INTERVIEW: Artist And Writer Aria Dean On Irony, Legacy, and her Interest in Postmodern Architecture

There’s an old Soviet joke, “The future is certain, it’s the past that’s unpredictable.” Writer and artist Aria Dean flourishes in the capriciousness of the past to dissect its re-memory, ruins, and images’ relationship with our material and spatial reality. In her many essays, such as “Poor Meme, Rich Meme” (Real Life, 2016), “Notes on Blacceleration” (e-Flux, 2017), and “Trauma and Virtuality” (Texte zur Kunst, 2018), Dean works out questions related to networked culture and recent histories of circulation, often examining Blackness and its shifting forms. Dean’s visual art — mostly sculpture and video — churns on the conclusions of her writing, with works that are earnest yet jocular, always resisting fixity. This includes her recent forays into theater, in which she uses minimalist scenography to metaphysical effect, like the 2019 Production for a Circle at Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève, where she placed a 360-degree camera center stage. 2021 has proven to be a busy year for L.A.-born Dean, with her work represented in the Made in L.A. biennial and solo shows at REDCAT in Los Angeles and at Greene Naftali in Manhattan. Shortly before her New York opening stylist Becky Akinyode met Dean in her Brooklyn home for PIN–UP to discuss irony, legacy, and frustration at failed jokes.

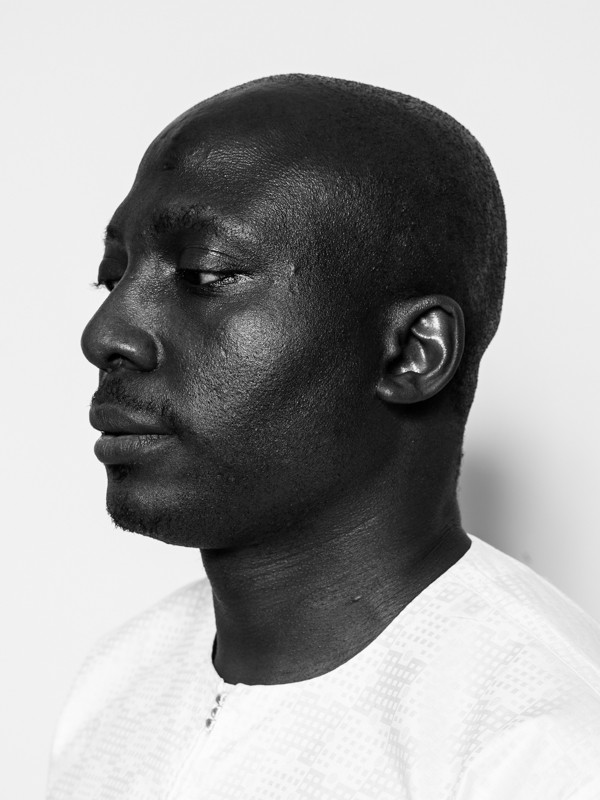

Artist, writer, and curator Aria Dean at her Brooklyn home photographed by Roeg Cohen for PIN–UP.

Artist, writer, and curator Aria Dean at her Brooklyn home photographed by Roeg Cohen for PIN–UP.

Artist, writer, and curator Aria Dean at her Brooklyn home photographed by Roeg Cohen for PIN–UP.

Artist, writer, and curator Aria Dean at her Brooklyn home photographed by Roeg Cohen for PIN–UP.

Becky Akinyode: How do you describe your practice and the work that you do?

Aria Dean: I

Thinking about your writing on memes and your work collaging rap videos, you’re asking if these visuals could represent Blackness, despite not being all-encompassing.

Yes,

The community.

Yes, and

-

Still from Aria Dean, But as one... (rework, feat.) 2019 (2019): Digital video,10 minutes 47 seconds.

-

Still from Aria Dean, But as one... (rework, feat.) 2019 (2019): Digital video,10 minutes 47 seconds.

-

Still from Aria Dean, But as one... (rework, feat.) 2019 (2019): Digital video,10 minutes 47 seconds.

-

Still from Aria Dean, But as one... (rework, feat.) 2019 (2019): Digital video,10 minutes 47 seconds.

-

Still from Aria Dean, But as one... (rework, feat.) 2019 (2019): Digital video,10 minutes 47 seconds.

The last time I saw you was right before you left for Made in L.A. You were telling me about your new play, King of the Loop.

Yes. The narrative revolves around a man who crashes his car in a Mississippi river and finds himself on an abandoned plantation. Three people who are squatting on the plantation take him in. He gets obsessed with this shack on the property, and they tell him a man named Brah Dead lives there. Entering the shack, he finds that the space is a single mirrored room and that Brah Dead is in fact him. He’s forgotten who he is because of the crash and has returned to this location, in a weird metaphysical loop. The writing is all cobbled together, bouncing between novelistic descriptive writing, dialogue, and stage direction. The idea is that we’re taking a period piece and doing it in a void without a set or costumes. Because there is only one actor and cameras are built into the architecture, it became annoyingly more like surveillance-core. I did worry people would ask, “Is it about being watched as a Black person?” That’s some small dimension of that, but it’s not the main idea.

You wanted the architecture to be enclosed and have a surveillance aspect but not to have it be about surveillance.

Yeah, I rarely want anything to be “about” the stuff I’m interested in. Usually I’m just using it all as material. The play I did before this one, Production for a Circle, is about these characters having this insipid dinner-party conversation, and they begin to lose their sense of coherent self, and it turns absurd and nihilistic. I wanted the set to reference fascist architecture, like this strange prison cell in which these actors, all white, undergo this process of dissolving the proper subject — but the play is not about these things, topically.

-

Installation view of Aria Dean, King of the Loop at the Hammer Museum, part of Made In L.A.: 2020, a version, Los Angeles, 2020.

-

Installation view of Aria Dean, King of the Loop at the Hammer Museum, part of Made In L.A.: 2020, a version, Los Angeles, 2020.

-

Installation view of Aria Dean, King of the Loop at the Hammer Museum, part of Made In L.A.: 2020, a version, Los Angeles, 2020.

-

Installation view of Aria Dean, King of the Loop at the Hammer Museum, part of Made In L.A.: 2020, a version, Los Angeles, 2020.

-

Installation view of Aria Dean, King of the Loop at the Hammer Museum, part of Made In L.A.: 2020, a version, Los Angeles, 2020.

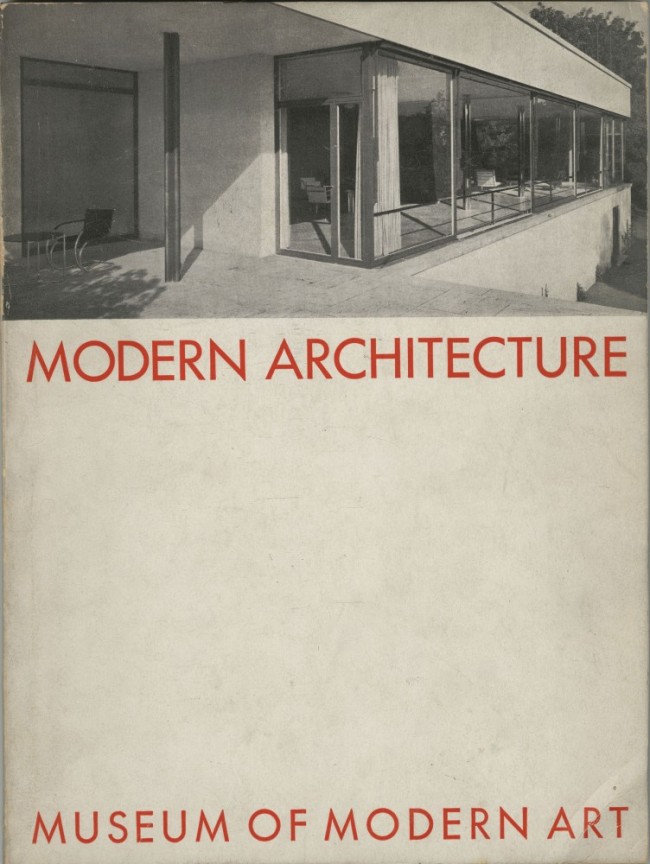

I was thinking about appropriation and how some of your works stem from other existing works. For example, your piece from last year, Ironic Iconic Replica, which is currently shown at the Huntington in L.A., is a copy of a column at Oberlin College that was designed in 1976 by Robert Venturi. Are you purposefully trying to investigate that, or is this out of pure curiosity?

Investigating authorship and appropriation is definitely central to me. For me, it

Yeah. Don’t assume I don’t like white artists.

I became very interested in cross-pollinating ideas that appear to be very far away from each other. I questioned what it meant for me to do that. In part, the Ironic Ionic column was a direct sculptural expression of that. I went to Oberlin, where Robert Venturi designed the art building, so it was this thing I lived with for a long time. It’s a totem for a time when I was consumed with architectural theory, which led me to conceptual and minimal art from the 20th century, work that still consumes me. I’m interested in playing with these references. With the Ad Reinhardt reference, it was often received as a critique of Reinhardt when really I’m quoting him. In critical writing, too, I have this re-combinatory practice. What if I take Nick Land and put him with Frank Wilderson, putting together far-right accelerationism and Black radical theory with ties to a far-left position? What if there’s a resonance between the two?

Did it have to do with the legacy of this object?

I was interested in the legacy of it, and that of Postmodern architecture at the time. But the other reason I did Ironic Ionic Replica was because Greene Naftali (where it was first shown) has these white columns. Robert Venturi’s original column in Oberlin is in natural wood. What happens if you take an object and make a slight change to it in a different space? How does it fit in relation to the original? Is it a copy or is it new and different? Which is also a larger question that art has always asked. It was interesting, because in its new material the column masked itself in the space among the other columns, so people would ask, “Where’s your piece?”

Installation view of Aria Dean, Ironic Ionic Replica at Greene Naftali, New York City, 2020.

Because there were already columns in the space next to it, your piece became part of the existing architecture.

Exactly. And of course, the original was called Ironic Ionic. I’m really interested in irony and, here in the way Postmodern architecture ironizes history. I’ve made a lot of sculptures that attempt to be ironic, too, but in my experience it’s very difficult to be a Black woman and be received as ironic.

I’m thinking of your works like the bow tied to the chain, or the cotton branch in the glass case.

Exactly.

It’s this idea that we can’t be funny.

Cotton is so self-seriously employed

Yeah, that’s part of being Black.

For some reason, if I make an object that makes a joke,

-

Aria Dean, Mise en abyme 2.3 (2020): Blackened steel with stainless steel standoffs, 35 x 30 inches.

-

Aria Dean, Mise en abyme 1.0, 2020: Blackened steel with stainless steel standoffs, 43 x 36.25 x 2 inches.

How does legacy play out in your work?

To me legacy means a holdover, a chemtrail, or an afterglow. My work overall is pretty preoccupied with that in terms of these material and cultural histories. Like with race, there is an intensive legacy to be drawn upon and made use of in an effective way. If we are operating within a framework

Exactly.

I get interested in the question of time and the desire to draw things into a solid sense of linear history, but also the desire to approach a given contemporary moment as an enclosed present. There is a tension right now between an obsession with the historical, with legacies, and a totalizing ahistoricism. Which opens onto a tension regarding responsibility. We all have to consistently grapple with the long tail of history, while also trying to get out from under it and make a livable life for ourselves.

I think that’s what it means to be a Black person living in a white-supremacist world. You have to accept the good and the bad of that legacy.

There are ways in which I am so aware of my existence in the shadow of slavery and anti-Blackness and how my existence is colored by them. But I am also aware of the fact that I grew up with relative privilege. I try to make work that feels genuine in the way that I am engaging with it, such that I’m not taking on a greater relationship to issues than I actually have. I don't wake up in the morning saying, “Another Black day as Aria Dean.” How much am I subject to history and the legacy of these things? In a way I would like to not have these things on my shoulder, but they are also part of what makes my thinking and work possible in the first place.

-

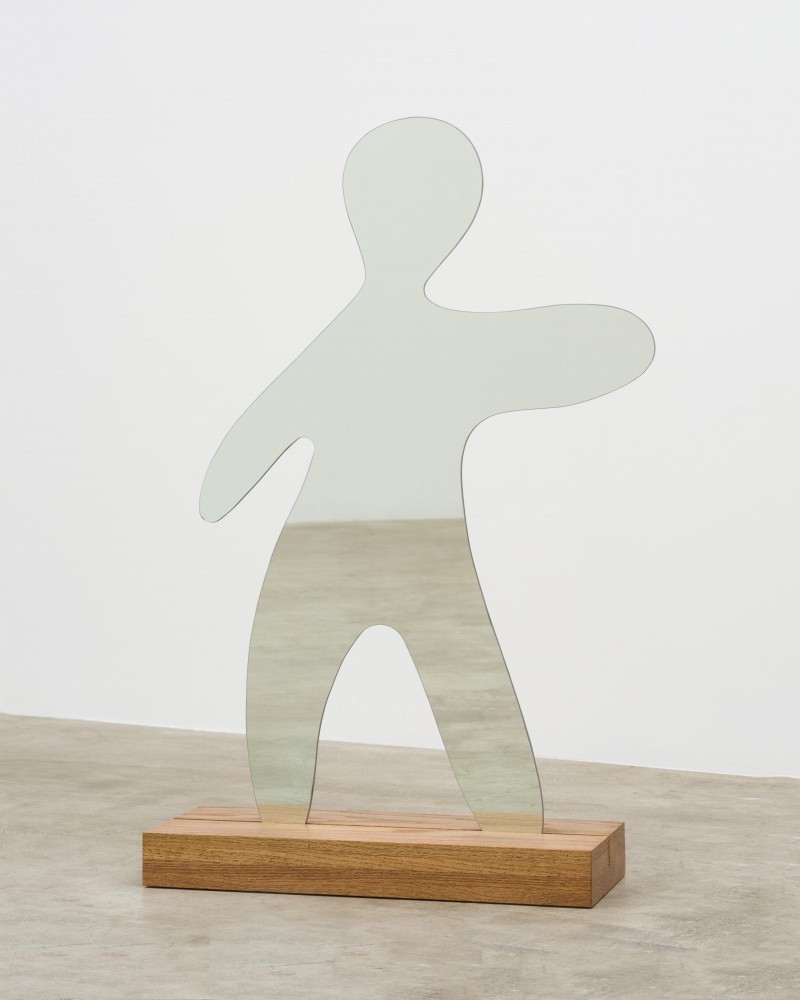

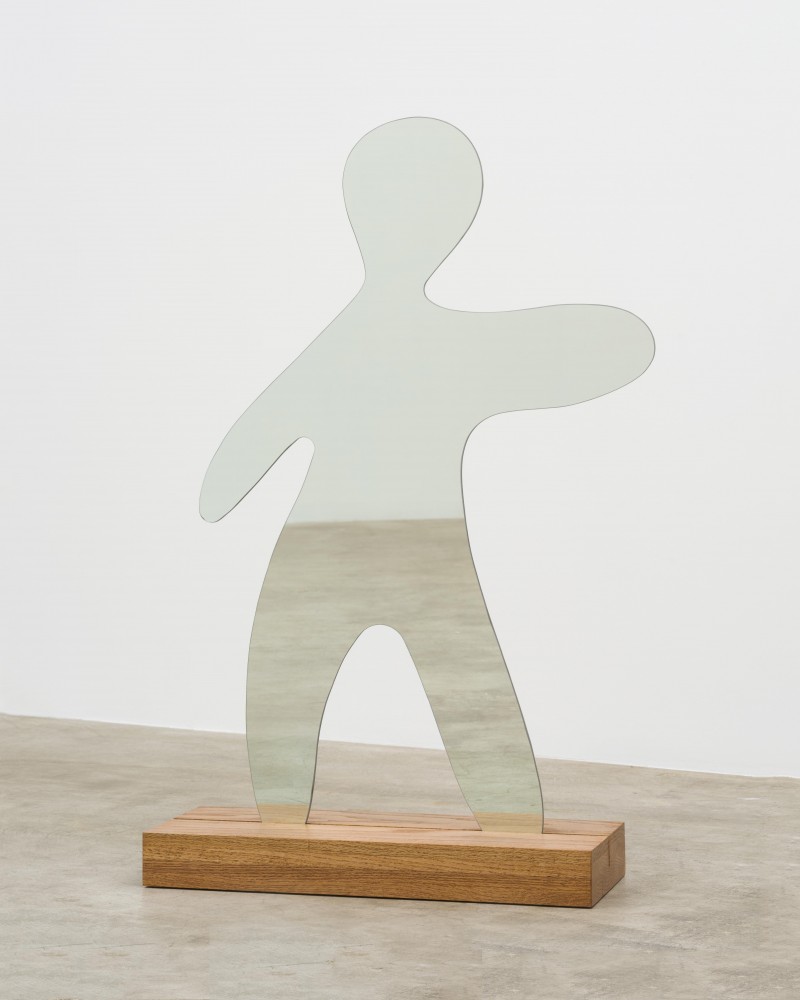

Recto view of Aria Dean, metamodel: in (2019): Security mirror and oak, 38.0 x 26.0 x 10.0.

-

Verso view of Aria Dean,metamodel: in (2019): Security mirror and oak, 38.0 x 26.0 x 10.0.

-

Verso view of Aria Dean, TBC (meta)model (2020): Security mirror and wood, 48.5 x 28.5 inches.

-

Recto view of Aria Dean, TBC (meta)model (2020): Security mirror and wood, 48.5 x 28.5 inches.

-

Aria Dean, (meta)models: fam, stand-in (2019): Security mirror and birch, 40.5 × 20 × 20 inches.

Accepting the legacy but not being bogged down by it.

Yes. And truly making something of it rather than getting caught in the whirlpool. For white people it’s a similar negotiation, for them it’s like how much responsibility do I have for this legacy. Last summer was crazy in that sense.

Yeah, it was like, guys I’ve been known these things. I was reading more of your writing in respect to Blaccelerationism, and there’s this idea between the right and the left about a new society, the right is like capitalism will progress until destruction is reached, and the left is like yes, but there will be a new entity that will emerge and exist in the new world. Originally Black people were treated as commodities, they weren’t thought of as humans so they could be the entity that then inherits the world at the end.

I think

-

Installation view of Aria Dean, Show Your Work Little Temple at Greene Naftali, New York City, 2021.

-

Installation view of Aria Dean, Show Your Work Little Temple at Greene Naftali, New York City, 2021.

-

Installation view of Aria Dean, Show Your Work Little Temple at Greene Naftali, New York City, 2021.

-

Installation view of Aria Dean, Show Your Work Little Temple at Greene Naftali, New York City, 2021.

Wait, so you have new shows coming up?

I have a show at Greene Naftali on May 7th, then I have a show at REDCAT in Los Angeles, which is a video installation. The Greene Naftali show is sort of two related bodies of work: sculptures that are 3-D printed digital assemblages made of actual and virtual objects, coated in a very glossy black silicone rubber. The pedestals which the work sits on look like sections of the Venturi column. Then the other works are engravings based on drawings I have done mixed with online imagery turned into line work, similar to Les Simulachres at the Hammer. They are gum sole rubber material this strange almost fleshy material.

I feel like there is a bit of trickery in your work.

Definitely, trickery is something I am interested in, it is a sort of bait and switch slash, a kind of like psych.

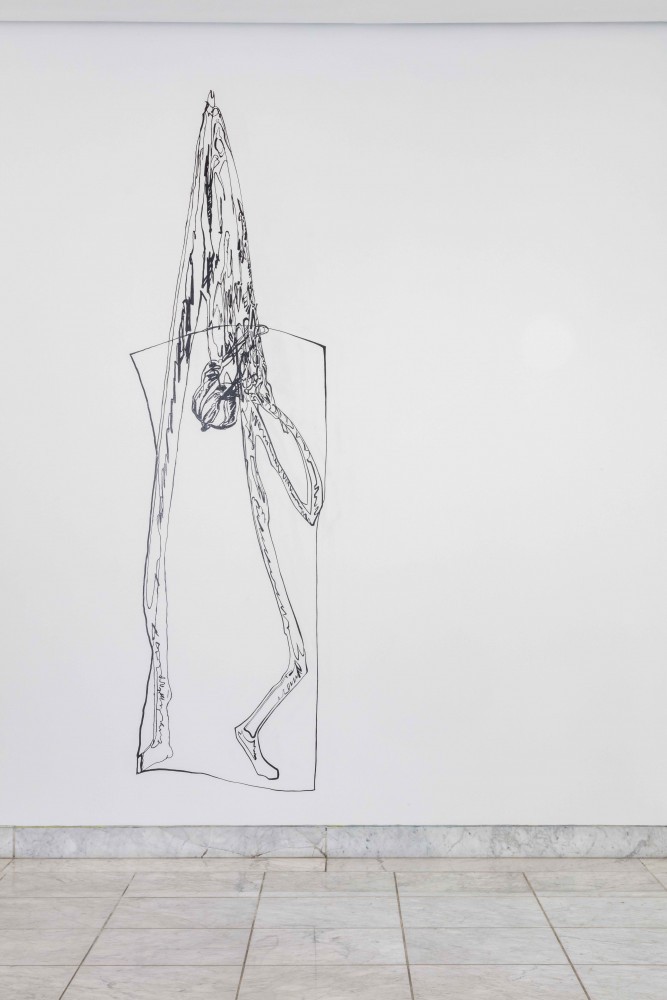

-

Aria Dean, Les Simulachres, 2020. Installation view of the Hammer Museum’s Wilshire Lobby wall. Photography by Joshua White.

-

Aria Dean, Les Simulachres, 2020. Installation view of the Hammer Museum’s Wilshire Lobby wall. Photography by Joshua White.

Okay, last question, I was reading about your show Studio Parasite (at Cordova in Barcelona), and the idea of the imaginary threat struck me. Kudzu is an invasive plant, but it only grows in direct sunlight, so it can’t overtake forests.

I went back to Atlanta to see my maternal grandmother in summer 2019, and she pointed out the kudzu — something she’d always do when my brother and I were visiting. After that visit I was doing some research on the plant, and I came across a debate about kudzu and whether it’s actually as invasive as people have said. It actually has a lot of trouble growing in the darker parts of the forest; so its presence is nearly purely aesthetic. The gap between actuality and the cultural imaginary has always interested me, especially in relation to Blackness. The kudzu is a great proxy object through which to consider this.

-

Installation view of Aria Dean, Studio Parasite at Cordova, Barcelona 2021.

-

Detail view of Aria Dean, Studio Parasite at Cordova, Barcelona, 2021.

-

Installation view of Aria Dean, Studio Parasite at Cordova, Barcelona, 2021.

-

Installation view of Aria Dean, Studio Parasite at Cordova, Barcelona, 2021.

Assumptions that are not based in reality are a very American thing to have.

The parasitic thing felt parallel to my understanding of Blackness. The kudzu appears to be parasitic, like Blackness, which is a thing that grows over things but gives it a shape and also a sheen.

Blackness always affects the thing it’s in relation to.

It envelops, and it is viral. Kudzu is a great object to work this out through.

Is it trying to find the core of Blackness?

It is saying that Blackness is a material. To me, that is how I relate to Blackness in my work and writing. As a material inherently present in everything I do.

Interview by Becky Akinyode.

Concept and introduction by Marco Estrella.

Portraits by Roeg Cohen.

All work images courtesy the artist; Greene Naftali, New York; and Château Shatto, Los Angeles.