Fernando Laposse Brings Indigenous Mexican Crafts to Miami

-

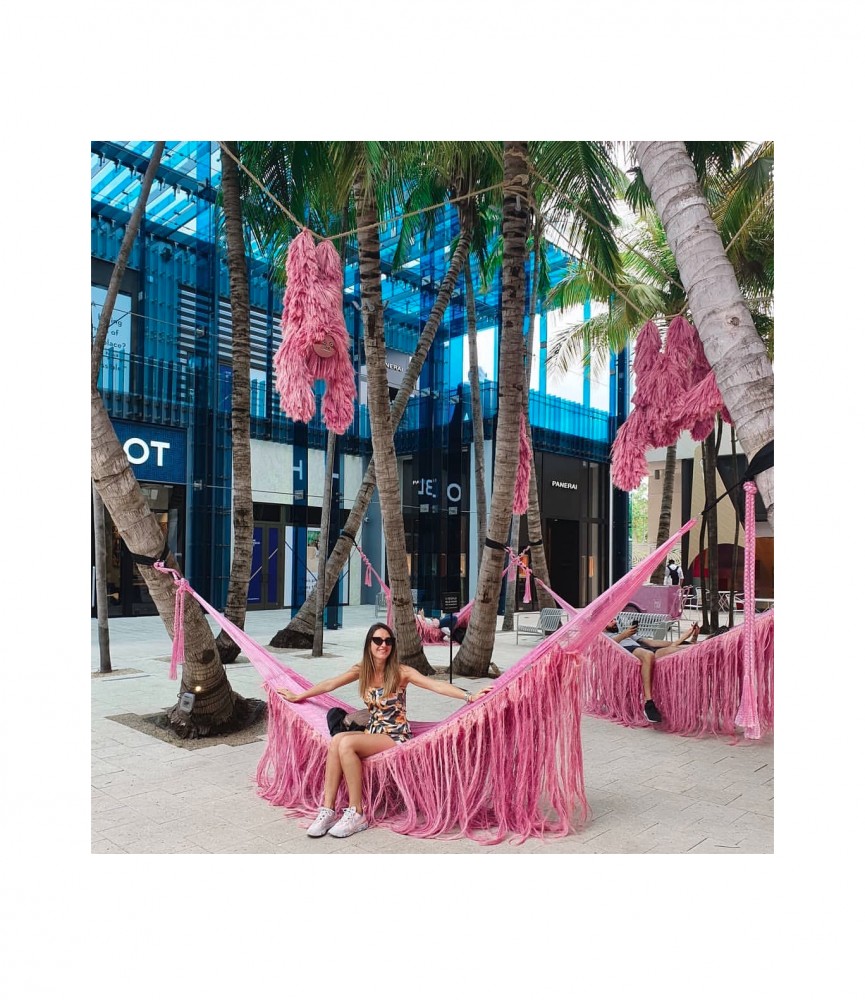

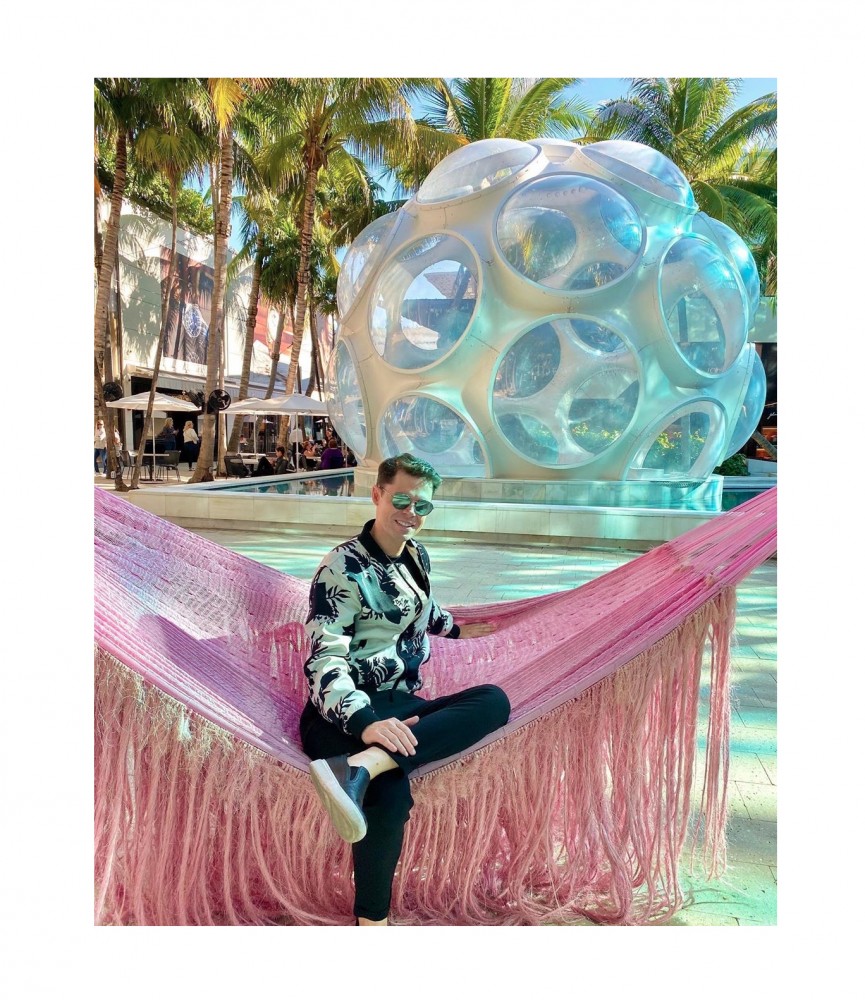

Fernando Laposse installation at the Miami Design District. Sourced from Instagram.

-

Fernando Laposse installation at the Miami Design District. Sourced from Instagram.

-

Fernando Laposse installation at the Miami Design District. Sourced from Instagram.

-

Fernando Laposse installation at the Miami Design District. Sourced from Instagram.

-

Fernando Laposse installation at the Miami Design District. Sourced from Instagram.

-

Fernando Laposse installation at the Miami Design District. Sourced from Instagram.

-

Fernando Laposse installation at the Miami Design District. Sourced from Instagram.

-

Fernando Laposse installation at the Miami Design District. Sourced from Instagram.

“It's an Instagram playground,” Mexican-born, London-based designer Fernando Laposse says about his Miami Design District installation — 10 hammocks, 30 sloths, and 25,000 hanging tassels, all vibrant millennial pink, dispersed amongst the shopping destination’s luxury stores and pedestrian walkways. And indeed as we toured the installation Pink Beasts there were plenty of people posing and pouting for pics, making clear the shaggy design works were an influencer magnet and a cute place to “chillax” during last week's hectic Miami Art Week. But more than photogenic fun, Laposse’s project is a social practice collaboration with farmers and artisans from the Yucatán, making economic opportunity while highlighting indigenous craft traditions.

All the pieces in the installation were handmade from henequén, a species of agave from the Yucatán region that produces resilient twine, a utilitarian material used by the Mayan people to make everything from hammocks to cross-body bags which then became a global export in the 19th and 20th centuries used for marine ropes and coffee bags. For his installation Laposse colored the henequén pink with a traditional Aztec dying technique from Oaxaca, another part of Mexico, which takes cochineal insects that infest the prickly pear cactus, crushing up the female bugs to make a crimson powder rich in carminic acid. “This project,” explains Laposse, “joined the visions of two different indigenous groups.”

-

Henequén, a species of agave grown for sisal. Photo by Fernando Laposse.

-

Fernando Laposse (right) and collaborator Angela Damman (left). Photo by Pepe Molina.

The Central Saint Martins alum had previously used henequén in his installation for the 2018 London Design Festival called Sisal Sanctum, but he left the fiber its natural blonde. This year the theme the Miami Design District gave applicants was “color” and Laposse immediately thought about combining henequén and cochineal. “When you crush the insects, they become a deep burgundy which creates a really intense red dye, but because they’re very pH sensitive you can change the color,” Laposse reveals. “If you use lemon juice, for example, the dye goes into oranges. If you use baking soda or quicklime, it goes into purples. To make a pink, you have to balance a mix of both.” The pink Laposse calibrated feels perfectly reminiscent of a Miami sunset.

The designer notes that a few years ago when the design district was in its early stages of development, there was more space for huge installations. But when he was conceiving Pink Beasts he did a site visit and realized “there wasn’t that much floor space anymore.” His solution was to engage the area vertically, hanging pieces from trees and archways. He had the idea to design sloths — a mascot of environmental preservation in Latin America which also gesture at “the idea of slowing down” — and he also thought to make hammocks in collaboration with Angela Damman, an American-born, Yucatán-based designer known for her use of henequén and who people had kept tagging in photos of Laposse’s London Design Festival installation. The two designers started talking and realized they had both been collaborating with many of the same women artisans in a remote village in the Yucatán near where Damman lives.

-

Sloth and hammock from Fernando Laposse’s Pink Beasts installation. Photo by Pepe Molina.

-

Sloth under construction. Photo by Pepe Molina.

-

Sloths from Fernando Laposse’s Pink Beasts installation. Photo by Pepe Molina.

-

Henequén tassels dyed with cochineal. Photo by Pepe Molina.

Both Laposse and Damman are motivated to find new markets for henequén craft products, noting two main factors have contributed to the fall of the industry, leaving the area economically challenged. After the Mexican Revolution 1910–20, Laposse explains “the wages that people demanded to go in and spend all day under the sun cutting the leaves by hand went up.” Then since WWII synthetic fibers have gradually replaced henequén sisal in many of its industrial applications. “The price of labor increased and the industry just kind of couldn’t compete with his new challenger, the plastic industry.”

Damman explains that projects like Pink Beasts and her own line of handbags and home decor “gives attention to the value of these materials and the heritage of these Mayan cultures, hopefully to create more opportunities and helping them to continue to prosper.” She also explains that different projects push them to experiment and innovate their traditional techniques. “They’re artisans, they’re creative people, but sometimes they don’t get much exposure to the world of design and projects like this help inspire them and open them up to more possibilities.”

The process of working with indigenous farmers and artisans is unique. “It’s really inserting yourself in the community and making the extra effort to accommodate the people’s needs,” says Laposse, who’s followed a similar paradigm in his collaborations with Mixte communities in south western Mexico’s Puebla region, making marquetry material out of corn. For Pink Beasts, he explains the pieces weren’t made in workshops but in the women artisans’ homes. “They don’t have separate rooms. It's one big room, and they have these hooks for the hammocks and so at night that’s where they sleep, but during the day, they unhook the hammocks, and we’d have 30 or 40 women at a time, all working together and chatting.”

-

One of the Mayan artisans commissioned by designer Fernando Laposse. Photo by Pepe Molina.

-

Henequén harvested in the Yucatán region of Mexico. Photo by Pepe Molina.

-

Henequén being processed. Photo by Pepe Molina.

-

Women artisans from the Yucatán working in their homes. Photo by Pepe Molina.

Laposse contends that it’s powerful to have works made through this process in the design district among all the high-end fashion houses. “It’s maybe hinting to them, ‘Hey, there’s another option. Luxury does not have to be made at the fancy atelier in Paris. It can also be collaborating with a small village and preserving their traditions.’” He adds, “In fashion and luxury, it’s all about stories. This is about diversifying the storytelling.”

Text by Whitney Mallett.

Photography by Pepe Molina and Fernando Laposse.