DATA RECOVERY: Digital Archiving And Obsolescence

In 2013, the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) presented Archaeology of the Digital, an exhibition by Greg Lynn spotlighting how emerging digital technologies had shaped architecture c. 1985–95 through projects by Peter Eisenman, Frank Gehry, Chuck Hoberman, and Shohei Yoh. While models, photos, and drawings survived intact, the original computer files had been lost for all but one project in the show — Gehry’s Lewis Residence. “The imminent danger of losing even more digital records compelled us to take a first step towards collecting this type of material,” then-CCA director Mirko Zardini wrote of the impetus behind the exhibition.

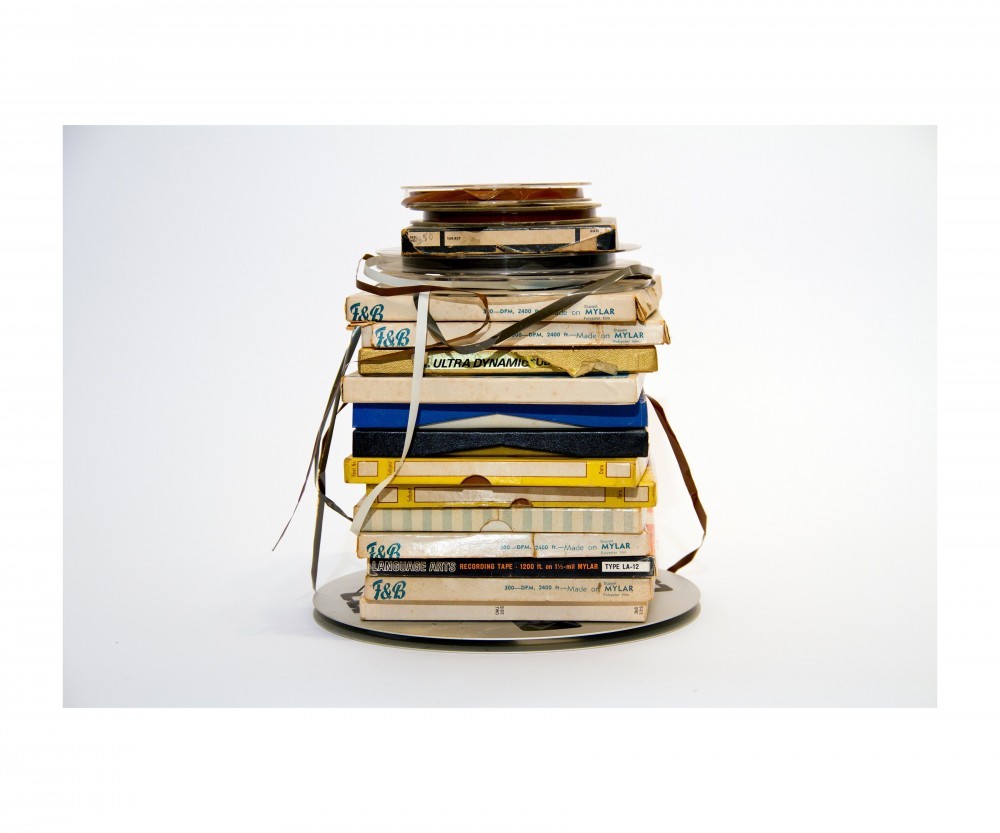

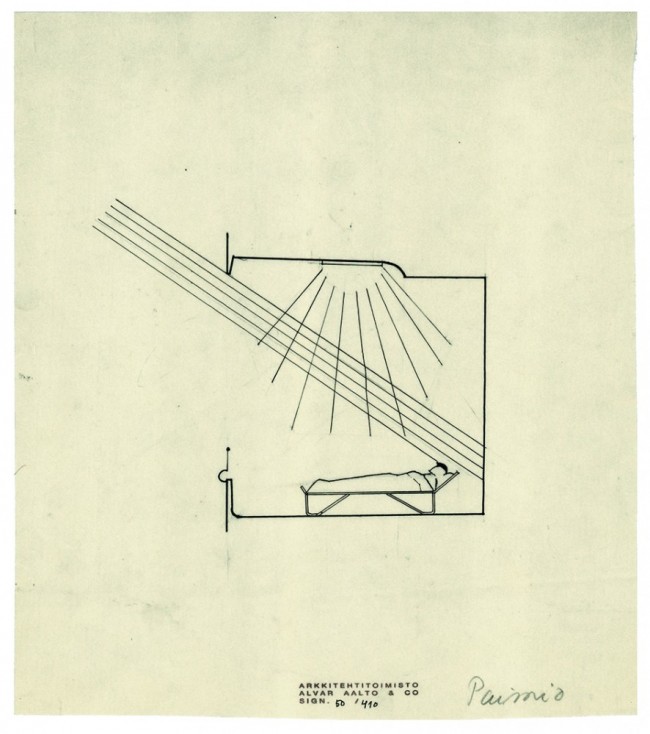

Julia Christensen, What Remains (Estate Sale 1) (2014) from the series Hard Copy.

While the abstraction of a digital file might seem timeless — whether a CAD drawing, the algorithm behind a building, a website, or a film — they’ve proven to be anything but. As Lynn put it in the exhibition’s catalogue, “The iterations of digital files, the native digital objects and data-sets, as well as the tools and machines used in their production are disappearing with every migration to a new operating system, every move of an office, and every upgrade in hardware.” Books and paper may seem outmoded, but when it comes to archiving, their readability lasts. The same can’t be said of digital tech. In the case of increasingly computerized architecture, where, in place of hand drawings, models, or blueprints, we have custom-developed programs, parametric models, and virtual-reality environments, the archive only seems to diminish as the amount of data grows. The U.K.-based Digital Preservation Coalition lists 3D engineering files as a “digitally endangered species,” a header that includes the output of CAD, BIM, and other architectural software.

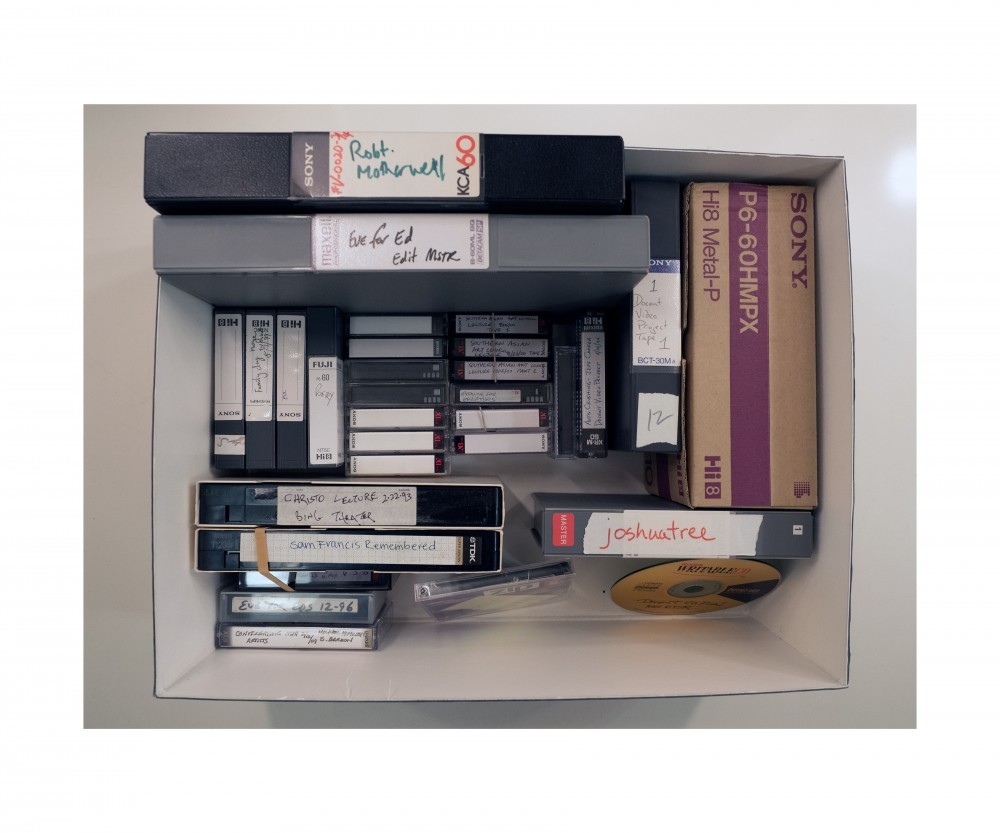

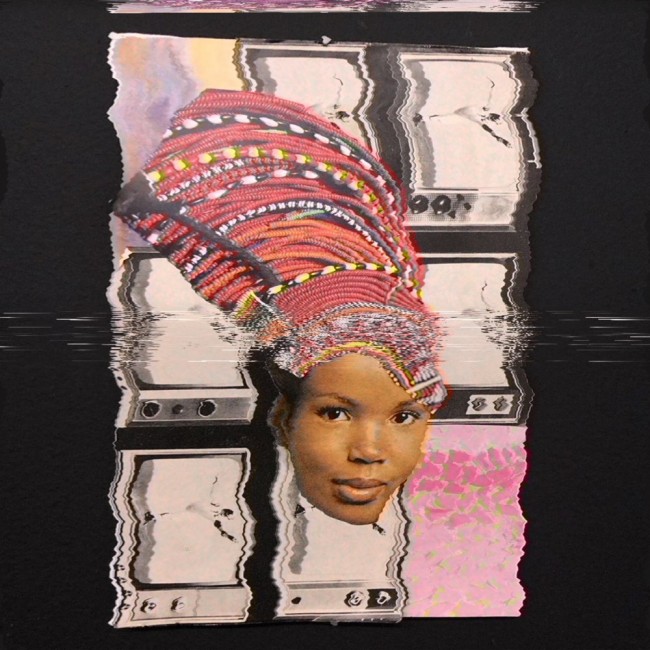

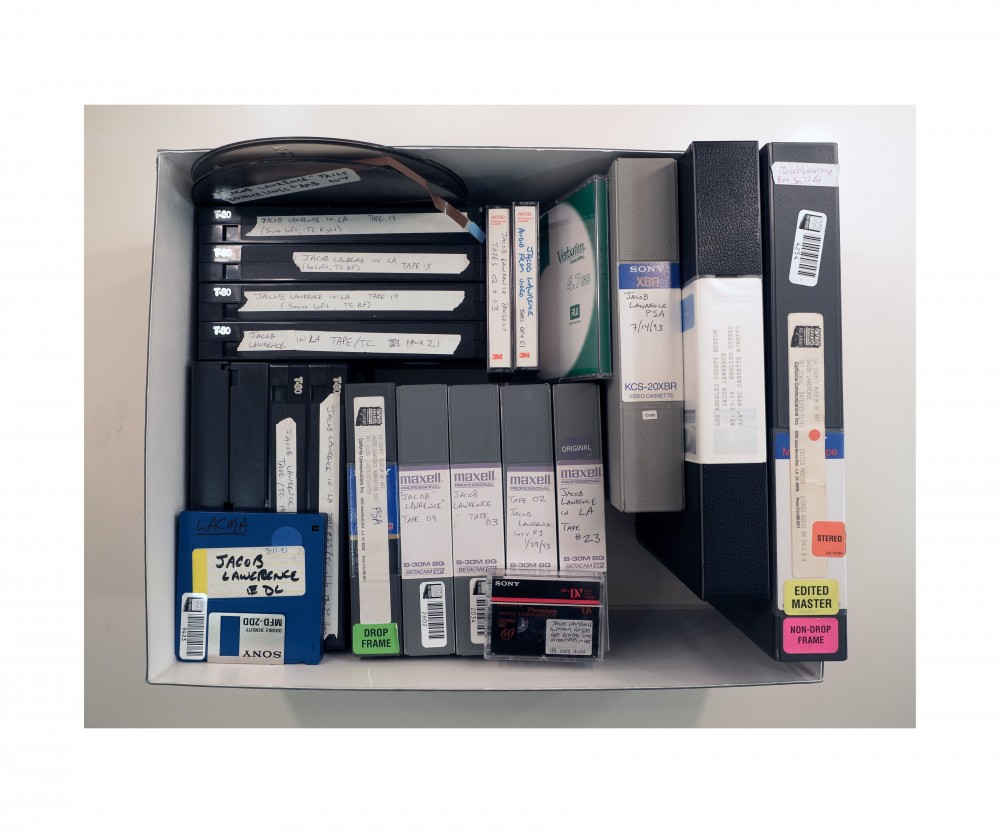

Julia Christensen, LACMA Archives 3 (2019) from the series Archiving Obsolescence.

Archives and architecture each traffic in a false notion of timelessness, superficially resisting the entropy and change which is inherent — even definitional — to them. As smaller technologies like CD-ROMS or zip drives disappear into obsolescence, so too do the seemingly stable steel and stones of buildings themselves. In his 2016 book Obsolescence: An Architectural History, Daniel Abramson writes, “Not until the 20th century did obsolescence come to be understood as a general condition of change in architecture and cities as a whole — a relentless, universal, impersonal process of devaluation and discard.” Citing examples such as an earlier iteration of Grand Central Terminal, San Francisco’s Mutual Life building, and an entire Boston neighborhood, all of which became outmoded in less than a generation around the turn of the last century, he argues that this capitalist garbage-heaping of the urban landscape is a sort of perverse “creative destruction.” As with other consumer technologies, the trend has only accelerated in the 21st century. This year, in New York, for example, Natalie de Blois and Gordon Bunshaft’s 270 Park Avenue (1960) won the title of the tallest building to be intentionally demolished — JPMorgan Chase had decided they needed a bigger tower. A few blocks away, plans to destroy Trump’s Grand Hyatt are underway. Trump gutted the 1919 building and built it back up in 1980; current developers feel that upgrade has run its course and plan to replace it with a mixed-use building — to be New York’s second-highest — with 2 million square feet of office and retail space, a smaller hotel, and better transit connections. These projects are in part a real-estate battle to retain businesses that might otherwise depart for Hudson Yards, the glittery (and much derided) new district built atop an obsolete railway depot, connected to the Highline, itself a revamp of elevated railroad tracks that fell out of use when freight trains were superseded by trucks.

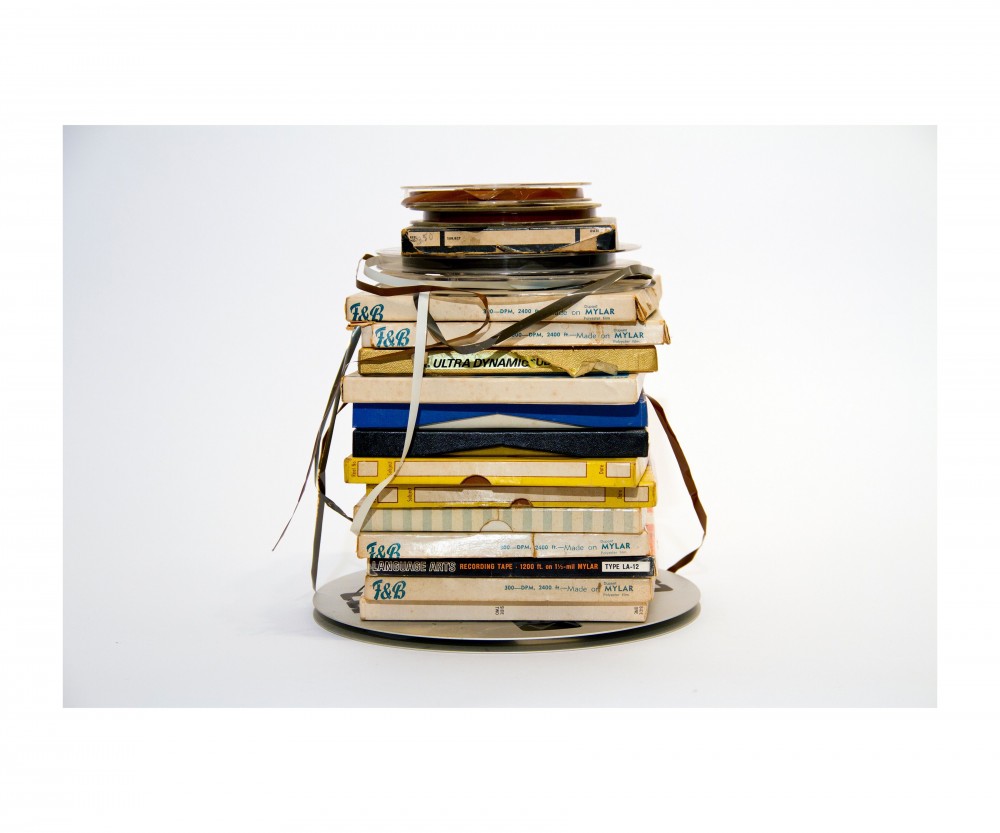

Julia Christensen, Pearson’s Tapes (2014) from the series Hard Copy.

Change and growth are necessary architectural conditions, but the demise of these formerly high-tech towers and files resonates with a dissonance only increasing in the archive, where the resilient, preservable objecthood of storage devices works against the keeping of the information of interest that’s on them. It’s a dialectic of materialization and its dispersal accelerated by the Internet and its impact. The Internet is often discussed as an archive, though one that works in a generative rather than a read-only manner. However, as far as metaphors go, the Internet maps to the physical archive in reverse — that is, “cyberspace” does not actually suit spatial metaphors. As media archaeologist Wolfgang Ernst puts it, “Within the Internet … there is no longer so much a lieu de memoire as there are only addresses. Here the structure of communication is fused together with its contents/holdings.” Archived “files” are not localized like folders in drawers or figures in a memory place, but merely like buildings on a map, something pointed towards. For Ernst, the fact that the archive is not really the web, just “mere metaphor” for it “(belies) the fact that it is not so much that its products are archived than that a transformed ‘disposability’ of cultural knowledge obtains.”

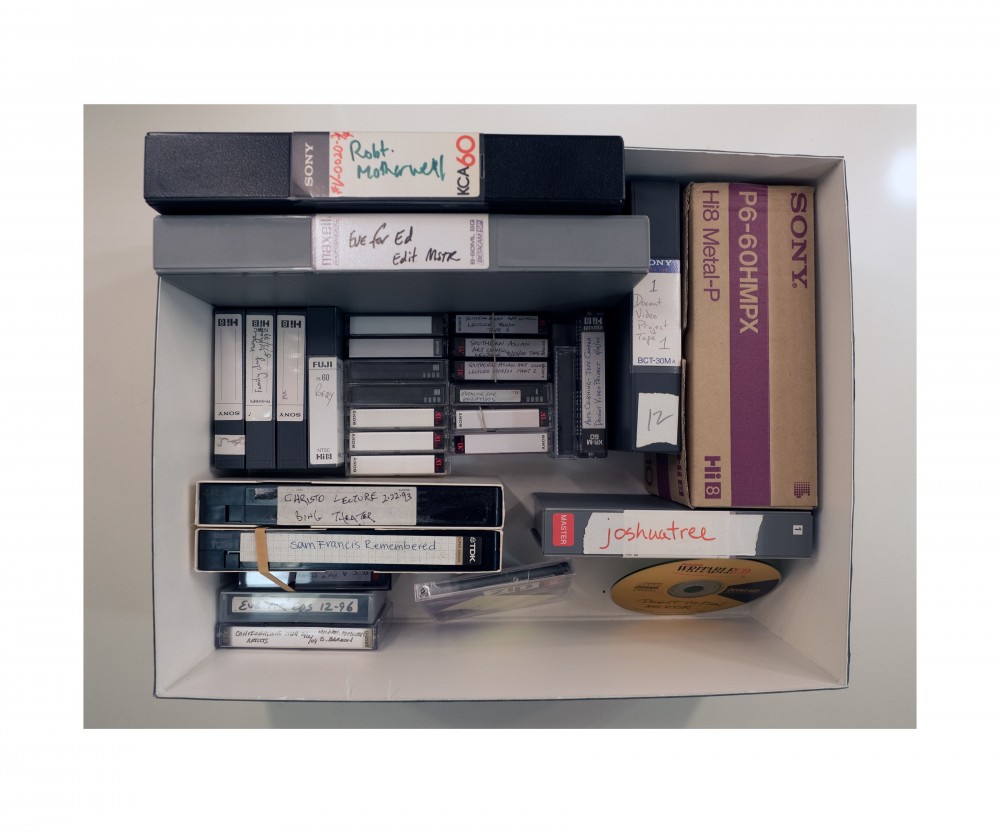

Julia Christensen, LACMA Archives 5 (2019) from the series Archiving Obsolescence.

Conservation is changing. Dragan Espenschied, the preservation director of the digital-arts nonprofit Rhizome explains, “The classic idea of conservation is that someone will take some object through the door of an archive, and then they take care of that discrete thing.” In the case of digital media — which for Espenschied primarily means net art — this approach often doesn’t make sense. Espenschied and his colleagues focus instead on preserving environments — emulators that might run Windows 98, or a specific version of Netscape, say, that keep the art usable. “You have to define the boundary of that work before you can act as a conservator, before you can define what you want to take care of,” he says, noting that just keeping a file intact is not enough, and often doesn’t mean a work is actually viewable or usable. (Wide-eyed NFT collectors take note.) In digital art, this can also beg complicated questions of performance (should things from 2002 run at 2002 speeds, for example) or links kept or lost or the use of defunct application programming interfaces, such as Google Earth’s, which many artists once relied upon.

Julia Christensen, LACMA Archives 6 (2019) from the series Archiving Obsolescence.

The CCA’s Archaeology of the Digital displayed not only models, plans, etc., but also old computers. As Zardini explains, “We inspected a series of layers — authors, machines, software, companies, related disciplines, institutions, etc. — not only to articulate a historical account but, more importantly, to better understand the context that allowed these projects (and technologies) to achieve prominence.” The architectural projects’ remaining ephemera was interpretable as part of a broader archaeology of technology that spoke to the social, material, and ideological conditions giving rise to these techno-fetishistic creations. “You need to be very careful that you’re showing a piece in a way that pays respect to that artifact,” says Espenschied. “In relating the artwork, you have to still make it understandable — and be careful not to get nostalgic.” Context does not serve to bring us back to a lost moment, but rather creates understanding of a work and its significance to our present. To extend a digital metaphor back out, what would an environmental logic to architectural archiving look like — whether in the city, an air-conditioned storage room, or the digital ether?

In mud and stone and clay and gravestones and monuments, the city’s history is both inscribed and lost, a collective textuality of power, resistance to power, and power’s fickleness. Wind and water and wrecking balls and bombs and time smooth these memorials away. As disks decay and software support flickers out, digital codes slip into the inevitability of invisibility, forming an archive of what went missing, and, then, no archive at all. As Ernst puts it, speaking from the mausoleum of our present-past: “Nostalgia for an archival order is a phantasm.” Let us be haunted.

Drew Zeiba is PIN–UP’s associate editor. He also contributes to the Architect’s Newspaper, Artforum, DIS, Metropolis, and New York Magazine.

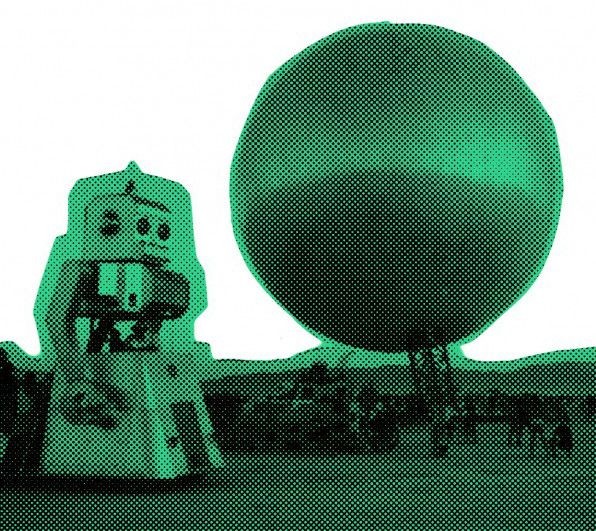

Works from the exhibition Julia Christensen: Upgrade Available presented at ArtCenter (and co-produced by the LACMA Art + Tech Lab), Pasadena, California, September 17, 2020 to June 30, 2021. All images courtesy the artist.