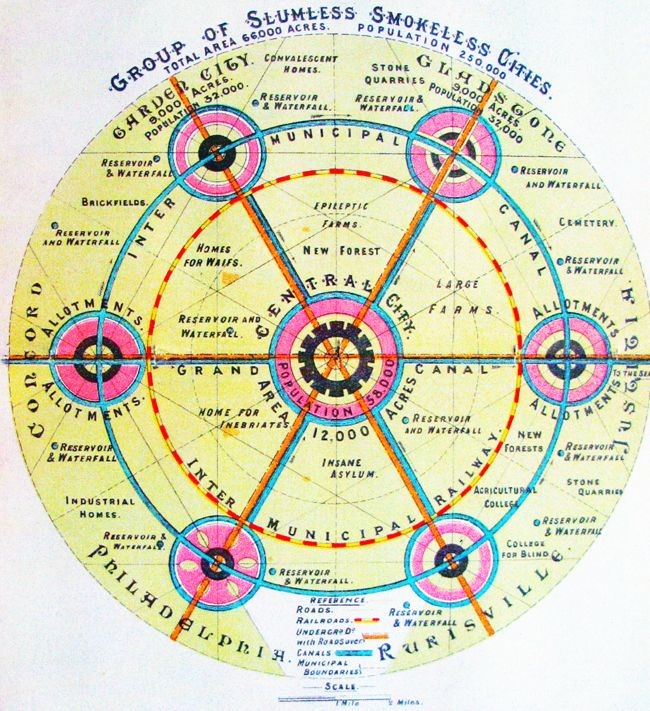

INTERVIEW: The Inner Architecture of David Salle

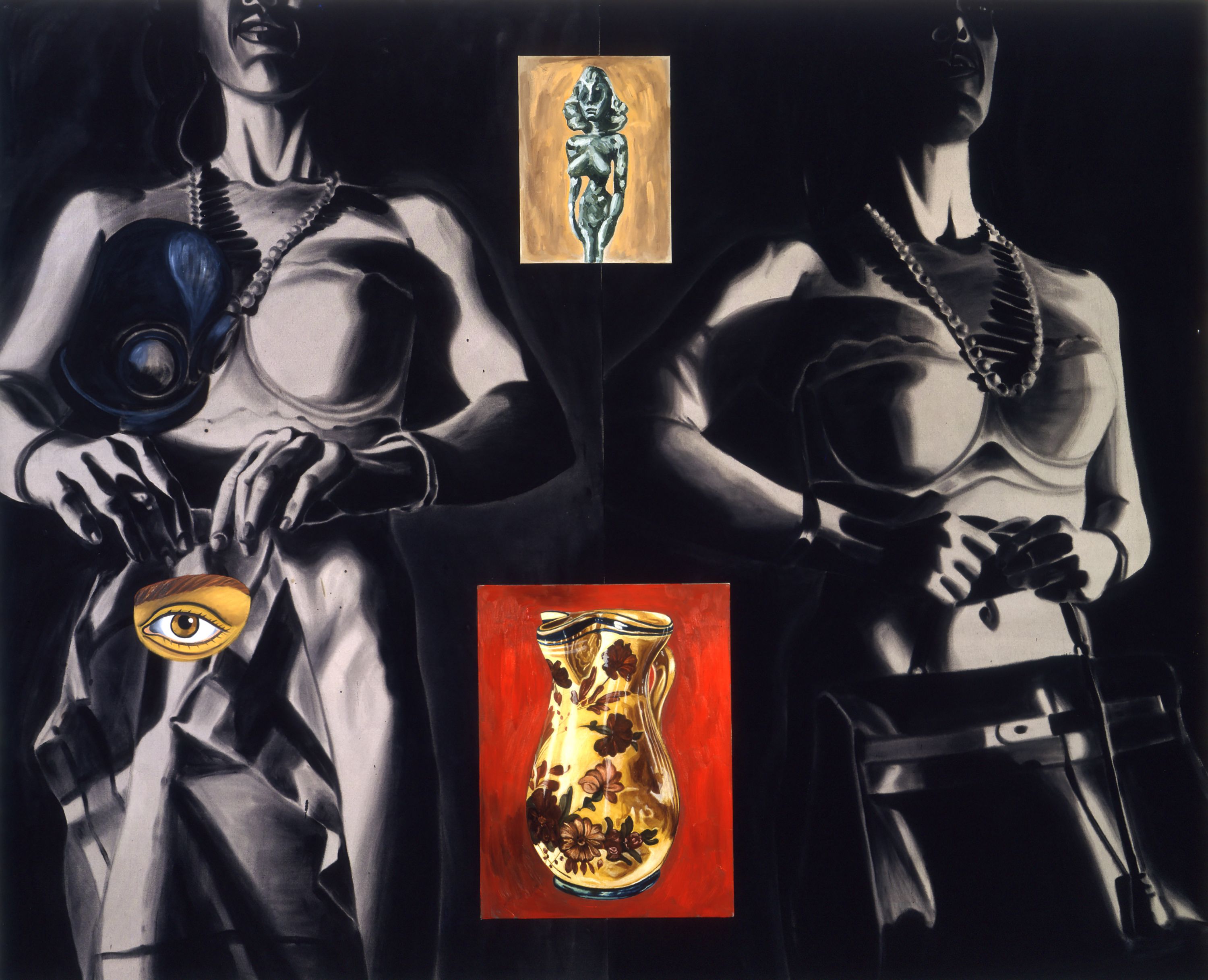

Dean Martin in Some Came Running, 1990-1991. Acrylic and oil on canvas with three inserted panels. © David Salle/VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

When I think of David Salle’s paintings, I see California in its various shapes and colors, Los Angeles, his college stomping ground, and New York, his official landing zone since the 1980s. I think of Learning from Las Vegas, Denis Scott Brown, Robert Venturi, and Steven Izenour’s 1972 book which considers the woes of Modern architecture through its lighting, style, patterns, and symbolism. Salle is infamous for translating words (signs) into images (symbols), or rather staging images that incite specific feelings — memories both made and witnessed.

I last saw his work in Greenwich, Connecticut, at a survey show from the late ’80s onwards. On the train ride up from New York City, I sat with a newly minted arts editor at one of the main art periodicals. He mentioned having recently finished Janet Malcolm’s “Forty-one False Starts,” which I hadn’t revisited since working at the other Magazine, as an editorial assistant, though I had first encountered it in a freshman writing seminar on architecture, art, and design. I was reminded of the Salle New Yorker profile by Malcolm, which is arguably canon, where she details the intricacies of being in the art world. She underlines how essential writers are to measuring the general temperature of the art world’s unforgiving culture. I got halfway through it before arriving at the gathering scene of Salle’s opening at The Brant Foundation.

I wasn’t expecting to be in conversation with a younger version of myself after traveling from subway to train to car, so after drinks and niceties at the opening, I made for a quick exit and took the shuttle back to the train station. The van ride was quiet. I was alone with two women, all of us seated in our respective rows. As we arrived at the station, one immediately dashed away on foot and the other and I made home at two separate ends of the same wooden bench. She asked if I had been at the show and if so, what I had thought of it. I talked about seeing Salle and Jeff Koons, about making conversation with other artists and critics about who managed to file on time (not me!). I was overwhelmed that this all felt more like a waking dream, so I tried to quiet my mind and focus on the art by breaking down each painting in a piecemeal way.

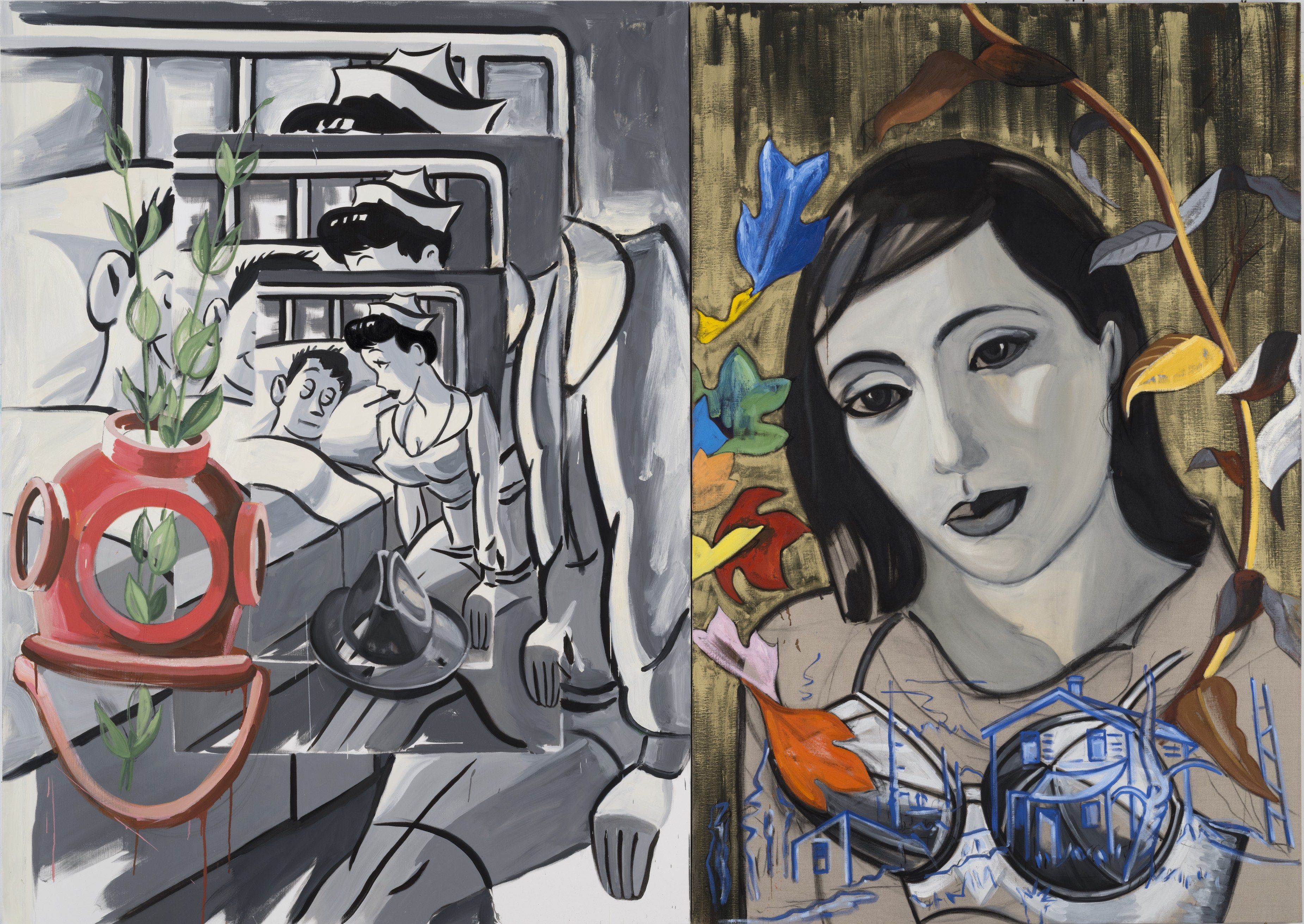

Footmen, 1986. Oil and acrylic with wood bowl on canvas. © David Salle/VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

I didn’t have too much to say to her about Salle’s art because I thought he deserved more than a flip judgment. She told me she was a dancer and a choreographer and that she had a nice life, but her career didn’t amount to her being monied in the same way. We spoke about the art world being able to fit into a small room at one point and how she felt that there was just too much of everything now, to which I agreed. Most of what I encounter these days either lacks feeling or isn’t too concerned with complicating itself in real-time.

After chatting for a while longer, I nestled myself into a booth alone, played my music, and resumed reading the Janet Malcolm profile on Salle when I encountered what seemed like a parallel fiction to the woman from the train station. In vignette “32” Malcolm notes of Salle’s then-girlfriend Karole Armitage, a dancer and choreographer who was a lead in Merce Cunningham’s dance company before forming her own avant-garde studio. I laughed off the uncanny similarities before doing a quick Google search. I found the same petite figure and pixie cut-framed face of the woman I had been speaking to moments before. Though I managed to leave the “set” of Salle’s opening before making my way through Manhattan, I felt like I was living in a world of someone else’s design. All of these chance encounters mirrored the taxonomy and architecture of Salle’s world-making through painting. The whole experience left me perplexed and wanting to engage Salle himself, in his own words. We spoke in February via email about what it means to have a studio practice, desire, general art and theory things, along with his relationship to writing.

Emmanuel Olunkwa: What is your relationship to art now? Who do you make work for? Is the problem you’re trying to solve the same question you started asking yourself while at CalArts?

David Salle: On one level the problem is the same: how to make something interesting to look at that also has some inside energy. In principle, I make work for everyone — that is to say, one only has to be willing to look in order to engage with one of my paintings, but of course not everyone has to like it.

Do you spend much time looking at art? Is it something you believe in or is it all you know?

I may not see everything, but I’m always looking to be knocked out, and you never know where it’s going to come from. I just finished writing a piece about the painter Rose Wylie, who is just now becoming widely known at the age of 87. So yes, I believe in art, all the arts really. The ability of art to elevate, vivify, challenge, surprise, and focus attention; in other words, to give form to complex feelings and ideas — all of it. To refract experience into a condensed gem of expression — what else do we have?

Installation view of David Salle at The Brant Foundation. Photo by Tom Powel.

What is your relationship to writing these days? Is it a point or process of clarification for your visual work or is it its own means to an end, artistically?

It’s both. I like to think that writing is a creative endeavor on its own. Constructing a sentence that has verve and originality and that expresses something specific, a feeling or condition that is hard to name — all of that is ‘artistic’ obviously. I’m making something, the same as I would make something in my studio. It just so happens that I’m writing about art, about what I know. I’m an essayist, and I’m lucky, as we happen to be living in a kind of golden age for the essay form.

Oh interesting. Why do you think we’re living in the golden age of the essay? I agree, I believe that writers are the architects of the moment, they’re going to move, grow, and shape culture in an unprecedented way.

The other notion is also true: I’m writing to figure out what I think about something, and in a broader sense, to consider the forces that helped shape an artist’s sensibility. My own sensibility very much plays into it, but I try, in the writing, to locate a deep empathy for how someone else sees the world.

When you were younger what did having a studio mean to you? Did you feel it was an essential way of legitimizing your practice? Was it a gateway, a bridge, or a container?

I’m not sure I understand the question. The studio is not a legitimation machine — if anything it’s the opposite. I feel I need to justify having it.

Ice Flow, 2001. Oil and acrylic on canvas and linen. © David Salle/VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Beyond your own painting style do you ever envision or know an alternative to your practice? Like is there an aesthetic path that you didn’t take but know well? I read somewhere that you don’t/didn’t draw. Is that true?

Of course, I draw, though I’m not especially gifted at it. Some very good painters have not been drawers. I don’t make preparatory drawings for paintings because I find that they don’t help. But to answer your larger question, making things is, in a way, the record of all the roads not taken. I can all too easily imagine completely different ways of working, or making different types of pictures. That stylistic fluidity — or non-attachment — has actually been a theme in my work from the beginning.

In terms of storytelling, do you have a specific desire for painting? What questions do you have from it as a medium?

Much of my work stems from a “what if” type of proposition. The painting poses a hypothetical question, a kind of “what would happen if...?” situation which the painting finds itself in — and puts the viewer into as well. Think of it as the visual equivalent of the conditional tense. It sounds more complicated than it is. It’s not really all that intellectual; it’s more of a comedic, or even slapstick sensibility.

That reminds me of how the most comedic people are secretly the most serious. It takes such a concentrated effort to produce something easily receptive. What is your relationship to the 1970s and ’80s now? Is there any cultural or conceptual overlap to the art being made now?

I’m not nostalgic if that’s what you mean. Or only a little bit. There is always cultural overlap. We tend to think in terms of decades, but culture doesn’t really work that way on the level of individual artists. It’s a question of what lens you’re looking through — there are so many ways to frame this. One view is that artists in the modern era are concerned with maximizing freedom, and much of the art of the ’70s came to feel very constricted. To a certain extent, the ’80s were about trying to expand the freedoms, the permissions of what could be done. The same as in the 1910s and 1940s and so on. I don’t feel that to be as much of an issue today, as there is no stylistic hegemony to react against. Today we have plenty of freedom, plenty of available narratives, but perhaps less depth. It’s the way culture has developed generally: something for everyone, but few things that transcend one group or demographic.

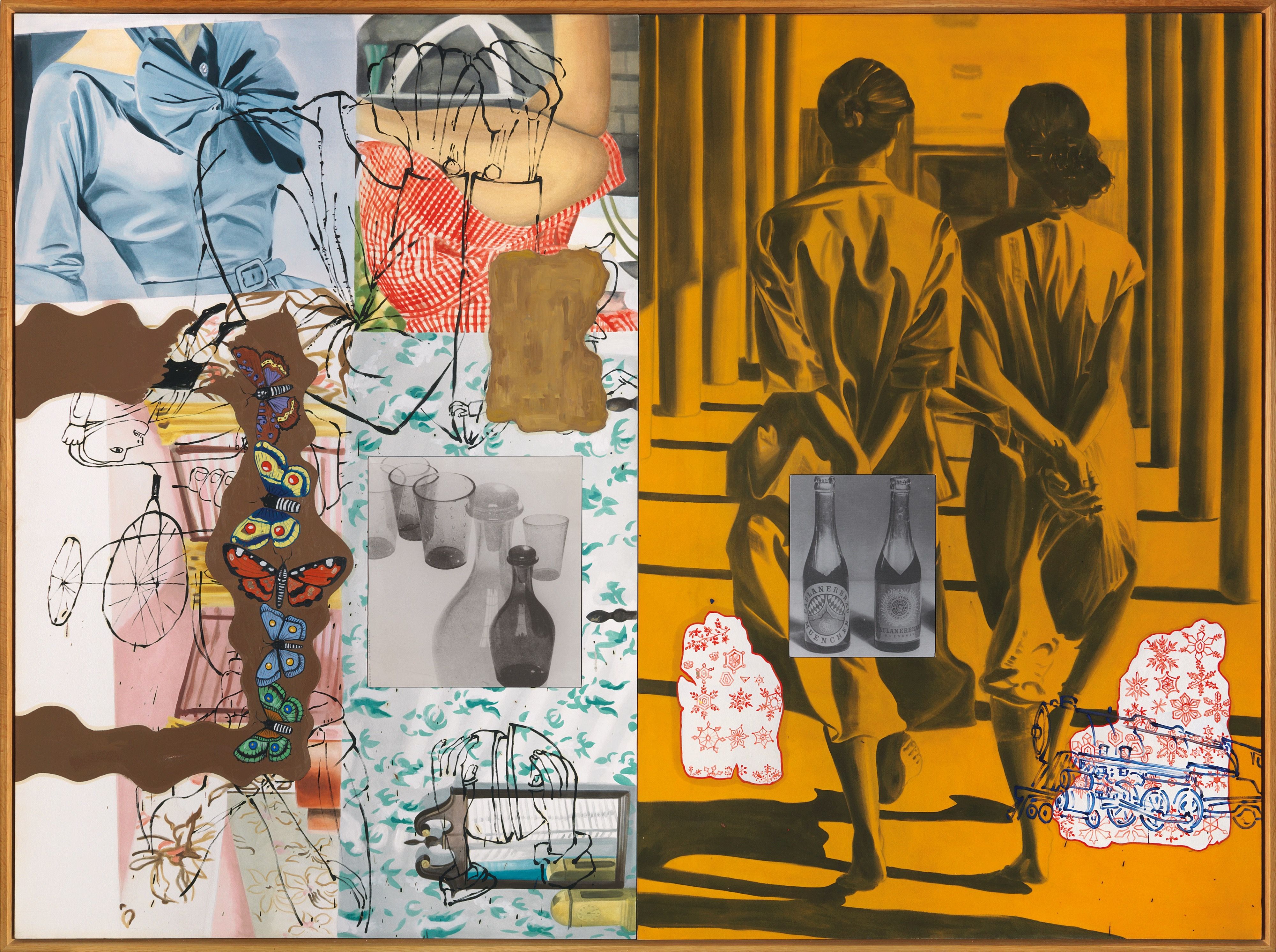

The Kelly Bag, 1987. Oil and acrylic on canvas. © David Salle/VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Does that frustrate you? I feel like we’re living in the age of the aesthetic of aesthetics. Everything just gestures at something else but there is no singular whole, like a pitcher or container that holds water. It seems like everything is just an image or representation of the real thing. Very few objects and experiences hold things and people. What lens are you looking through if you’re nostalgic? Do you feel like you are from the ’80s or is that just when you came into consciousness by thinking in public in such a specific way?

It is frustrating. I don’t personally feel that I am of the ’80s or any other era particularly; I’m me.

What is your relationship to architecture? Is space something that you think about outside of thinking through color and light, leading to varying object formation?

My work is not site specific. I love architecture and love thinking about it, both as experience and as an image, and of course paintings are meant to be seen in a real place, not just as disembodied images, but I don’t take my cue from architecture.

How many paintings do you make a year now? In the 1980s you made 20; has that changed?

I don’t really keep track. Every year is different. The work is somehow self-regulating on that score, like the number of Joshua trees that can co-exist on a given piece of terrain. There is only so much water which they all have to share.

What did you want from art when you first started? What did you want from painting?

Probably what everyone wants: something with a strong identity that expresses a sense of being alive in this particular moment, but without resort to illustration. Initially, I just hoped to make something that was free of cliche or received ideas. At the beginning, I think I was ‘using’ painting; ultimately, one wants to ‘merge’ with it.

Have you merged or are you still using it?

Oh, we merged a long time ago.

Equivalence, 2018. Oil and acrylic on linen. © David Salle/VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

How would you situate painting as a medium in the current cultural landscape of art production?

Well, the question is an interesting one — it supposes that an individual medium can be subject to a critique, or that some media are more appropriate to a particular time than others. I just don’t think about that very much. Or rather, I don’t pay attention to any directive about what is or is not appropriate today. I strenuously disagree with those kinds of strictures. The artist makes it appropriate, whatever it is. Painting is both skill and a talent — and also a culture — a way of life, a continuity. I don’t personally feel that anything can compare to painting when done at a high level, though obviously you can make art out of anything, or with anything. The fact that painting’s primacy might be an inconvenient truth for some critics or theorists doesn’t faze me at all.

Is painting the only inconvenient truth? If not, what would some other examples be?

Oh god, there are so many. Or perhaps better to say there is one overwhelming one, which is the fallacy of intentionality, which I have written about at some length.

What are you trying to communicate with the subject matter in your paintings now? Are you still concerned with the presentation of objects or has that shifted? Is it about form, technique, color, composition, or memory?

It’s about everything — all of it. All those things together make up a sensibility, which is ultimately what we have to work with.

Do you think about narrative? What is your relationship to storytelling?

I think my paintings are highly narrative, but perhaps not in the conventional sense. I love narratives that seem to lose their way, only to find it again later on. I love back-stage narratives too, and I like to think about what the painterly equivalent might be. In the beginning I was trying to drive a wedge between something and the name for that thing — to open up a little bit of space so as to slow down the automatic connections between word and image. I’m still doing that, but now I’m doing other things too.

Old Bottles, 1995. Oil, acrylic, and photosensitized linen on canvas. © David Salle/VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Why did you move to New York after CalArts and why didn’t you move to Los Angeles?

Actually, I was living in LA then — in Venice to be precise. In those days, LA was not seen as a viable alternative to New York.

Oh, Venice. What was happening in Venice at the time? Did you spend much or any time at Ferus Gallery?

That was before my time. When I was there, Irving Blum, who had run The Ferus Gallery, had already opened his own blue-chip gallery on La Cienega. But Venice itself was lovely, and sleepy, like a little village.

What is your relationship to desire?

Desire is a great driver of art — not exactly news. I know this has become ‘problematic’ as they say, but it’s part of life.

Do you still think of painting as a way to mirror itself?

I’m not sure I ever thought of it that way. There’s a mirror in there somewhere, but not sure where.

What should painting communicate now?

More life.

What’s your relationship to fascism now? In your 1981 interview with Peter Schjeldahl, you speak about your generation being more fascistic than previous ones because it took what it liked as a kind of given, instead of wondering why it liked what it did?

Well I think the idea is true, but the use of that word is just incorrect. I loathe anything that smacks of fascism, an all too present danger at the moment, from the left as well as from the right.

The Old Bars (after MH), 2017. Oil, acrylic, flashe, charcoal and archival digital print on linen. © David Salle/VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

What’s your process like? Are your works constructed around context and concept or do they come together as fragments pieced together to make a whole?

My process is intuitive, and improvisational. It’s essentially additive play.

What is your relationship to exhibition-making? When you’re making paintings do you think of them as singular universes or worlds occupying the same space, or do you think of them as the variables that are taking shape to present a legible essay?

Both.

What are your feelings on sentimentality and feeling?

It’s complicated to talk about. One wants to avoid sentimentality obviously, but it has its uses, like kitsch. True sentiment — not sentimentality — is an aspect of art’s tragic dimension. Sometimes it’s hard to tell the difference, but we have to try.

I love kitsch. I wish we had more of it today and witnessed more sincerity. The market lacks sincere objects and experiences these days.

Oh really? I thought we had entered the post-irony world. But sincerity is one of those things about which there is little agreement.

What did you think of Roy Lichtenstein and his use of presentation in terms of context and style? You use collage as a form of presentation but is your technique a direct response to someone else’s style? Is your style born out of any resistance?

You’re right. Roy and I both ‘use’ style as something to build a painting around, or as something to bend into a painting. There’s a certain pleasure in that, in the impersonation. I’m not so much interested in references for their own sake, however. Nor was Roy. An image has to mean something, usually on more than one level. It has to be attached to the past and also free of it, if you know what I mean.

Is it ever concerned with the future, or is that something the work just encounters when it’s ready and people can finally see it for what and as it is?

I wouldn’t want to be too grandiose about it, but some notion of that is sort of built into the work.

Is improvisation something you’re still thinking about?

Very much so.

What is your relationship to literature and film? Do you believe that these categories such as surrealism and minimalism have much of a presence in terms of style presently?

All these categories are really markers of sensibility, of taste, and as such will always be with us. It’s a matter of how they are used, or inhabited.

Interview by Emmanuel Olunkwa.