TOXIC POSITIVITY: The Optimism Bubbles of Tech’s New Pioneers

NBBJ, Amazon Spheres (2018). Seattle, WA.

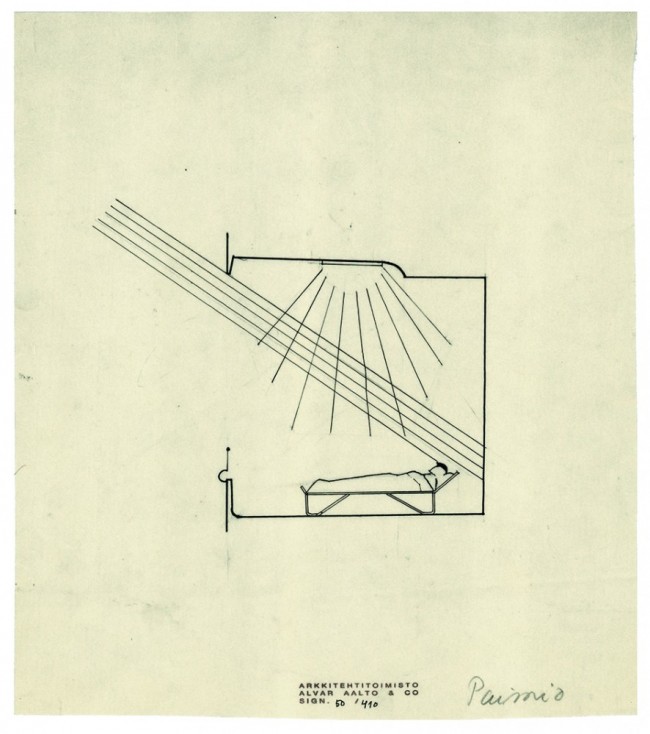

In downtown Seattle, three bubbles float above Lenora Street. Realized in glass and steel, webbed in “biophilic” patterns, they were designed by American architects NBBJ for Amazon. Within their pentagonal hexecontahedrons, 40,000 plants from across the world bloom, some extinct in the wild.

Over the past year, many tech companies’ share prices have doubled, while Tesla stock has risen sevenfold — for the first time, Elon Musk’s electric-car and solar-energy company turned a profit that didn’t involve government credits. In September 2021, Amazon announced a plan to add 55,000 employees globally. Another tech bubble about to burst, according to some economists. But, for true believers, corporate tech growth is not a bubble but our future ripening, our future arriving.

Faith in indefinite growth in the face of dwindling resources, a warming world, rising conflicts, and raging disease seems delusional at best. How can believers remain committed to such concepts of growth? To be a futurist, don’t you need to ensure there’s a human future? The delirious commitment to never-ending growth, the religious fervor in it, reveals not an “accelerationist” cynicism but a comitragic optimism. Time, for techies, is not a line or a curve, but a circle, a sphere, an infinite loop.

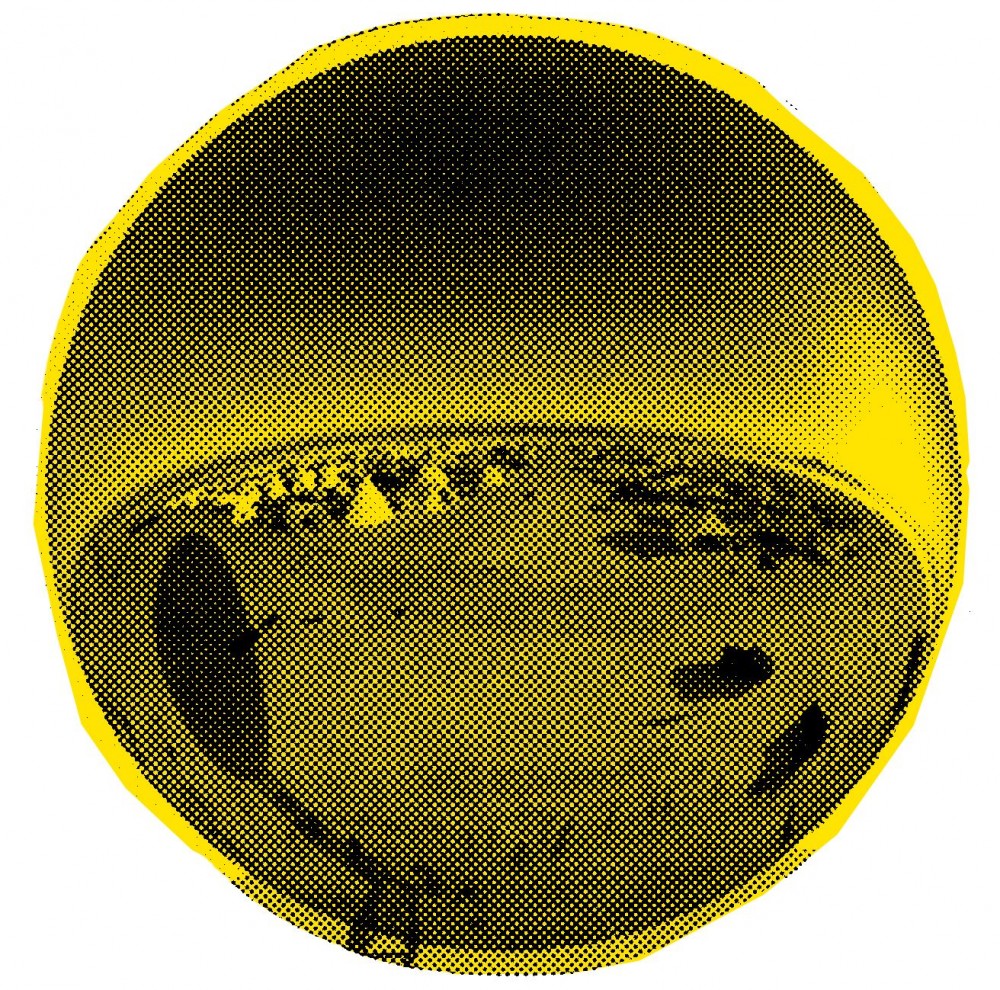

Bjarke Ingels and Jakob Lange, ORB, 2018. Installed in Nevada's Black Rock Desert for Burning Man.

Spiked onto a 100-foot-long steel mast, a giant reflective sphere loomed above the “playa” at 2018’s Burning Man. big.dk’s big ball, the ORB, designed by BIG’s founder Bjarke Ingels and the firm’s special-projects head Jakob Lange, was covered with polyethylene film, the same stuff used for NASA weather balloons. The artwork, the architects explained, was a 1:500,000 double of the planet it hovered above (as if every sphere could not claim some similar relation). “A mirror to Earth lovers,” its fundraising site called it.

Burning Man, some say, has changed: once an alternative solstice ritual it has become the domain of celebrity private-jet setters and the newly minted mega-wealthy who stay not in ragtag tents but opt instead to “glamp” with AC and hired staff. But Burners and billionaires are not such unlikely bedfellows, for techie appeal is woven into the very fabric of the $425-a-ticket festival’s ethos.

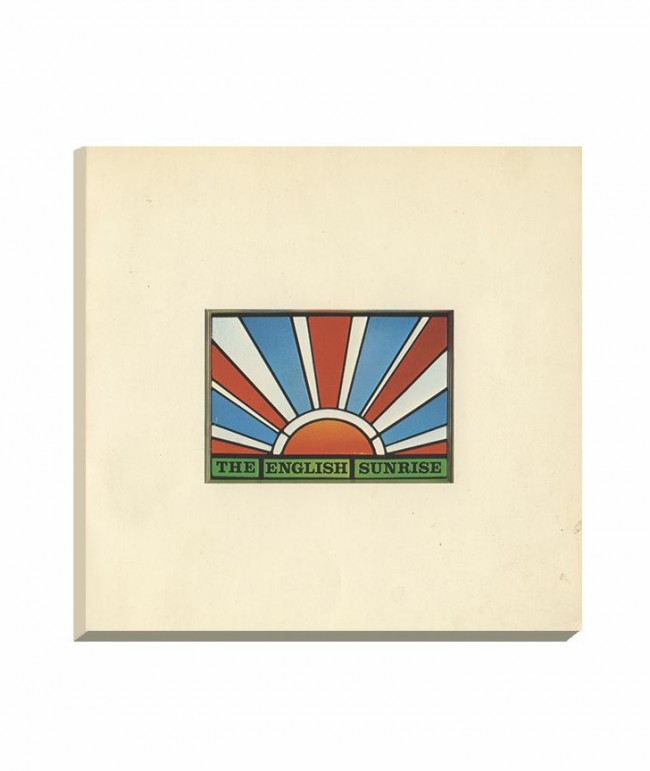

Despite revisionist depictions to the contrary, 1960s hippies were not necessarily neo-luddites who just happened to occupy the same geographical space as proto-tech workers in northern California. The two camps, if not one and the same, overlapped culturally. The best-known example of this synchronicity is the Whole Earth Catalog, published from 1968–71 by Stewart Brand, who, from his beginnings as a writer and photographer, became something of a Bay Area luminary. The Catalog promoted a variety of products for those interested in self-sufficiency and holism, as well as publishing articles and essays that were read widely throughout the Bay area by communards, hippies, arcology advocates, and engineers alike. (In 2018, Brand complained to The New Yorker that he’s often blamed “for everything,” from the sexism of back-to-the-land communes to the monopolies of Google, Amazon, and Apple.)

By the 90s, scholars began documenting what they dubbed the “high-tech New Age” or “New Edge,” the phenomenon of Silicon Valley types invested in “cyber-spirituality.” As virtual reality and the web developed in the Bay area, so too did a spiritualist hope that placed utopian thinking in line with altered states and digital avatarism. To LSD evangelist Timothy Leary, it was clear why the new hippies were pro-tech: the digital realm had “inherent spiritual characteristics.” Some even believed that virtual reality might make language obsolete, inviting a state of spiritual telepathy. Simultaneously, raver and Burner culture grew alongside the tech industry, populated in part by those who worked in it, throwing events that increasingly required digital expertise for promotion and the creation of multimedia environments. Dropping acid to open your mind on the commune (as Steve Jobs famously did), to let go at a party in an Oakland warehouse, or to plug in at your desk while coding represent not a break from one another, but a continuity.

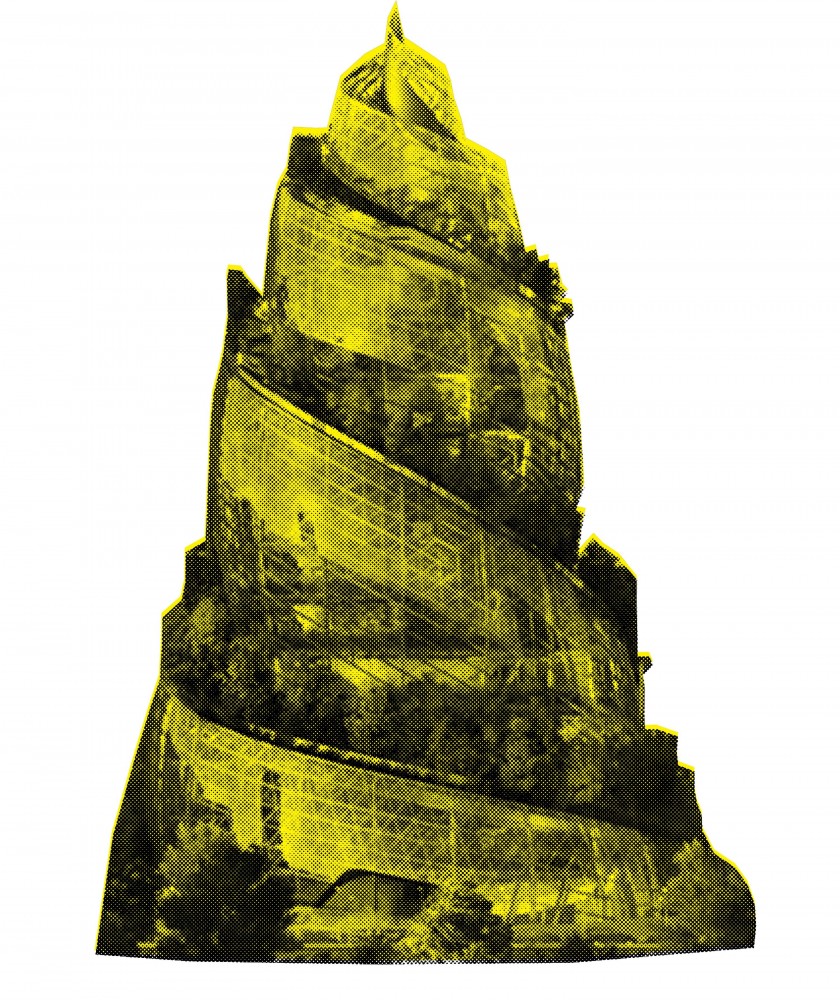

NBBJ, render of Amazon HQ2, in Arlington, VA. Expected completion in 2025.

For Dorien Zandbergen, who studies the history of Californian counterculture and startup culture, this convergent hippie-coder ideological schema in the tech industry reveals not a widespread teleological narrative or materialist orientation but rather a gnostic position, a value system “concerned with the ‘unveiling’ of one’s ‘true being’ and the ‘true nature of reality’” through a “temporality (that is) decisively non-linear, aspir(ing) to the ideal of transcending time altogether, and of creating a sense of immediate connectivity.” Whether through cold saunas, yoga, and starvation, or virtual reality, transhumanist manipulations, and online simultaneity, believers intend to forgo earthly hustle and bustle for an information world of enlightenment and self-realization.

But while “the wrong Amazon burns,” as the passé memes say, is the delusional optimism baked into this worldview not abundantly obvious?

Not if your head is in the clouds, like at Cloud Valley, a recently announced project by BIG in Chongqing, “where people, technology, and nature thrive together — with spaces designed for all types of life: human life, plant life, animal life, and even artificial life.” Or at the top of the 350-foot-tall proposed Amazon HQ2, a tree-lined double-helix — DNA’s shape, discovered with the help of LSD, or so the urban legend goes.

Jeff Bezos’s office workers take lunch breaks by rare rhododendrons while his warehouse employees race against time lest their wages be docked, earning him billions — some of which he has committed to the Long Now Foundation, one of the many ventures that Brand has involved himself in over the half century since the Catalog. Among the foundation’s projects — apart from resurrecting the woolly mammoth and hosting events on “long-term thinking” — is the construction of a massive clock inside a mountain in West Texas, which is intended to tick all by itself for the next 10,000 years. Bezos, by the way, owns the plot of land where the clock is being built.

Biosphere 2, 1987-91, in Oracle, AZ.

“You’re relaxed about your own death, because it’s a blip on the scale you’re talking about,” Brand told The New Yorker. The Long Now is a sort of antithesis to the longue durée, a “now” where history — the work and attention history requires — disappears, where meaningful, reality-based analysis is shrugged off in favor of a facile, rosy view of “how far we’ve come.” From Brand’s position, age 82 with a billionaire as bestie, it might be more heartening to look back than for the rest of us more concerned with humanity’s uncertain future on the longer road ahead.

Oh well. Round and round the clock’s hands spin, like the tubes of an O’Neill cylinder, the space-colony design that was first proposed by Princeton physicist Gerard K. O’Neill in 1976, and which Bezos favors for our floating future. With his aerospace company, Blue Origin (recently called out for having a toxic, sexist, and erratic work culture), Bezos is planning self-contained verdant stations of artificial gravity, packed with a trillion people, home to “a thousand Mozarts! a thousand Einsteins!” But what of us regular folk? Will we be left back on Earth to die on the distribution-center floor? One hopes the space colony’s year-round “Maui on its best day” climes won’t wind up like Arizona’s ill-fated 1991 Biosphere 2 (number 1 being this planet), another infamous pseudo-utopian dream that was meant to prove the feasibility of space colonization, and whose quasi-geodesic folds recall the more leaky Buckyballs of both Amazon’s HQ1 and many a hippie home.

“To live in a dome is — psychologically — to be in closer harmony with natural structure,” according to Drop City spokesperson Bill Voyd. “Domes break into new dimensions.” Through the material, through building, we might exceed our material limits altogether, so the thinking goes. Drop City, an artists’ community and so-called “first rural commune” founded in southern Colorado in 1965, went bust a few years later amid media attention, personality clashes, and general overrun. Such scenes recur at many a startup or commune, or those that split the difference, like Biosphere 2, whose CO2-flushed air may soon enough be not too different from our own.

The utopian dream of circular architecture lives on, even if Buckminster Fuller’s scheme to ensconce all of Manhattan in a dome never came to fruition. However, every bubble defines what and who is kept out as much as in. While Foster + Partners describe their giant “spaceship-shaped” ring for Apple’s Cupertino HQ as “open and connected with nature,” “open” is just an aesthetic category, not a claim to publicness. Jobs’s desire for a circular mothership that appeared less office park than national park is little more than just that: an appearance, a marketing ploy. Which didn’t stop the press from leaping to laud the building, one tech journalist going so far as to say the olive-tree-ringed facility symbolized “a kind of wholeness, a corporate soul.” However, as critics like Kaid Benfield, senior adviser to the Natural Resources Defense Council, have pointed out, the 12,000-employee donut represents an apogee of suburbanism, a bloating of car-dependent spaces funneling people into low-density, high-priced housing while disconnecting the world of Apple from existing urban infrastructure, public services, street life, and, obviously, city taxes. Inside Apple Park, the actual workspaces are little different than any other in the area, even if these starchitect-designed digs are a long way from the garage in which Jobs and Steve Wozniak allegedly began Apple in 1976 — part of the Silicon Valley mythopoesis that blends American Dream entrepreneurship with the area’s countercultural narratives to produce a cult following of tech CEOs that recalls California’s many sinister 20th-century sects.

Foster + Partners, Apple HQ, 2018. In Cupertino, CA.

The countercultural finish brushed atop tech hagiography produces a vision of “California” that integrates Manifest Destiny narratives with the pseudo-sheen of liberation, which in American revisionism is always the liberation of the individual, not the collective. Like the self-help swindler, the gnostic logic of the techno-hippie turns inward rather than looking at the broader structures within which individuals live. That is, their transcendence is committedly apolitical — as were, in fact, many factions of the 1960s’ so-called counterculture. Brand himself said as much when, in 1998, reflecting on the Catalog, he wrote, “At a time when the New Left was calling for grassroots political (i.e., referred) power, Whole Earth eschewed politics and pushed grassroots direct power — tools and skills.” Such a meek positioning of “power,” as something to be wielded by a singular, heroic individual making, say, a dome for their self-betterment, was always ripe to be swallowed by a ravenous — if fruitarian — capitalist mouth. The colonial starward pivot is just another step in this delirious trek, while the West Coast’s vaunted “nature” is paved over or swallowed by fires, sequestered in glass bubbles, and artfully arranged atop shiny new office buildings.

What Jobs or Bezos or Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey, or all those who call such figures their clients — Foster, Ingels, Patrik Schumacher, et al. —, have in common is not merely a commitment to the West Coast “spirit” but also to a certain ideology. By denying the realities of the present, these businesses attempt to invoke awe and sell a desire for a future of unadulterated optimism. But the New Age narratives that prop up Silicon Valley futurism as manifested in the future-present of their architecture do not get “us” nearer transcendence, but in fact expose the increasingly dire and unequal material conditions we exist within and are headed towards. They market a distraction, a sun-soaked present, a star-bright promise.

Bjarke Ingels and Jakob Lange, ORB, 2018. Installed for Nevada's Black Rock Desert for Burning Man.

Apollo 8 astronaut William Anders’s famous photograph of the “Blue Marble” — the Earth as seen from the moon on Christmas Eve 1968 — was featured on the cover of the second and third issues of the Whole Earth Catalog. It has been often argued that the shot, titled Earthrise, helped galvanize the nascent environmental movement by presenting the planet as a thing, not as the world but a world, one for which we are responsible. Zandbergen contends that these photos “were intended to bring the viewer into a profoundly holistic mindset.” In a sense, the photos were deployed to market the belief system the Catalog was selling. Today’s renderings of glinting new AI-powered campuses and unlikely hyperloops, space-settlement concept artworks, and retouched drone photos of glass boxes and real-life buildings operate in much the same way. They’re an invitation to a world of deluded hope for transcendence, one that, back on the ground, fuels the fires that are turning Silicon Valley to ash.

BIG marketed the ORB as “a mirror to Earth lovers,” the kind of trite descriptor befitting the PLUR-laden event. But when the sanitized “peace-and-love” message of the mid-century hippie serves the narratives of big, polluting business, what good is planetary love? Perhaps the only remaining hope is that, at a site like Burning Man’s Black Rock City, we do transcend, we do lose ourselves, become that which may be all that’s soon left — mere images. An empty globe reflects the sky, our promised home, we below, eyes acid-wide despite the desert sun, saucers staring into the great out there, peering at our mirror image, the mirror image of us stuck on the dry, warming ground, waiting to rise above. Or no, we can’t see ourselves, can’t wave at our virtual doubles on this foreign planet — within minutes the shimmering ORB has dimmed, dulled by a dirty coat of desert dust.

GET YOUR COPY OF PIN–UP 31 HERE.

Text by Drew Zeiba

Taken from PIN–UP 31, Fall Winter 2021/22.