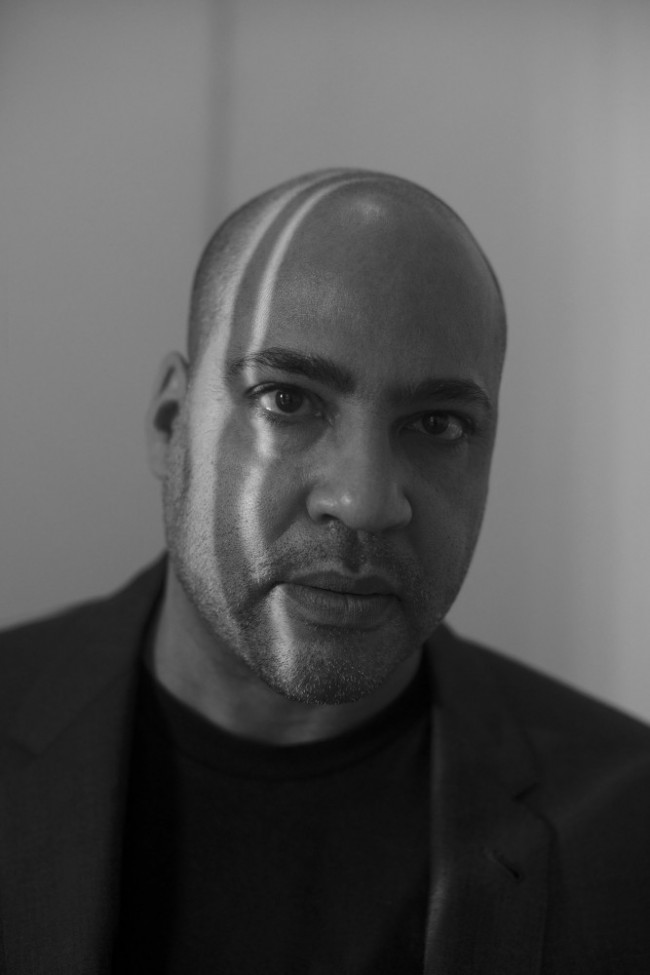

INTERVIEW: Artist Kandis Williams Is Giving History A Hard Read

Artist Kandis Williams is a reader — a deep reader. She is a depth charge dropped into the dark unconscious of texts, images, films, and the sundry corners of social media. She detonates in places where Blackness — our art, music, skin, hair, bones, asses — become raw material for the projective fantasies that are at the center of what we blithely refer to as the history of Western thought. And for over 15 years she has told all of us, in collages and texts, performances and publications, and through her imprint Cassandra Press, that something malevolent has been quietly rehearsing its entrance from the wings and now has taken center stage. “What would the world look like if Black women were believed?” Kandis asked us midway through our series of conversations while the country around us conflagrated. She asked how it was possible that Black women — whose labor is “the belly of the world,” who have borne witness to it all from the inside out — have never been believed? It remains one of the great, unresolved crimes that the very women who provide the affective fuel that feeds art and literature, slang and gesture, meme and tweet, plump and implant, white backshot and squat rack, song and dance, the very women who have weathered the brutalities of the American experience as poets, prophets, philosophers, historians, and witnesses — that they have never been believed. In a year when Kandis will feature in the Los Angeles biennial, Made in L.A. 2020: a version at the Hammer Museum, and has a retrospective opening at the Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University titled Kandis Williams: A Field, we sat down and took a long view of her practice, back through all the years where she had been (been) doing the work, long before this quote-unquote moment.

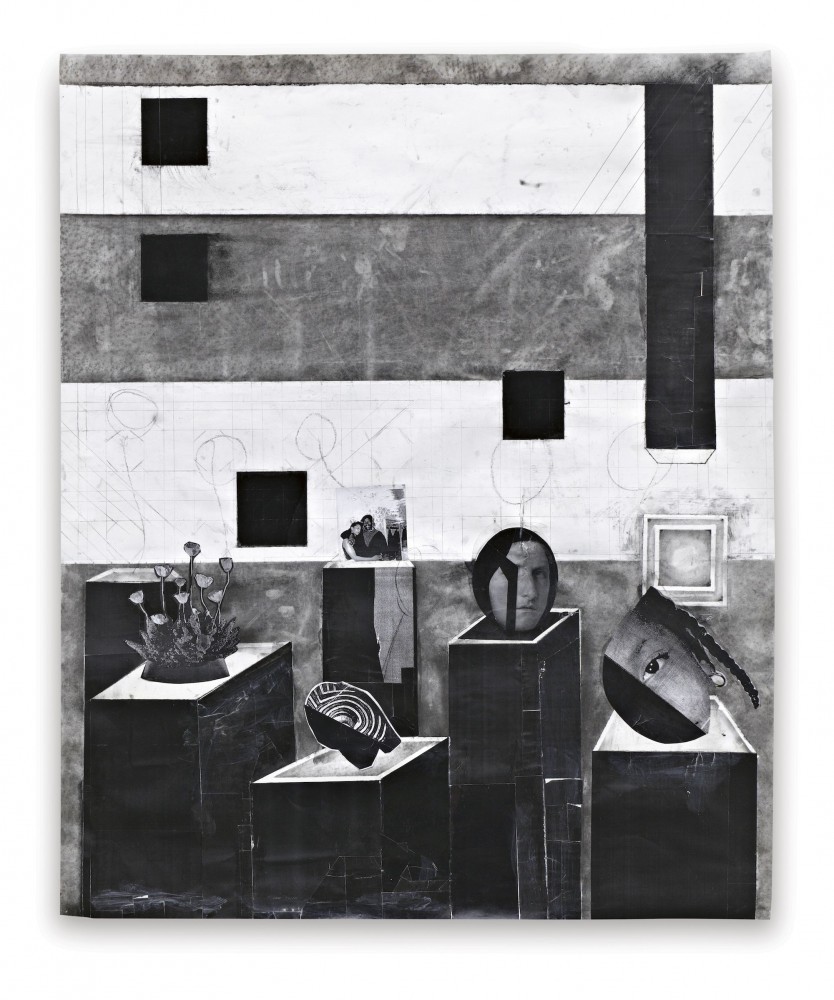

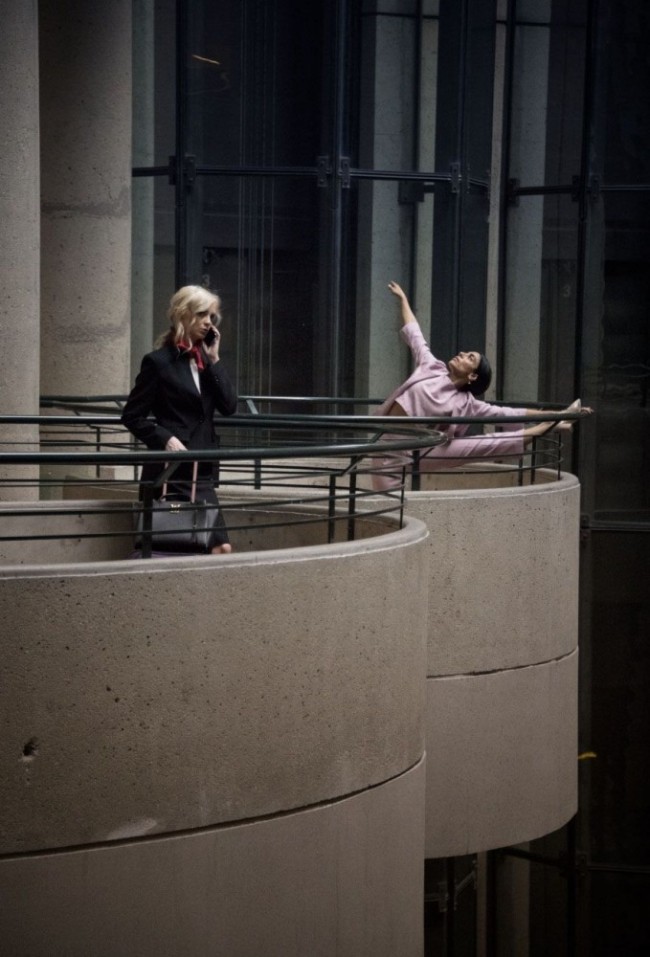

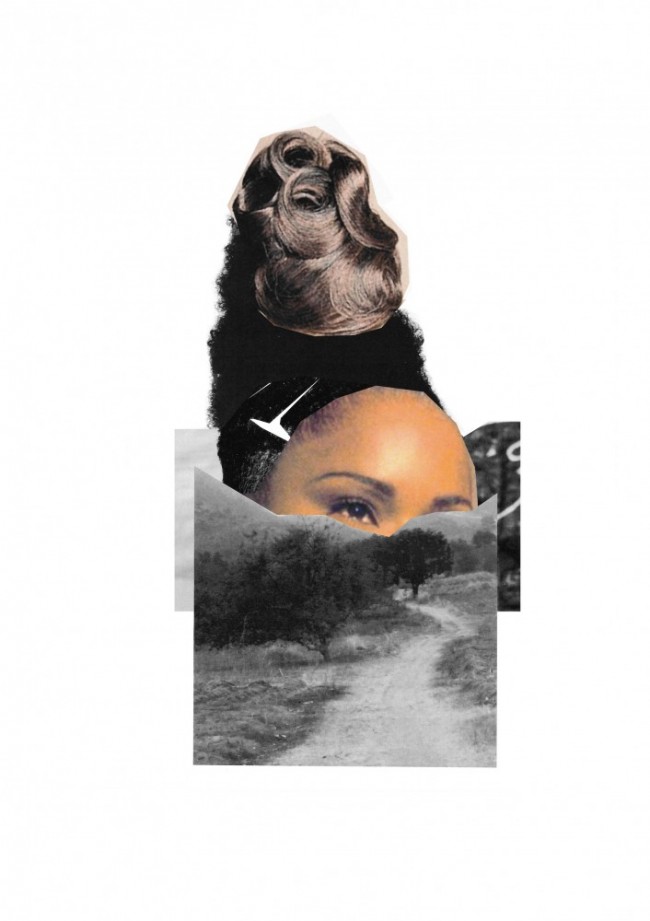

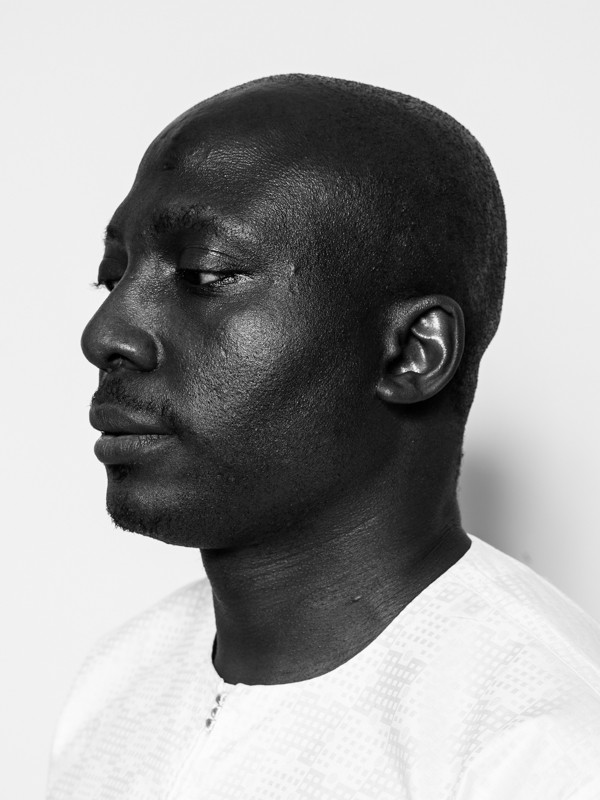

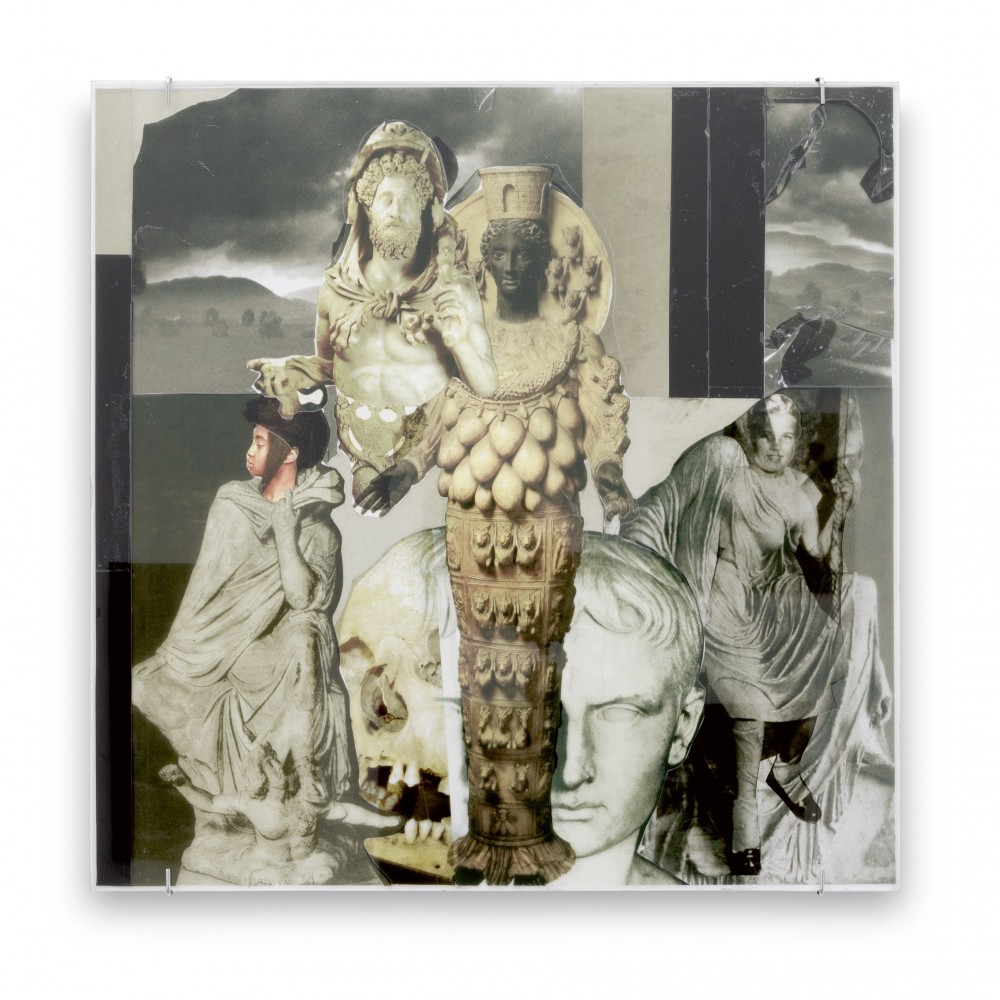

Kandis Williams, Pedestal (2013); Collage print on paper: 48 by 36 inches. Courtesy the artist and Night Gallery.

Chloe Wayne and Mahfuz Sultan: Let’s start with where you’re from, Baltimore.

Kandis Williams: My memories of high school are walking around the city and the rural suburb of Randallstown — the “red light” district downtown on Baltimore Street, the open fields and then suddenly urban streets around the Baltimore Museum of Art — at night all surrounded by these incandescent lights. When the Ravens won the Super Bowl in 2001, they lit all the downtown buildings purple in the city that year. It gave it this weird purple Gotham look. There is a wooded bend right before you turn onto my grandma’s street that felt as big as a whole forest… Playing in creeks behind big Section 8 apartment complexes in the county and then driving back through the orange-lit highways to go home to the city.

Was that Bruce Nauman neon Violins Violence Silence up on the façade of the Baltimore Museum of Art at that time? Did the building have any significance for you?

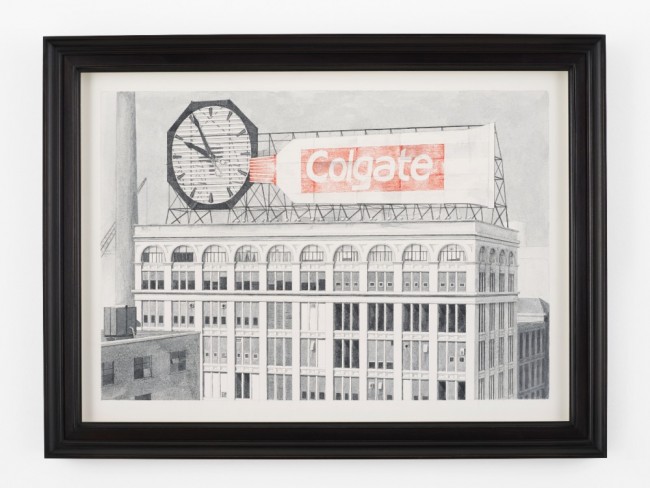

Yeah it was. The BMA is one of those weird bubbles where it’s actually in a Black neighborhood that abuts a poor white neighborhood except for three streets that cul-de-sac around the back of the museum, where there’s Johns Hopkins University and the Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum. I think buildings in general had significance for me growing up. Interiors and domestic spaces without doors, half-finished cement steps, those worn-out stoops that are very Baltimore — limestone, and floral weldings. A lot of decay. I feel like I end up in cities that have that quality. Berlin certainly does. New Orleans, Mexico City, St. Louis, now working raggedy-ass Los Angeles.

How did you end up at Cooper Union?

There are two art high schools in Baltimore, one in the city and one in the county. We could go to county schools, so I went to that one, Carver. A couple kids from Carver would get into Cooper every year — there would be this sort of intra-school competition to see who would be the best art kid who’d get to go. I remember when I got in. A friend of mine came over to open the letter with me, and we cried. Nobody really went to college in my family, me and a few cousins really started that wave in our family. There was still never a sense for how I would pay for college, so I always had a thought that if there’s a free art school that’s the best, I would go there. It was literally the only option.

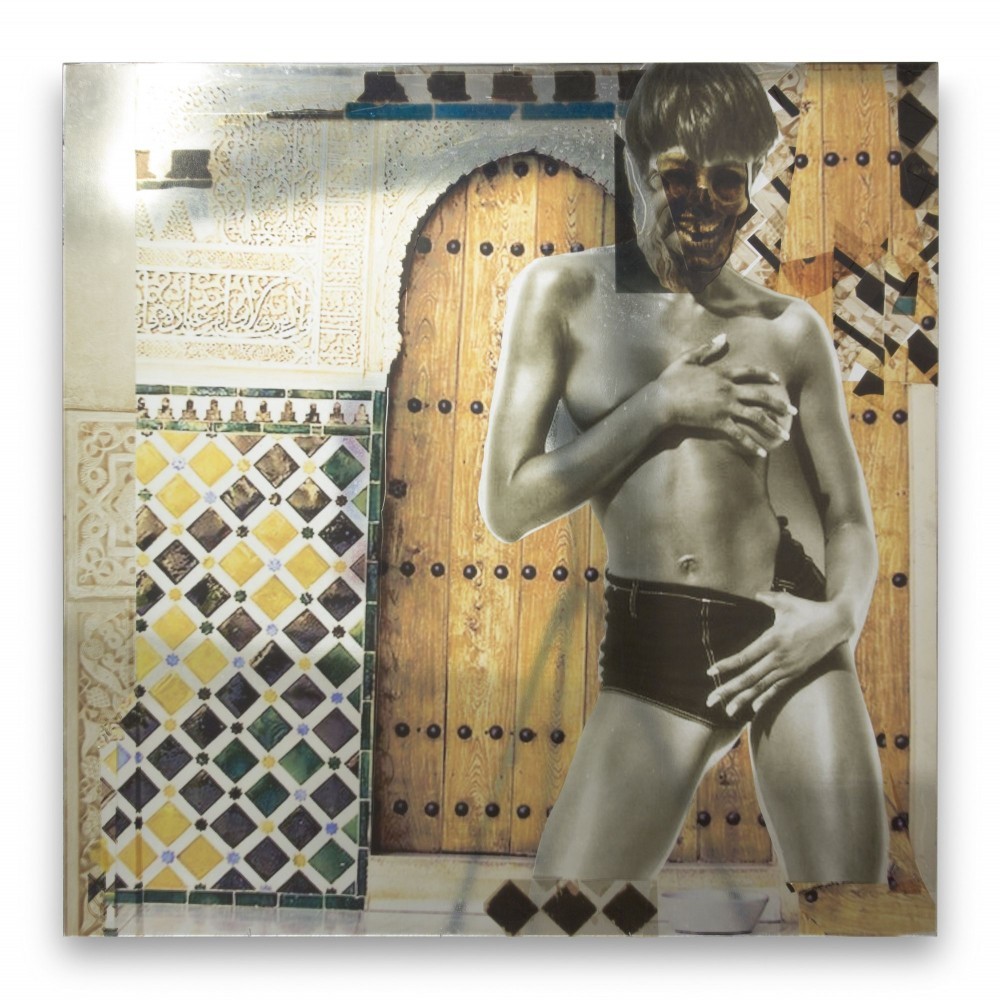

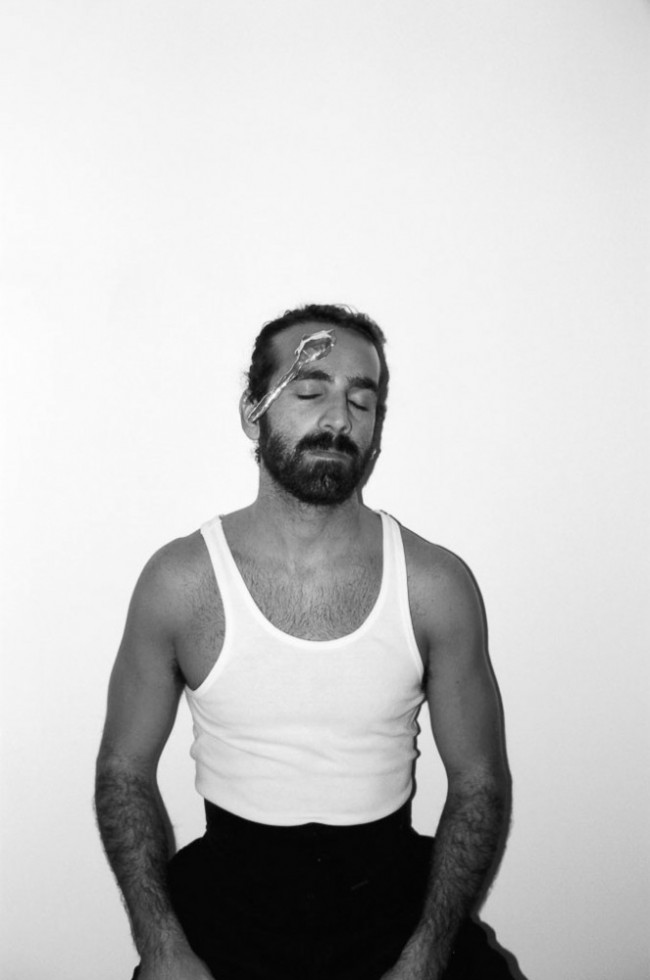

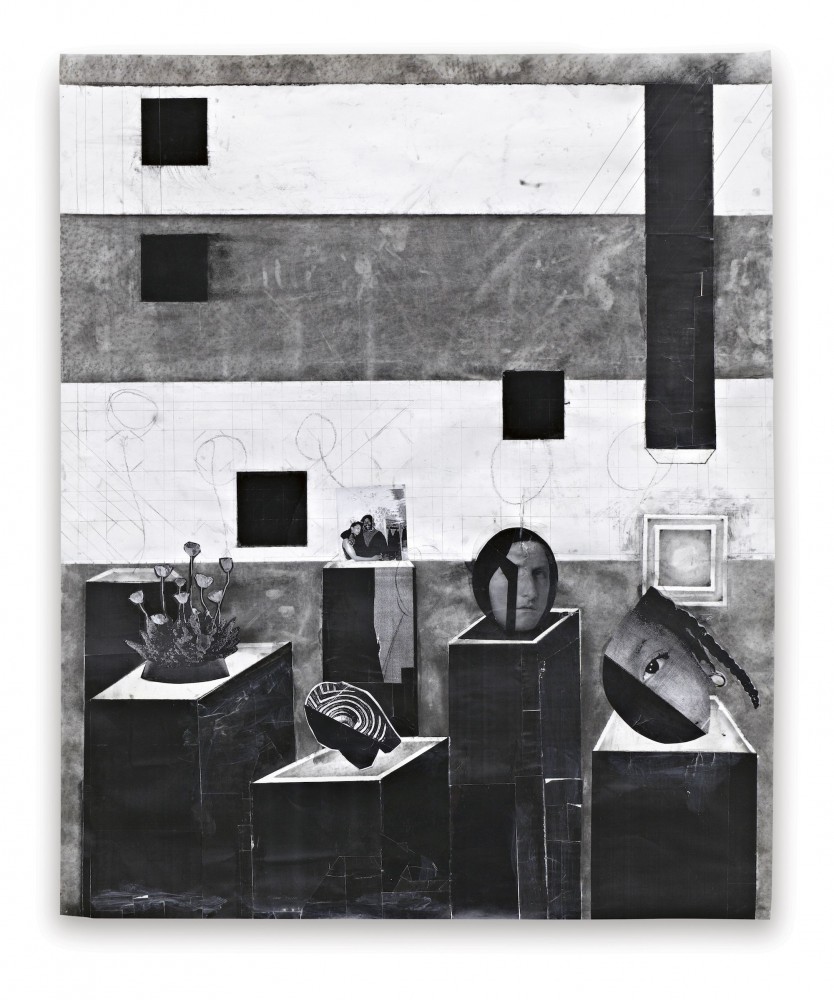

Kandis Williams, Acheron Death Mask II (2018); Vinyl adhesive on mirror; 48 x 48 inches. Courtesy the artist and Night Gallery.

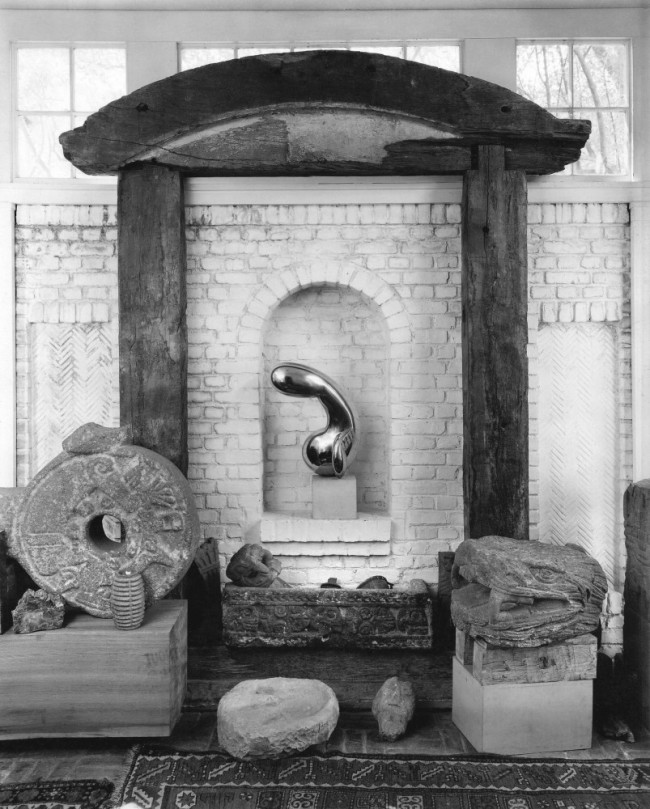

When did you start engaging with architecture?

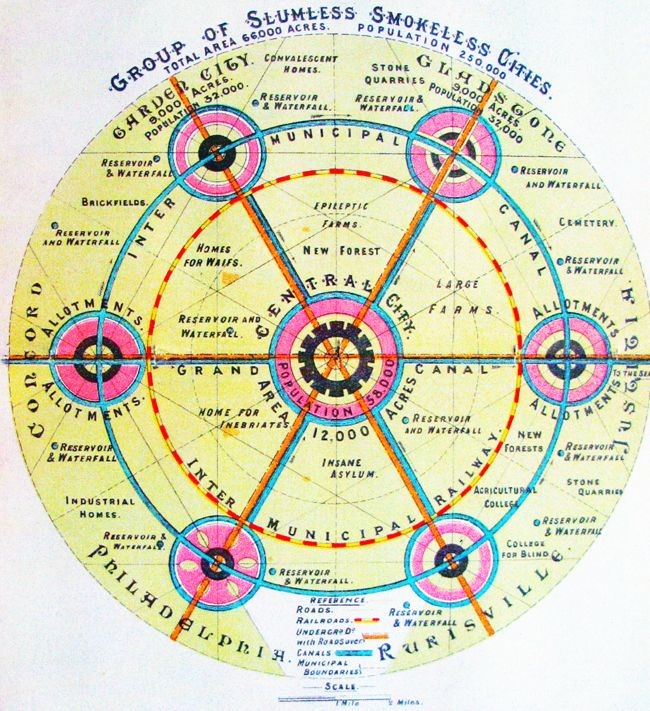

Definitely at Cooper. I actually still have my textbook, Programs and Manifestoes on 20th-Century Architecture. I was really into Bruno Taut, and Adolf Loos’s Ornament and Crime. I got way too into Le Corbusier’s biography and all of his scandals. Living in New York, the Situationists and dérive, then Rem Koolhaas’s means of collaging urban space into book form, were all really impactful.

Were you making art at the time or mainly just reading?

My time at Cooper was fucked up because I wasn’t making anything clearly. I think learning about conceptual art really paralyzed me. I did art as a kid in the hood, so my practice was completely different. There’s a sort of artisanship in Black space — you’re congratulated for being able to draw, for being able to paint, but it’s no one’s whole career. Art-making is like a thing everyone does on some level maybe, especially in Baltimore, a tangle of kitsch and poverty. There was no stiff conceptual apparatus to what I was learning in high-school art classes. So getting to Cooper and learning about this completely different world of conceptual art and white people who couldn’t paint water lilies was really difficult in ways I still struggle to understand. I stopped making stuff basically. The last three paintings I made at Cooper were these collage portraits of white Western guilt set onto architectural schematics. Cain, Oedipus, and Lady Macbeth collaged onto African figures and images of African genocides and production stills from English theater renditions. The self-portrait of Artemisia Gentileschi set atop the architectural plan of the Pentagon. Other than that, I was just doing acid and thinking about stuff. I had a wall in my studio that was always full of patterns. Locating patterns from around the world, where they came from and how they migrated into other patterns — different textures, weavings, pottery. I think that came out of Loos and being obsessed with Ornament and Crime and coloniality. Cooper was also a nest for making bad sculpture, fuck-sculpture sculpture — I’ve dabbled in that to this day. I was reading a ton, just reading insane amounts. I was in the art school, but dabbled and crossfaded in architecture courses for a year before a big breakdown. It was a Cooper rite of passage to design a hut, a prison, or a church — Brunelleschi’s architect-is-everyman type shit — which struck me as really megalomaniacal. I got this book (Programs and Manifestoes on 20th-Century Architecture) and I was like, “Fuck everybody!”, and I just took this book and highlighted all the exclamation points from every manifesto, and that’s what I turned in as I moved through those courses. Shout out to Rod Knox for being the best architecture teacher to observe in motion.

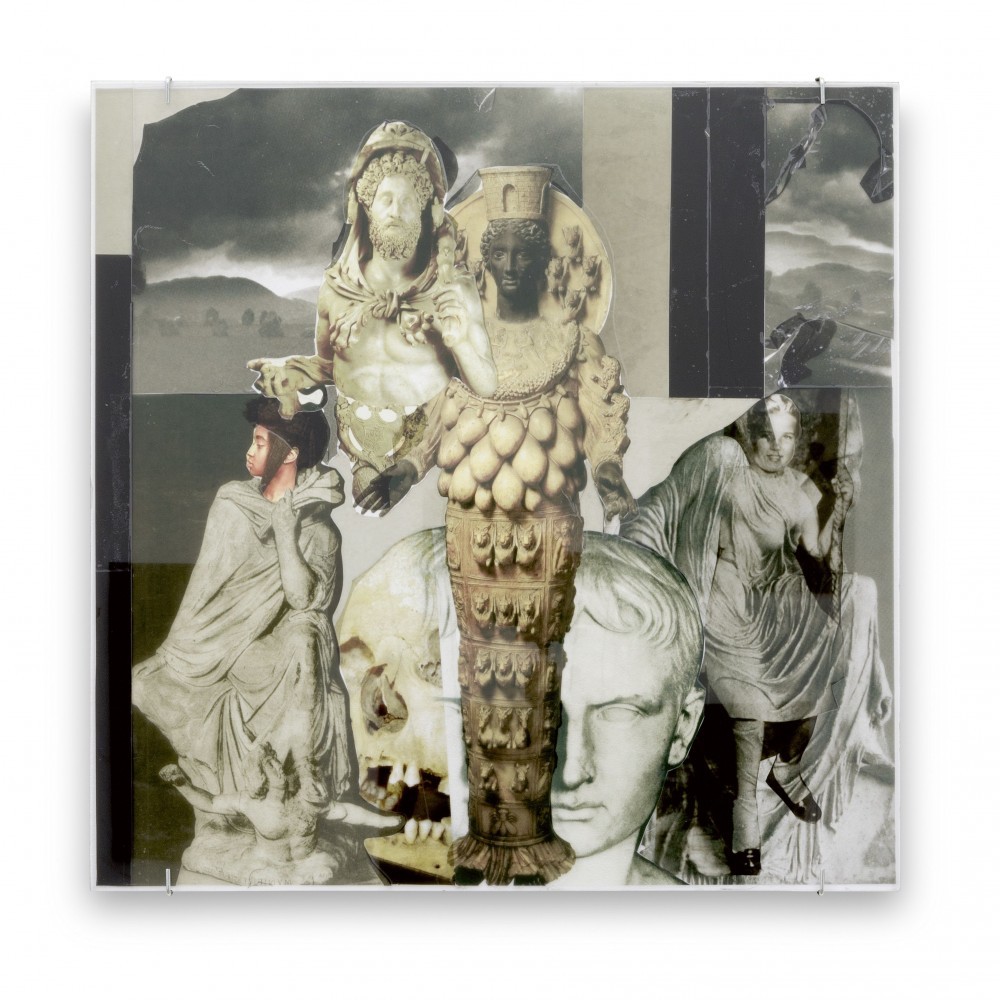

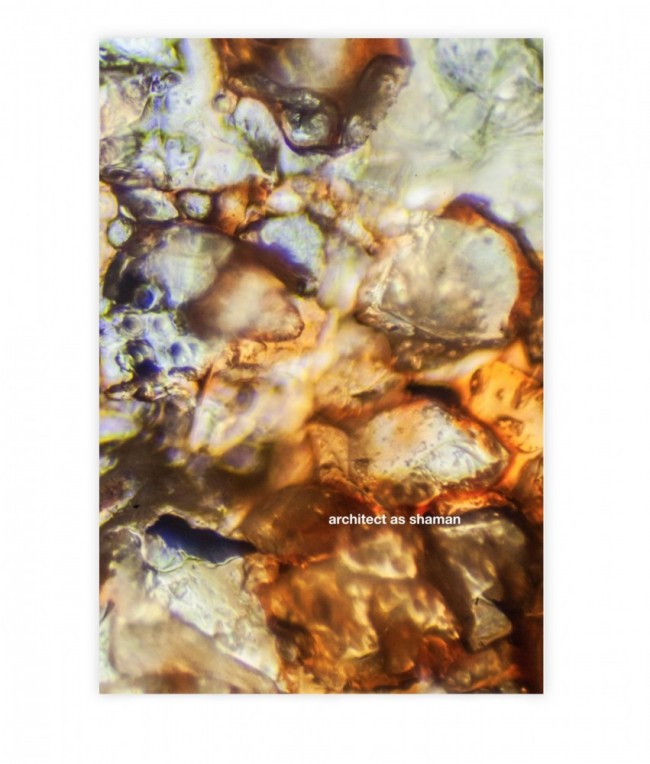

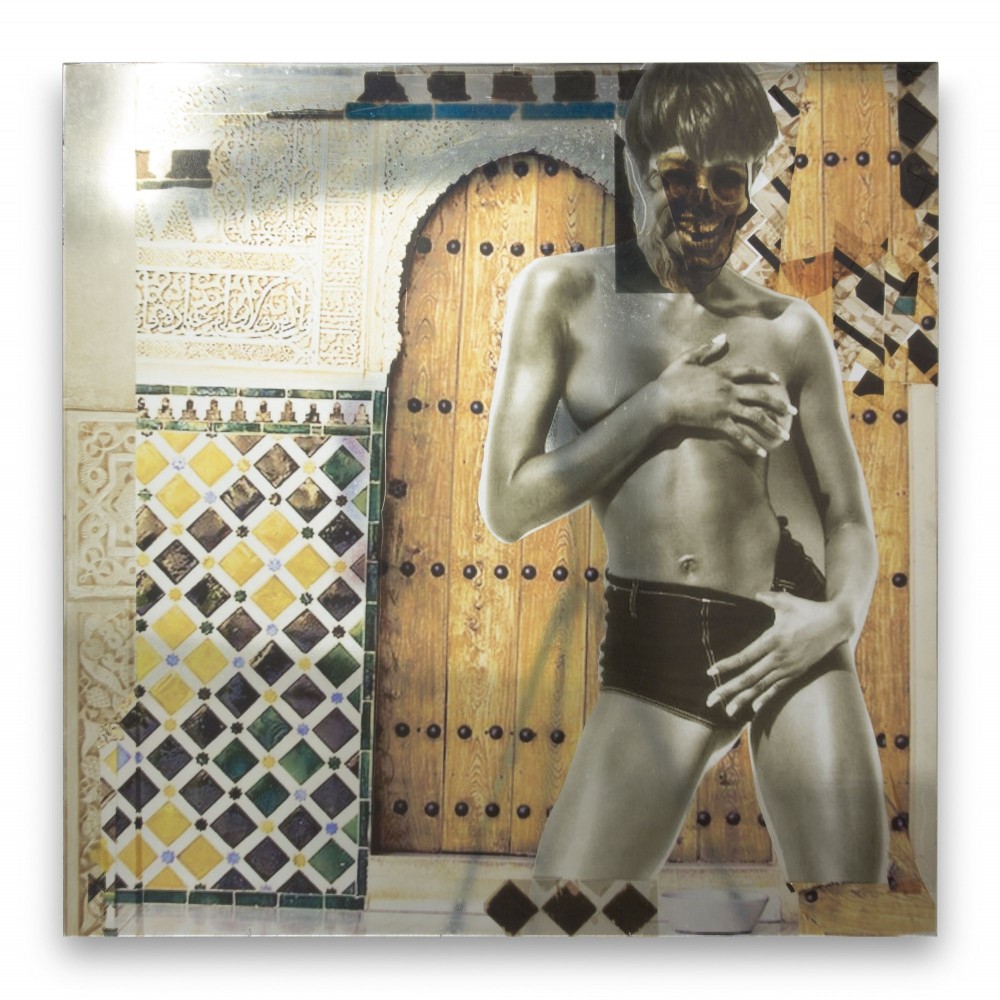

Kandis Williams, Styxx (2018): paper, collage, plexiglass, and hardware 7.75 x 6.5 inches. Courtesy the artist and Night Gallery.

When I think about your work, I think of your engagement with popular culture on the one hand and then literature, philosophy, and scholarly writing on the other. These parallel tracks of reading and research converge at certain quilting points, and you generate a body of work from those. When was the first time you felt you were starting to produce work, like “work work,” based on what you were reading?

I still don’t feel like I’m making “work work.” It was actually the inverse for me. I was in the art world from the beginning, being at Cooper. But even then, I was never convinced of the art world as a thing to do. I started directing arts-based nonprofits, teaching art classes for kids, and giving the homies teaching jobs right after school. It felt redemptive in a way. What is nice lately is feeling the traction of things repeating in my own mind. Feeling a strong foundation for a lot of my ideas to take different forms — a play, a book, a website, a piece of writing. It’s feeling more and more like I’m producing from that well. The more that becomes a well, the more I feel like I’ve made stuff and that I’ve always been making stuff in this way.

It’s almost as if you’re a logic and you can operate on anything. It’s interesting to see your influence on artists working now, and to see you take on the role of an elder of sorts.

I don’t have a sense of my position in that way. Trying to protect my practice has been a big part of things. But I struggle with recognition because the work is all form developed in concert with other people. I can be self-deprecating. Sometimes I’m like, “Oh, it’s just something in the Geist,” or that “it’s just the moment we’re in.” Other times, I sit and think about it, and I’m like, “But wait, I really did specifically do something here.” (Laughs.) I would be interested to know what you think. What is my work?

I think there is something fundamentally linguistic at play in your work, and you use things like binary transposition in very precise ways. And if a viewer gets what you’re transposing, there’s this detonation.

It’s like the bomb doesn’t detonate a lot right? That was the struggle. Like looking at patterns on LSD — for a long time I considered my only practice to be liquidating photographic content, reducing a picture to the blur, how (Josef) Albers talks about light and color, how to demolish the architectonics of a photo. I was looking at a lot of (Dziga) Vertov. The early works were these wall-sized tableaux, collages. They were attempts to deal with different sorts of trauma by connecting the elements of photographs and making architecture out of those experiences, ways to schematize feeling as a sort of traumatic response.

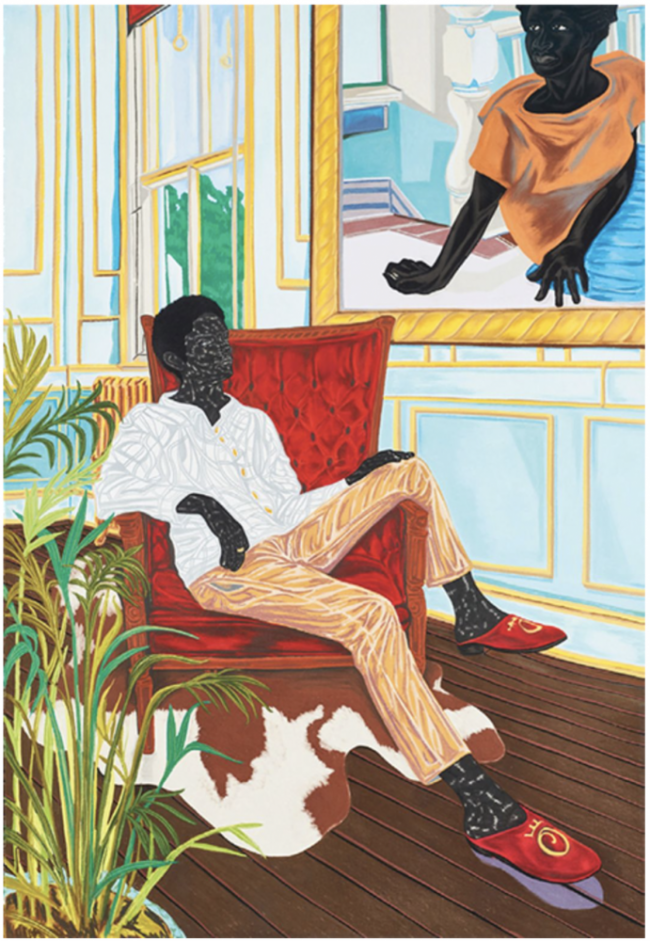

Kandis Williams, Velvet Square (2013); Collage, print on paper; 56.3 x 56.3 inches. Courtesy the artist and Night Gallery.

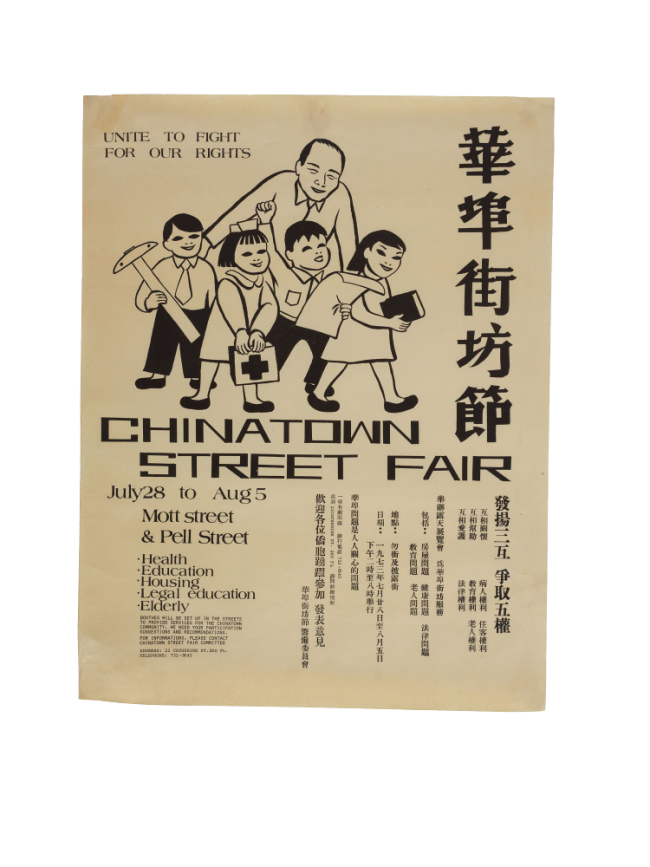

Your interest in collage, Dziga Vertov, and montage all feels related to the Cassandra Press readers you produce. When did you start to feel like the readers would have value for your art practice?

I made my first reader in high school. A midnight group of us would meet up and make flyers. Or we’d put together a bunch of shit that we weren’t learning at school, alternative histories. I was making a lot of punk flyers, and I would bind them or turn them into flip books. My little sister got really into music at some point — I had a banjo and a drum set, and she decided she wanted to play the keyboard. So I got her a keyboard and made her a book of Black women pianists, like Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou, and included a bunch of sheet music so she could start to learn. That was my first reader. And from there, I would just do shit like that. But it wasn’t art-based. I would do it as a part of the communities I was in. Print stuff out, scan it, put it together — clip-bound or with three-ring binders. When I moved to Berlin, I started doing dramaturgy, making readers for other people. I’d apply for grants. I received a grant to do dance documentation, so I started making readers on dance and doing dance-film screenings, talking to dancers a lot. That’s how I was able to maintain access to a lot of archives throughout Europe while I was living there. So I kept doing that for a while as it was funded and a fresh curiosity, while also continuing to make collages and works on paper. I still have two very large suitcases full of Xeroxes that I’ve carried around for almost 15 years.

When I started getting into making books, there was something about how quickly one can finish something using a Xerox machine. That’s always been immensely satisfying for me. The distance between the idea and the finished version of the thing being so incredibly close.

It’s insane! You just fold a page, hand it to someone, and they read it!

They are also graphic artifacts. Reading the titles and names of the writers side by side. The relationship between the cover image and the content. They are sort of works on paper, pulled down off a wall, and then sequenced and distributed.

One-hundred percent. The sequencing becomes a sort of concrete poetry.

With everything that’s transpired in 2020, it feels like a broader audience has recently found Cassandra Press as an educational tool to navigate the “moment.” Your readers are often sold out. Everyone is finally listening to Cassandra, so to speak. How do you feel about that?

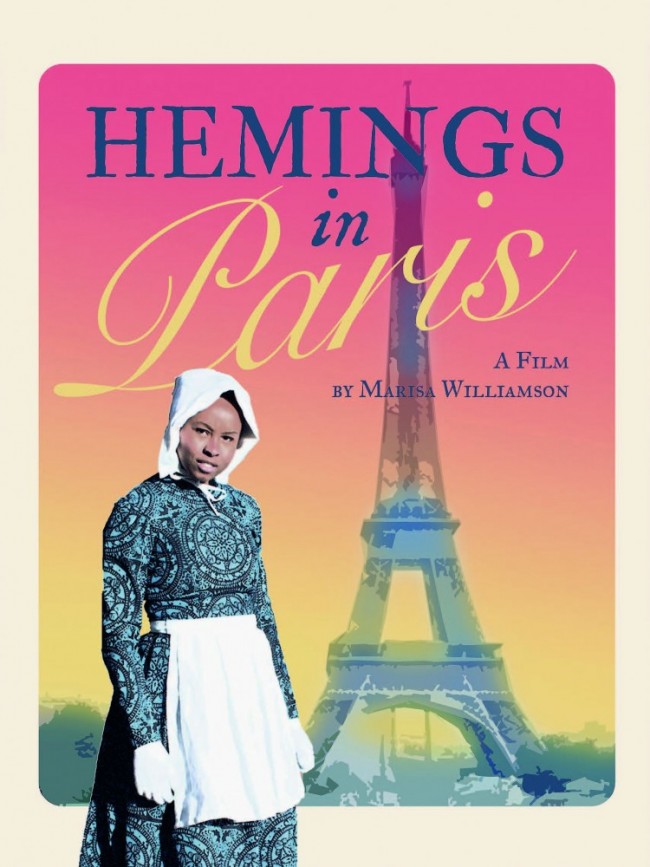

It’s so funny isn’t it? What charged the myth of Cassandra for me was a link I saw between her as a disregarded prophetess and the role that radical Black femme scholarship has played for so long as hyper-signalled and yet perpetually unheard and disregarded. It’s this state of embodied marginality. Black women are at the center of so many systems of labor. We’re denied hermeneutic and epistemic validation, but then tapped for so much entertainment, sexuality, affective registering, and orientation. And so the figure of Cassandra has always resonated with me. Cassandra Press is a site for my historical fantasies. What would abolition look like if Anna Murray Douglass was where she should be? What would concert music sound like if Nina Simone were positioned where she should be? What would the world look like if Black women were believed?

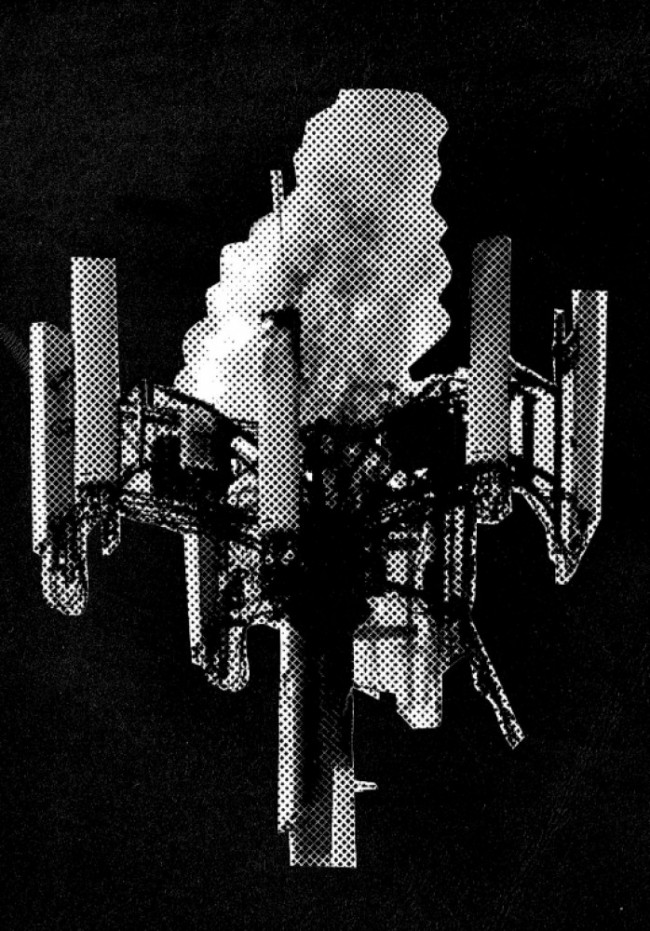

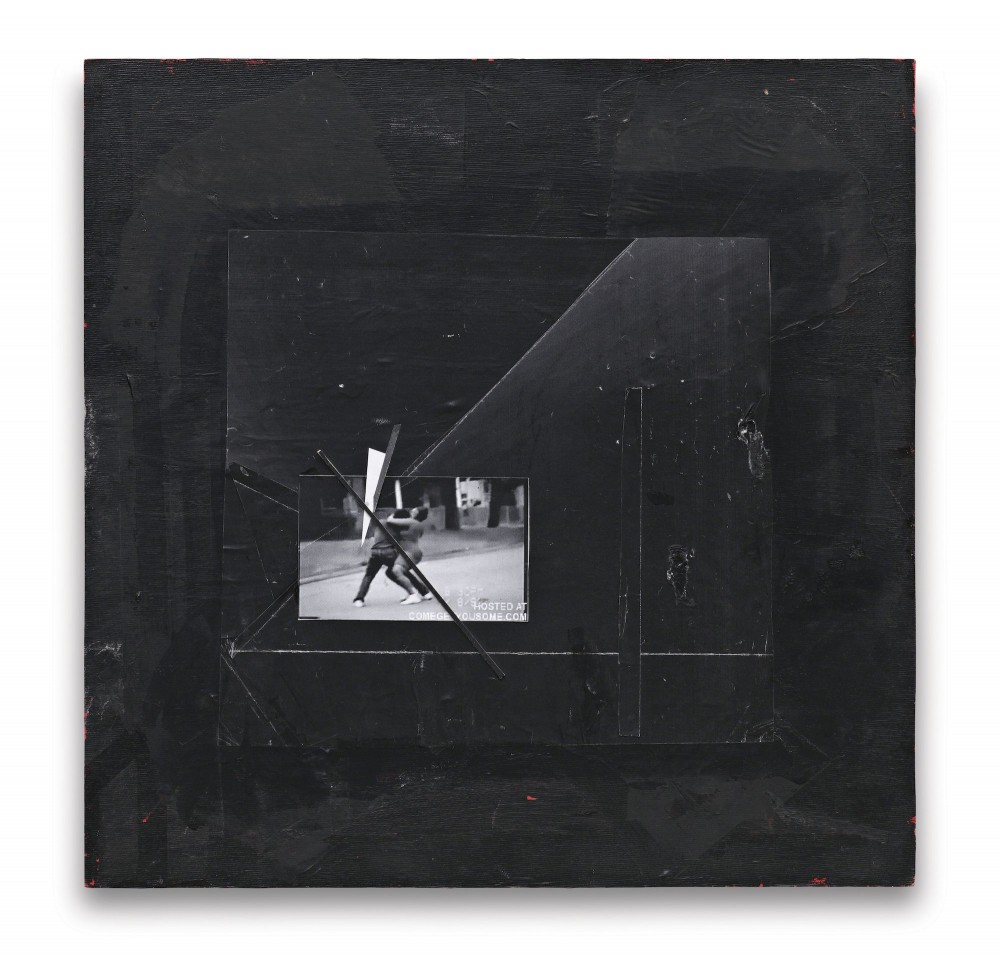

Kandis Williams, Landscape and RFD (2018); Vinyl adhesive collage on plexiglass; 21 x 21 inches. Courtesy the artist and Cooper Cole Gallery.

I love the use of a Greek mythological figure as a reference. As someone who travels so deep into the history of literature and philosophy, how do you make peace with the white supremacy and misogynoir of the Western tradition, the so-called canon? So many of my friends over the years have refused to engage. They say, “That isn’t our history, that shit’s not for me.”

You know the thing I reject and resent bitterly with every fucking bone inside is anyone that says that Black people shouldn’t or can’t read everything. Anything I read is a part of my tradition and my purview. Right now, for example, I’m thinking a lot about the Bolshevik Revolution, the political history of Russia, and what it meant for a peasant class to confront oligarchy again and again. That’s all a part of our history as human beings, and simply because it didn’t directly happen to Black folks doesn’t mean that it doesn’t tell us a tremendous amount about what we’ve faced here in America as a peasant class confronting an oligarchy of our own.

I’m thinking of all the white professors and classmates I had growing up who imagined themselves as the culmination point of some privileged line of filiation back through Thomas Mann or James Joyce all the way to Plato or Homer. Patently absurd, comedic even. The idea of a continuous European civilization is a scholarly fiction developed by philologists in the 18th and 19th centuries, bound up in the colonialism and racial science of emergent European nation-states.

Yeah, they try to claim all of it. Even figures who aren’t white, whether Charles Mingus or David Hammons or Mao Zedong. They get all of it. And it’s like, “You might have to do a little bit more research.” Look at (Michel) Foucault’s and (Jean) Genet’s relationships to the Black Panthers. I’m not going to feel like parts of the world don’t belong to me. I also don’t think we have to strip the building from the ceiling down to develop, say, a theory on the uneven distribution of labor in this country.

Kandis Williams, Child M/other 1 (2013); Acrylic paint and collage on canvas; 11.69 x 8.27 inches. Courtesy the artist and Night Gallery.

What are you excited about that you’re working on right now?

Watching horror movies again — I am developing a class called Blackness, Dissonance, Terror. It’s an extension or third attempt after the two sections of a class called Whiteness, Dissonance and Horror that I taught this summer. One of the things I’m examining is the long history of black villains in the history of literature, art, and film — from Uncle Tom’s Cabin down to Candyman and now Lovecraft Country. I’ve been thinking about Black anti-heroes like Jack Johnson and Frederick Douglass and non-black heroes of Black authenticity from Bill Clinton to Scarface and Donnie Brasco to desexualized “elegant” Black heroes in pan-racial non-Black or white casts in Blade and Jordan Peele’s Get Out. The pantheon of cameos of witch doctors, voodoo priestesses all grapple with that Baldwin question: why was it necessary to have a nigger in the first place? Even like … Morpheus from The Matrix trilogy.

Right! He is the one chosen to find “the one,” Neo. It does have a very Uncle Tom’s Cabin vibe to it.

Yeah it’s literally Uncle Tom had to be materialized and give his entire narrative life in sacrifice, bonding solely with a white chick before white people shed mainstream white tears over slavery, and it started a war. And that same trope has played itself out again and again — look at this year…

Interview by Chloe Wayne and Mahfuz Sultan

Chloe Wayne and Mahfuz Sultan are the co-founders of Clocks, a research and design office based in Los Angeles.

Images courtesy the artist and Night Gallery unless otherwise noted.