IRISH DESIGN: Five Days Of Discovery With Orior

There’s the sobering warmth of Scandinavian Modernism, or the sophisticated opulence of Italian design. There’s the pragmatic rationality of the Germans and the Swiss, the studied whimsy of the French, or the heavy humor of the Dutch. But when someone says “Irish design,” most draw a blank. Wanting to know more about the Emerald Isle's rich material culture which date backs to the Iron Age, PIN–UP recently accepted an invitation from the furnituremakers at Orior and spent five days getting a taste of what's new — and of what’s great and old — in Irish design. With a landscape punctuated by medieval architecture, quarries packed with stones found nowhere else on Earth, and enduring traditions of craftsmanship, it’s high time that the island nation gets its due. (And if you're in New York you can also see Orior’s latest collection in their new Tribeca showroom.)

Two Livia ottomans: left in solid oak with Mr. Hide fabric in Mandarin from Jerry Pair; right in walnut with First Love fabric in Rosé from Holly Hunt.

Lia Chair in Bisley fabric from de Le Cuana in the colorway Emperor.

Atlanta sofa in Viggo fabric by Pierre Fray, Matelot colorway.

Mara credenza with a solid green Irish marble top and leather coverings in Apple and Hunter.

DAY 1

I met up with my host, Ciaran McGuigan, whose family has been in the furniture business for decades. His parents, Brian and Rosie, who immediately greeted me with a hug (and offer of wine), started the business Orior Furniture in 1979 in Newry, Northern Ireland.

Making every piece to order in the workshops they have in both Newry, part of the United Kingdom, and County Kildare, part of the independent Republic of Ireland, the family business — which includes cousins, family friends, even children of craftspeople who have been with the furnituremakers since the beginning — specializes in working with materials sourced from Ireland and across Europe. Apart from its multi-decade heritage, Orior Furniture has made something of a name for itself as of late, working on contract commissions like the recently-revamped legendary club Annabel’s in London. They’ve also made a splash across the pond with a Tribeca showroom that opened this past May.

As Ciaran and I rode through the low mountains punctuating the seaside along the border of the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland in his black Mercedes, his stories upon stories were sprinkled with the names of friends and friends-of-friends, a friend’s mother’s cousin’s aunt, and so on, illustrating a portrait of the business as an extended family.

Ciaran explains that he’s trying to pivot the company his parents started away from contract work and back to its roots, presenting himself and Orior as a designer of collectible furniture. The company will be crafting small collections or single pieces on their own schedule, with each piece remaining entirely made-to-order.

At the top of a mountain in Kilkeel, Northern Ireland, we pull into the dusty drive of local stonecutters, whose shop produces components for Orior’s furniture works, as well as major architectural commissions — think limestone façades — and monuments. When I visited, there was a new D-Day memorial bound for Normandy underway, the monumental scale of which felt even bigger spread across the workshop.

While it might not have the same fame as Calacatta or Carrara, Ireland is renowned for its stone. This is old earth, and each region’s quarry has unique traits and coloration, though possibly most distinct is Connemara marble, a green stone mined from Galway with deposits as many as 600 million years old. Its mossy hue, of course, gives it a stereotypically Irish character that most of the stonecutters and designers I talk with are more than happy to embrace.

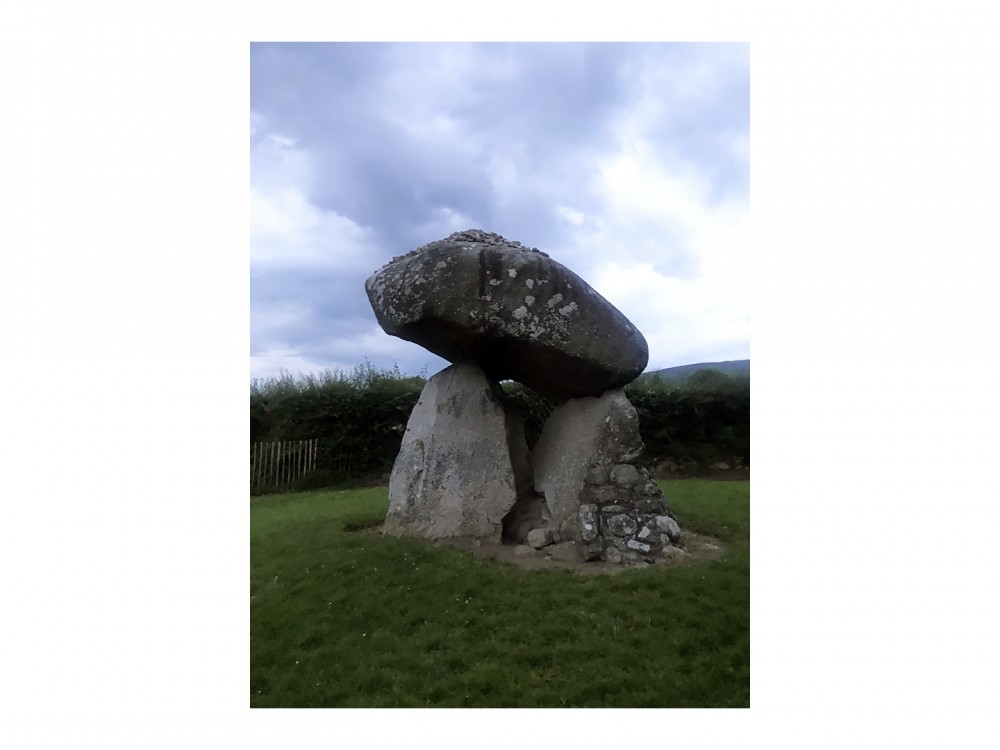

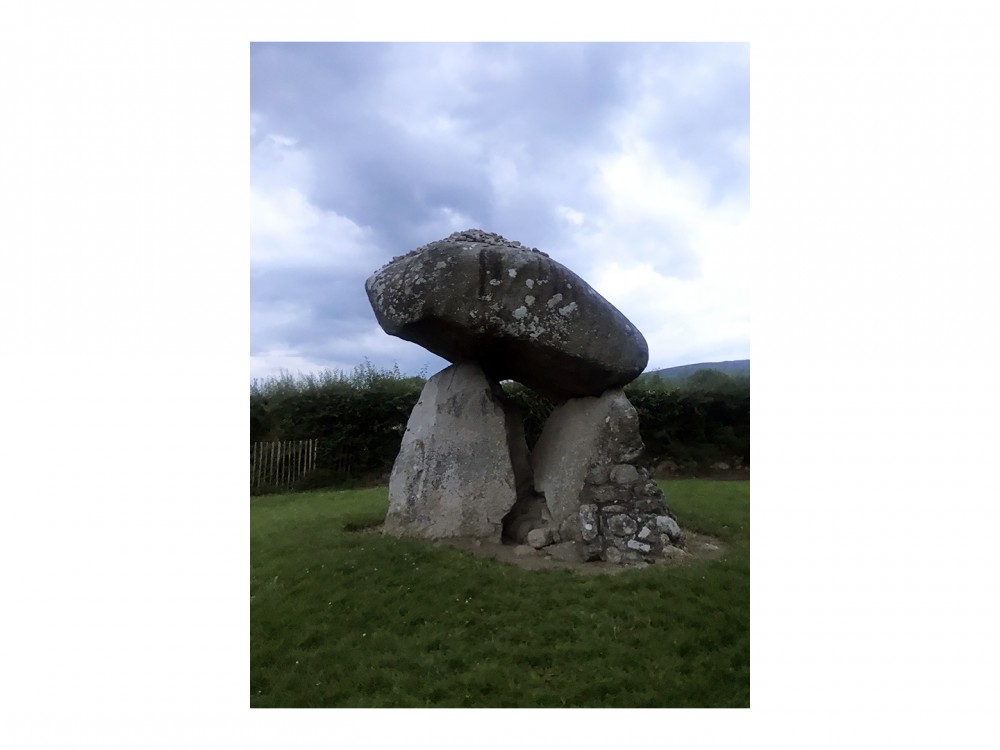

Proleek Domen. Photography by Drew Zeiba.

I was able to encounter some of the island’s storied stonework just beyond my hotel’s golf course. Proleek Dolmen, a sort of mini Stonehenge, is a ten-foot-tall “portal tomb,” built some 5,000 years ago. A giant boulder mounted on prongs of thinner rocks, despite its seeming precariousness, the monument has endured the island’s many changes.

-

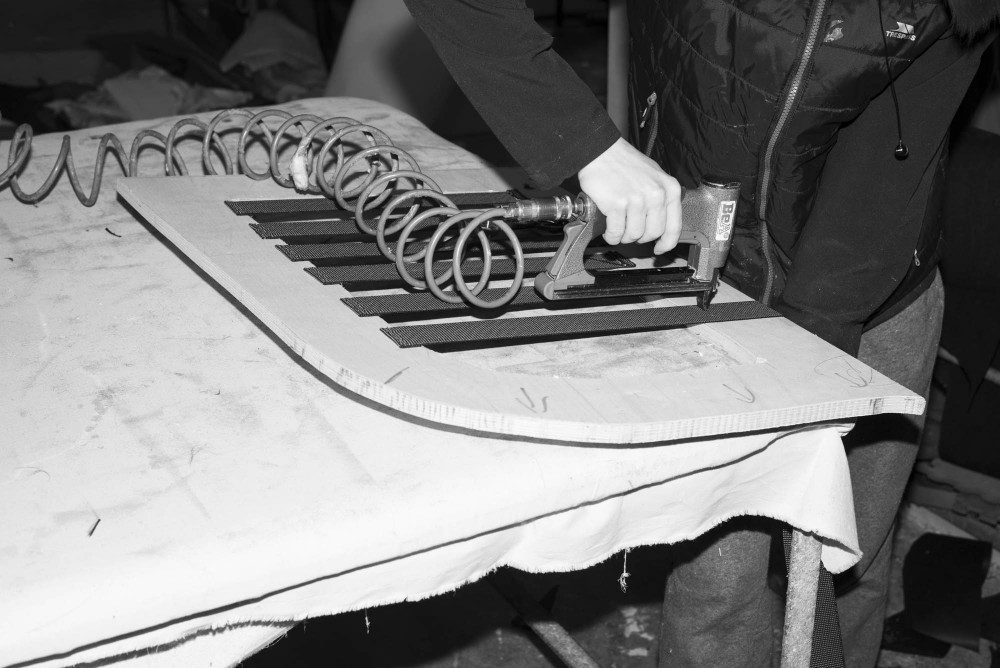

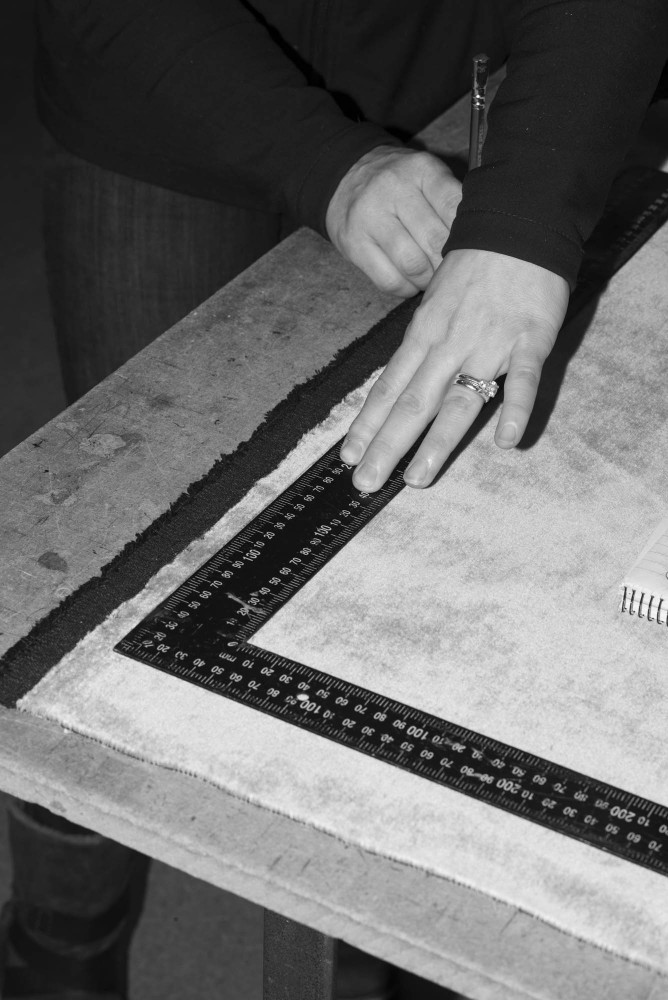

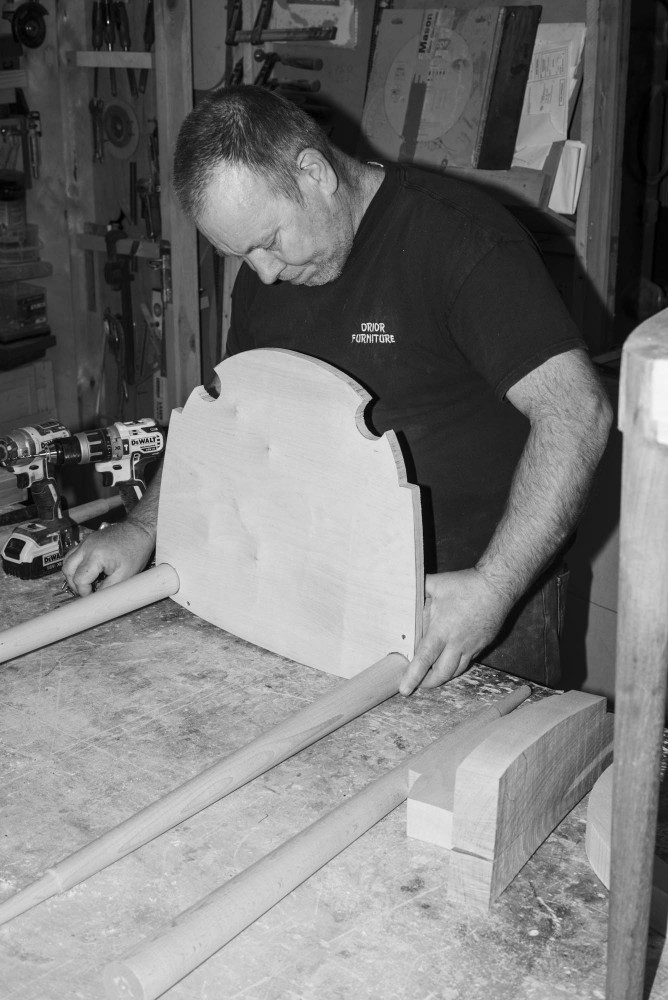

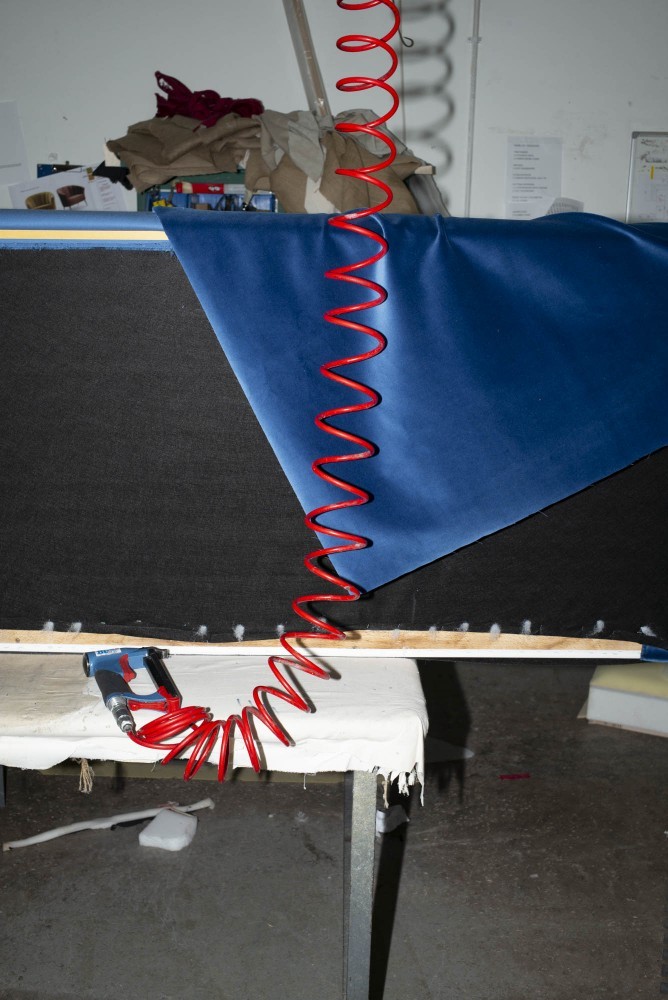

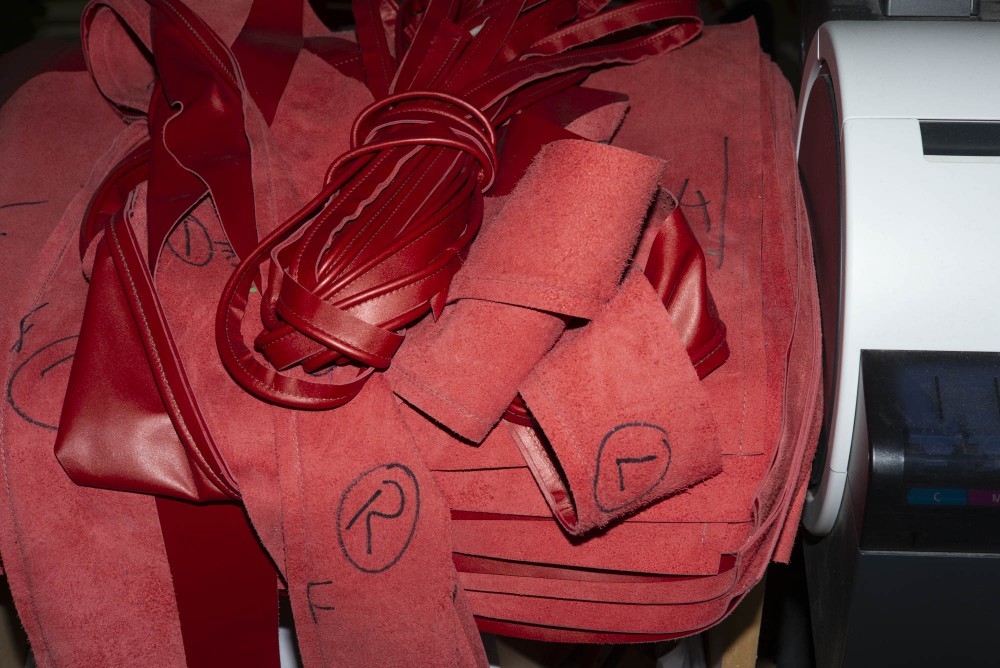

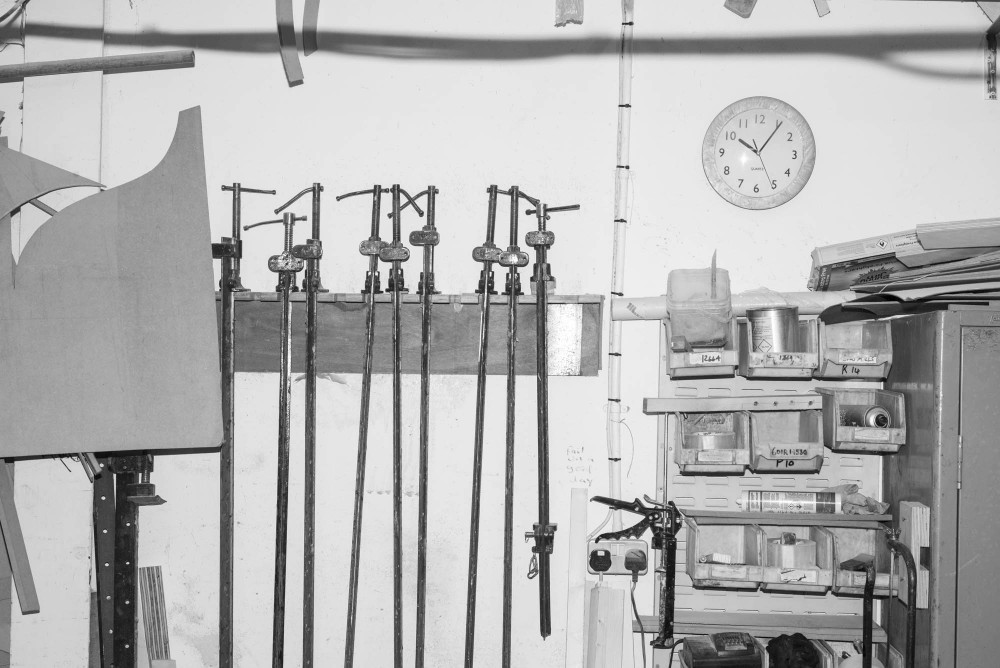

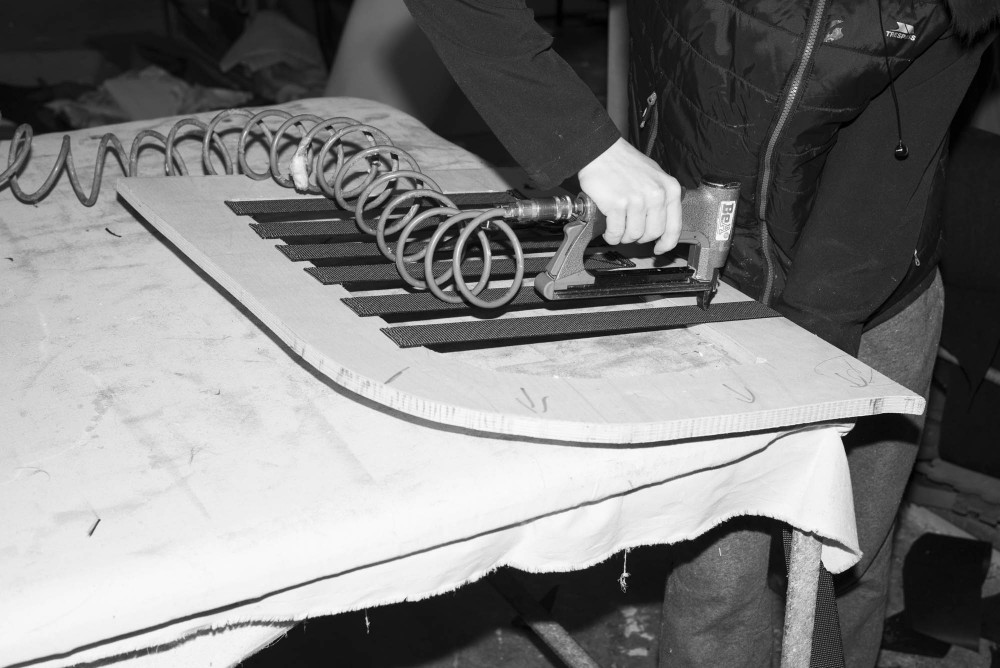

Manufacturing process at Orior’s factories in Newry, Ireland.

-

Manufacturing process at Orior’s factories in Newry, Ireland.

-

Manufacturing process at Orior’s factories in Newry, Ireland.

-

Manufacturing process at Orior’s factories in Newry, Ireland.

DAY 2

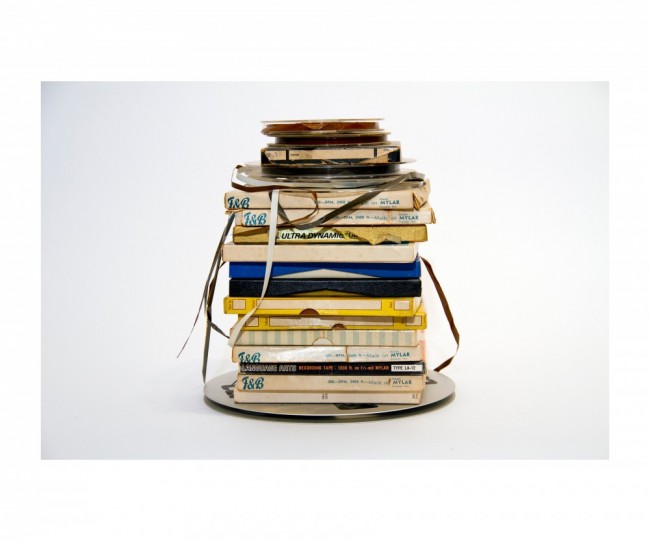

I paid a visit to the Newry-based factory where Orior’s business operations take place and where they keep their library and archive, as well as upholster furniture, working with many expert craftspeople who have been with the company for decades. Some are even second-generation. We chat to upholsterers who have known Ciaran longer than he can remember and expert sewers who work in a loft surrounded by a fabric library with leathers and other textiles in every imaginable color. (Touching allowed!)

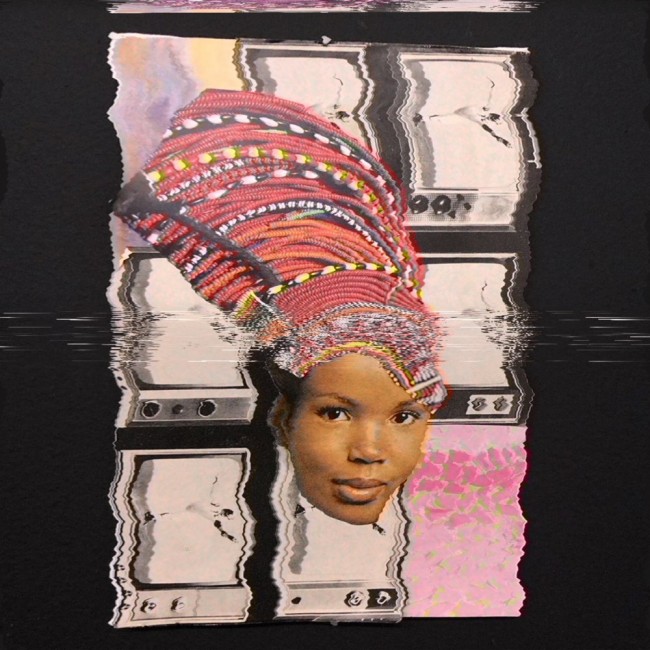

In the office, moodboards cover the walls. I wondered if the image of a woman wearing Louboutins, the red heels scuffed to oblivion, or the architectural shot featuring chrome pipes were references for a campaign, but Ciaran explained that these diverse influences directly inform the furniture. He takes inspiration from across time and media, from the design world and beyond when drawing up new furniture plans, capturing a feel as much as a design feature.

DAY 3

Just north of Dublin, an unsuspecting country road reveals The Vintage Hub, a seemingly endless warehouse space of vintage design, from suits of armor to ultra-chic mid-century modern that’s been restored onsite. One could easily pass hours in this multi-story veritable design archive, picking out oak credenzas and walnut tables. I was particularly smitten with a pair of lucite lamps, art deco cum L.A. bachelor pad vibes. It’s here, Ciaran says, that he derives much of his inspiration. He also left with some new chairs for his Brooklyn apartment — while he makes frequent trips back to Ireland, New York serves as his home.

The Vintage Hub. Photography by Drew Zeiba.

Further south, in County Kildare, we visited the Orior workshop known for some of the island’s most complicated woodworking and cabinetry. Beautifully fluted cylinders of oak were being cut and lacquered by one of Orior’s master woodworkers, to later be placed into a hefty chunk of Connemara marble to become Orior’s Nero table. (Ciaran says that while some computationally-assisted machining is unavoidable, they try to minimize it, and every piece is always hand-finished).

-

Manufacturing process at Orior’s factories in Newry, Ireland.

-

Bianca chair.

-

Manufacturing process at Orior’s factories in Newry, Ireland.

-

Manufacturing process at Orior’s factories in Newry, Ireland.

-

Manufacturing process at Orior’s factories in Newry, Ireland.

DAY 4

Perhaps it’s unsurprising that design in Ireland has near-ancient origins. The island’s rich history that informs today’s contemporary design activities includes Celtic, Norman, Norse, and English influences, Cromwellian protestant iconoclasm, and Catholic, as well as pre-Catholic pagan, object-images. From medieval castles to wearable torcs, there’s a lot to draw from.

Exterior Kilkenny Castle. Photography by Drew Zeiba.

Kilkenny Castle was built between 1195 and 1213 by William Marshal, 4th Earl of Pembroke on the site of an earlier castle made of wood. It went through significant remodeling in the Victorian era, and is today undergoing restoration again. While the massive, eight-century-old building is unarguably impressive, the thing that struck me most was an oddball Victorian seat: upholstered in red and gold, the trippiness of its pattern encouraged by its expanding blobby form and the proto-hippie vibe of its all-over fringes. Fringes are in — Orior’s own fringed Atlanta chair attests to that — but as with most styles, nothing is ever really new.

-

Interior Cathedral Church of Saint Canice. Photography by Drew Zeiba.

-

Interior Cathedral Church of Saint Canice. Photography by Drew Zeiba.

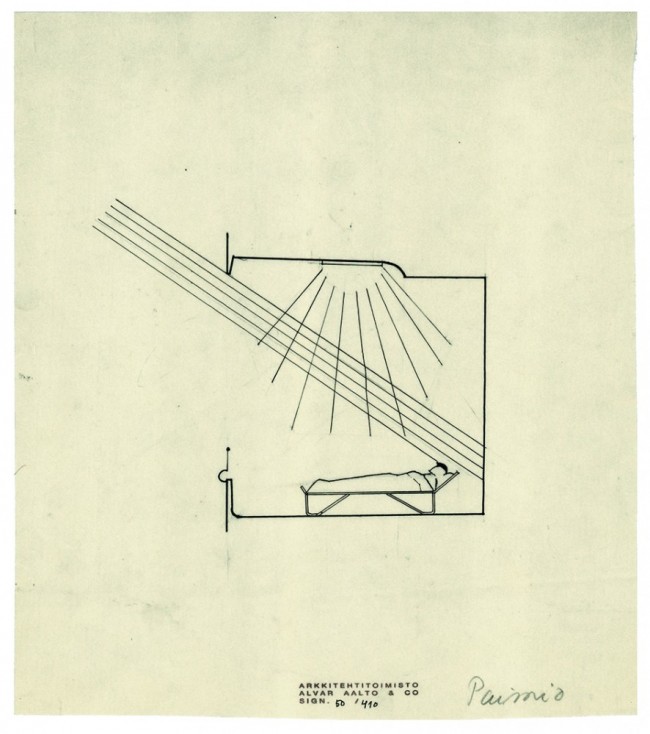

Also in Kilkenny, the spoils of Ireland’s quarries are on full display. In the Cathedral Church of Saint Canice, built in the 13th century, the sanctuary floors (added in the 19th century and designed by architect Richard Langrishe) show off four types of marble each chosen to represent a different region of Ireland, and in their arrangement are meant to evoke a unity of traditions and communities on the Irish island.

DAY 5

After a bi-national tour around Ireland, all this talk of origins and national characteristics has me wondering what we mean when we say something like “Irish design." Ciaran, while proud of the Irish origin of their manufacturing and the local origins many of their products’ materials, is wary of such an epithet — pointing to Orior’s own growing popularity across Europe and in the States. In an era defined by global exchange and the flattening effect of the internet on aesthetics, what is the usefulness of these particular narratives? While context is always key for anyone turning to the past for inspiration, the question of what we mean when we call something, for example, distinctly Irish, seems increasingly prescient in a time when conservative impulses towards defining “national identity” are more and more commonplace. And these same impulses threaten the livelihood of companies like Orior, which depend on working on both sides of the two Irelands’ still-open border, whose status a no-deal Brexit puts into question.

As the October 31st deadline fast approaches, perhaps designers like Orior serve to show how appreciating the unique history of one’s home can serve as motivation to create and share widely — whether across Ireland’s once fraught border or with design aficionados back on this side of the Atlantic.

Text by Drew Zeiba.

Orior launched their new collection in October 2019 at their Tribeca Showroom.