SUNSETS: Scarpa’s Tomba Brion, Kahn’s Salk Institute, and Geomancy

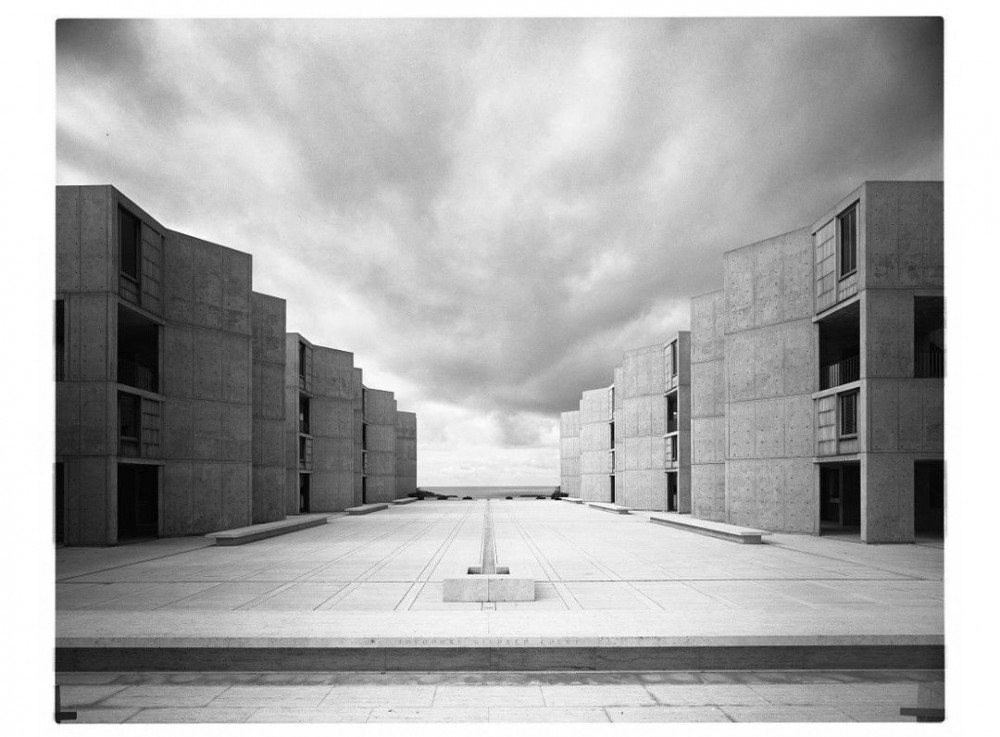

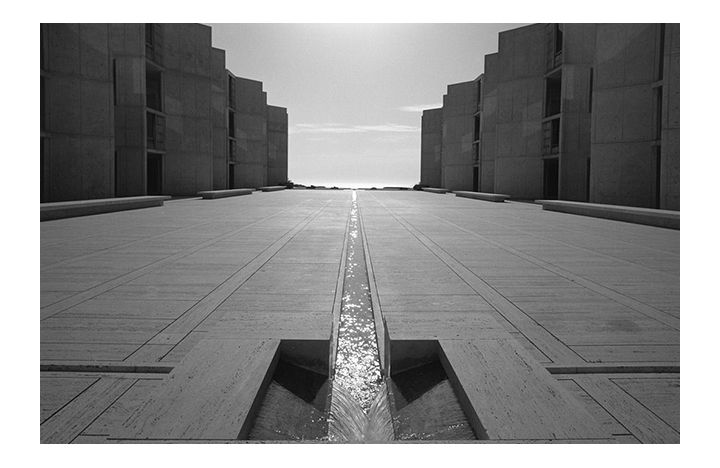

Louis Kahn’s Salk Institute. Photography by Elizabeth Daniels.

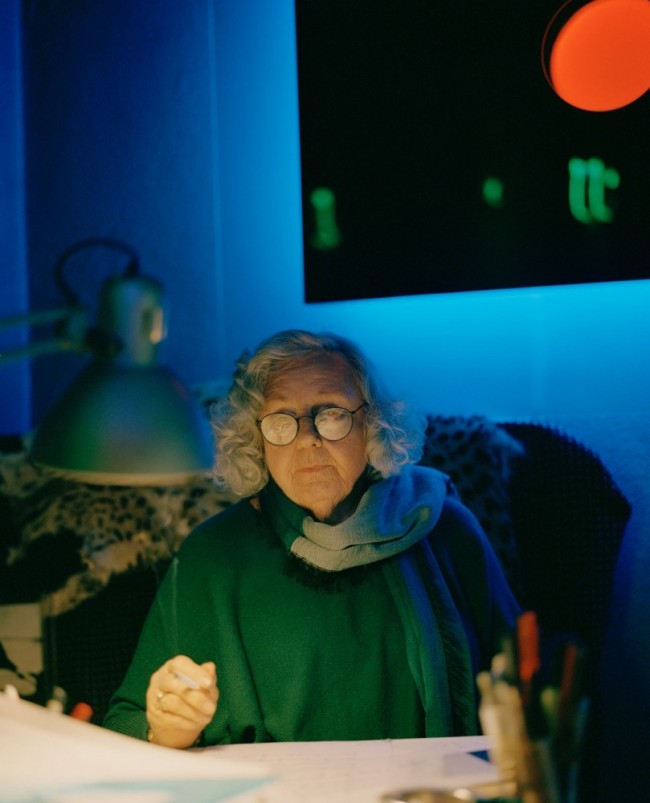

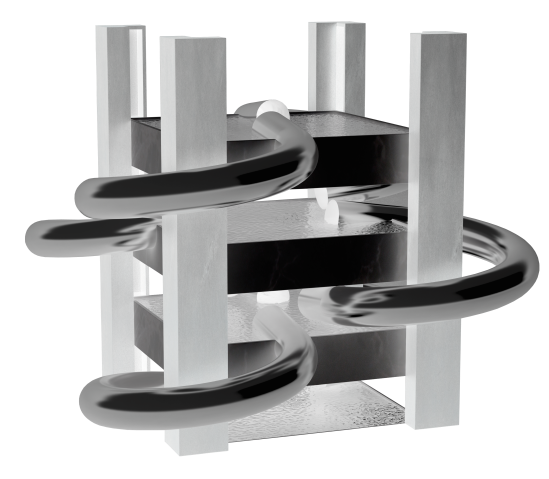

The meditation pavilion of Carlo Scarpa’s Tomba Brion (1968–78) stands in the southernmost corner of its L-shaped site, in a cemetery outside the Italian town of San Vito d’Altivole. Set in a lily pond, the pavilion is topped by a wooden canopy with a green metallic skirting, cleft in two about midway across the pavilion’s broad northern side. These two halves are linked by a curious brass fixture: a pair of demi-loops under a flat bridge, no more than a few inches wide. A little like a handle, but not quite, the fixture seems at first just one of those enchanting details that the Venice-based Scarpa was known to lavish upon his buildings.

-

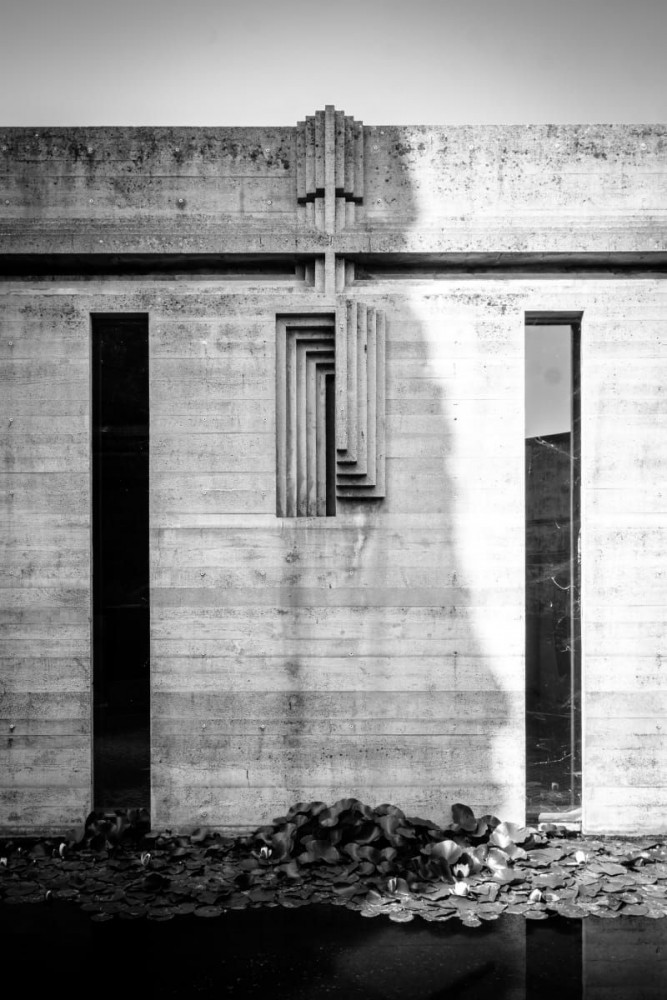

Entrance to Carlo Scarpa’s Tomba Brion, located in San Vito d'Altivole near Treviso, Italy. Photography by Jacopo Famularo.

-

Entrance detail of Carlo Scarpa’s Tomba Brion. Photography by Jacopo Famularo.

-

Entrance detail of Carlo Scarpa’s Tomba Brion. Photography by Jacopo Famularo.

When I visited the tomb for the first time last summer, I stood in the pavilion for a long while. It was a damp day in July, around 5:00 p.m., with a storm front lowering over the fields. The brass device in the pavilion comes up to about chest level. Yet, as I stood there, it seemed a natural focal point. I stooped to look through it — and in an instant the sun broke through the clouds, and the device framed a perfect view of the sunlight as it slanted crosswise through the cemetery, striking the lilies and the rain-slicked mosaic in the pond, and above all the huge concrete arc at the center of the complex. The bridge-like structure, which shelters the graves of the Brion family (founders of the electronics company Brionvega), lit up as though its edges concealed tubes of outrageous gold-red neon. The mysterious device, in that particular moment, was a viewfinder; the sun, gunpowder.

-

Entrance to Carlo Scarpa’s Tomba Brion. Photography by Jacopo Famularo.

-

Structural concrete detail of Carlo Scarpa’s Tomba Brion. Photography by Jacopo Famularo.

-

Outside Carlo Scarpa’s Tomba Brion. Photography by Jacopo Famularo.

“The detail is the adoration of Nature,” wrote Louis Kahn in 1974 — a line from a poem dedicated to his old friend Carlo Scarpa. Later that year, Kahn died suddenly; Scarpa followed him four years later, also suddenly. Neither man is now available to field questions as to what their intentions might have been in certain aspects of their work.

Carlo Scarpa’s Tomba Brion, located in San Vito d'Altivole near Treviso, Italy. Photography by Jacopo Famularo.

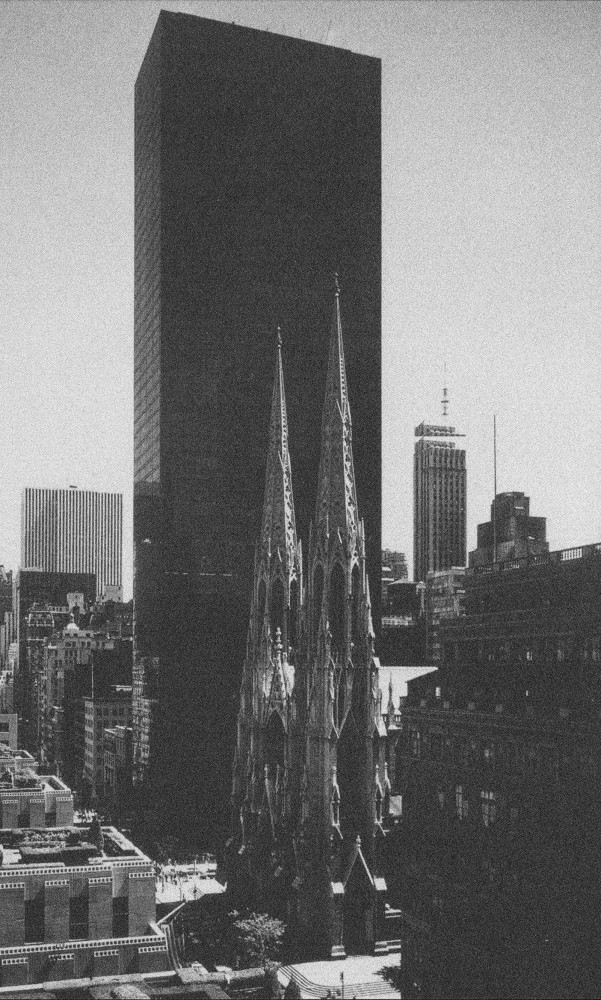

All architects are mindful of light, but there is a specific strain of buildings designed in deliberate relation to the sun and its yearly passage. The most celebrated is perhaps Stonehenge, its massive stones exactly framing the rising and setting sun on the summer and winter solstices. Other such calendar monuments, as old or older, can be found everywhere from Scotland to the Middle East. Similar phenomena appear in modern times — albeit typically by accident, as in the case of New York’s semi-annual “Manhattanhenge,” when the sun sets exactly along the line of the island’s lateral streets.

So is it possible Scarpa really intended the Brion pavilion’s brass fixture as opera glasses for a seasonal solar light show? Probably not… or at least not in the way it seemed to me. In any case, why was I so convinced that what I saw must have been, in some way, deliberate? There is a scene in one of the Indiana Jones films in which the title character arrives as planned at the steps of some ancient temple at the exact moment when the sun strikes the designated spot on an archaic stone relief, revealing the secret entrance to a lost tomb. At Stonehenge, in 1985, a pitched battle took place between police and hordes of neo-pagans who descended on the complex at the summer solstice; access to the site has since been strictly controlled. There is something irresistibly appealing about the idea of an architecture of the sun, and of being there to see it activated, as if some kind of magic might unfold.

-

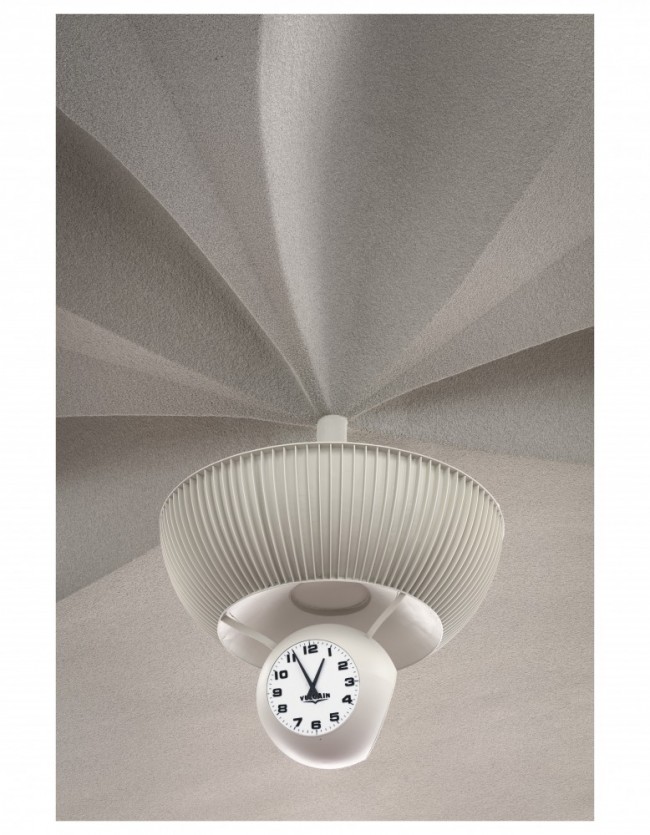

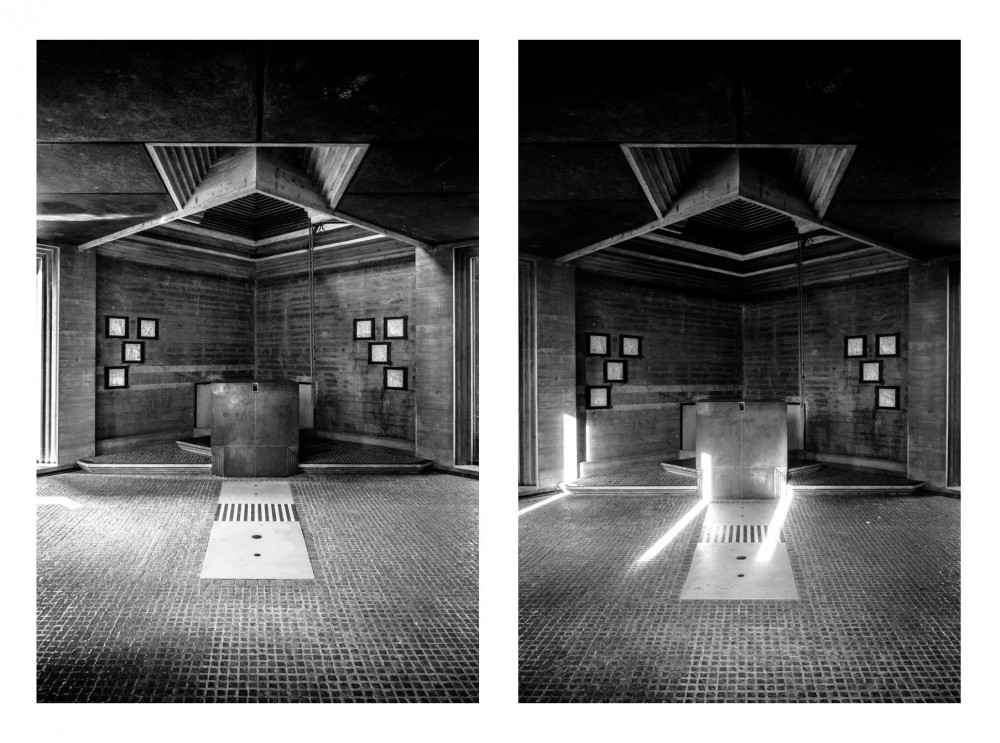

Chapel ceiling detail of Carlo Scarpa’s Tomba Brion. Photography by Jacopo Famularo.

-

Outside Carlo Scarpa’s Tomba Brion. Photography by Jacopo Famularo.

-

The altar in Carlo Scarpa’s Tomba Brion. Photography by Jacopo Famularo.

There is some suggestion that Scarpa did take the sun’s path into account when he designed aspects of the tomb. The complex’s most important structure is not the pavilion, but the archway underneath which the Brions themselves are buried, located exactly where the two arms of the L meet. The burial spot, rectangular in plan, might be expected to be orientated rectilinearly to the L, or at least (as is the case with the nearby chapel) along the cardinal compass points; instead, the tomb and only the tomb is rotated, lying along an axis approximately 10 degrees short of true northwest. Judging from the available maps — and from the Internet’s most popular solar-path software — the tomb is actually pointed towards nearly the exact spot where the sun goes down on the longest day of the year, which falls between June 20 and 22. Had I been there a scant two weeks earlier, at around 9:00 p.m., I might have looked north through the pavilion fixture to see the funerary monument glowing in even greater splendor.

Notwithstanding the purported accuracy of “suncalc.org,” it might be difficult to prove all this: visiting hours at the Tomba Brion seemingly vary on the whims of local authorities, and it may well be closed at 9:00 p.m. on a summer night. Still, the possibility makes one wonder: what other modern monuments are hiding comparable, equinox-related secrets?

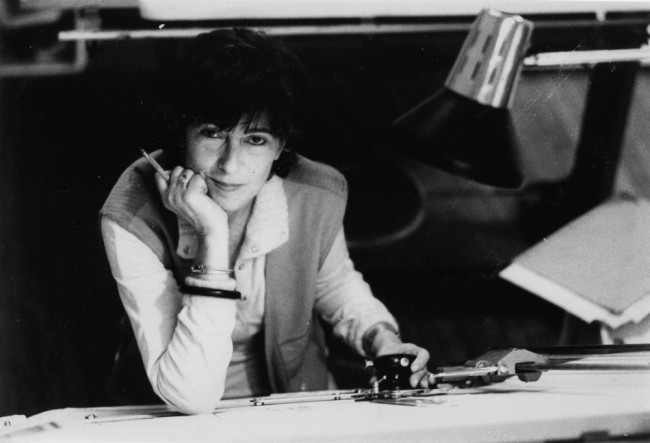

Louis Kahn’s Salk Institute. Photography by Ezra Stoller. ©Ezra Stoller/Esto

Immediately I thought of Scarpa’s old friend Kahn, and his Salk Institute in La Jolla, California (1959–65). Enjoying an unobstructed view to the Pacific Ocean, the complex, with its two rows of serrated concrete towers, is etched down the middle by a water feature (suggested to Kahn by Luis Barragán), tracing a perfect line due west to the horizon. Surely, whatever day the sun descends exactly along the western azimuth, it must make for a pretty stirring scene.

As with Manhattanhenge, “Salkhenge” (to coin a phrase) occurs twice annually. The first date, approximately September 22, coincides with the fall equinox. The second date, on or about March 17, lines up with the spring equilux, when night and day are of equal length. But that second date rang another, uncanny, bell with me: March 17, 1974, was the exact day Louis Kahn died. An eerie — one might say cosmic — coincidence, and another architectural sunset worth seeing.

Text by Ian Volner.

Ian Volner is a Manhattan-based writer and frequent PIN–UP contributor whose work has also been published in Harper’s, The Wall Street Journal, and The New Republic. His book The Great Great Wall (Abrams Press) was published in 2019.

Photography by Elizabeth Daniels, Jacopo Famularo, and Ezra Stoller.

Taken from PIN–UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.