achieve a humane and equitable society, interiors and their contents, especially chairs, might seem like a trivial vehicle for investigating the effects of a racialized society. But when you consider chairs as portals for socio-economic conditions, ceremony, and history, and the many reasons to sit on them, they turn out to be very powerful objects through which one may recount hitherto-untold stories.

Text by Tiana Webb Evans.

Taken from PIN–UP 25 Fall Winter 2018/19.