HALL OF MIRRORS: Halston’s Rise and Fall and The Link to New York’s Olympic Tower

It’s 1978, New York City: in Olympic Tower at 641 Fifth Avenue, through the marbled lobby, up the elevators to the 21st floor, and past an unmarked door are the extraordinary new headquarters of Halston Enterprises: lair of the master of minimalism, the legend of Studio 54, the seminal fashion designer of the decade, Roy Halston Frowick. Halston, as he styled himself, came to fame in 1961 when he designed the iconic pillbox hat that Jacqueline Kennedy wore at her husband’s inauguration, and by the end of the decade had opened his own design house whose clients included Lauren Bacall, socialite Nan Kempner, Liza Minnelli, Elizabeth Taylor, and Barbara Walters. Halston’s name became synonymous with the triumph of modernism as the new mode of luxury; his brand of minimal, austere, sensual, and explicitly sexual glamour was de rigueur for the beautiful people who filled the era’s celebrity magazines and gossip columns, and women bought his clothes in droves.

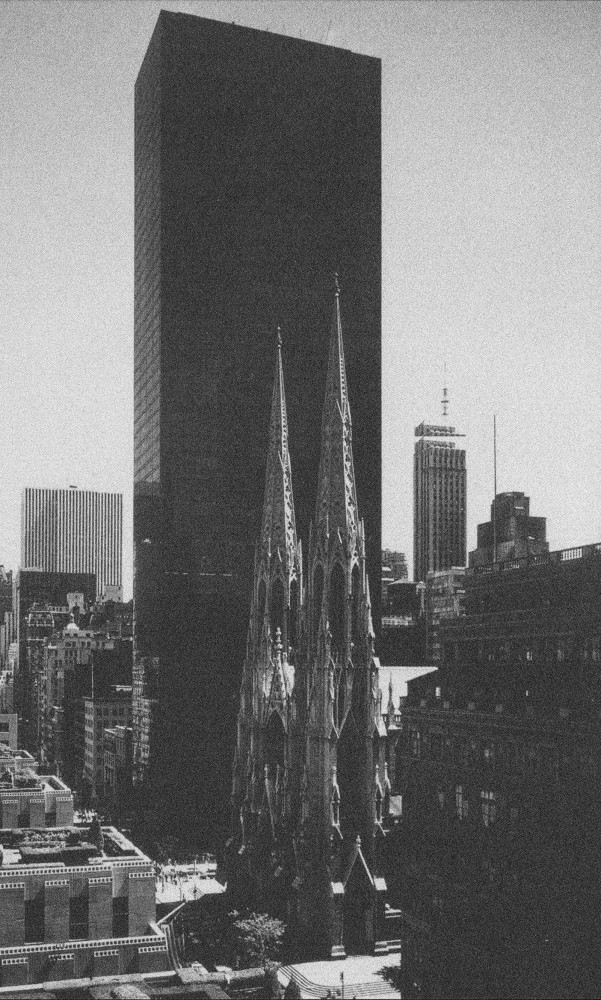

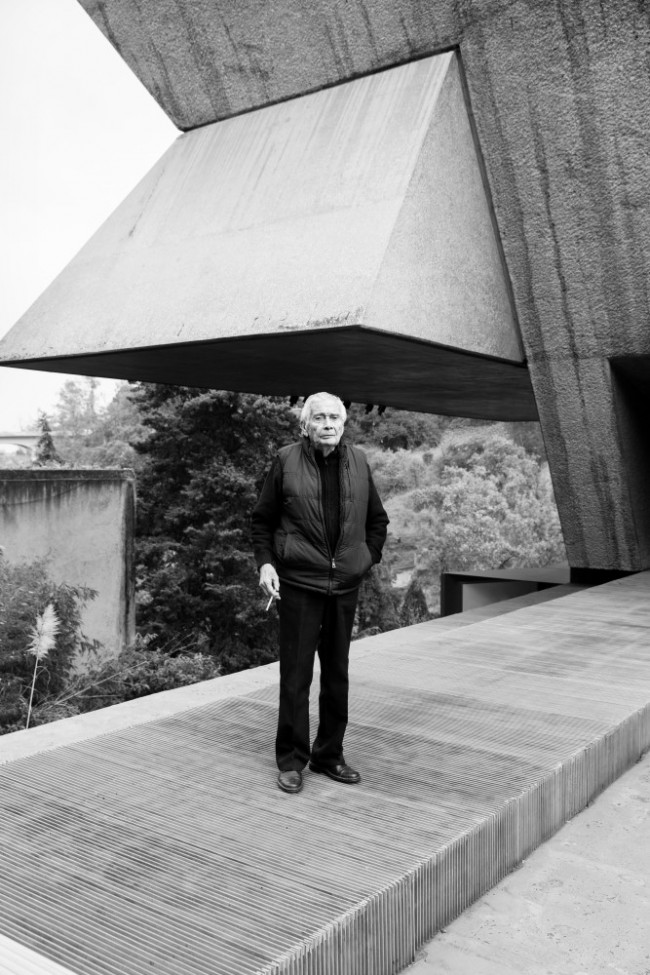

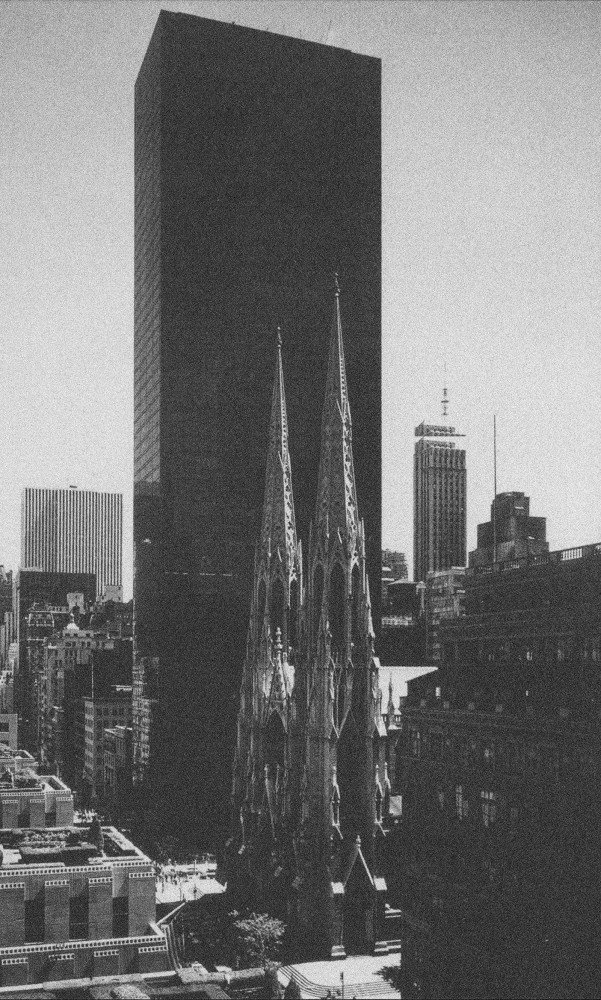

Designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill in 1975, the 51-story Olympic Tower’s Modernist dark glass façade reflects, and dwarfs, the neo-Gothic ornament of St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Fifth Avenue. © Bo Parker, 1978

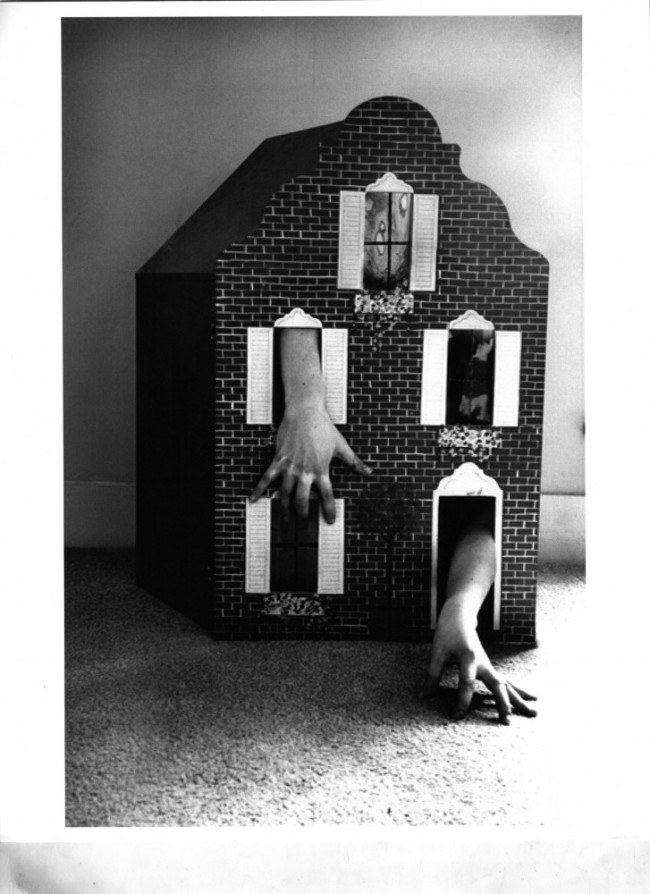

At the height of his success, Halston moved his business into sumptuous premises occupying the entire 21st floor of Olympic Tower. Their scale further inflated by 18-foot-high ceilings, the office’s entirely glazed external walls offered a panoramic view of the Manhattan skyline — the drama of which was in turn magnified by the fact that every interior partition was covered with mirrored glass, producing floor-to-ceiling reflection ad infinitum. In this dizzying glass box suspended in the sky Halston’s minimalist inclinations were brought to their apogee, but in reality it was one of the most excessive headquarters ever created for a fashion company, its cost — both to create and to maintain — proving astronomical. For Halston, it would mark the turning point where the easy-going, all-natural pace of the 1970s gave way to the larger-than-life, bigger- is-better, more-is-more mentality of the 1980s. But wallowing in his minimalist excess, Halston would find himself at the beginning of the end. The mirrored walls of his architectural hubris reflected an indulgence that sent him spiraling downward, falling from the graces of the fashion world and eventually losing everything — his name, his company, and his life.

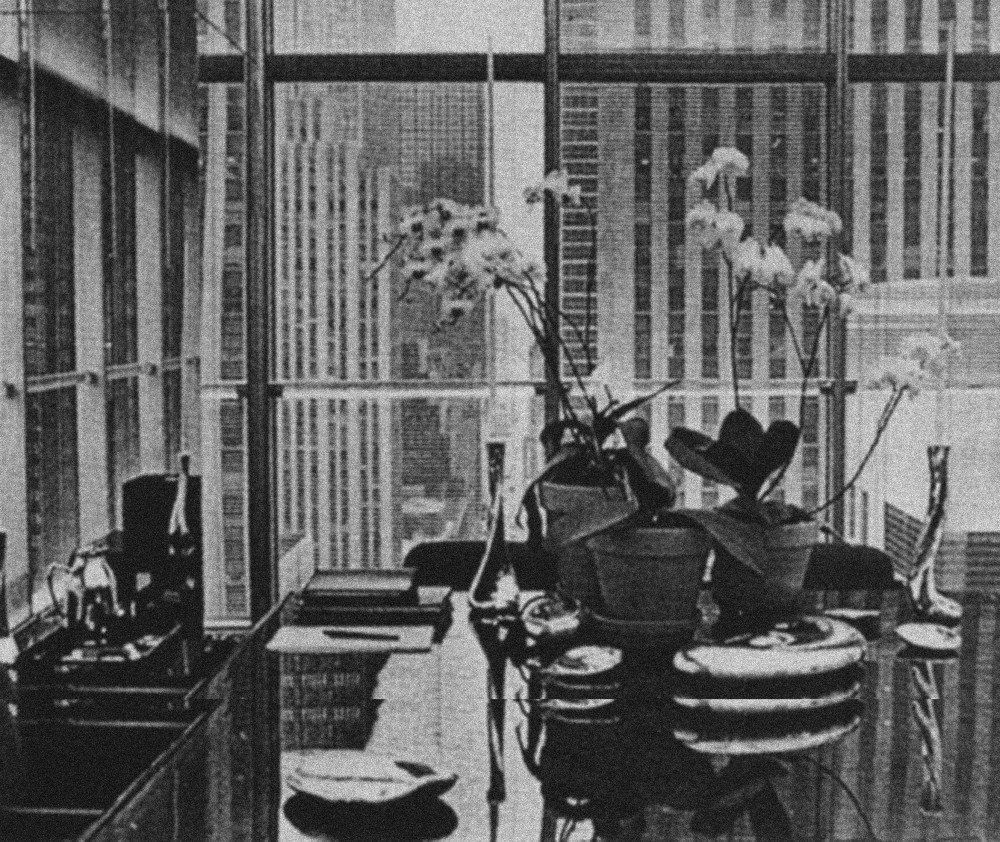

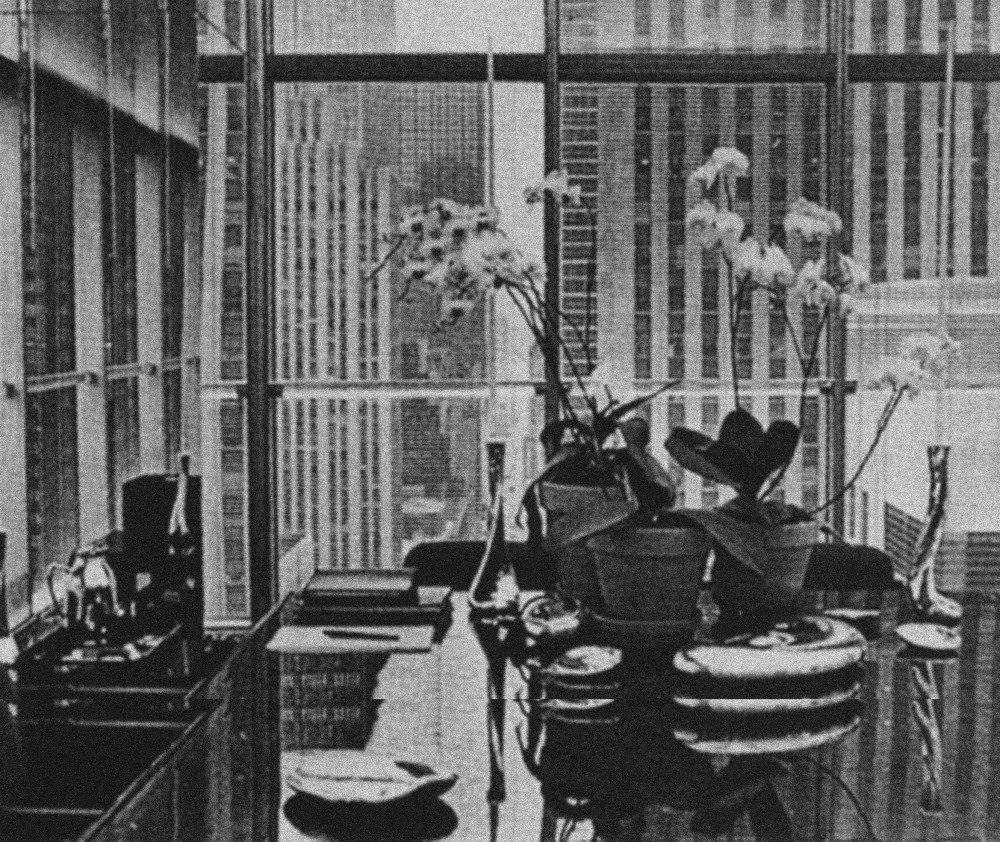

A classic still life of Halston’s “corner office” table, replete with his signature white orchids and custom-designed tableware by his friend Elsa Peretti, c. 1978. © Jade Albert

The path to ruin began in 1973, when Halston’s success caught the eye of Norton Simon, Inc., a conglomerate that owned Avis car rentals and Max Factor, then a discount-store cosmetic line. Enticed by Norton Simon’s vast financial resources, Halston agreed to sell them his company, which also included his name. Business-wise, Halston was at the vanguard of the fashion industry, which had never before seen such a celebrity designer, or anyone who knew how to turn that cachet into a multi-million-dollar enterprise. Norton Simon’s chairman David Mahoney saw Halston Enterprises as a glamorous addition to his stable of significantly less glamorous businesses — that a single name could connote such detailed and developed associations of luxury and desire was unheard of outside of the fashion world. Halston, of course, could only have been thrilled by the fortune he made from the sale, and the possibility of his name and vision conquering the world.

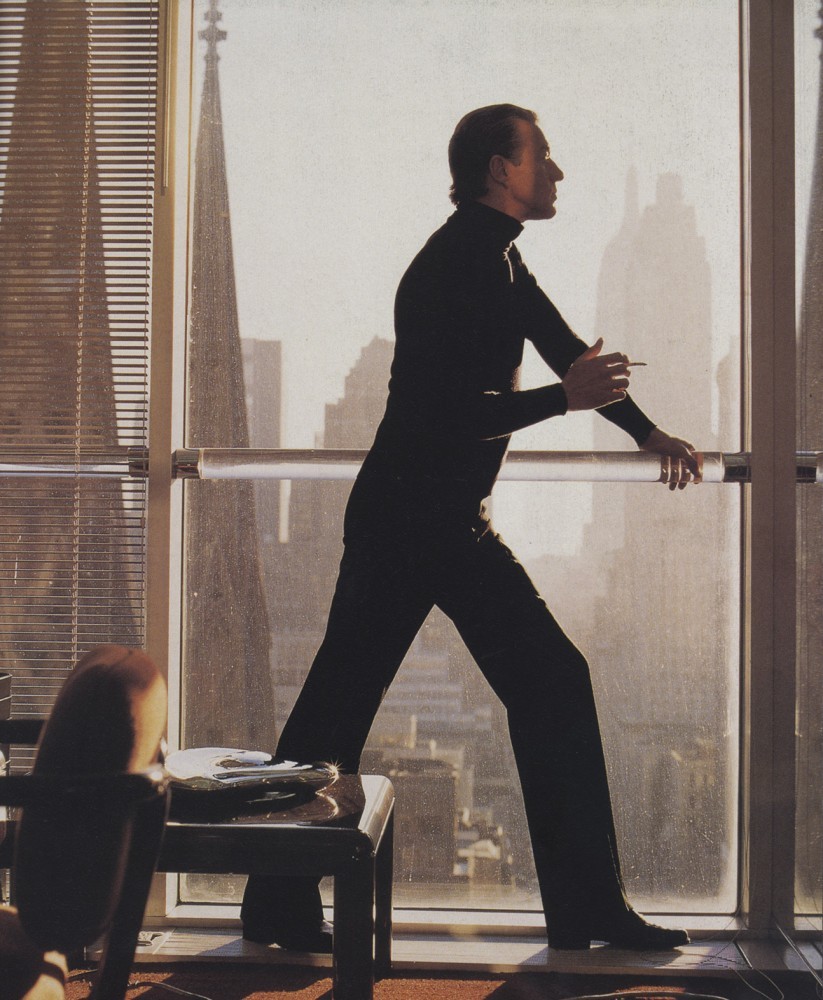

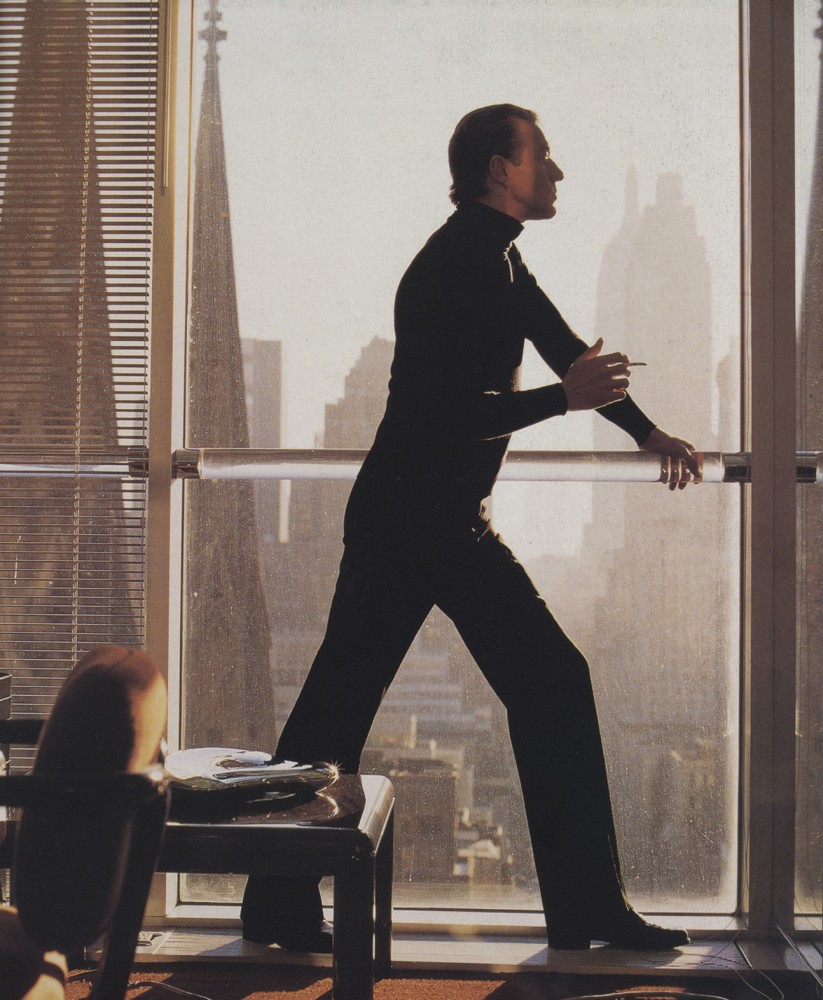

After collaborating with architects Gruzen & Partners on the design – and after nine long months of construction – a proud Halston poses against his new office’s 18-foot-tall windows. © Horst, 1979

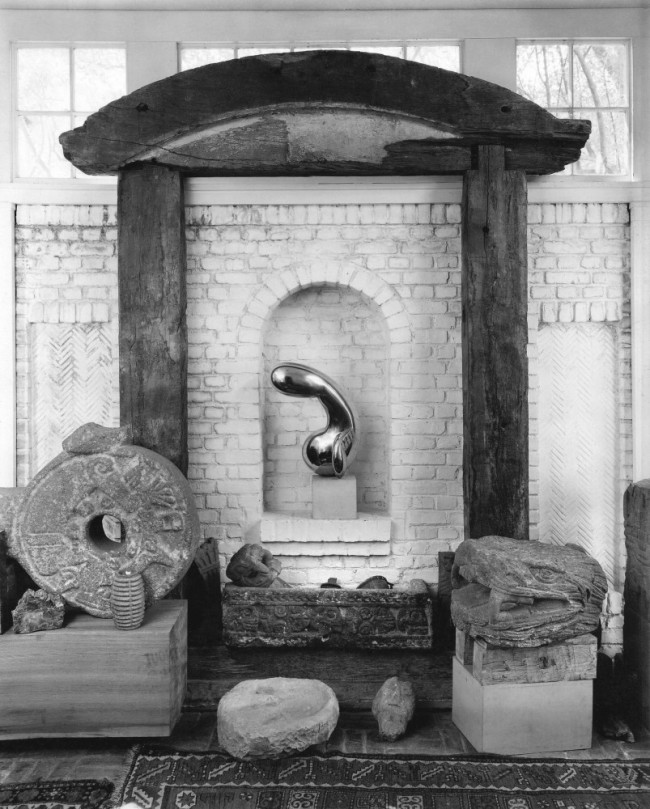

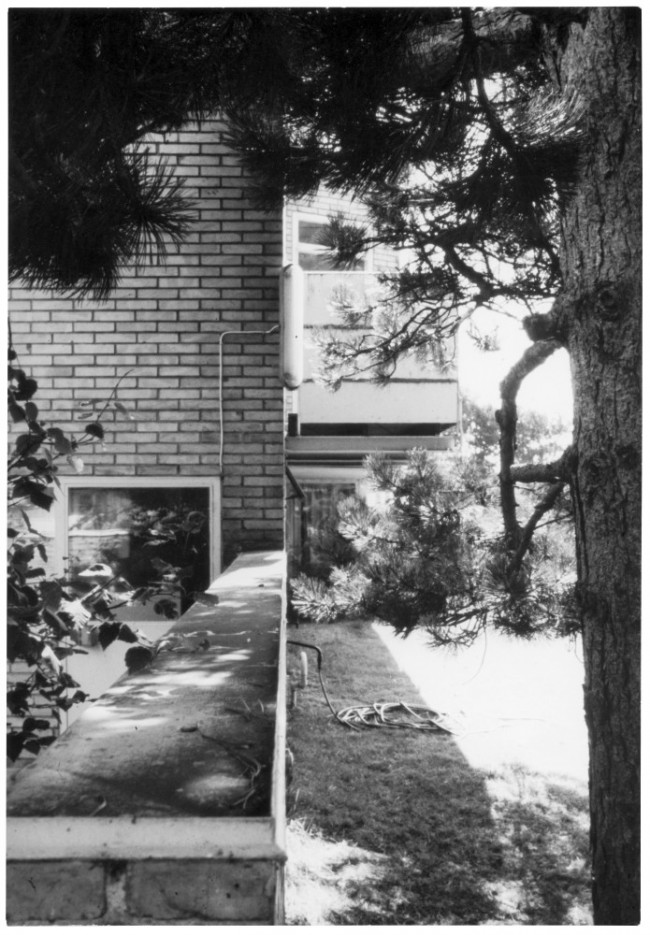

Soon after the sale to Norton Simon, Halston’s personal life had a notable change of scenery with his purchase of a townhouse at 101 East 63rd Street, which had been built by Paul Rudolph for real-estate lawyer Alexander Hirsch and his partner, Lewis Turner, in 1967. An example of Rudolph’s patrician Modernism, the house embodied all the minimalist splendor of Halston’s aesthetic ambition. As the designer put it, “I know this house was built for somebody else, but I really feel as though it was built for me.” Its dark-glass street façade was relatively unassuming, hiding a dramatic interior whose culmination was a three-story, glass-roofed white living room, which Halston carpeted and upholstered in cool gray Ultrasuede (a synthetic microfiber designed to mimic the plush feel of suede) that had become his signature fabric. Over the years the East 63rd Street residence would become notorious for its parties and social gatherings, with stories abounding of raucous soirées, drugs, and sex orgies. The goings-on at “101” would become as central to Halston’s legend as his clothes.

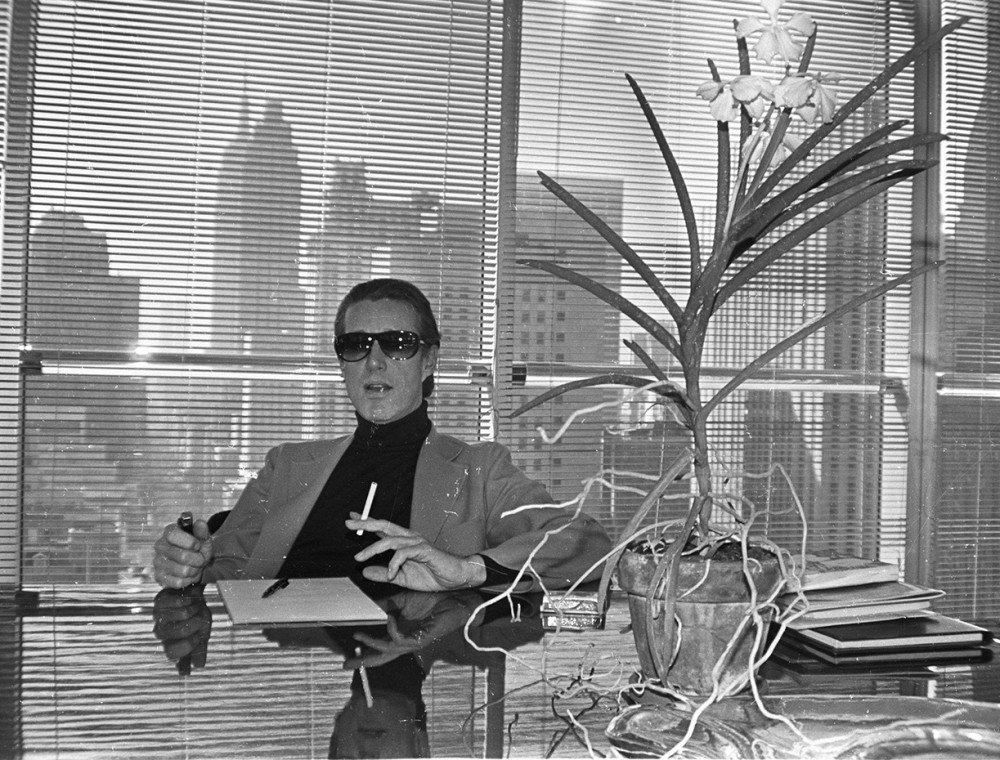

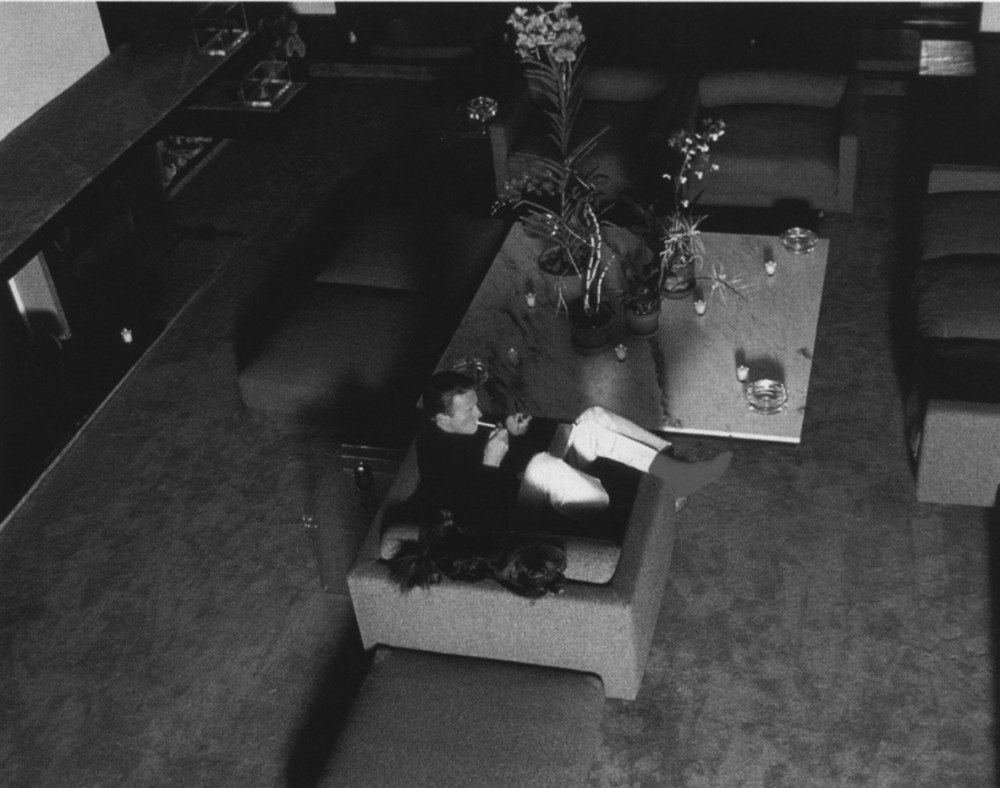

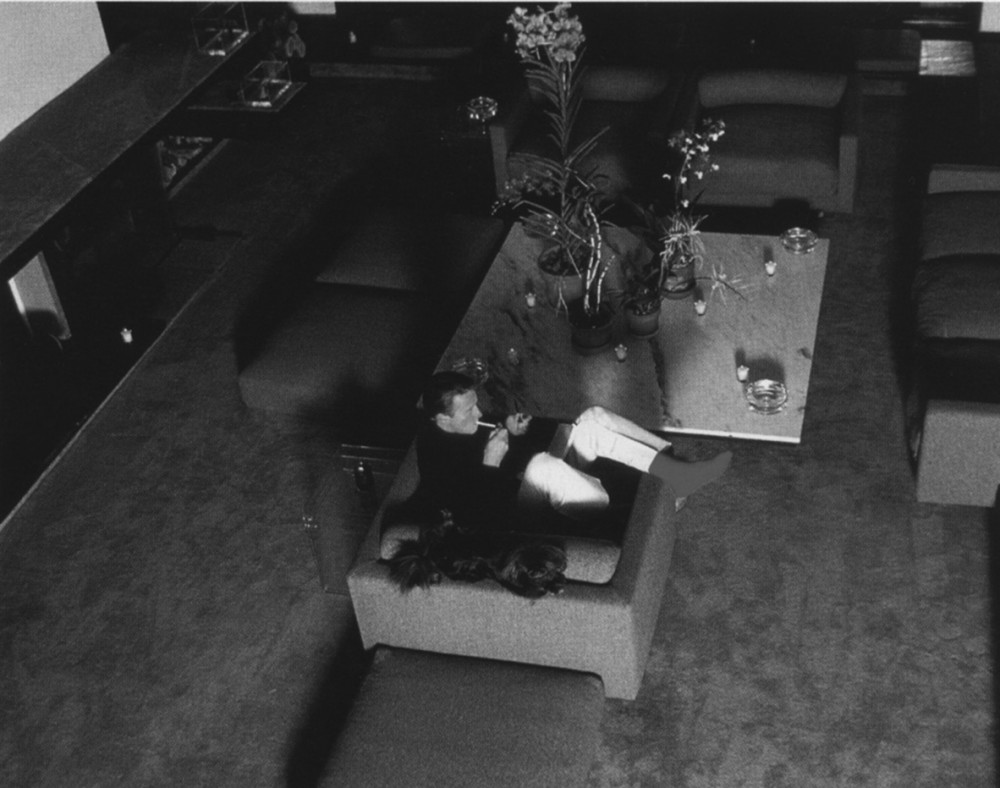

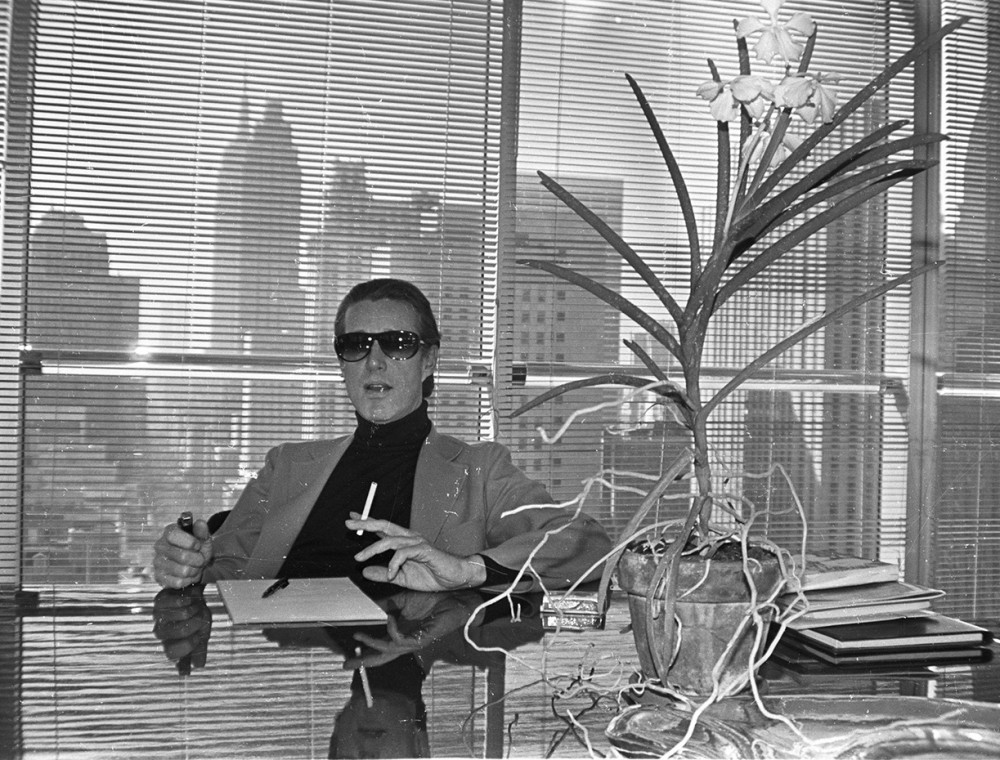

Whether at his desk at Olympic Tower, or at his home in the Paul Rudolph-designed townhouse on East 63rd street, cigarettes and orchids were a constant in Halston’s life. Photograph © Harry Benson, 1978

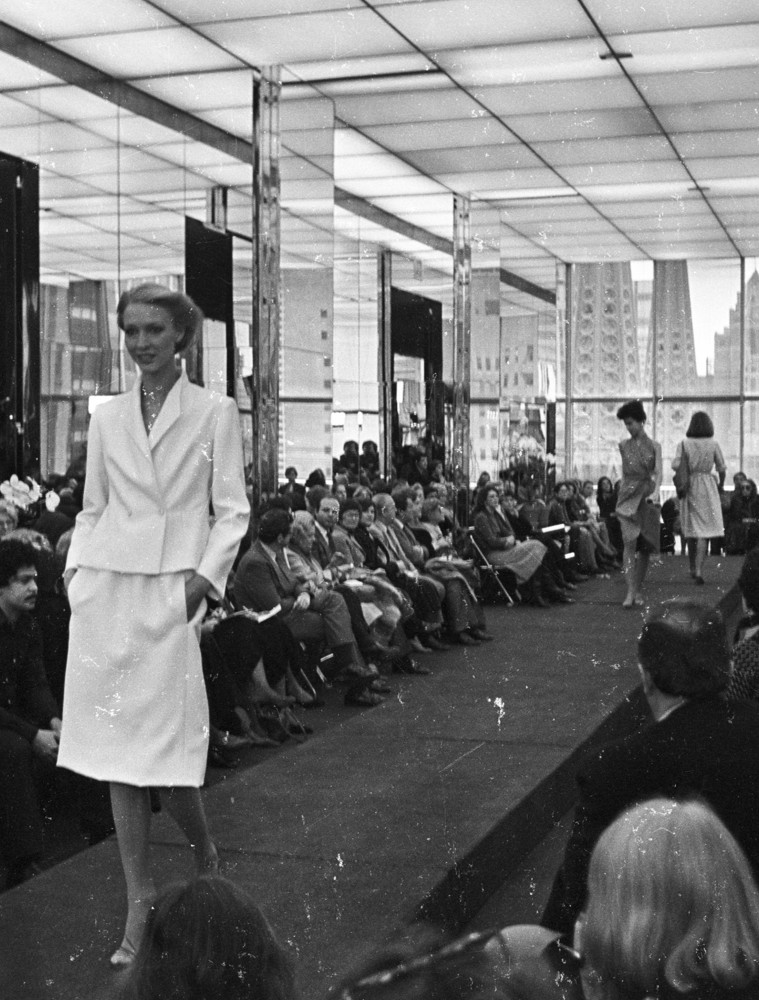

Meanwhile, with the support of Norton Simon, Halston Enterprises developed considerably, and by 1977 had outgrown its cramped space on East 68th Street. The search for a new location for the ever-expanding empire began. On visiting Olympic Tower, Halston was immediately convinced it was the spot. Completed in 1975 by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) — famed for Chicago’s John Hancock Center (1965–70) and Willis Tower (1970–74) — the 51-story dark-glass megalith is located right next to St. Paul’s Cathedral at 51st street, and was a pioneer on Fifth Avenue in its mix of both commercial and residential space in one building. The 21st floor was the tallest of all the commercial floors at 18 feet high (one-and-a-half times the height of the others) and offered a view of Central Park to the north and Wall Street to the south. Halston designed the interiors of the 12,000-square-foot U-shaped space himself, with help from Gruzen & Partners, dividing it into the north-facing workroom — then considered the second finest in the world after Yves Saint Laurent’s — and a 90-foot-long hall that most of the time was compartmented by four full-height mirrored doors into spaces for Halston’s office, a conference room, and two fitting rooms for private clients.

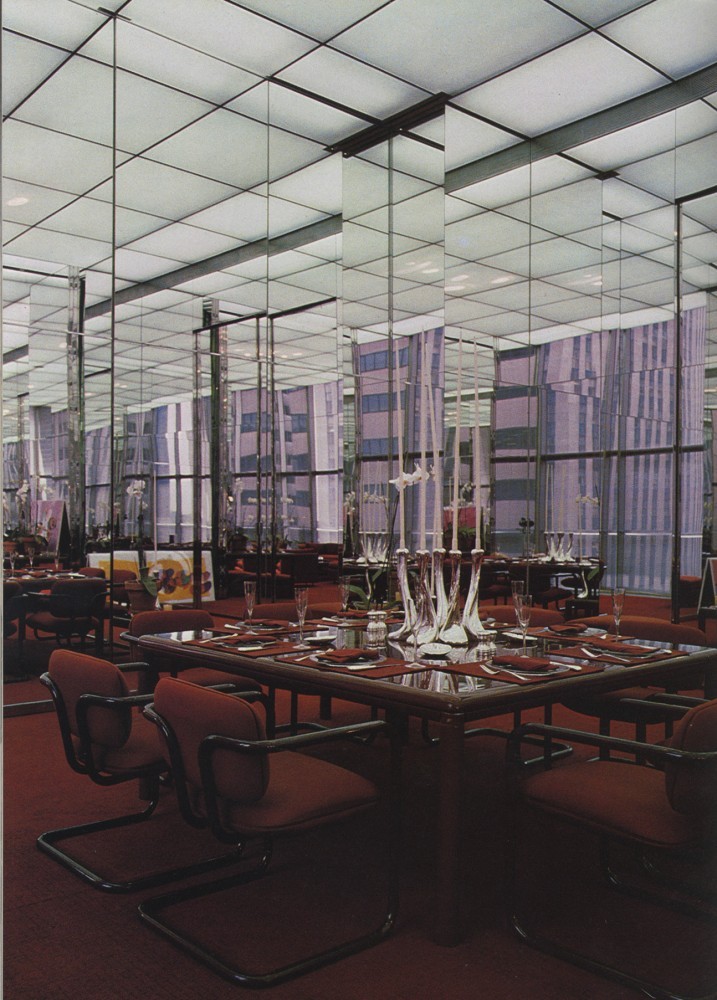

Halston’s minimalist excess extended to the office’s dining room – complete with glassware, dishware, and tableware from Tiffany’s – where he would hold regular luncheons. © Norman McGrath, 1981.

Given that they weighed 1.5 tons each, it took nearly a month to bring the doors up in the freight elevator without their cracking. Each one was perfectly balanced on a hinge so that the entire room could be converted, at a touch of the hand, into a theater for staging Halston’s fashion shows or a banqueting hall for formal dinners. Capping the glorious mirrored walls — which required constant maintenance to clean away marks and fingerprints — was a luminous ceiling in frosted glass, while on the floor was dark-red carpet: “Living high up in New York, everything is gray. I needed something that would stabilize the space so the room wouldn’t float,” as Halston explained. It was actually his good pal Andy Warhol who suggested dark flooring, but it was Halston who designed the carpet’s connecting “H” motif which was developed by interior-textile manufacturer Karastan. The office space was open and stark. Filing cabinets and papers on desks were strictly prohibited. Halston’s own desk was a red-lacquered Parsons table produced by SOM designer Charles Pfister, a model that was also used throughout the showroom. Almost the only decoration was provided by thickets of Halston’s favorite white orchids, which ran up an annual expense in the lower six digits. Other accoutrements were limited to objects created by former model, friend, and Tiffany’s jewelry designer Elsa Peretti, most notable of which were a sterling-silver ashtray and candlestick (still available at Tiffany’s today). For runway shows and special events, a whole battery of furnishings — including tables, banquettes, over 300 chairs, and two dance floors — was kept ready in a warehouse.

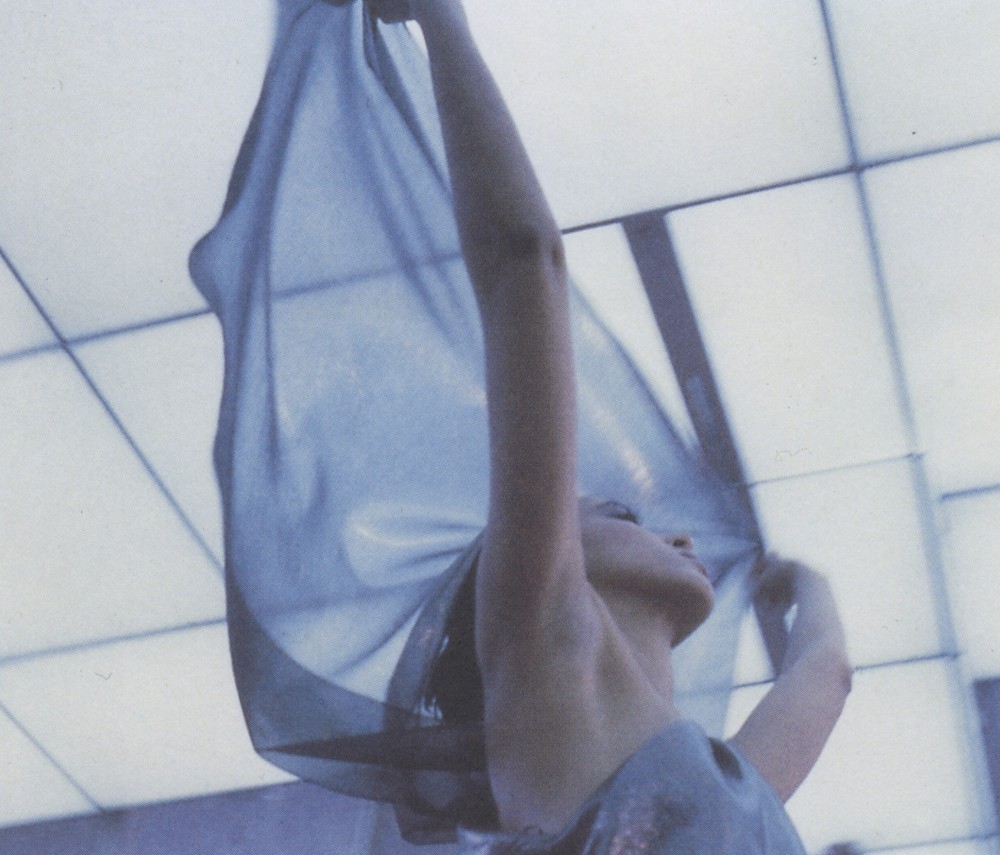

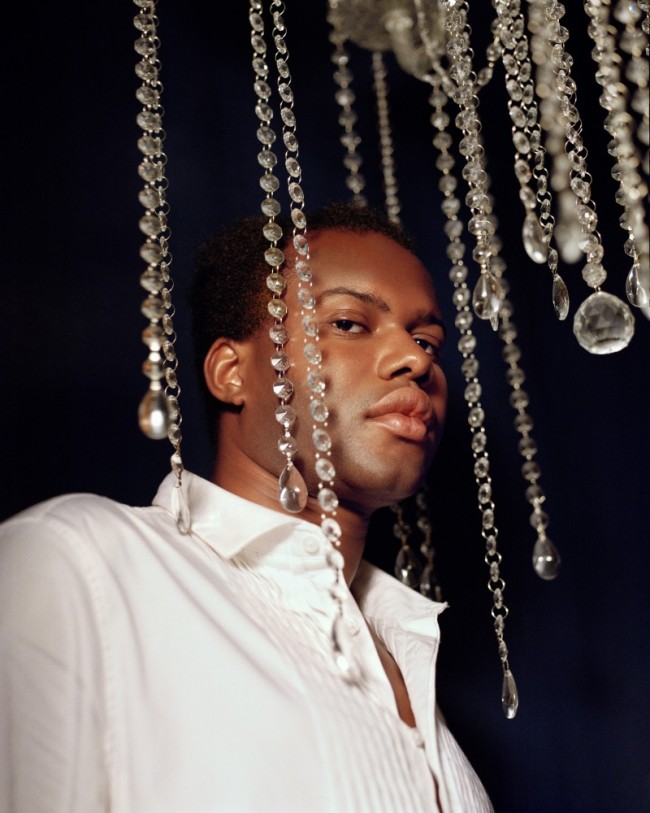

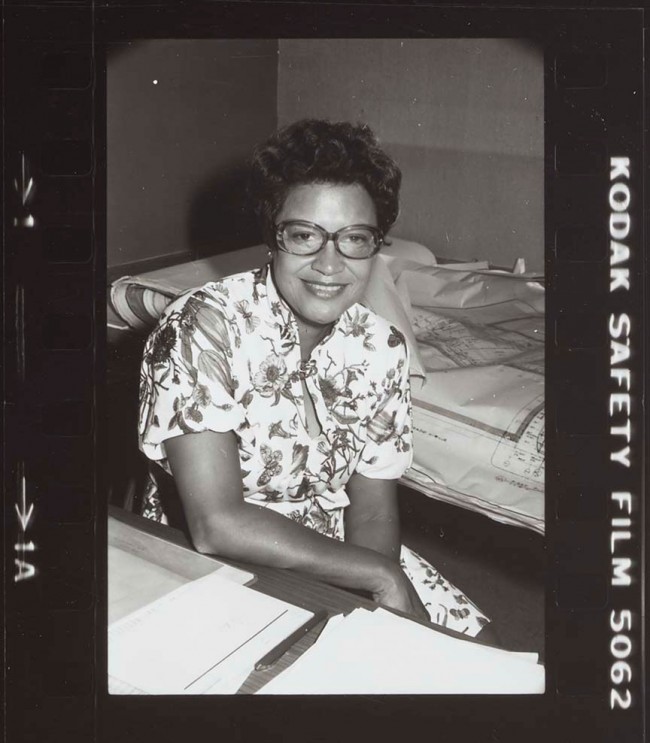

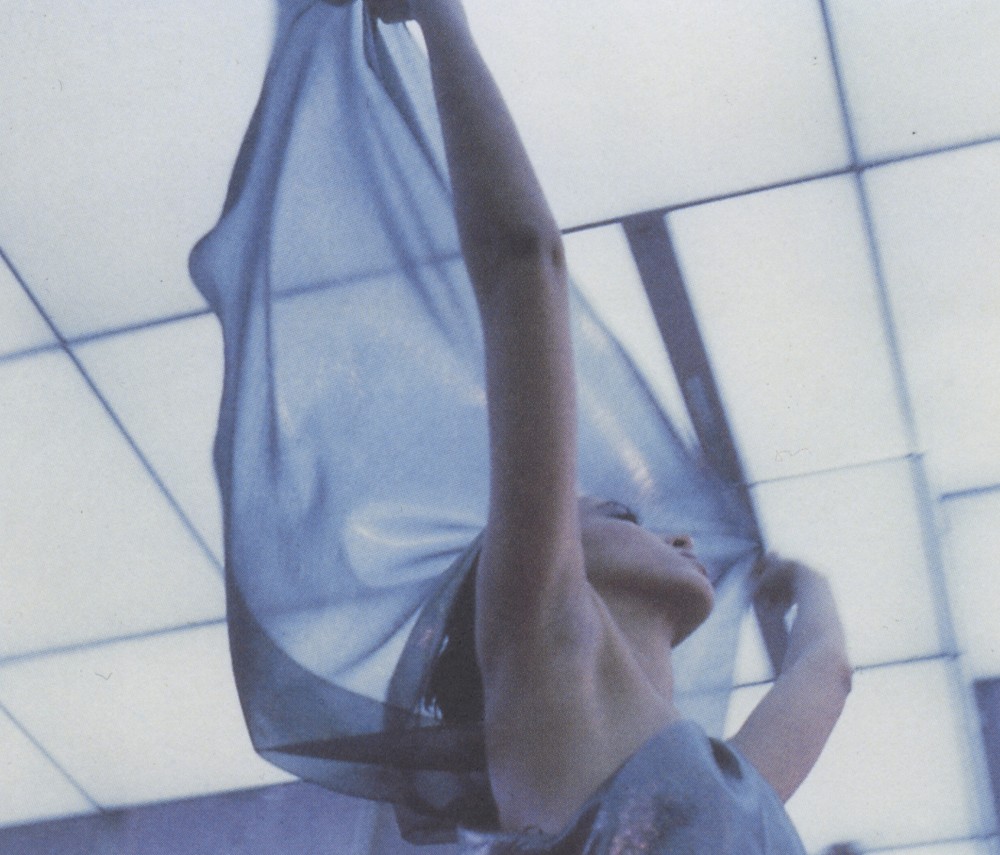

An exuberant Pat Cleveland, another Halston favorite, photographed against the showroom’s luminous frosted glass ceiling. © Scott Heiser, 1982

The premises in Olympic Tower took a total of nine months to realize and were officially opened in February of 1978 to the amazement of the industry, flabbergasted by their scale and opulence. Norton Simon’s David Mahoney joked, “We’ve got the most expensive loft in the city,” and chalked up its cost as a marketing outlay. Indeed, the premises did much to add to Halston’s clout and myth as only a modern hall of mirrors floating in the sky could. Seats at Olympic Tower fashion shows were in hot demand. One would always be sure to find sitting front row Halston’s infamous clique, which included Martha Graham, Liza Minnelli, Andy Warhol, and new addition Steve Rubell — the same Rubell who just a year prior to the completion of Olympic tower had opened Studio 54, the notorious nightclub that became the wellspring of 1970s New York hedonism. Tales of public sex, drugs, and all sorts of risqué behavior have made Studio 54 a legend in popular culture, and as Halston’s visits to the club grew ever more frequent, so his control over the company, and his status as America’s leading designer, grew shakier.

Whether at his desk at Olympic Tower, or at his home in the Paul Rudolph-designed townhouse on East 63rd street, cigarettes and orchids were a constant in Halston’s life. Photograph © Anton Perich

Much has been rumored about Halston’s drug use. And while he himself never publicly admitted it, and many of his closest friends and coworkers have adamantly denied they ever saw him use any, his behavior during the years at Olympic Tower was peculiar enough to lend verisimilitude to the rumors. Reported to have developed an addiction to cocaine, he became more caustic and temperamental in demeanor, arrived at the office later and later, and began to wear his trademark black sunglasses 24 hours a day. Those around him, faced with his constantly emotionless stare, were never sure if he heard them or if they were talking to their own reflection. Garbed in his habitual uniform of black turtleneck and sunglasses and silhouetted against the spires of St. Paul’s Cathedral, Halston was an intimidating sight, one that reportedly rendered a timid young marketing executive speechless with fright. This was a period plagued with daily drama: when Halston was brooding darkly at his table in the corner, employees knew they should stay away.

Halston Enterprises had built its business model on licensing. Traditionally, this had been a casual practice of fashion designers merely putting their names on a slew of generic products, but Halston insisted on total creative control that he refused to delegate. All licenses, from cosmetics, to blouses, to travel luggage, were designed by Halston. This maintained his integrity, but proved commercially disastrous as he became unable to meet the many deadlines. Most licensees eventually called it quits and happily let their contracts expire rather than deal with Halston’s increasingly difficult personality. The collections also began to lose their impressive quality and fashion critics and editors began lampooning his designs, accusing him of being repetitive and out of touch with the times. As the 1970s waned so did their look, which Halston had largely defined; losing ground to younger talent like Calvin Klein, the haughty designer perched in his glass tower began to appear increasingly dated. In those later years his everyday functioning became jeopardized, as John David Ridge, his assistant at the time, recounted to biographer Steven Gaines:

His hands would shake so much that he would have to point while I cut the fabric. Sometimes though, late at night, I’d see a little bit of brilliance come out. His ideas were brilliant. Sometimes he would be draping things and it would be wonderful. I’d think ‘Boy, what it must have been like before all this…’

But, after Halston had dismissed or bullied out the colleagues from the early years who could have stood up to him, his mood swings and ego would prove unstoppable. Sales of Halston’s custom and ready-to-wear lines dwindled, and in 1983 a desperate and unsuccessful attempt to launch a mass-market line for shopping- mall staple J.C. Penney put a profound distaste on the tongues of longtime luxury supporters like Bergdorf Goodman, who, on the announcement of the Penney deal, dropped his collection in its entirety. The designer was losing all the luster and glamour that only five years previously, after the move to Olympic tower, had seemed so assured.

Model and official Halstonette Karen Bjornson saunters down the runway during a fashion show at the designer’s mirrored 12,000-square-foot Olympic Tower showroom, c. 1979. © Anton Perich

Everything went into limbo that same year with the sale of Norton Simon Industries to Esmark, an even bigger conglomerate with even less understanding of Halston’s peculiar working methods. Unable to justify its extreme spending, which continued despite declining business, Halston Enterprises came under the scrutiny of Esmark executives who upon first visiting the showroom at Olympic Tower were astonished by the surreal scene and extravagance, likening it to The Wizard of Oz. A year later the situation would compound itself with the acquisition of Esmark by the even larger conglomerate Beatrice Foods; Halston’s larger-than-life reality was totally lost in a sea of Swiss Miss chocolate mix and Peter Pan peanut butter. The new management began to push Halston out of the company, and in 1984 locked him out of Olympic Tower, leaving Ridge to take over designing the lines. Halston remained contractually obligated to act as company figurehead, all the while battling Beatrice over legal rights to his name in the hope of reopening his house independently. In 1986 Beatrice was sold to BCI Holdings, an investment group who divested Halston Enterprises to cosmetic company Revlon. Though for a time it seemed Revlon was willing to bring Halston back, it never came to be, and Halston continued his legal battles and strenuous contract negotiations. In 1987 Ridge was proclaimed official designer of the line that had become a mere shadow of its former self. Halston’s social profile had also taken a hit, his appearance at a benefit dinner or fundraiser becoming a rare event. By 1989 he had become a total recluse. The days when he commanded the social elite and the fashion crowd were long behind him.

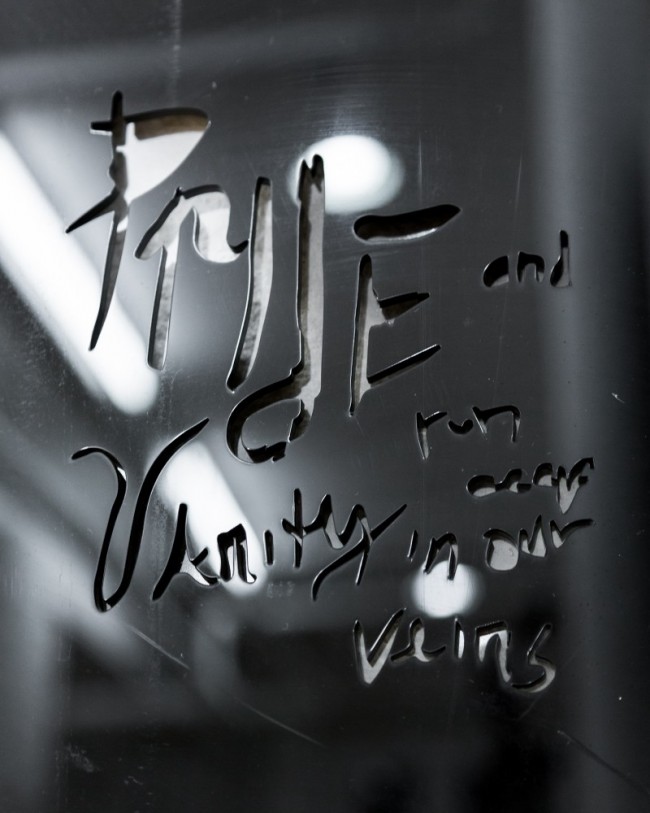

On March 26, 1990 it was announced on television news that Halston had died of AIDS-related lung cancer, one month short of his 58th birthday. He was one of the first high profile designers whose death was publicly acknowledged to have been caused by the epidemic. A dark cloud was cast over those who remained with Halston Enterprises, and any chance of salvaging the designer’s legacy died with him. There would be no return to Olympic Tower. In September of 1990, Revlon shut down all operations and closed Halston’s hall of mirrors permanently. Over the years the Halston name would be bought and sold, and many revivals attempted, but none of them would ever come close to having the impact Halston had made in the 1970s. His spectacular space in Olympic Tower would go down in fashion lore as an isolated phenomenon, a unique expression of the times, and of one man’s vision gone awry — his greatness and his downfall, expressed in panes of mirrored glass, in the endless reflections of dazzling light floating high in the sky.