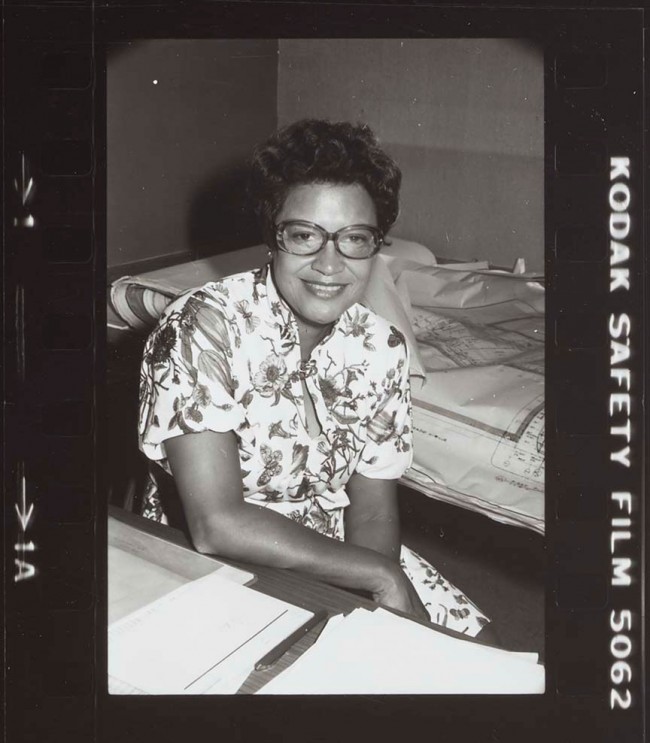

INTERVIEW: Amina Blacksher On Favelas, Robotics, And Teaching Architecture

From designing a robotic arm for jumping rope and hosting a docuseries to researching the construction techniques of Brazilian favelas, Amina Blacksher’s practice is panoramic. The New York-based architect and principal of Atelier Amina grew up in Ithaca, NY, without a TV — instead she and her siblings sat in on lectures at Cornell University for fun. Blacksher went on to complete a masters at the Yale School of Architecture and today teaches at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation. This winter Blacksher made her third trip to Brazil for an immersive residency studying approaches to building at the Morro da Babilônia favela in Rio de Janeiro. Motivated to expand on and challenge the inherent hierarchies of her formal training and professional experience, she will channel the knowledge gained on the trip into both a documentary short and a journal article. Blacksher talked to PIN–UP about the fundamentals of her practice.

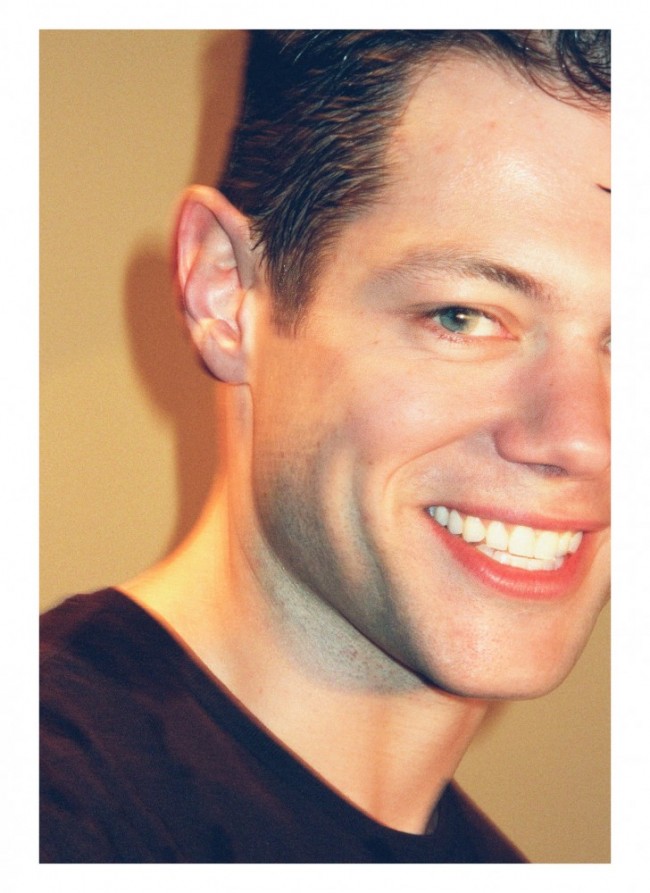

Amina Blacksher designed a robotic arm that turns two jump ropes in opposite directions simultaneously.

Amina Blacksher’s Robot Double Dutch project explores proprioception, precision, and rhythm.

Ashley Valera: What does architecture mean to you?

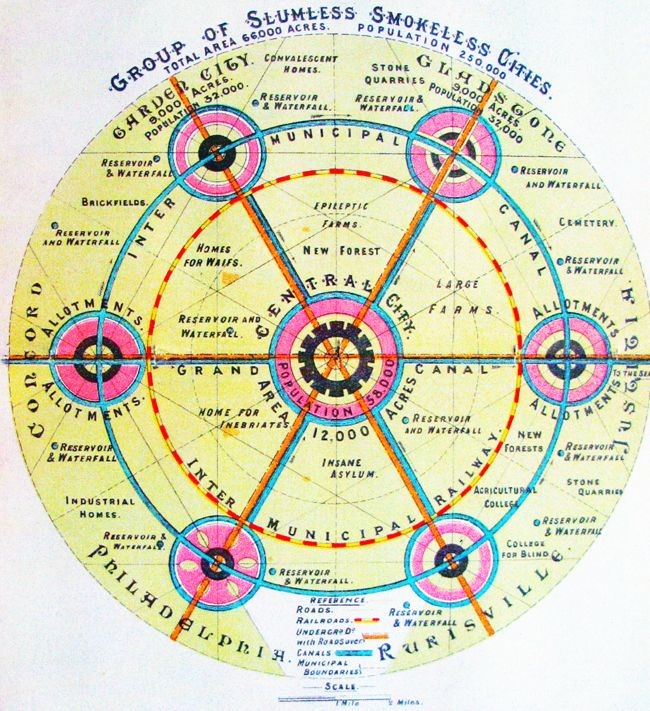

Amina Blacksher: That’s the 64-million-dollar question for me right now. I’m currently studying innovative construction techniques in the Morro da Babilônia favela in Rio, and it’s cracking open everything I thought architecture was. Even a month ago I might have defined it as drawings. Drawings are representational of an intent, but they’re also documents that convey instructions. In the environment I’m in right now, there are homes being built all around, on the side of a mountain, that don’t use drawings as instructions. It’s another way of communicating design intent. Also, in the climate conditions I’m used to, architecture protects you from the environment and creates an enclosure that is almost airtight. In this tropical environment, that is not necessarily the objective. Buildings can be completely open to the air and the only protection needed is from rain. That to me means that architecture is horizontal and vertical but it doesn’t need to be sealed at the seams. It’s really been breaking open my concept of the envelope and the shell or skin of a building.

-

This winter Amina Blacksher studied construction techniques at the Morro da Babilônia favela in Rio de Janeiro.

-

At the Morro da Babilônia favela in Rio, Amina Blacksher explains, “homes are being built on the side of a mountain that don’t use drawings as instructions.”

-

Amina Blacksher plans to channel what she learned about favela construction techniques into an episode for her architecture docuseries as well as a journal article.

What has your experience teaching at Columbia brought you?

It’s really a sacred role to be in, to transfer information. It’s made me more aware of what is essential to pass on. I always start with the brilliance of the student. I’ve learned that it’s not something that the teacher instills or instructs. The best I can do is lead by example and bring out the students’ vision and hone it. It’s really a great collaboration. My mom has been a teacher for over 25 years. She always told me I have to teach — that was good advice.

You were a dancer before becoming an architect. Has dance informed your design practice?

I did ballet for 15 years and modern and African dance later on. It gave me a foundation in seeing form as something that isn’t static. In architecture, we tend to think of form as a noun. I also like to think of form as a verb. I wonder why we rely so much on a Cartesian system and a language of expression where everything has to be straight and at 90-degree angles? I like to think of form as a snapshot in the continuum of motion. Architecture does ultimately want to be fixed, but it doesn’t have to come out as straight lines and right angles. It can be an extracted moment in a continuum of force and mass negotiation. Even when buildings are constructed, the logic is that they are still negotiating forces.

Amina Blacksher photographed in Rio de Janeiro. Portrait by Pedro Bucher for PIN–UP.

On the topic of movement, your Robot Double Dutch project is so nuanced. How did your cultural background find a voice in your work?

I got the platform to contribute an entry to Princeton’s 2019 Black Imagination Matters conference through a good friend, assistant professor V. Mitch McEwen. I was like, “I have this idea of a double-Dutch robot. It’s kind of off the charts, is it possible?” Double Dutch is a very simple but precise jump-rope game. I had the fortune to read a book by ethnomusicologist Kyra Gaunt (The Games Black Girls Play: Learning the Ropes from Double-Dutch to Hip-Hop) on the embodied formulas that black girls bring to the game. Just like a musical instrument can be in tune or out of tune, there is an innate sense of right or wrong. There’s a required precision that doesn’t allow for error, but then it seems very simple. It’s just two synchronized ropes going in opposite directions — like what could be more self-explanatory? Then the question was how do I approach this game through robotics, which we tend to think of as the ultimate in precision. I was interested in bringing the body into the conversation. The body in the African-American experience holds a lot of memory and information. A lot of times the only thing that people had was their body, when their homes, histories, and families were taken. So the body becomes an important vessel for information and knowledge. I was interested in seeing if I could use technology as a way to dance architecture. The double-Dutch robot touches on the basics of the verb rhythm. The first stage of the project was exploring what it might be like to dance in a rich multi-dimensional gravity-ruled environment as a starting off point for conveying design intent.

Amina Blacksher and V. Mitch McEwen demonstrating the robot’s capabilites at Princeton’s 2019 Black Imagination Matters conference.

Where will you take the project next? I’m thinking in the next few years we’ll be looking at more multi-dimensional design tools and technologies. There are many different ways of arriving at a built form. For example, there were many questions left unanswered with the coordination of the two arms. Could they be controlled by one brain, one computer that can understand its left and its right? I’ve been interested in proprioception, that sense we have of knowing where each part of our body is in space. When you clap your hands above your head, they know where to find each other without your having to look. It’s that sense of self-awareness in our body. There’s great potential in teaching proprioception to machines: robots are good with precision and humans are good with creativity and innovation. So how can these two be used together? My approach is not looking at what a robot can make — I’m looking at robots as friends.