INTERVIEW: Controversial London Architect Amin Taha Rings In A New Stone Age

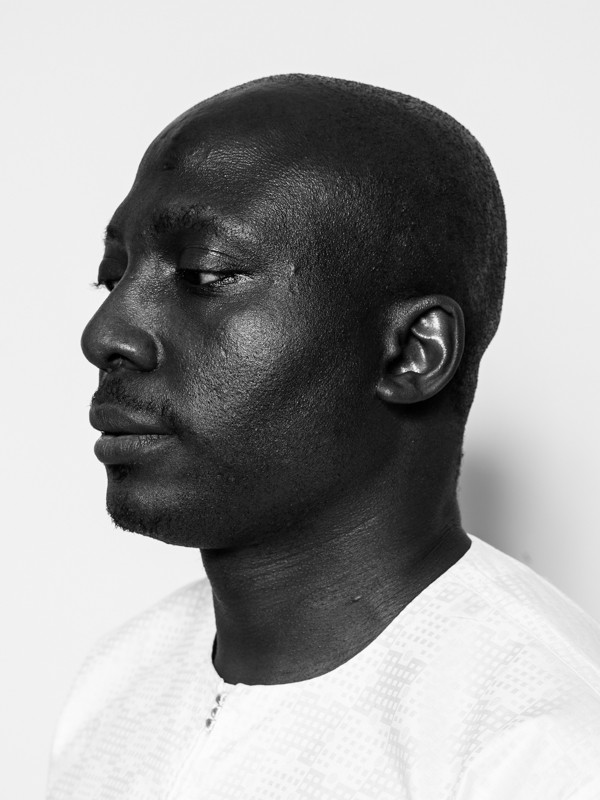

Award-winning British architect Amin Taha was born in the mid-1960s in East Berlin. His parents had moved to the Communist East German capital to study medicine, escaping their respective home countries, Iraq and Sudan, after revolutions shook up the regimes at home. In the 70s, the family settled in the U.K. where Taha studied architecture and later started the firm Groupwork, an employee ownership trust of which Taha is now the chair. Since Groupwork’s founding in 2003, Taha has also earned a reputation as “London’s most controversial architect” (Financial Times). The reason for the polemic is 15 Clerkenwell Close, a building in central London which contains both Groupwork’s office and Taha’s own apartment. On completion three years ago, 15 Clerkenwell Close hit the headlines when it was issued with a demolition order by Islington Council for non-conformity with the submitted plans. It turned out that aesthetics were the real reason behind the authorities’ doggedness, certain councilors violently objecting to the presence of a loadbearing and sometimes roughhewn limestone exoskeleton façade in a historic conservation area. Groupwork eventually won at appeal, but the whole affair left a sour taste. Many, including Taha, were reminded of Prince Charles’s infamous 1984 “carbuncle” speech, in which the heir of the throne publicly attacked contemporary architecture. The sterile “beauty” debate that ensued continues to bedevil British architecture to this day. PIN–UP met with Taha at Clerkenwell Close, the scene of the alleged crime.

Greenery starts to take hold on the raw limestone façade of 15 Clerkenwell Close, designed by British architect Amin Taha. The building’s masonry references an 11th-century limestone abbey which previously stood on the site.

Andrew Ayers: This is PIN–UP’s REVOLUTION issue. And I believe your background might be described as revolutionary.

Amin Taha: My parents left post-colonial Iraq and Sudan saying, “We’re going to join the ideal!” They were 16. Both sets of grandparents were like, “What the hell are you doing?!” My mother was a communist, her brother was a nationalist, the same with my father’s family — the sibling rivalry expressed itself politically. In Iraq, a government and a royal family had been set up by the departing British, but in 1958 there was a revolution, the socialists took over, and after that the Eastern Bloc came in and said, “Send your kids to be educated here! We’ll send them back and they’ll run the country and we’ll all be socialists together!” And so off my mother went to East Germany to study medicine, where she met my father. Then, in 1963, there was a counterrevolution in Iraq, which her brother took part in as a member of the nationalist party. He warned her, “We’re shooting all the communists to avoid another revolution. It’s better if you don’t come back!”

And your father?

He came from Sudan, where it was all very similar to my mother’s situation. So together they were marooned in East Berlin and could never return until things changed. And they never really did change. They ended up visiting the U.K. because they had relatives here, who suggested, “They need doctors in Britain, why don’t you come?” Which they did, when I was eight.

You definitely seem to be channeling your parents’ spirit of idealism in the way you’ve set up your firm, Groupwork, as an employee ownership trust. Can you explain how that works?

Under U.K. law, an employee ownership trust means that anybody who stays at Groupwork for 18 months automatically becomes an equal partner. The trust has to have a chairperson, and because I set it up some time ago and I’m the eldest, I was elected chairman. I haven’t yet done what any good dictator should, and made myself chairman for life, so one day I might get so old, belligerent, and just not with-it that I’ll be voted off. (Laughs.)

Amin Taha seen watering the roof garden at 15 Clerkenwell Close. Photographed by Harry Mitchell for PIN–UP.

What made you want to set up the firm this way?

When you have an eponymous firm with a named leader, it becomes a sort of co-dependency. I’ve worked for some of those offices (Zaha Hadid and WilkinsonEyre among them). That leader becomes slightly autocratic, with a dynamic building up where they’re the figurehead, and you end up wanting them to be the figurehead and to tell you what to do and guide the group. But they can’t do it all, they don’t want to do it all, and sometimes they get frustrated because the skewed dynamic means that not enough people are voicing their opinions. And the very successful practices are all about debate — ideas are proposed and debated, and if you’re any good as a figurehead you can see and use good ideas, and not, through some other motivation, overrule them. However, what tends to happen is that people spend years in these practices and never get any recognition and ultimately don’t financially benefit: they’re not locked in in such a way that their motivations for guiding the practice are long-term — for their own benefit, the projects’ benefit, and the practice’s benefit. So that’s why I felt the equality of a trust was the best solution.

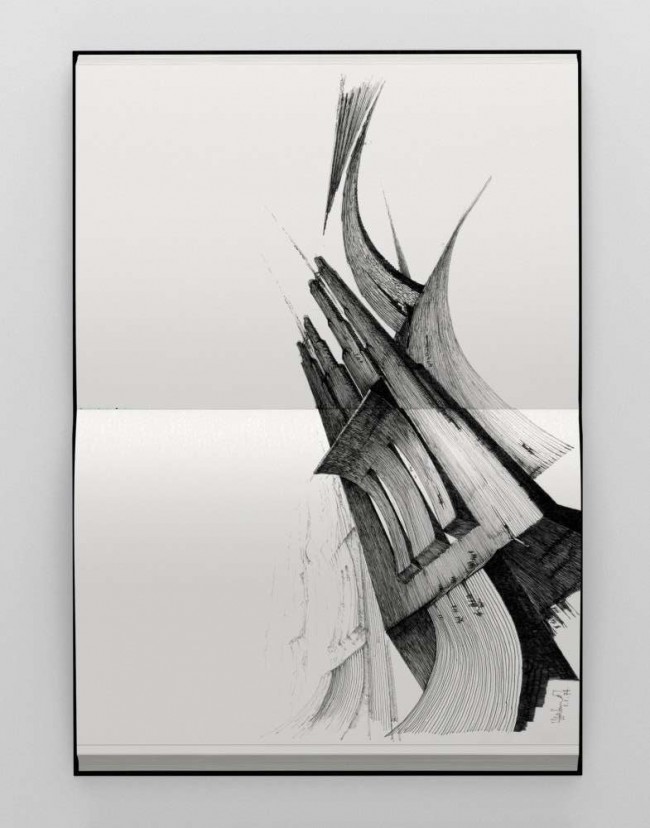

You’re also attempting to change, or perhaps even revolutionize, the way buildings are constructed through a return to essentials and a focus on tectonics. How did this approach evolve?

When I lecture to students, I sort of jokingly answer that it came from being lazy. I describe it with two slides, and I use Clerkenwell Close as an example. With the first slide I show what is pretty much the standard way all over the world of putting up a stone-fronted building: a steel or concrete frame, which has to be fireproofed and waterproofed, insulated against the weather, has to have a vapor barrier on the other side of that insulation. You then have to pierce all that with steel clamps that go through to the frame, they then have to have another clamp that’s bonded to the stone veneer, and then all that has to be weatherproofed and all the rest of it. There are multiple levels of detail there, and multiple separate procurements, subcontractors, and trades. It’s all very well, you can draw it, but what tends to happen is that, oh, the client changes their mind, or something occurs where you have to move a window or a door. Every time you do that, you have to redesign and redraw everything I’ve just described. And if you don’t, and leave it to a subcontractor to sort out, you’ll inevitably end up with problems you’ll have to answer for, sometimes legally. So what if you do the lazy thing and say, “Instead of all those different trades, instead of all those different layers of drawing, why not get two or three materials to do the whole lot?”

Amin Taha designed 15 Clerkenwell Close in London to house his apartment and the office for Groupwork, the architecture practice he established in 2003. Upon its completion in 2017, the building caused controversy and the local council ordered demolition. While the dispute was eventually resolved, the episode spotlighted Taha’s unique and cost-effective design: the building’s rough-hewn masonry is not merely decorative but a load-bearing exoskeleton.

I presume there are also sound environmental reasons for working with less materials?

Yes, one of the reasons we used a stone exoskeleton in Clerkenwell was for reasons of sustainability, since it has ten percent of the carbon footprint of a steel or concrete frame. But it’s also cheaper and quicker to build in stone. There’s an ethical dimension to this approach: you’re using fewer resources, your carbon footprint is lower, but you’re also saving your client money — up to 25 percent if you’re using stone in an area where the material is readily available. We’re currently working on a country house in Oxfordshire, and we’re experimenting with both stone and timber to see whether it’s possible to be carbon negative, and if so what form that might take. Will we actually need any cement or concrete at all, or can the whole thing can be done in just stone, including below-ground areas?

Have you found the answer yet?

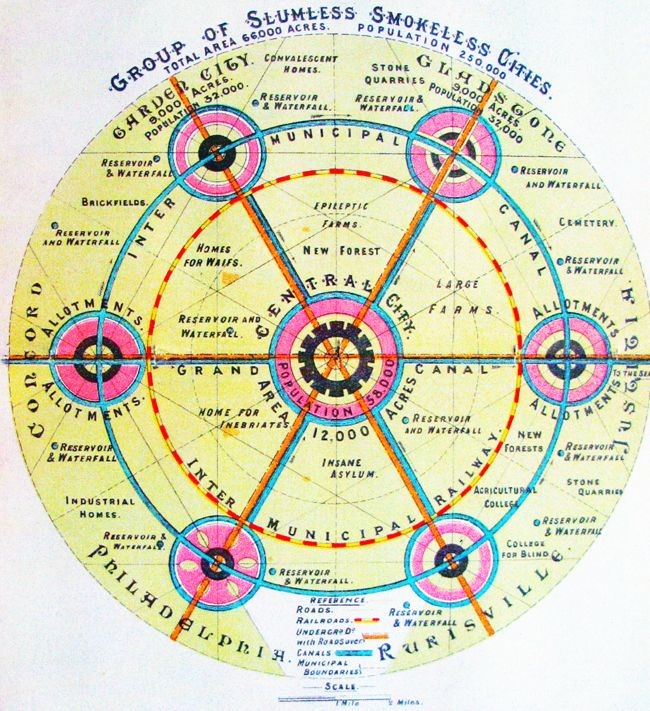

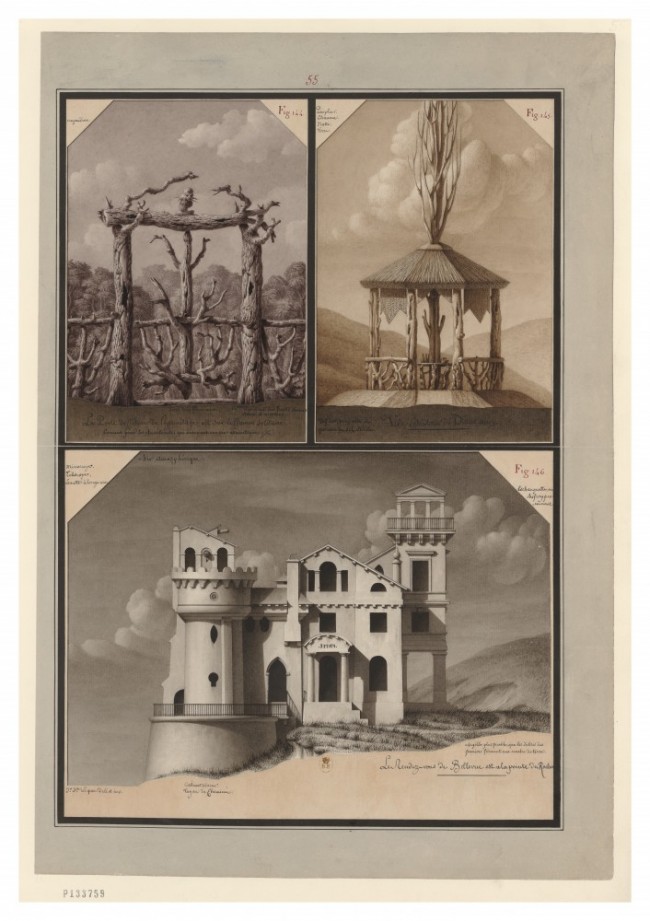

It certainly was done in the past; I don’t see why it wouldn’t be possible. I recently co-curated an exhibition at London’s Building Centre called The New Stone Age. One of the places we looked at was post-war Marseille, where obviously you have Le Corbusier building his famous Cité radieuse (1949–52) in what was considered the material of modernity, reinforced concrete, but also at exactly the same time you have Fernand Pouillon rebuilding the Vieux Port (1947–56) in loadbearing, regionally-quarried stone. So our argument was that Pouillon might have been right in terms of being able to do mass housing inexpensively, because basically he and his stonemasons said, “We can cut blocks of stone of a certain size out of the quarry, they’re easy to transport and handle for buildings of a certain height, they can be assembled without all the water you use for concrete, which means the building can go up inexpensively and quickly.” And so they kept on winning tenders that way. Whereas doing things in reinforced concrete was a new and more expensive technology at that time, but it was a period when fuel and energy consumption and carbon emissions weren’t key issues, but being modern, and emblematic of the modern, most definitely were. To somebody of our parents’ generation or older, building in stone would have seemed retrograde: “That’s the old world — why on earth would you want to build the old way?”

Barretts Grove stands tall between a Victorian townhouse and Edwardian primary school, its red bricks and gabled roof echoing the North London neighborhood’s familiar forms. At the same time the wicker balconies and brick roof signal an unconventional take on these archetypes. Architect Amin Taha opted not to seal the bricks which envelope the entire structure, making explicit that the brickwork is a rain screen not a load-bearing superstructure.

Have attitudes now changed to being in favor again of building with stone?

Yes, there’s a return to stone for all sorts of reasons, for sustainability but also for cost. We did an analysis to see if it might be cheaper and quicker to build in loadbearing stone even up to 30 stories. And it turns out that it is, at least in the U.K. We thought we were being ambitious with 30 stories, but as it happens the French architect Gilles Perraudin had already designed a 20-story mixed-used tower for a site in Geneva using a lot of loadbearing stone. So we realized that actually we hadn’t been nearly ambitious enough — high rises in stone are very much a real possibility.

It’s one thing to design something tectonically in loadbearing stone or wood, but it’s quite another to get the building industry to construct it that way.

When we design something tectonically, we’re forever being undermined by the industry. One builder literally, because he knows us quite well, said, “Amin, my guys will make ten times the amount per person on site doing it in concrete and then cladding it instead of giving it to a stone or CLT subcontractor.” You can go to five contractors, and they’ll all say the same thing, and then they’ll turn around to the client and say, “We’re not gonna do it their way,” and even though we’ve proved to the client that our way is quicker and cheaper, they’ll have no choice but to acquiesce to the construction industry because otherwise their project simply doesn’t get built at all.

Balconies made from wicker-woven steel jut out from the brick façade of Barretts Grove, a six-story apartment building in North London designed by Amin Taha 2014–16. The oversized balconies hang from alternating windows offering residents outdoor space with a measure of privacy while their wicker texture softens the seriality of the double-stacked brickwork. The project exemplifies a playful yet pared down approach to materials evident throughout Taha’s practice.

So how do you overcome that?

Firstly, you design something that can be built within budget and is so irreducible that, if anyone tries to reduce it any more, it’ll fall down. But we couldn’t work out how to avoid falling at the procurement hurdle, until eventually it dawned on us: one, you legally write it into your planning approval, and two, you talk to all the contractors beforehand — the subcontractors, not the main contractor, the brickies, the timber suppliers, the metalworkers, who all come under the umbrella of the main contractor — and get them to quote in advance and hold those quotes for twelve months. Then you collate all that and say to the main contractor, “Right, we’ve spoken to the horse’s mouth, it’s totally doable, so unless you’ve got good reason to do otherwise, here it is. Do it like this and collect your 20 percent overheads, prelims, and profits.” It’s the only way architects can become empowered again — otherwise you’re just a façade designer.

Amin Taha seen watering the roof garden at 15 Clerkenwell Close. Photographed by Harry Mitchell for PIN–UP.

Talking of façades, one of the reasons 15 Clerkenwell Close was attacked was because it doesn’t conform to the usual neo-Georgian default mode of the Clerkenwell Green Conservation Area. But your building is infinitely more authentic than any of the cynical pastiche jobs that have sailed through Islington’s planning process in the past.

If people are to have a voice on aesthetic matters, which is what the democratic planning process is about, then ideally you should educate them at the same time. Whenever we have to do a consultation for exactly that purpose, to try to persuade people, to draw them into the argument, it’s always very interesting. More often than not we find it’s split 50-50, and you can’t point at somebody beforehand and say, “I bet you that person will like it and that person won’t.” We’ve had very young people in super-trendy clothes saying, “Well why can’t it look like the old building next door?” And then you say to them, “Well is the building next door old? It was actually built 20 years ago but made to look older, and if you examine it closely, you’ll see it’s a really bad impersonation of older architecture.” To which they reply, “Oh I didn’t know that, but what does it matter? It looks old and that’s okay.” And you turn to them and say, “Well, if I asked you to dress in a tweed jacket to look like your granddad, but then I got you some cheap-looking plastic printed-Harris-tweed jacket and said, ‘Well it sort of looks the same,’ what would you think?” And suddenly you see their eyes open: “Oooh! I get it!” When you lay it out as a question of philosophy rather than visual looky-likey, most people really appreciate it, and suddenly they’ll be saying, “Yeah, why the hell are all our streets full of pretend nonsense?! Why have councilors allowed this for the past 30 years? Where has the leadership been? It’s an insult to our intelligence!” And you think, “Oh thank god, at last!”

Groupwork designed 168 Upper Street, completed in 2017, as a deliberately distorted replica of a Victorian pavilion destroyed during WWII. A virtual model of the bombed building was used to create a cast from 300 expanded-polystyrene panels. Some architectural details were changed, however, to reinforce the imperfect nature of the memories from which we reconstruct the past. Terracotta-colored concrete was poured into the cast to form the building’s load-bearing shell.

In 2018 Theresa May’s government set up the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission, better known as the Beauty Commission. It was co-chaired by the late philosopher Roger Scruton, a highly controversial right-wing conservative figure who was basically an anti-Modernist and advocate of historicizing Georgian as a suitable style for Britain’s towns and cities. What are your feelings about that?

The whole thing is absurd, because the Conservative government was using it as a way of persuading people: “If we do this, more housing will be built.” And people believed it! They were happy to vote for them again. They sold the idea that not only would the Beauty Commission get more housing built, but that it would be beautiful too. Well it’s just total nonsense. Lack of beauty is not stopping more housing from being built. Instead there are two things going on. One is the NIMBYs, the not-in-my-back-yard crowd, who don’t want any development no matter what it looks like. We’ve done projects in the countryside, and I’ve sat there on the planning committee until ten o’clock in the evening watching 15 different developments being presented to councilors, some of them for 20 houses, some of them for 200 houses, some of them for just one house, and none of them gets refused because they’re unattractive, they all get refused because there’s a bunch of people who’ve arrived shouting, “It’s going to ruin my view!” or “I won’t be able to get out of my drive because of all the cars coming through.” Ultimately it’s because people simply don’t want it, whatever it looks like.

168 Upper Street’s fifth-floor residence showcases the red earthy concrete that dominates the London building’s aesthetic, inside and out. Architect Amin Taha conceived of the design in response to a 2012 competition organized by furniture retailer Aria, whose showroom is on the ground floor. The decision to integrate both external and internal finishes into the building’s superstructure through the use of double-walled insulated concrete saved construction costs.

What’s the other reason?

The second thing is that it’s all a question of the private not the public sector. Ninety-nine percent of housing is built by the private sector, and the private sector is not going to cut its own throat by over-supplying, which means that structurally no one’s going to build the quantity of housing that people actually need. Think about it, we know that developers hold onto land and deliberately don’t build on it to force the value up. And you can’t blame them, it’s in their DNA — their raison d’être is maximum profit. Ever since the late 70s, when an ideological decision was taken to stop building council housing and leave it all to the private sector, the U.K. has become structurally stuck with this system because of the effect on the banking sector. If you lend money on private development — which is pretty much all housing development — you lend up to a certain amount, so a 70-30-percent limit. If you suddenly oversupply and all those values drop, not only does everybody who has a private house suddenly see the value of their property drop, but the bank that’s lent them the money sees their loan book reduced in value. So the whole thing is actually structural. All that’s happening is that certain politicians are holding Roger Scruton up and saying, “This is the man who’s going to solve the housing crisis, because he’s going to show us how to build beautiful houses, and therefore we’ll build more because they won’t be refused at planning.” It’s just a load of nonsense. And then architects getting exercised about whether it’s Georgian or Modern is a total waste of time because these things are not decided on whether it’s Georgian or Modern, they’re decided by NIMBYs and they’re decided by the private sector. And neither of those have anything to do with beauty!

Interview by Andrew Ayers.

Portraits by Harry Mitchell. All other images courtesy Groupwork unless otherwise noted.

Taken from PIN–UP 29, Fall Winter 2020/21.