INSIDE THE BUBBLE: A Eulogy For Instagram, Inflatables, And The Innocence Of The 2010s

“The receptive, supportive community that recognizes you for who you are mingles uncomfortably alongside the advertisers that hope to persuade you to be something more, that are eager to hijack the self you share and make it a brand partner to help sell product.” — Rob Horning in “Social Media, Social Factory,” The New Inquiry, July 2011

I gotta be honest... I haven’t scrolled Instagram in months; it’s dead. As with most things, it started off fun, but death is the one certainty in life.

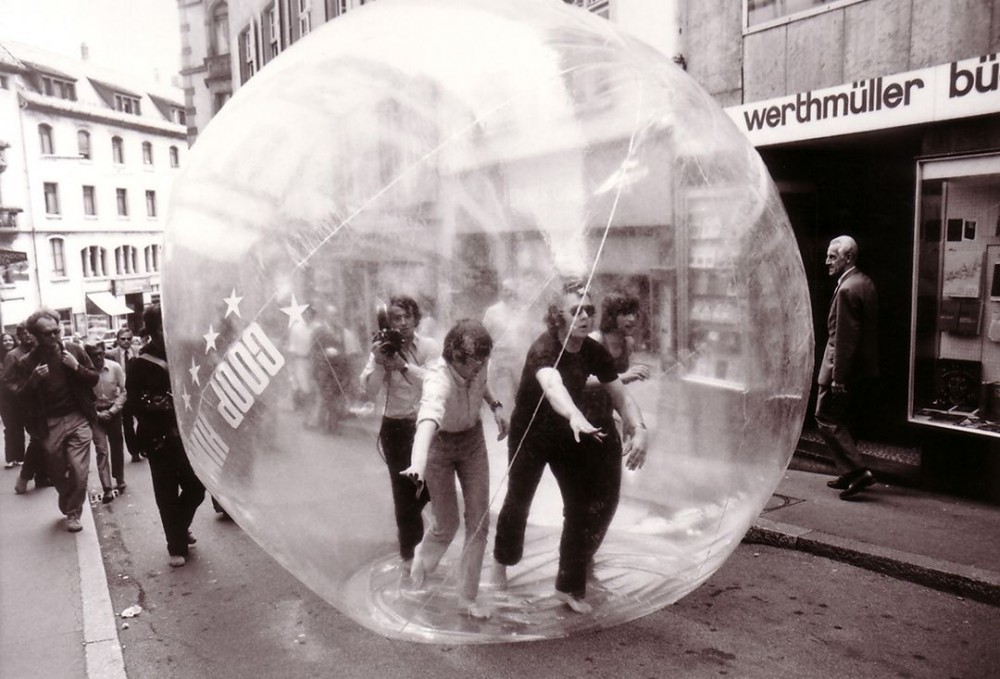

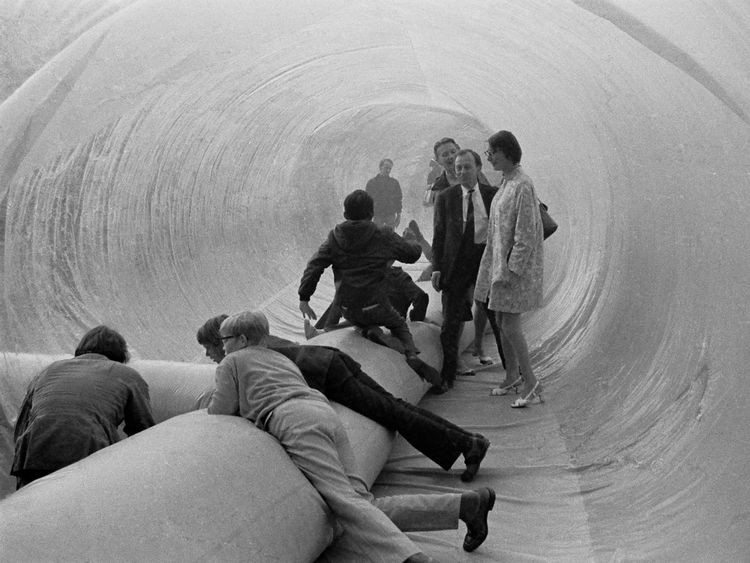

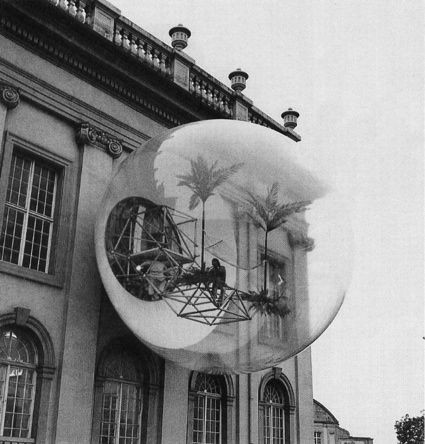

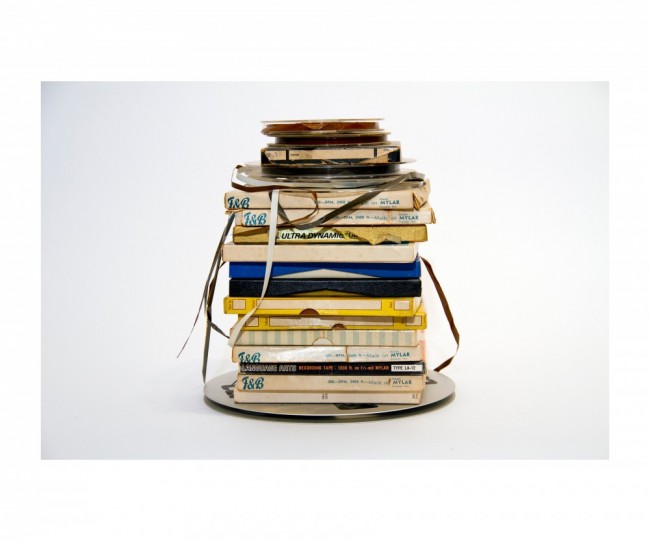

Pneumatic Index circa 1960s or 70s.

What follows is a eulogy as one would deliver at a funeral. Well, three eulogies really: for Instagram, inflatables, and the innocence of the 2010s. My sincerest apologies if Instagram’s death comes as surprising news, but it is in fact zombie software, having had Snapchat and TikTok grafted onto its undead body, relentlessly inducing visual consumption, just like the 2010s trend of inflatables being the default for anything large in live entertainment, and society’s innocence and naïveté in believing in the possibility of having and showing off an authentic self. Don’t worry though, it’s not (entirely) Instagram’s fault, or because inflatable creations were malevolent, or even due to anything you could have ever done to be more authentic. These decisions were made collectively, and therefore they are beyond your agency as an individual to effect, just like climate change.

Instagram is Dead, Long Live Instagram!

I thought that when Instagram introduced advertising in late 2013 that it was actually fun for a while, as a kind of novelty. Like Fortune 500 companies advertising a car to me, a New Yorker without a driver's license, I found it cute, quaint even. But in my case Instagram’s transformation into a virtual suburban mall took a surreal turn through a ghost in the machine.

Advertisement for a jumbo water walking ball.

I joined Facebook in 2005, my summer between high school and college, and deleted my account in 2015, marking ten years of participation in this collective sociological experiment to “make the world a more connected place.” But curiously, in that span of time, when I was living in New York, Montreal, New Jersey, and Brussels, my Facebook metadata was stuck right in the middle, frozen when I was living in Brussels from 2009 to 2010.

It might help to recount the intertwined history of these networks, Instagram and Facebook, though they are really just the same thing with different skins now. Today so many make their livelihoods with and structure their lives around this super-network, and this history may help us to understand how we got here within a decade, what it means, and where we might go next:

- April 9, 2012, Facebook bought Instagram.

- October 24, 2013, just over a year and a half later, Facebook introduced ads on Instagram.

- March 15, 2016, Facebook announced that Instagram’s feed would be algorithmically edited and sequenced, instead of chronological.

- August 23, 2016, Facebook launched a version of Snapchat’s Stories on Instagram, called, unoriginally, Stories.

- November 10, 2016, Mark Zuckerberg says “I think the idea that fake news on Facebook... influenced the election in any way is a pretty crazy idea.”

- March 1, 2017, ads were introduced into Stories.

- September 2018, Instagram’s co-founders Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger announced they were leaving Facebook.

- 2017–20, the rise of influencer marketing culture coincides with the exponential growth of QAnon and other anti-semetic and anti-science conspiracy theories on Facebook and Instagram.

- August 5, 2020, Facebook introduced a version of TikTok on Instagram, this time giving it an original but predictably bland corporate-speak name: Reels.

- October 2020, Facebook changed Instagram’s interface to highlight the shop button, to the outcry of users.

- January 2021, Facebook and Instagram’s parent company FACEBOOK announced plans to change its terms of service for Whatsapp to expand targeted advertising across platforms, triggering a mass exodus of users to privacy-centered platforms like Signal and Telegram.

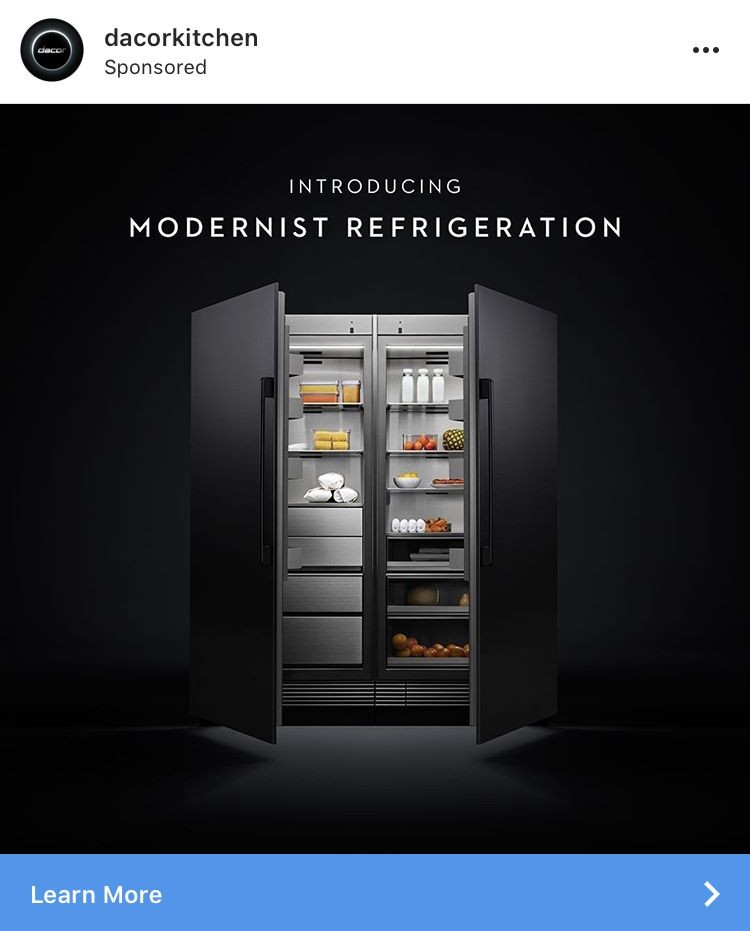

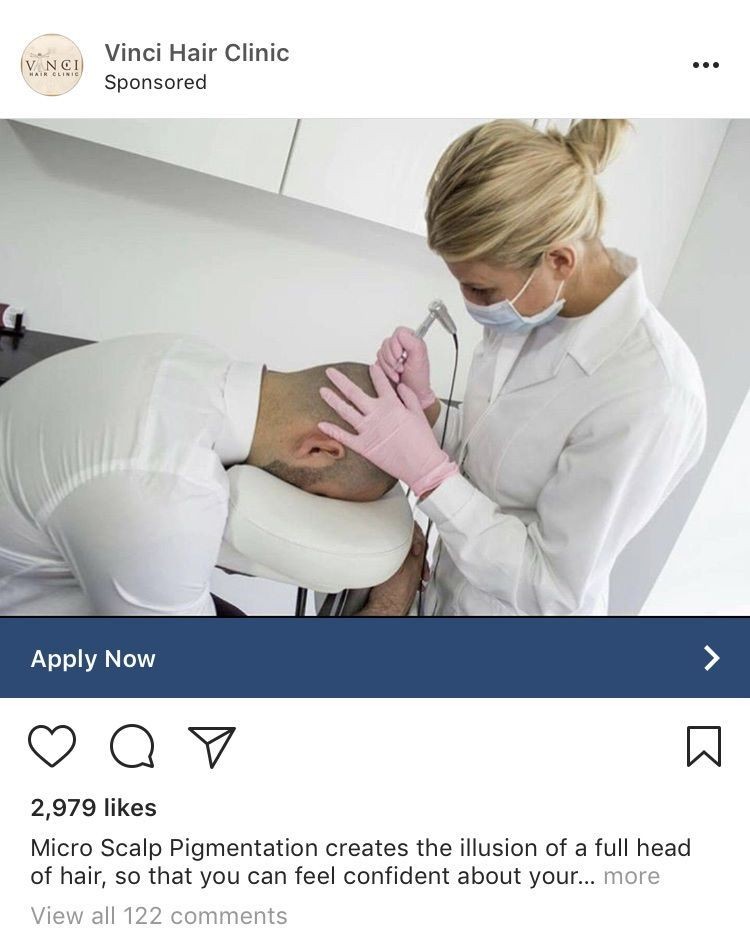

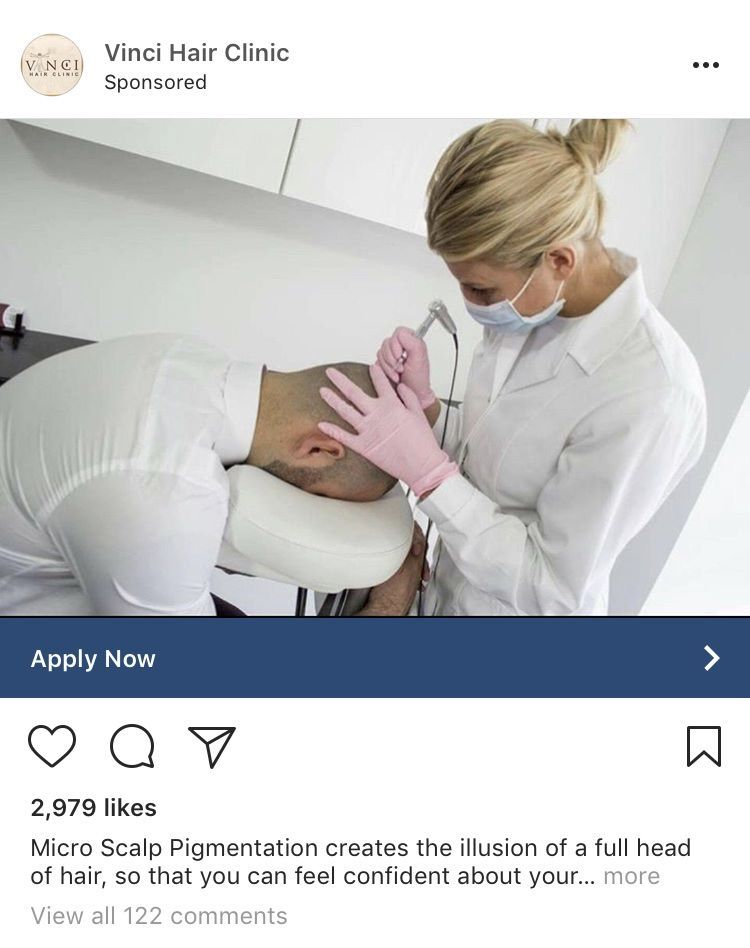

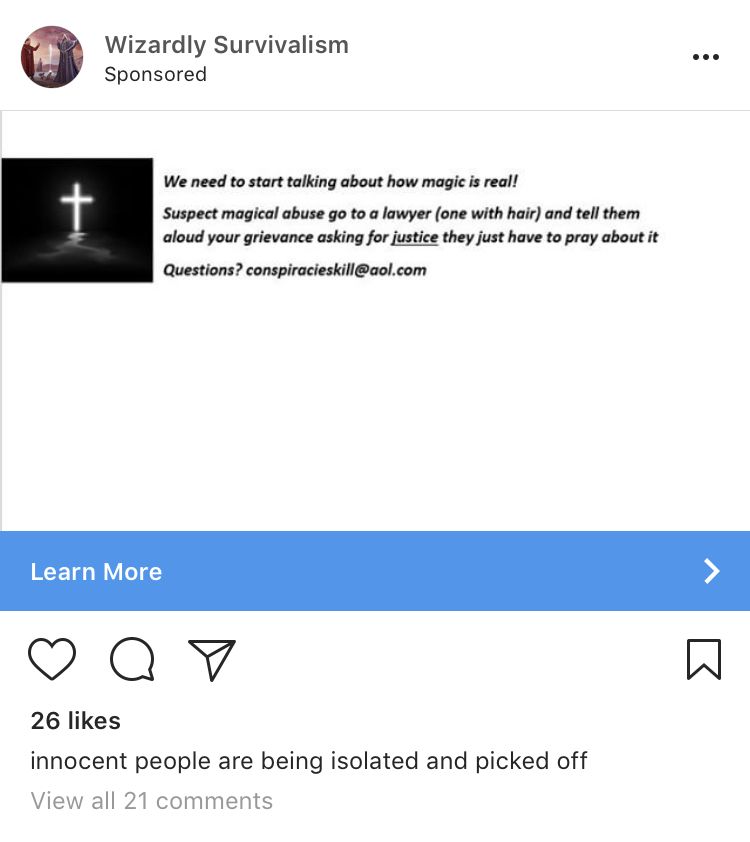

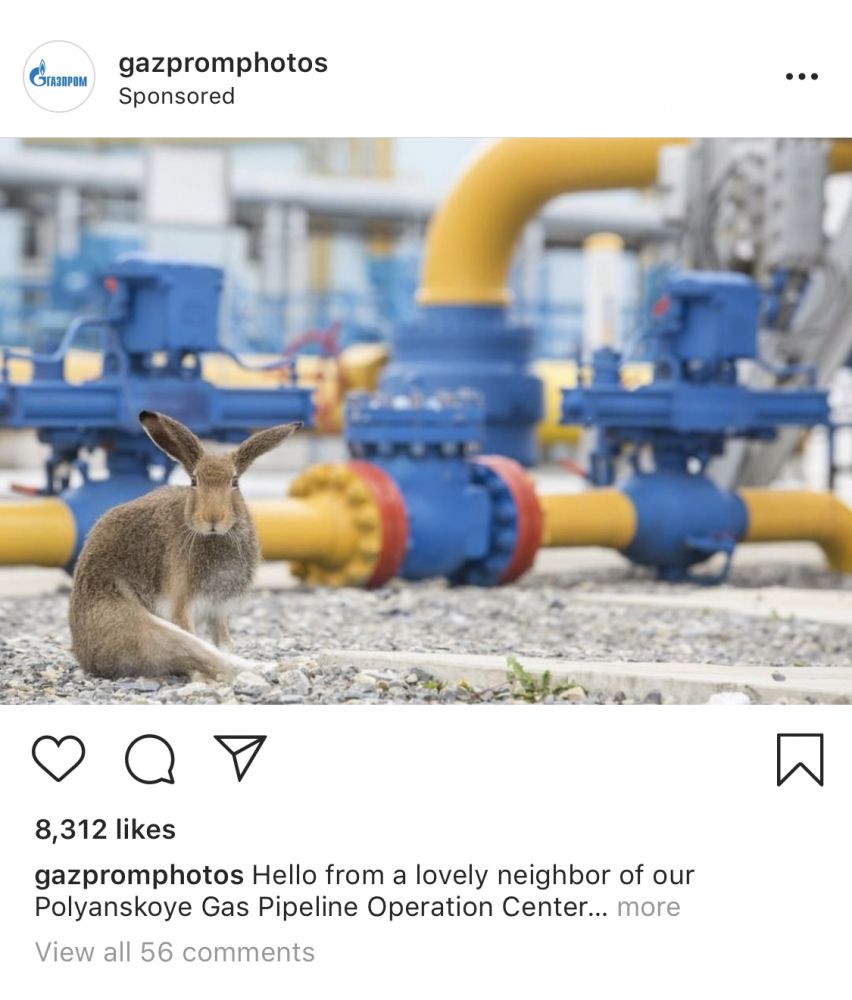

Even though I was no longer living in Brussels when Instagram introduced ads in 2013, my metadata thought I was. I was served ads in both Flemish and French for everything from Brussels drag queen performers to the Antwerp police department to Chernobyl tourism packages. They were simultaneously puzzling and marvelous: the juxtaposition of the keywords was completely surreal. I derived a certain perverse pleasure in the randomness.

-

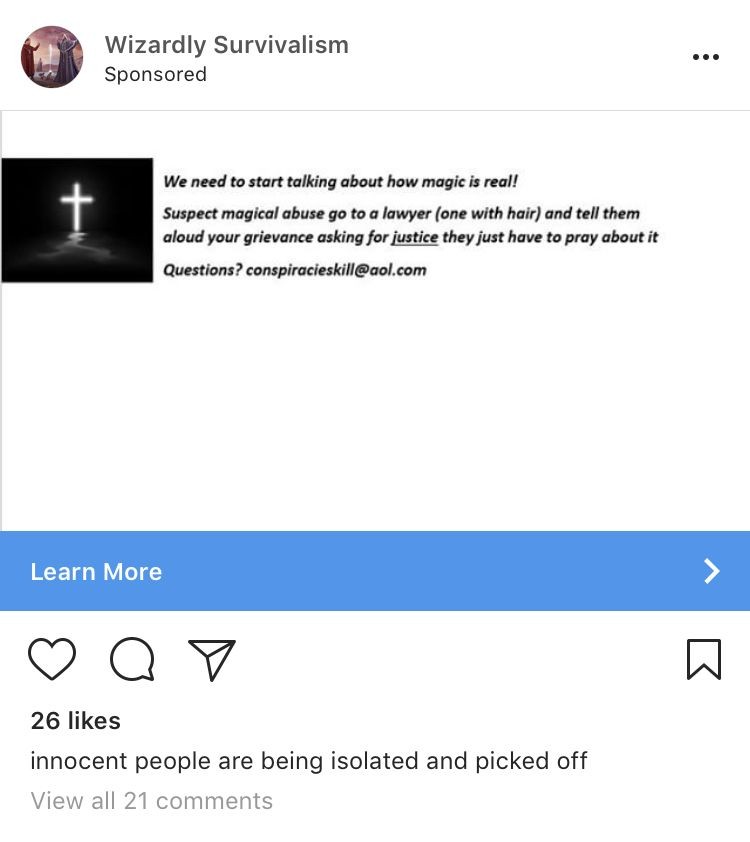

An example of the surreal ads Instagram was promoting on the author’s feed.

-

An example of the surreal ads Instagram was promoting on the author’s feed.

-

An example of the surreal ads Instagram was promoting on the author’s feed.

-

An example of the surreal ads Instagram was promoting on the author’s feed.

-

An example of the surreal ads Instagram was promoting on the author’s feed.

But I must admit something else; I had fed the algorithm noise, by clicking on the “hide” button for every single ad that appeared. For months on end, without fail, it became like a Pavlovian reaction. I would report ads for inappropriate content, or for spam, but never because it wasn’t relevant to me. I wanted the algorithm to think that my curiosity had no bounds, that everything was relevant to me, that I could not be marketed to. Marking them as spam or inappropriate wasn’t a lie; they were inappropriate spam, and this was my only recourse within the terms and conditions set forth by the platform, which of course, I could only “choose” to accept.

Then something amazing happened: the ads just... disappeared. I had Instagram with no ads for quite a long time — well into 2018 — and it made the place enjoyable through some glitch in the matrix, a benevolent ghost in the machine. Of course, with the rise of influencer culture, the ads just became more cleverly disguised as sponsored posts.

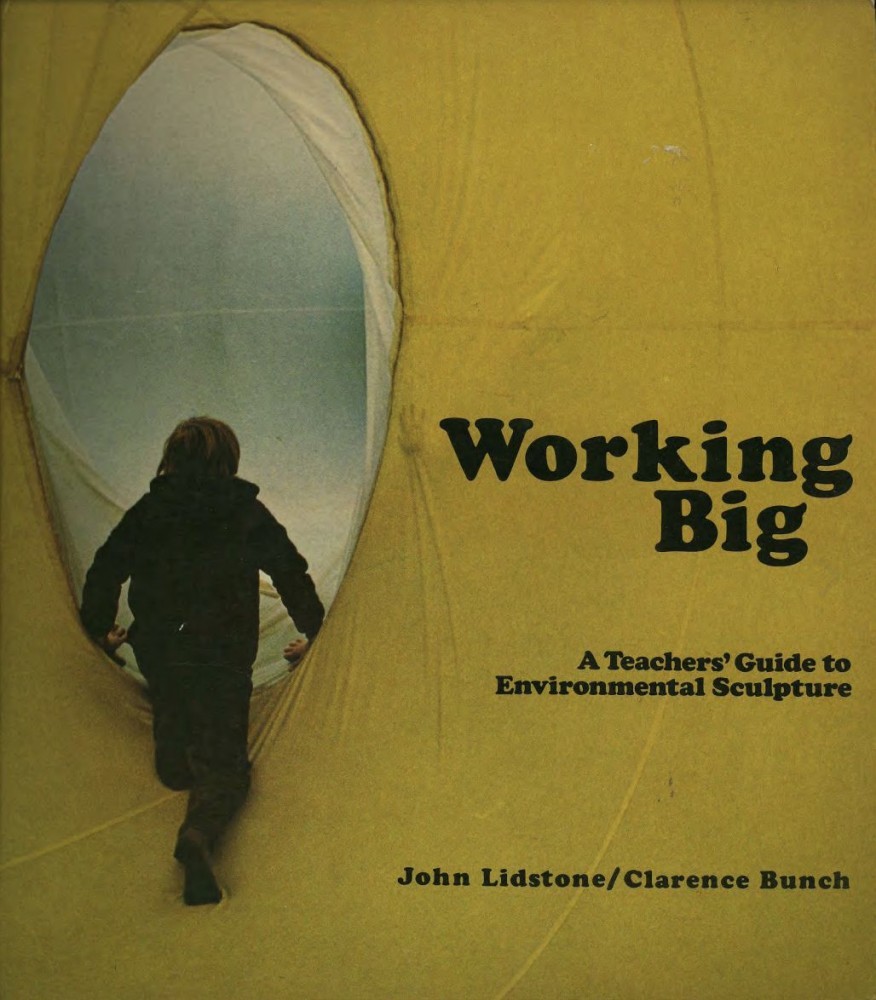

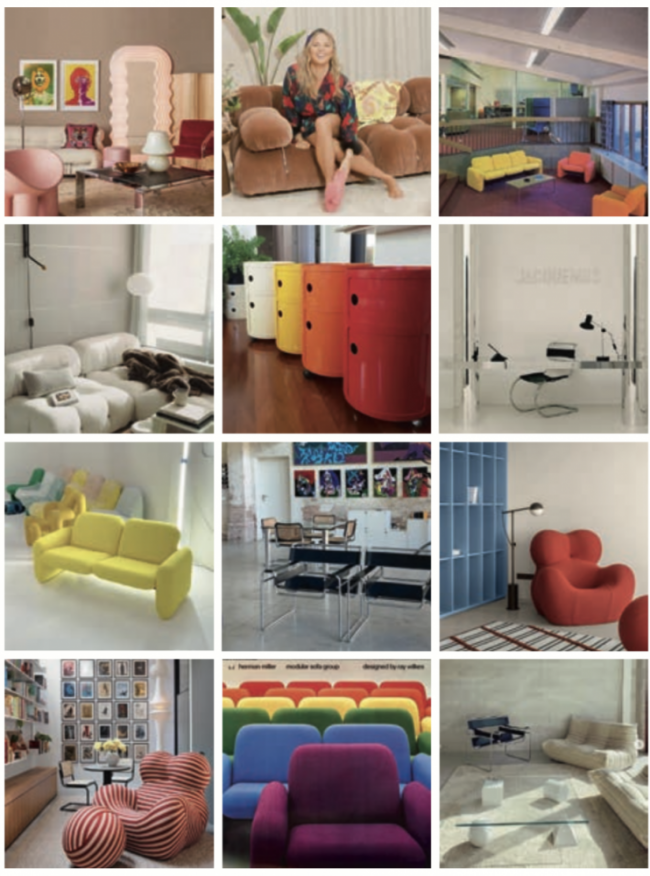

Without the algorithmic ads nudging me to be interested in things I wasn’t, or things it thought I would be and wasn’t, I spent my time in the app exploring subcultures; something I’d done on the world wide web since AOL in the 90s. Over the years I cycled through popular cultures like Blink 182, then more “underground” subcultures, from punk to ska to a mildly regrettable jam-band/Phish phase, then in the mid-2000s: architecture. As a subculture particularly adept at representation and the promotion of ego, architecture seemed a natural fit for Instagram’s vanity-driven business model. But by the early-2010s, nearly a decade later, I was finding myself becoming increasingly disillusioned with mainstream architecture culture. Too deep at that point to completely disavow architecture, I buried myself in niches like utopian 60s idealism (Ant Farm), space frames, b-sides (thanks to my studio neighbor who ran a then-tiny tumblr account Archive of Affinities), and inflatable structures. The latter became such an obsession that my graduate thesis in architecture school was a giant inflatable, and then I became known as “bubble boy.”

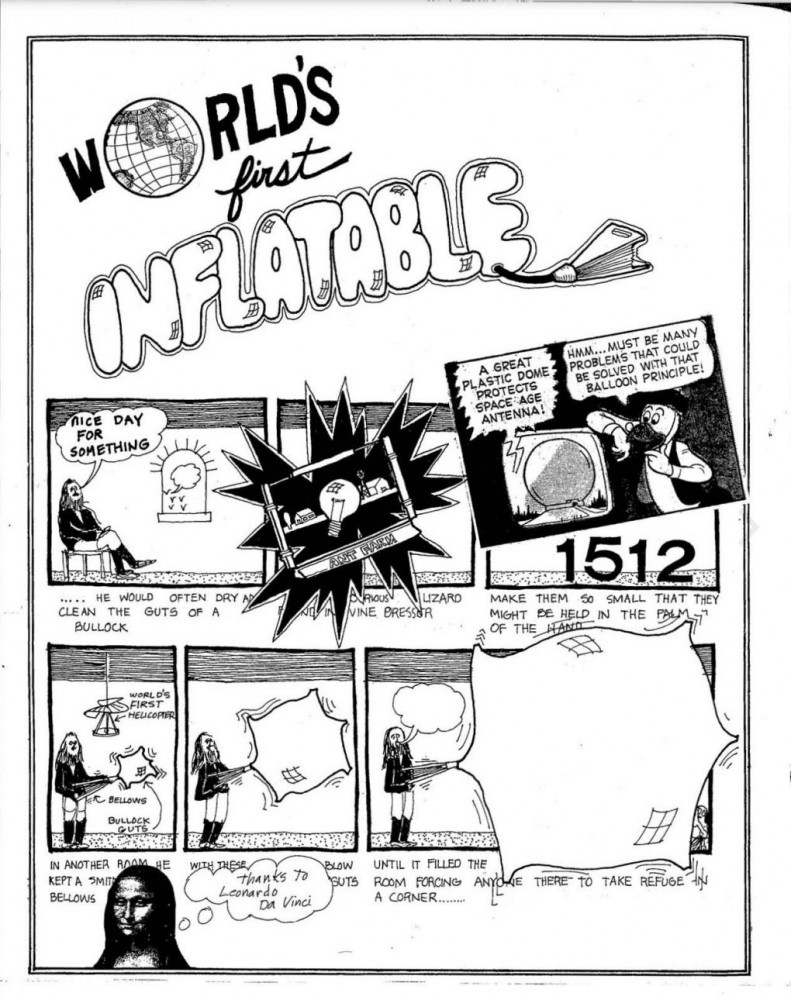

Comic from Ant Farm’s Inflatocookbook (1971).

Inflatables (& Instagram)

Employing Keller Easterling’s formulation of “spatial protocols,” I developed a pneumatic spatial protocol examining inflatables — designing, simulating, fabricating, and producing these structures for special events, mainly music and dance performances, art events, and branded pop-ups. The potentials were many, but at the same time limited. You wouldn’t make an inflatable office space or a permanent home. The fact that I could execute these projects mostly by myself was liberatory but also lonely. I sought out a community that I knew existed online, and specifically on Instagram, to feel a bit less alone.

I trawled the depths of the hashtag abyss, following everything from NFPA701 to inflatable dolls, to rural Catalan and Chinese tensile membrane engineering firms. It was a diverse, and weird, assortment that I could only find on Instagram. I talked and shared resources with others who were designing and creating inflatable structures in places including Buenos Aires, Tunisia, Mexico, rural France, Seattle, and Providence, and with my editorial and publishing experience, schemed an idea for an update to Ant Farm’s 1971 Inflatocookbook to include all their work. My interest in using the architectural education I had received in service of direct action, controlling the means of production through inventing self-fabrication techniques, affordable vernacular materials, and the spatial politics and potentials of temporary structures for communities and situations typically forgotten and erased by the architectural discipline were mirrored by the communication dynamics on the platform.

Performa Environment Bubble

For Performa 17, I was invited to consult on the realization of François Dallegret’s 1965 unbuilt design for The Environment-Bubble, which was realized in collaboration with late architect François Perrin and choreographer Dimitri Chamblas, turning the inflatable structure into an active site of intellectual and physical engagement with free daily dance workshops. Until it was successfully installed, Performa’s founding director and chief curator Roselee Goldberg had many doubts regarding The Environment-Bubble. But it became an instagrammable moment for the biennial, and eventually their website’s front-page image. It helped that it was in photogenic locations: Brooklyn Bridge park where every tourist takes their iconic New York photo backdropped by Brooklyn Bridge and the Manhattan skyline, as well as in Central Park with the under-construction pencil-thin skyscrapers of Billionaires’ Row around 57th Street in the background. Everyone from joggers to newlyweds stopped and wanted to have their photo taken either inside or in front of the structure.

-

A couple takes their wedding photos inside The Environment-Bubble installed as part of Performa 17 in DUMBO, November 2017. Photography by Jesse Seegers.

-

A couple takes their wedding photos inside The Environment-Bubble installed as part of Performa 17 in DUMBO, November 2017. Photography by Jesse Seegers.

-

A couple takes their wedding photos inside The Environment-Bubble installed as part of Performa 17 in DUMBO, November 2017. Photography by Jesse Seegers.

-

A couple takes their wedding photos inside The Environment-Bubble installed as part of Performa 17 in DUMBO, November 2017. Photography by Jesse Seegers.

-

A couple takes their wedding photos inside The Environment-Bubble installed as part of Performa 17 in DUMBO, November 2017. Photography by Jesse Seegers.

-

A couple takes their wedding photos inside The Environment-Bubble installed as part of Performa 17 in DUMBO, November 2017. Photography by Jesse Seegers.

-

A couple takes their wedding photos inside The Environment-Bubble installed as part of Performa 17 in DUMBO, November 2017. Photography by Jesse Seegers.

-

A couple takes their wedding photos inside The Environment-Bubble installed as part of Performa 17 in DUMBO, November 2017. Photography by Jesse Seegers.

-

A couple takes their wedding photos inside The Environment-Bubble installed as part of Performa 17 in DUMBO, November 2017. Photography by Jesse Seegers.

-

A couple takes their wedding photos inside The Environment-Bubble installed as part of Performa 17 in DUMBO, November 2017. Photography by Jesse Seegers.

-

A couple takes their wedding photos inside The Environment-Bubble installed as part of Performa 17 in DUMBO, November 2017. Photography by Jesse Seegers.

I even wrote an essay for the (still unreleased, *shrug*) Performa 17 catalogue about how the recent proliferation of and interest in inflatable structures can be traced back to the social and political dynamics of their origin in the 60s and 70s, when the new technology was plastic not social media. Inflatable structures are a productive metaphor for social media: both are ephemeral, photogenic or fueled by content that is, and have the potential to trigger a coalescing of friends and strangers alike, where once you enter the space, you can’t hear what’s happening outside, just the ambient white noise of the fan, holding the entire structure up.

-

Author Jesse Seegers was the inflatable architecture consultant for The Environment-Bubble, an artwork by François Dallegret, in collaboration with Francois Perrin and Dimitri Chamblas, realized for Performa 17, documented here on Seegers’s instagram.

-

Author Jesse Seegers was the inflatable architecture consultant for The Environment-Bubble, an artwork by François Dallegret, in collaboration with Francois Perrin and Dimitri Chamblas, realized for Performa 17, documented here on Seegers’s instagram.

-

Author Jesse Seegers was the inflatable architecture consultant for The Environment-Bubble, an artwork by François Dallegret, in collaboration with Francois Perrin and Dimitri Chamblas, realized for Performa 17, documented here on Seegers’s instagram.

-

Author Jesse Seegers was the inflatable architecture consultant for The Environment-Bubble, an artwork by François Dallegret, in collaboration with Francois Perrin and Dimitri Chamblas, realized for Performa 17, documented here on Seegers’s instagram.

-

Author Jesse Seegers was the inflatable architecture consultant for The Environment-Bubble, an artwork by François Dallegret, in collaboration with Francois Perrin and Dimitri Chamblas, realized for Performa 17, documented here on Seegers’s instagram.

But in the case of The Environment-Bubble for Performa, once inside, interactions were full of potential that was not possible outside the bubble, out in the open. Another thing happened: people on the outside could still see in, but the people inside, in a literal echo chamber, could not see out, and they didn’t seem to care that they were being watched, surveilled, recorded (literally, in photos and on video). Everyone was enjoying the spectacle, even — or especially — the ones inside who were the spectacle. People on the outside wanted to know what it was like inside — they would poke their heads in, and see people beautifully lit in diffuse light, children running around (they were inside a crazy almost-bouncy castle, after all), and then want to rush in to join them.

A similar rush happened with social media. All of a sudden every business had a “like us on Facebook” or “follow us on Instagram” branding graphic next to their name, menu, website header, you name it. Everybody wanted to see what it was like inside.

We thought this was great, at the time.

But then the magic wore off and faded into something resembling depression. The scroll lost that pleasurable thrill and turned into an obligation to self-brand, to commodify oneself into images, then videos. The app became a panopticon we voluntarily subjected ourselves to, just like the inflatable people chose to enter, not worried that they were being surveilled and turned into commodified images once inside.

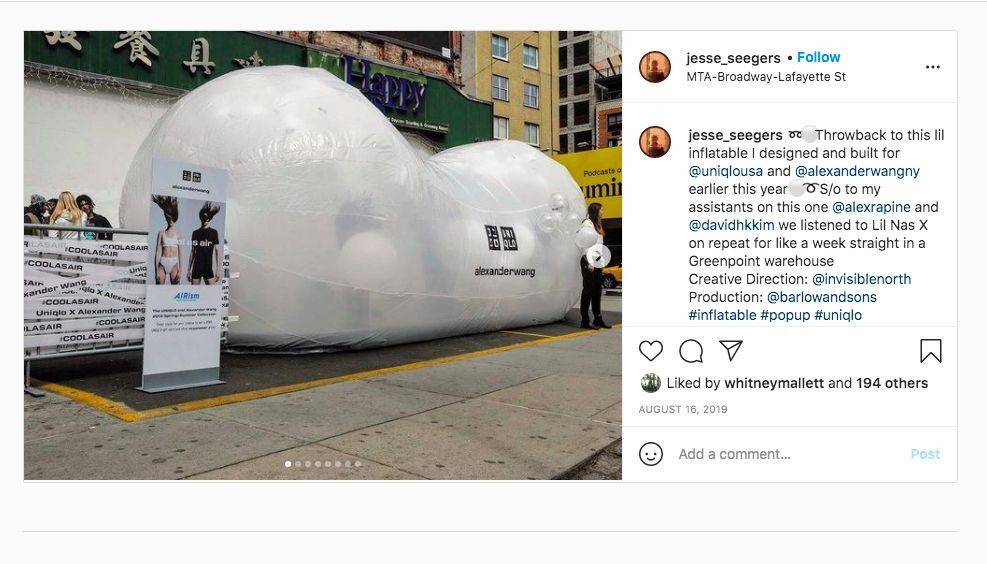

An inflatable that author Jesse Seegers designed for a Uniqlo and Alexander Wang pop-up event in 2019.

The magic wore off designing inflatables too. Sure, I did some “cool” branded pop-ups, which paid much better than the actually cool cultural projects for musicians and performances, but the bankruptcy, whether financial or moral, persisted in both spheres. Uniqlo and Alexander Wang corporate didn’t care about spatial liberation or allowing young people to realize that they can have agency in their immediate environment. These corporations only cared about quarterly earnings. I get it, capitalism is the sea we swim in — we all (myself included) have to pay rent, and food can’t be bought with exposure (maybe Bourdieu would disagree).

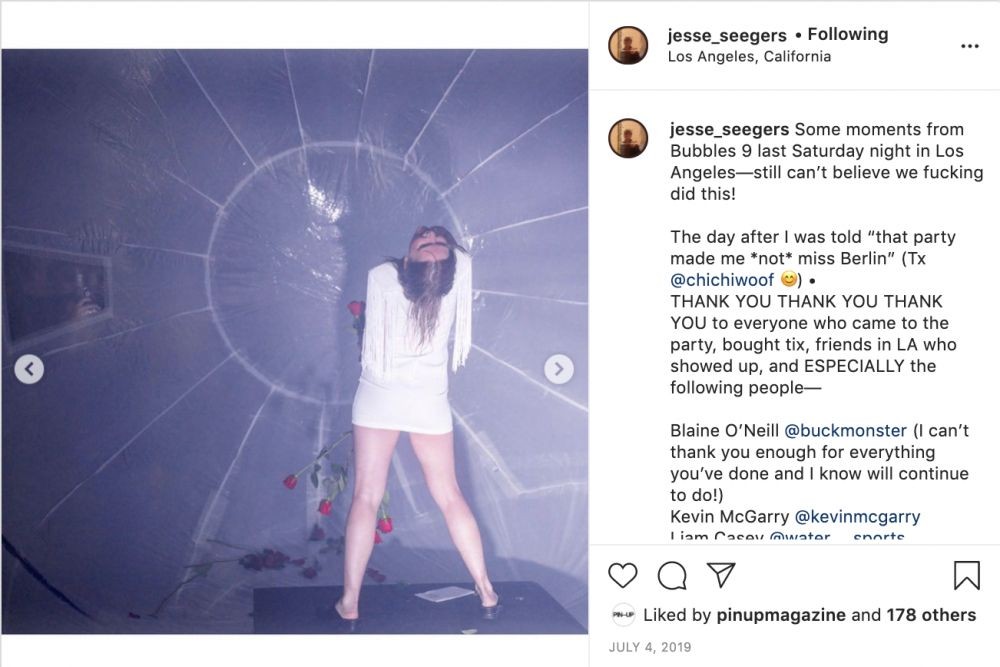

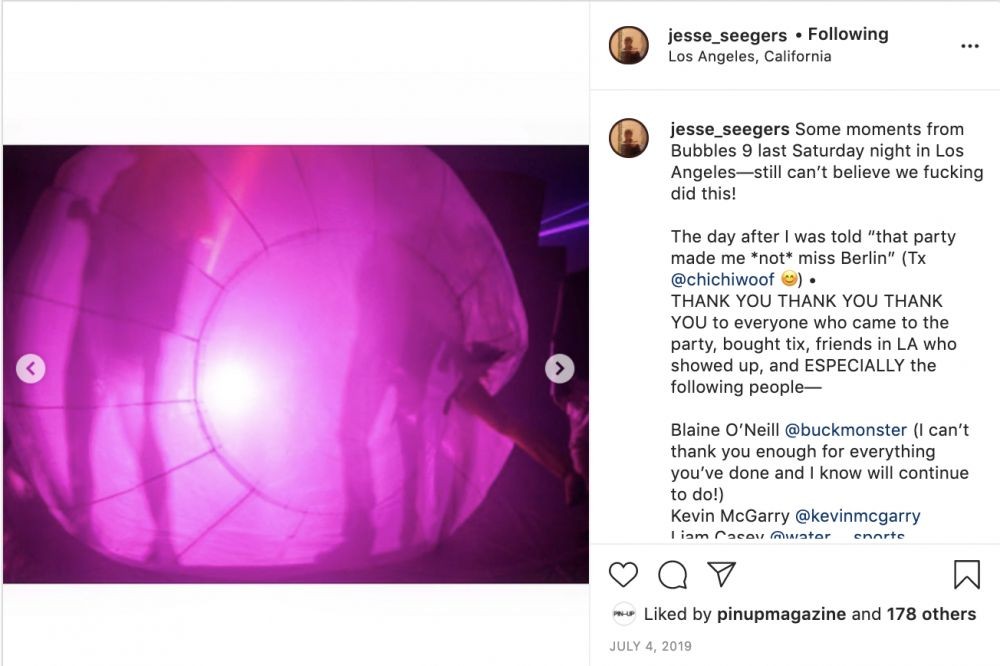

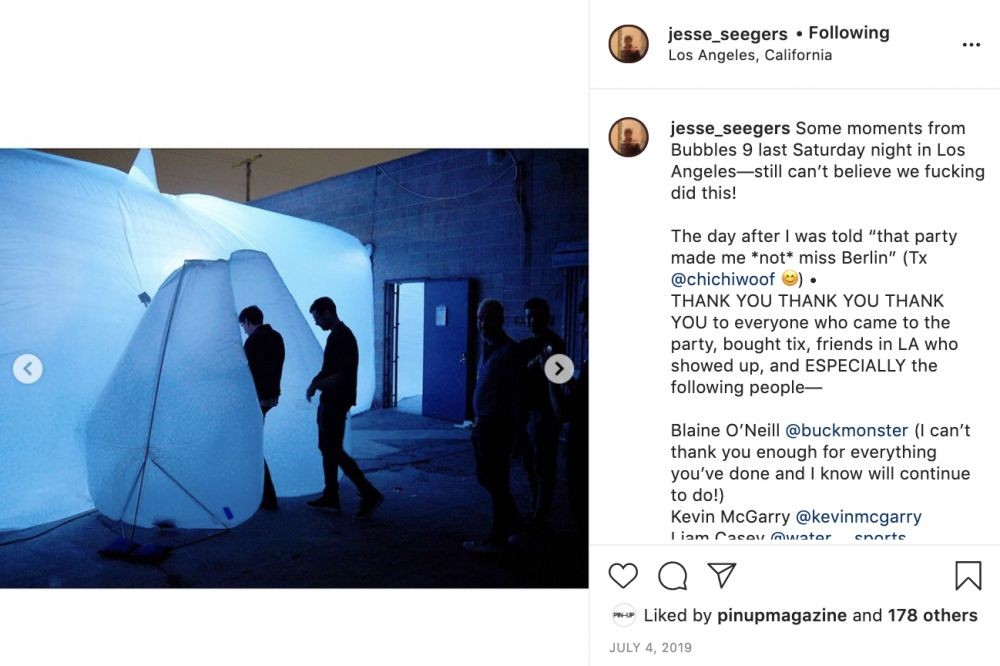

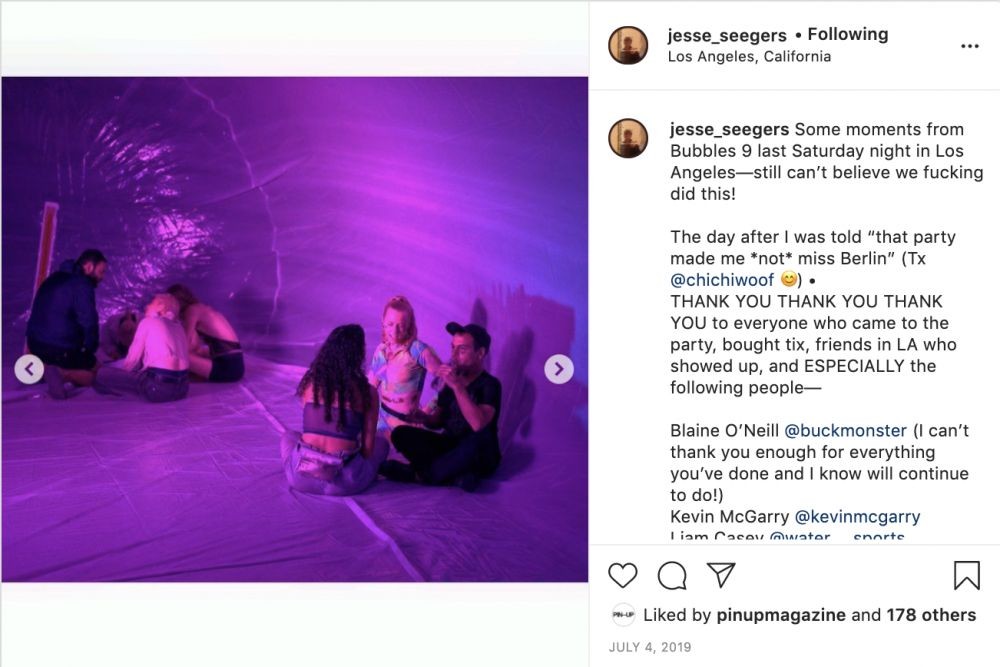

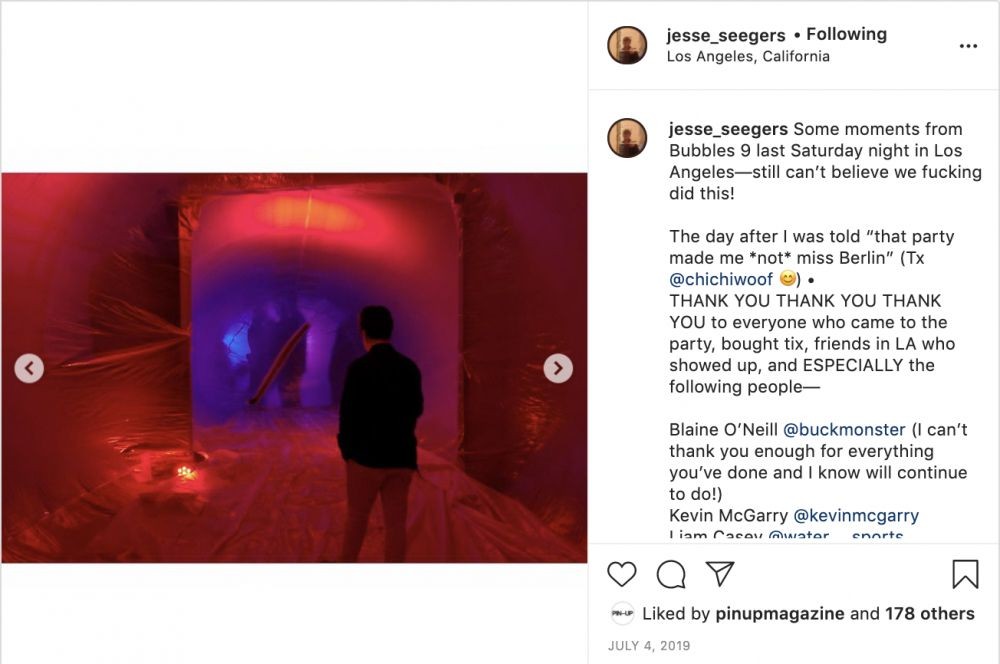

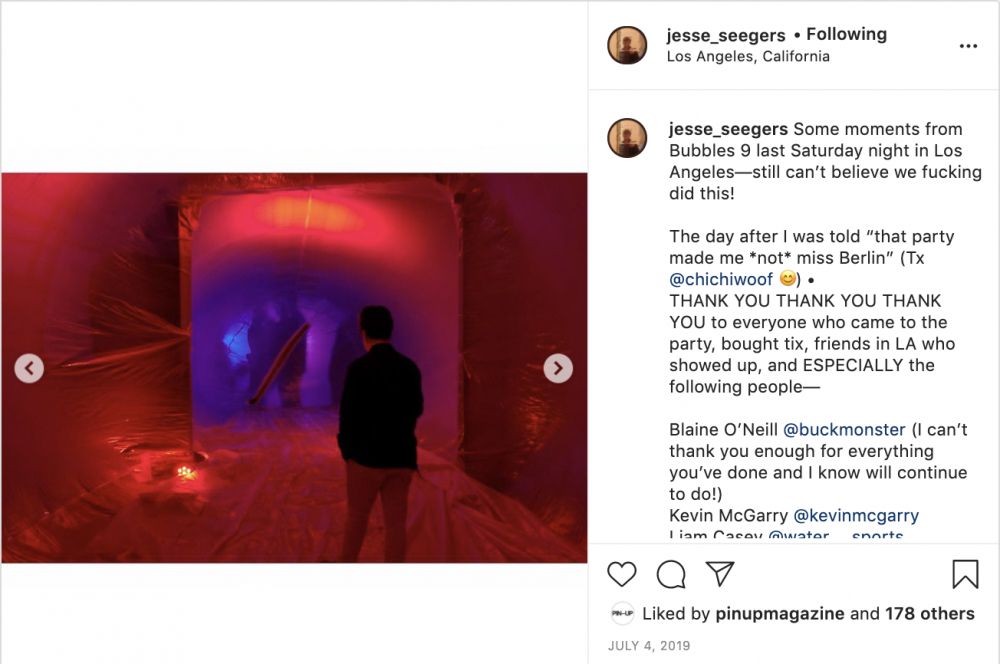

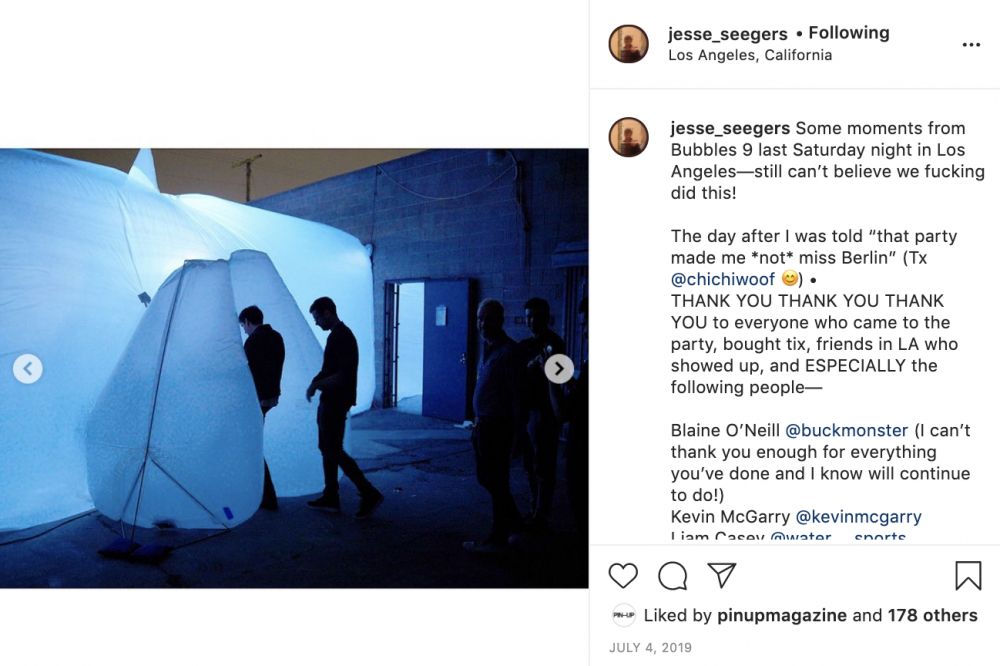

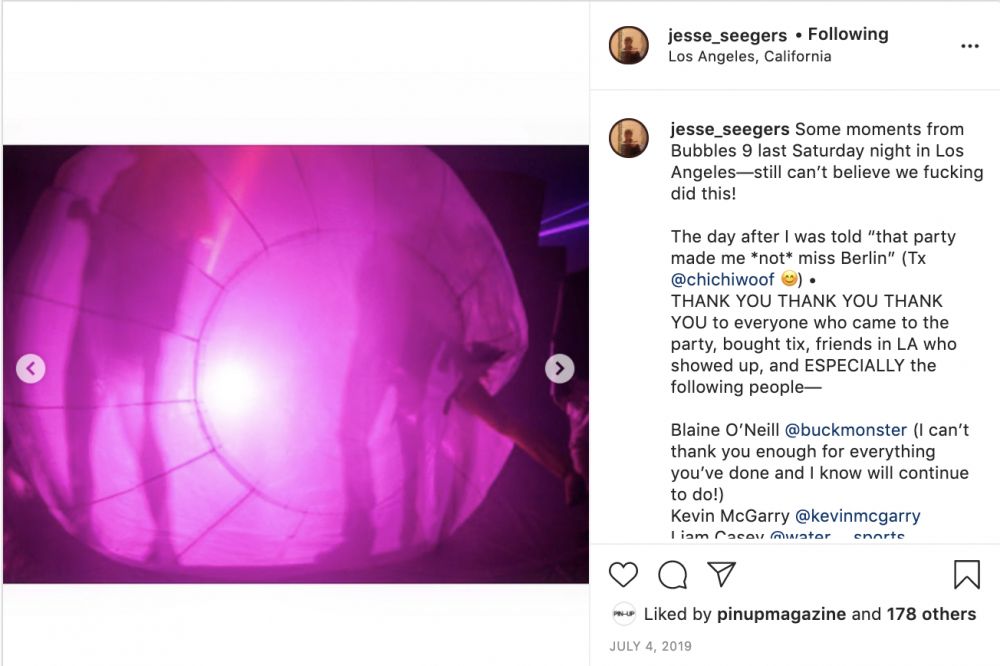

Still I was able sneak my own agenda into each of these projects, testing formal variations within the pneumatic spatial protocol. Defined by site constraints, fabrication lead times, and production budgets, but ultimately able to be realized with several simple tools and a few assistants who I really enjoyed hanging out with, each project was both exhausting and invigorating, mentally and physically. While I was able to use my dividends, the detritus of capitalism, for my own ends, for queer raves and music performances benefiting local art and immigrant communities — like Bubbles 9 in L.A. last summer — in the end I just couldn’t hustle to the extent required to make these corporate projects happen on the budgets they made available. I told myself I would only do inflatables if the client was aligned with the larger mission of the pneumatic spatial protocol, even if they themselves weren’t aware of it.

-

Inflatables that author Jesse Seegers built for Bubbles 9, a rave in downtown Los Angeles. Photography by Injee Unshin.

-

Inflatables that author Jesse Seegers built for Bubbles 9, a rave in downtown Los Angeles. Photography by Injee Unshin.

-

Inflatables that author Jesse Seegers built for Bubbles 9, a rave in downtown Los Angeles. Photography by Injee Unshin.

-

Inflatables that author Jesse Seegers built for Bubbles 9, a rave in downtown Los Angeles. Photography by Injee Unshin.

-

Inflatables that author Jesse Seegers built for Bubbles 9, a rave in downtown Los Angeles. Photography by Injee Unshin.

-

Inflatables that author Jesse Seegers built for Bubbles 9, a rave in downtown Los Angeles. Photography by Injee Unshin.

New Museum Ideas City Conversation Cloud

In the summer of 2019 I was invited to make an inflatable conversation space for the New Museum IdeasCity festival which was to take place in the Bronx. Having heard not-great anecdotes about the museum’s labor practices and stiffing contractors in the past, my initial reticence was overcome by the lure of exposure: plus the site was going to be a barge, right next to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s district, and she would be the keynote speaker!

When the New Museum informed me that they could only pay me one-tenth of the production costs, IdeasCity curator Mitch McEwen cleverly leveraged my alumni status at Princeton, where she teaches, to pick up some of the budget and production slack. I got to revisit the campus, conduct a workshop with undergraduates, and we finished building and inflated the structure together at the school’s Embodied Computation Lab. That was the successful part of the project.

The inflatable designed by author Jesse Seegers for the canceled New Museum IdeasCity Bronx in the Concrete Plant Park, September 2019.

The failure came as a result of New Museum’s poor management and miscommunication with local communities, which was all revealed to me, along with the rest of the festival participants, on the day of the event, as I was installing at 7 a.m. in the Concrete Plant Park. The museum’s attempt to import and commodify its cultural capital under the guise of building a new community where many already existed couldn’t be ignored any longer. Organizers interrupted the event’s opening remarks, and alleged (and given the crowd it seemed a fair point) that none of the people who’d come to the park for the event would ever venture to the Bronx again except for a Yankees game. The day-long event was then canceled, and in that moment, the inflatable space shifted from a space for conversation to a space for mourning and catharsis, offering an almost Edenic calm in the middle of a sea of gentrifier-induced hostility. The inflatable still worked, though not for its intended use. The speakers who were going to speak inside had all rescinded their participation in solidarity with the local community.

This experience is a metaphor for the liberal bubble most of the art and architecture world resides in — so blinded by privilege and obsessed with prestige that our whiteness and capital becomes systemically offensive without us ever realizing it or considering why. That is, until this quieter systemic white supremacy and casual economic violence can no longer be tolerated, and the situation erupts in righteous, justified, catharsis.

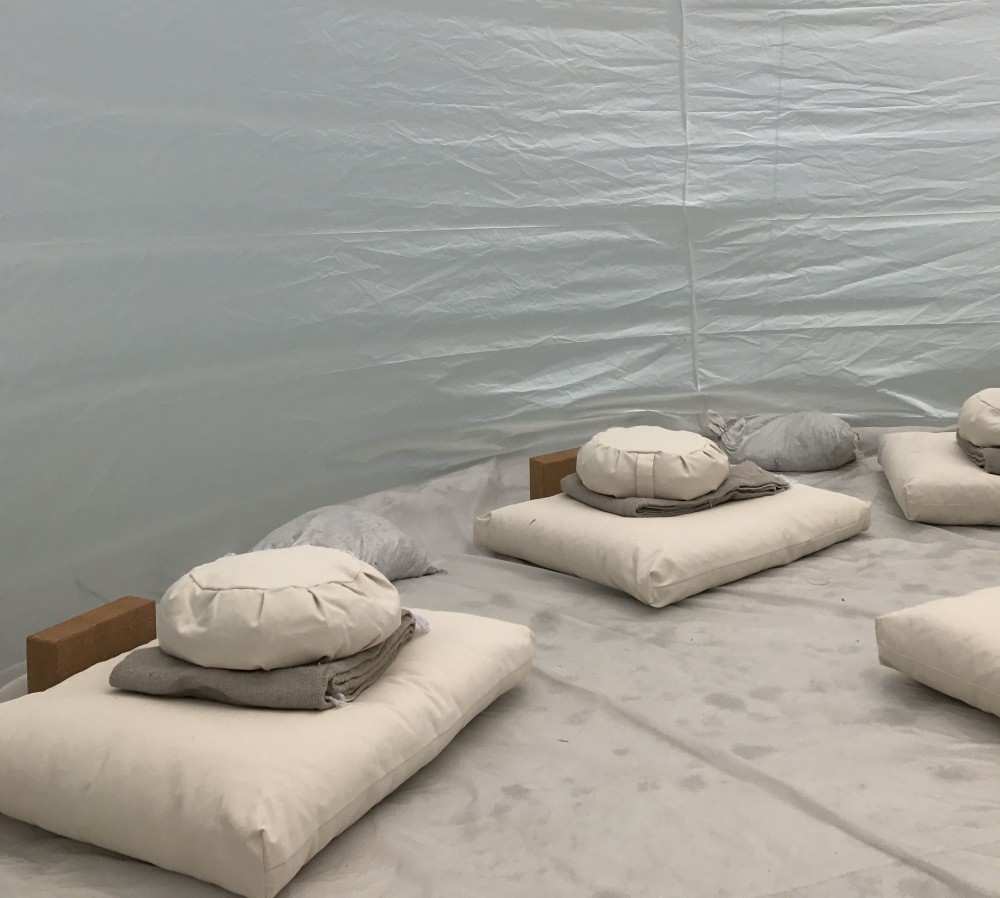

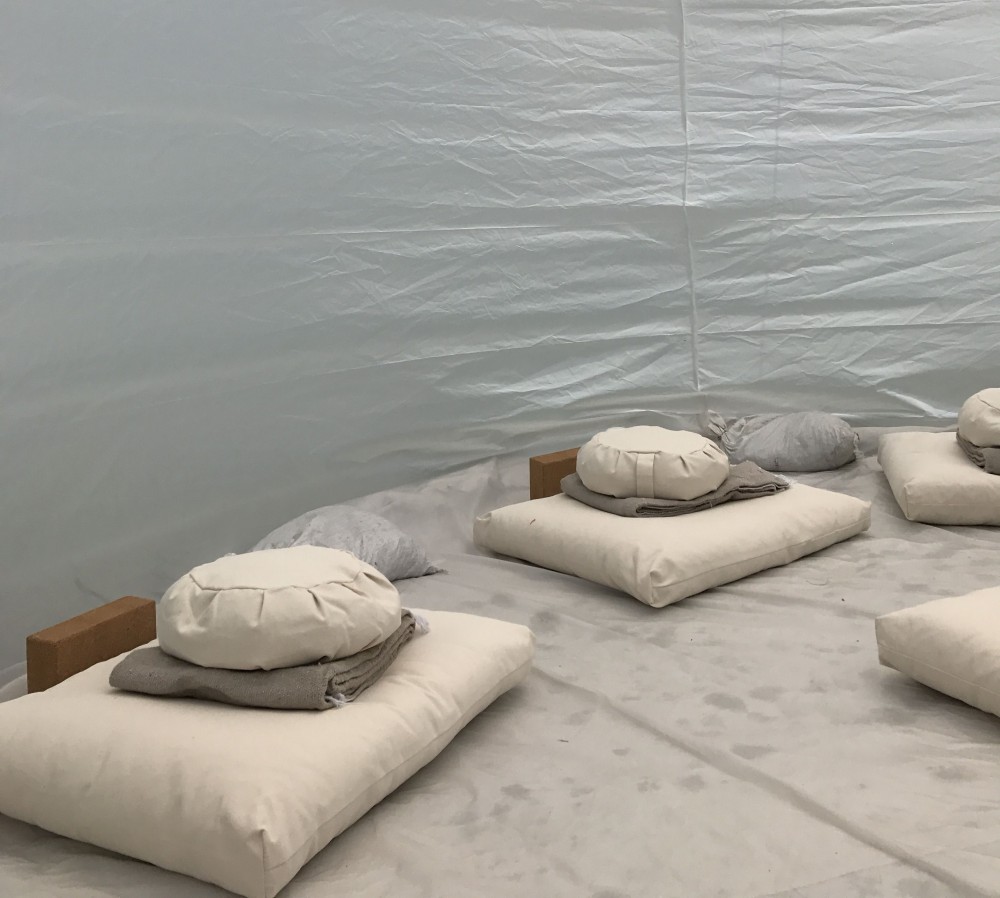

Inside the Yoga Dome designed by author Jesse Seegers in 2017.

I myself was in that liberal bubble as well, but after I packed up that inflatable, I could not in good conscience continue to pretend to be outside of or silent about how neoliberal corporations (including art museums), inflict institutional harm on their audience, no matter how “well-intentioned.”

This past spring and summer, racial justice protests in the memory of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and too many others brought to the fore many of the toxic dynamics on Instagram and other attention-economy-oriented social media platforms, including but not limited to white people posting black squares as if that meant solidarity or direct action. The tech optimism of the 2010s was over. There finally seemed a collective realization that Instagram was dead and now is the time for us to build new institutions and digital networks, ones that increase access and inclusivity.

So the next time you open Instagram, make no mistake at what you’re seeing: a squeaky clean façade of a zombie culture. Its simulacra of a cultural landscape will live on as long as you feed it your attention, but its potential for meaningful subcultural community building is long past dead.

-

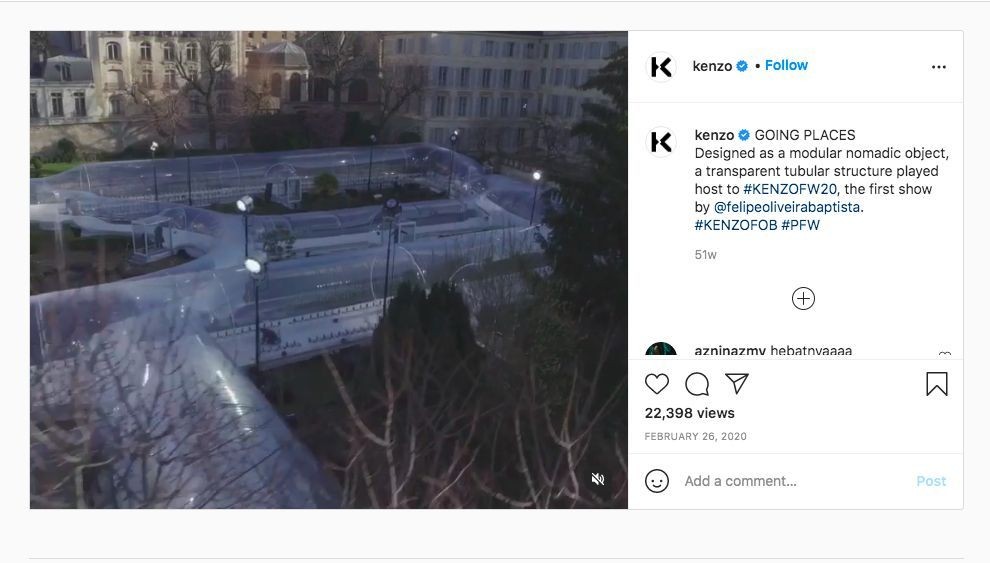

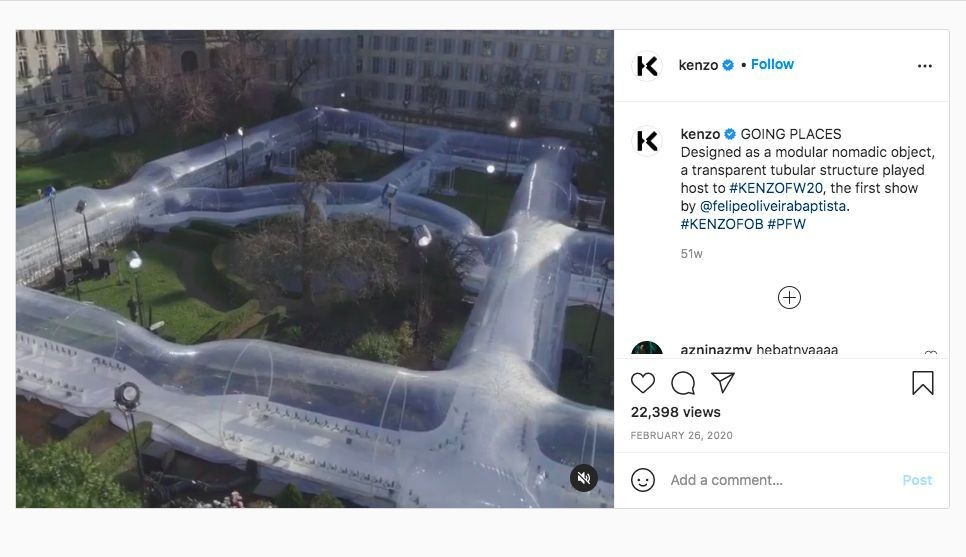

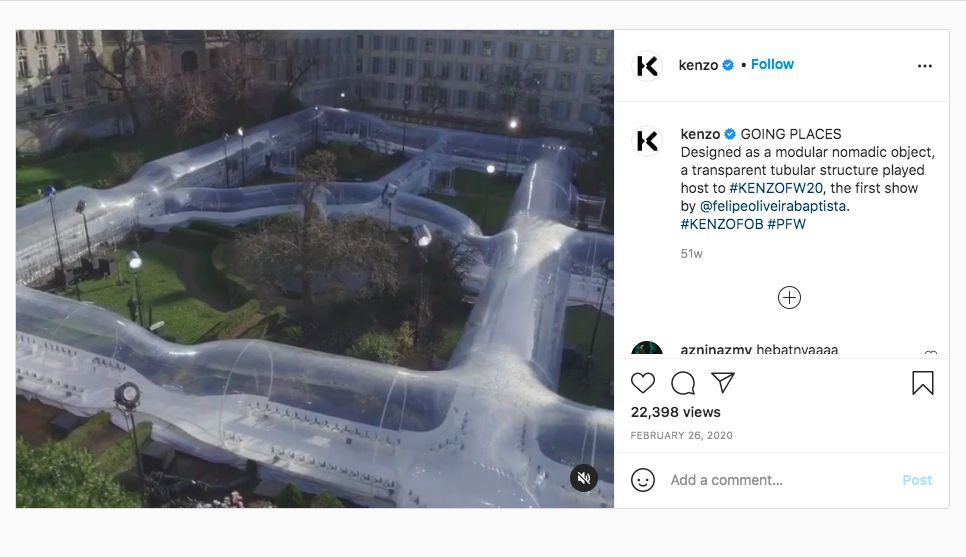

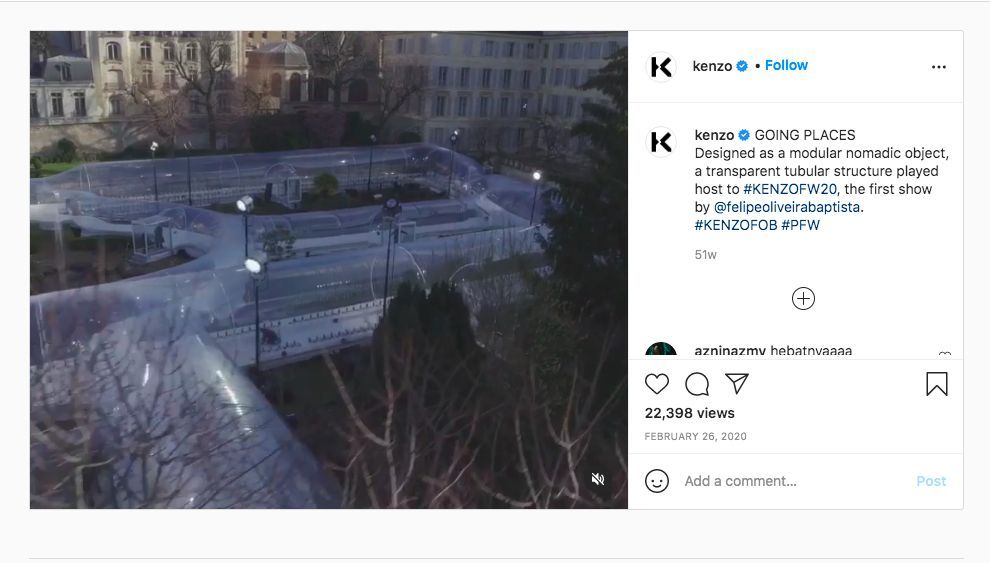

An inflatable made for Kenzo’s Fall Winter 2020 Paris presentation, as seen on Instagram.

-

An inflatable made for Kenzo’s Fall Winter 2020 Paris presentation, as seen on Instagram.

Disembodied drone footage of the inflatable made for Kenzo’s F/W20 Paris presentation is the apex of this specific deployment of the pneumatic spatial protocol: the manufacturing of desire through spectacle. Only once you resolutely step outside — the inflatable or the app — can you see this shiny bubble for what it really is: not only a void of meaningful social connection, but perhaps antithetical to it.

It won’t go away, of course. Instagram, thanks to FACEBOOK, will just further devour other apps (perhaps Clubhouse or Discord are next) attaching shopping-cart buttons to every cultural landscape it colonizes. It will continue as a less-and-less populated shopping mall of manufactured millennial desire.

But hey, zombie movies are surprisingly popular...