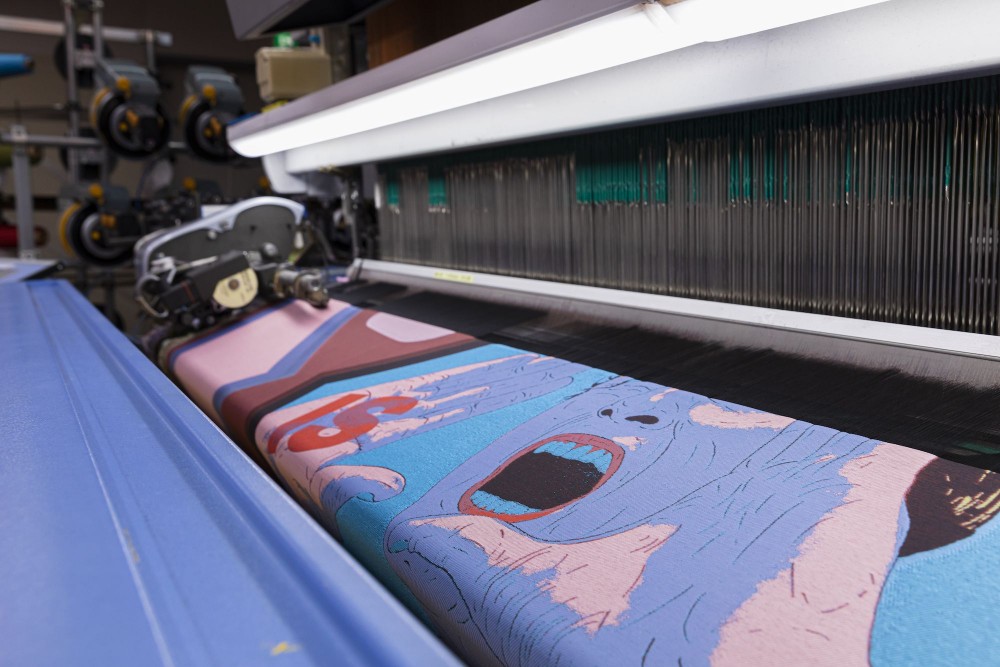

Artist Tadanori Yokoo On His Latest Collaboration With Issey Miyake

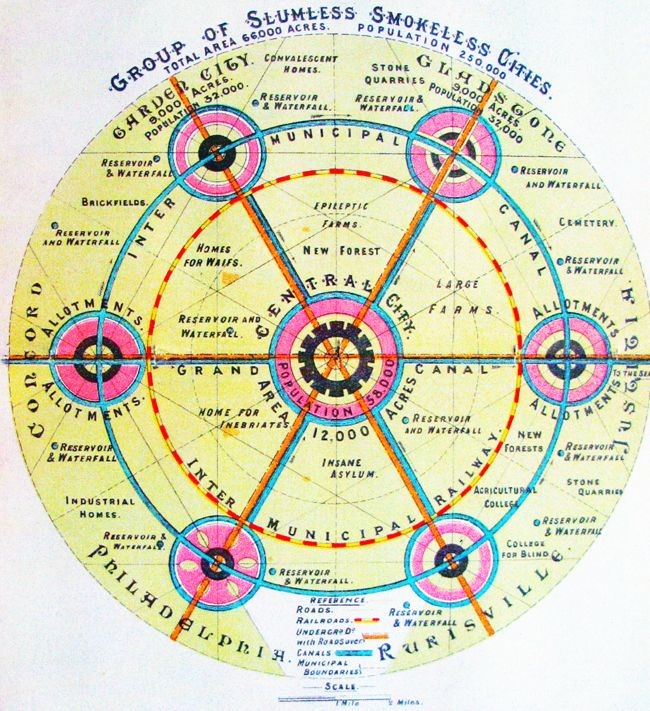

Invitation to the Issey Miyake Fall Winter 1979/80 collection designed by Tadanori Yokoo. Image courtesy Issey Miyake.

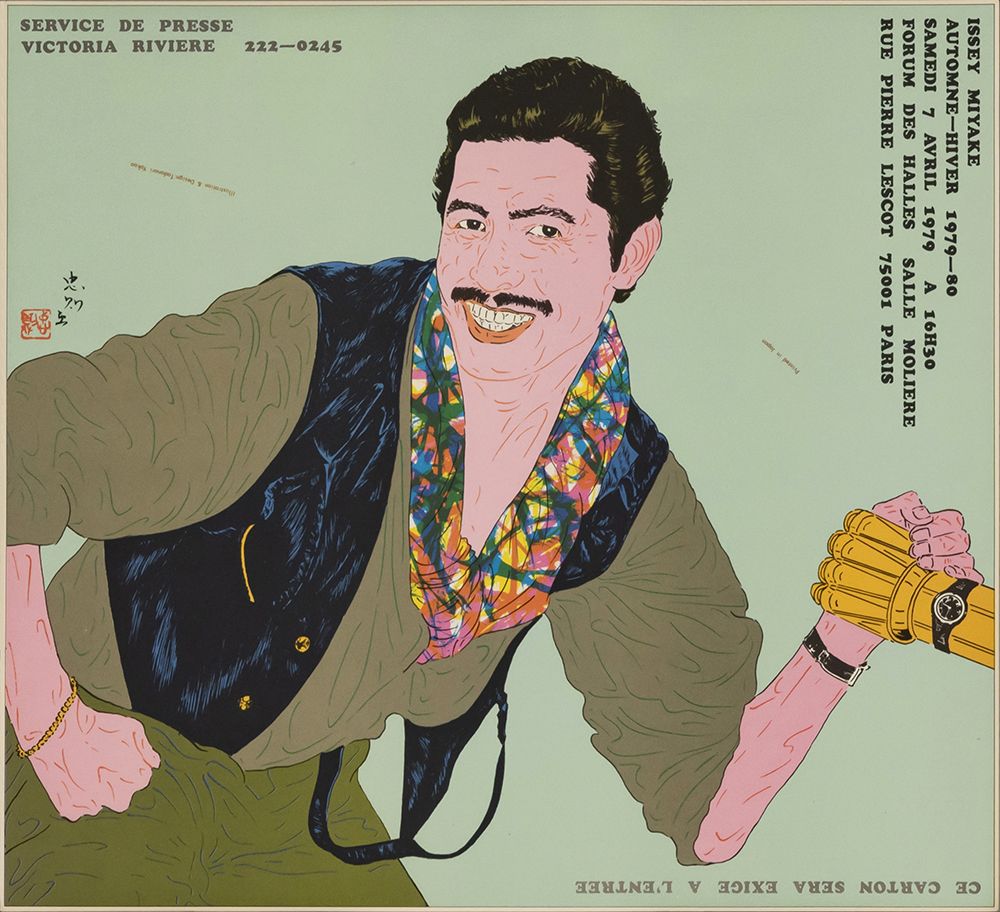

The Japanese artist Tadanori Yokoo and the fashion designer Issey Miyake have been close collaborators for decades. It started in the 1970s, when Yokoo began designing the invitations for Miyake’s memorable fashion shows in Paris, often rendering the designer’s handsome portrait in Yokoo’s psychedelic pop art style. Both men are now in their eighties, but neither is showing any signs of slowing down. Their latest project is a collection of blousons that translate eight of Yokoo’s paintings — some dating back to the 1960s — into beautiful wearable textiles. To produce the collection Miyake Design Studio employed A-POC, a signature manufacturing process started in 1998, using computer technology to create clothing from a single piece of thread. (A-POC stands for “A Piece of Cloth.”) As the line of blousons is making a splash across Japan and online, PIN–UP was able to reach out to the octogenarian master to answer five questions.

-

Blouson from the Tadanori Yokoo Issey Miyake collection featuring artwork adapted from Yokoo’s painting Tarzan is coming (1974). Photography by Hiroshi Iwasaki. Courtesy Issey Miyake.

-

Blouson from the Tadanori Yokoo Issey Miyake collection featuring artwork adapted from Yokoo’s painting Moat (1966). Photography by Hiroshi Iwasaki. Courtesy Issey Miyake.

-

Blouson from the Tadanori Yokoo Issey Miyake collection featuring artwork adapted from Yokoo’s painting Drool (1966). Photography by Hiroshi Iwasaki. Courtesy Issey Miyake.

Under what circumstances did you first meet Issey Miyake?

I first met Issey Miyake in May 1971 while I was staying in New York. I was invited to an Issey Miyake fashion show at Japan Society through a mutual friend and I met him backstage, although we only exchanged a few words in greeting that time.

What was it that ignited your longstanding and collaborative friendship?

Soon after returning to Japan, I was asked to design his Paris collection invitations. What we have in common? It doesn’t matter that we work in different genres. It’s a matter of whether we can respect the act of creating. Issey-san has always continued to incorporate new changes in his creations. For me, creation is an accumulation of changes. Issey-san’s ever-changing work inspires discoveries and developments within me.

-

The programming technology of knitting/weaving fabric by giving every thread an instruction has continued to evolve since A-POC was first created in 1998. Photography by Ooki Jingu. Courtesy Issey Miyake.

-

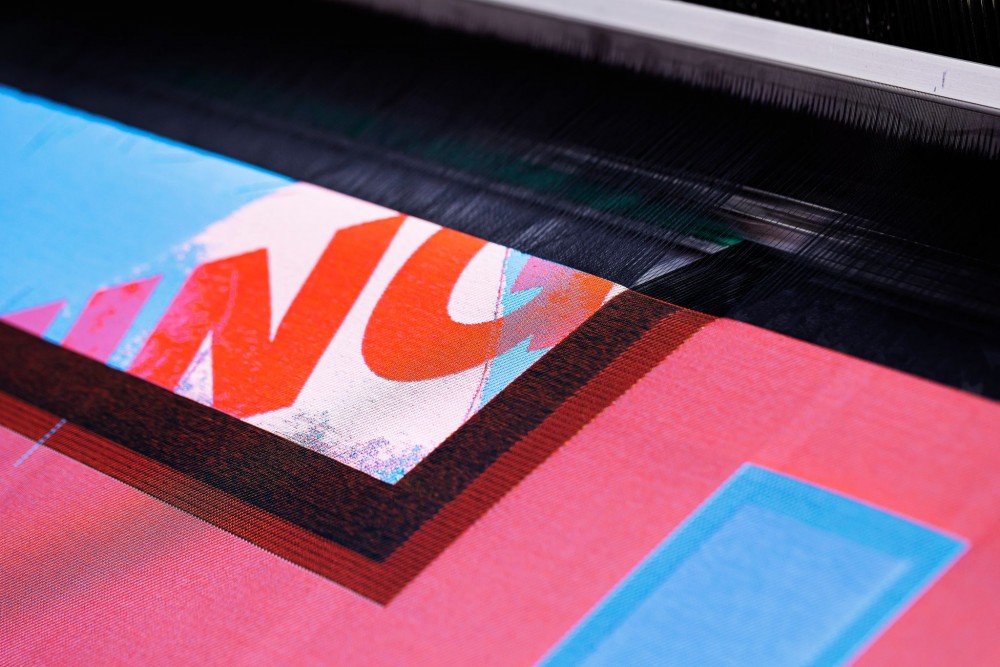

A computer-controlled digital loom makes possible the A-POC manufacturing process. Photography by Ooki Jingu. Courtesy Issey Miyake.

-

A-POC, the acronym for “A Piece of Cloth,” is the manufacturing process shown here, completing a design while the fabric is made from a single thread. Photographed by Ooki Jingu. Courtesy Issey Miyake.

You and Miyake-san helped pioneer a new postwar Japanese aesthetic — in design and fine art. Though working in different mediums and disciplines, surely your work share overarching ideas and fundamental concepts. What do you think they might be?

In 1980, I made the transition from being a graphic designer to being an artist. Graphic design is work, but being an artist is life. It has a direct connection to living. Graphic design is an advertising medium for products, but painting doesn’t have any purpose in itself. If there is a purpose, it is the act of painting itself. For fashion, wearing the clothes themselves is the purpose. Therein lies the difference between the two, but a characteristic of Issey-san’s work is that the forms of his work have an aesthetic beauty. In that sense, I think they can rightly be called works of art. Issey-san’s fashion could pass as sculptures. It has that in common with art.

-

Blouson from the Tadanori Yokoo Issey Miyake collection featuring artwork adapted from Yokoo’s painting Bride (1966). Photography by Hiroshi Iwasaki. Courtesy Issey Miyake.

-

Blouson from the Tadanori Yokoo Issey Miyake collection featuring artwork adapted from Yokoo’s painting Razor (1966). Photography by Hiroshi Iwasaki. Courtesy Issey Miyake.

-

Blouson from the Tadanori Yokoo Issey Miyake collection featuring artwork adapted from Yokoo’s painting panic Panic PANIC (2002–12). Photography by Hiroshi Iwasaki. Courtesy Issey Miyake.

For many years you created the invitations to Issey Miyake’s fashion shows. For many years the invitations featured the likeness of Issey Miyake himself. What was the thinking behind doing portraits of Miyake-San? Why did you stop?

The reason I painted portraits of Issey-san for the Paris collection invitations is because what connects a creator with their work is physicality. A portrait isn’t simply a facial likeness. It’s a depiction of the body. I stopped painting his portraits possibly because Issey-san himself felt a certain resistance to having the star quality of Issey Miyake being emphasized. In later years, it seems that Issey-san reflected that he should have continued with the portraits. As with the changes in his work (fashion), his likeness would change over the years through repeated depictions. I believe constant change is true beauty.

-

Fabric made from a single thread using the A-POC process, featuring an adaptation of Tadanori Yokoo’s painting Razor (1966). Image courtesy Issey Miyake.

-

Fabric featuring an adaptation of Tadanori Yokoo’s painting KEY BEAUT.Y. (2017), before being cut and sewn to create a blouson. Image courtesy Issey Miyake.

-

Fabric featuring an adaptation of Tadanori Yokoo’s artwork produced using the A-POC process, before being cut and sewn to create a blouson. Image courtesy Issey Miyake.

-

Fabric made from a single thread using the A-POC process, featuring an adaptation of Tadanori Yokoo’s painting Razor (1966). Image courtesy Issey Miyake.

-

Fabric featuring an adaptation of Tadanori Yokoo’s painting Drool (1966), before being cut and sewn to create a blouson. Image courtesy Issey Miyake.

-

Fabric featuring an adaptation of Tadanori Yokoo’s painting Tarzan is coming (1974), before being cut and sewn to create a blouson. Image courtesy Issey Miyake.

-

Fabric made from a single thread using the A-POC process, featuring an adaptation of Tadanori Yokoo’s painting panic Panic PANIC (2002–12). Image courtesy Issey Miyake.

-

Fabric made from a single thread using the A-POC process, featuring an adaptation of Tadanori Yokoo’s painting Moat (1966). Image courtesy Issey Miyake.

Your vibrant work and Miyake-san’s ingenuity are together again in a new collection made from the iconic A-POC series. Just as an artist oversees reproductions of their work in prints, either though lithography or intaglio, you are also looking at your work in editions of dye and fiber rather than ink and paper. Has the shift in material and medium revealed anything interesting or surprising about your own work?

My early paintings from the 1960s were used for the A-POC blousons. They aren’t complete replicas of the originals. With the use of a new material of woven fabric, their colors and forms changed. Those changes made them separate from the original paintings. On top of that, two-dimensional paintings were converted into three-dimensional clothing. They gained physicality and have been transformed into art that moves in an urban setting. It is a moment that connects art and fashion within urban living.

Interview with Jeremy Lewis.

All images courtesy Issey Miyake.