INTERVIEW: Francis Kéré on Building in Europe and In Africa and His Ethic Of Simplicity

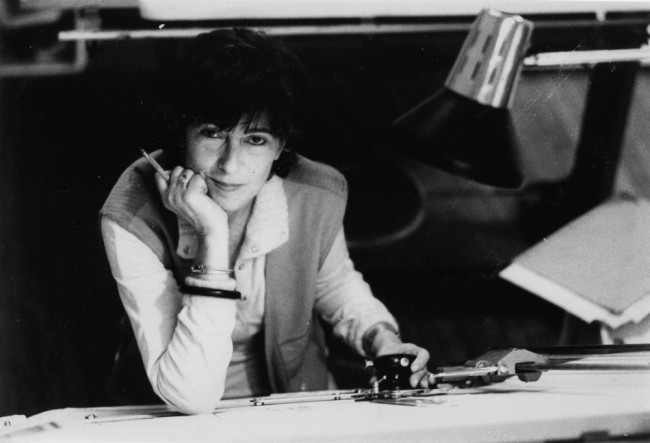

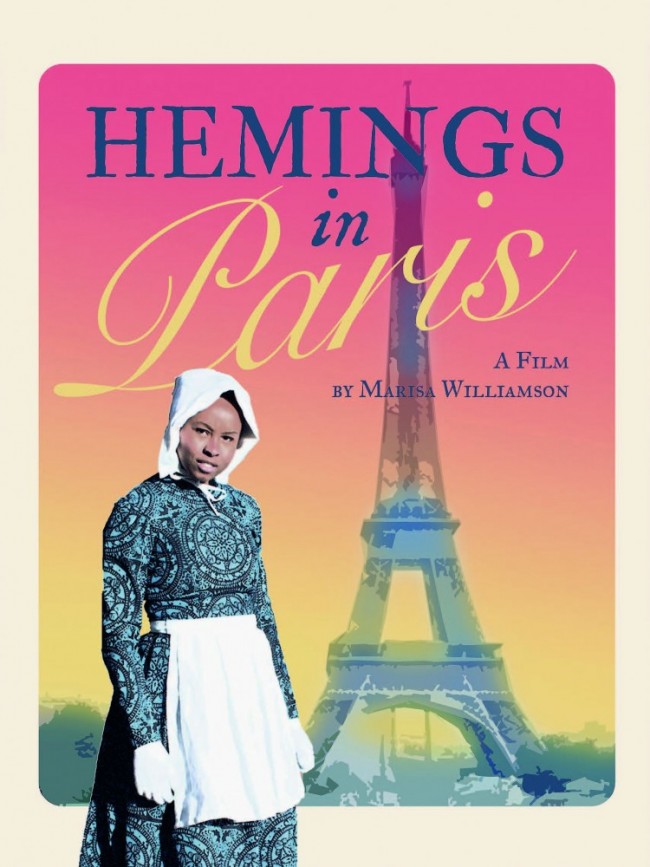

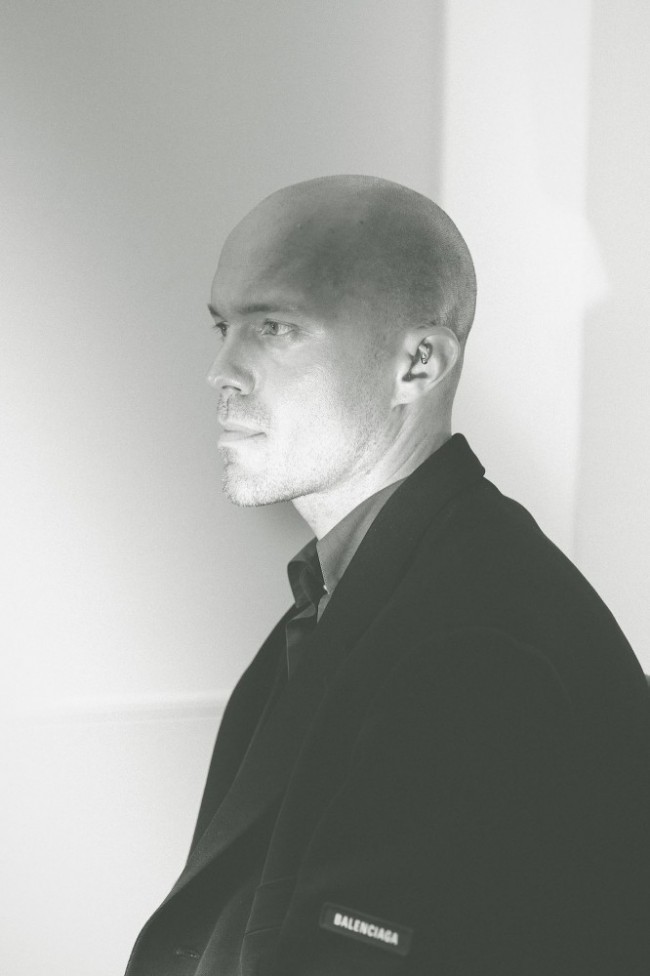

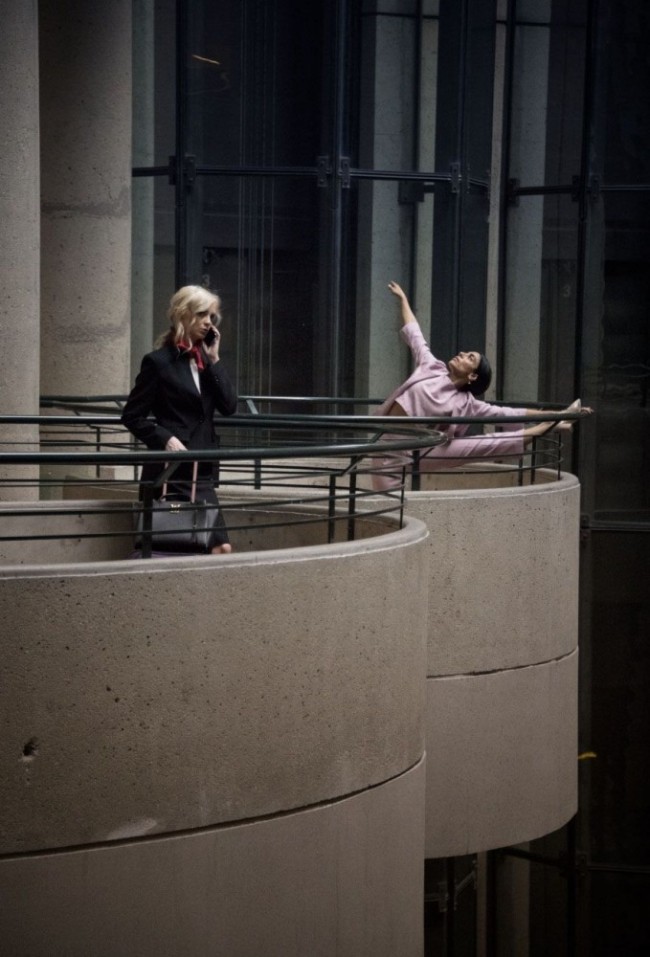

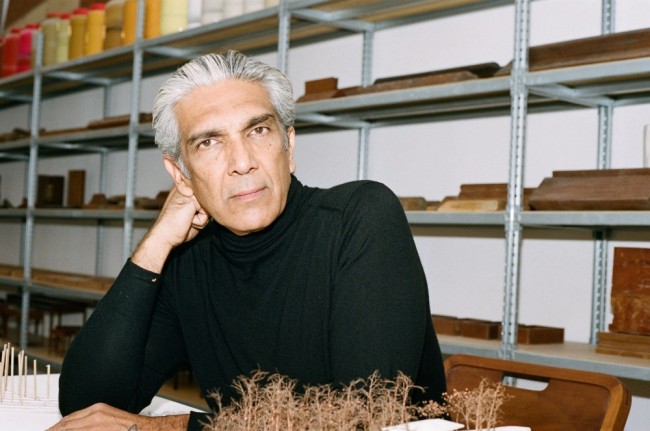

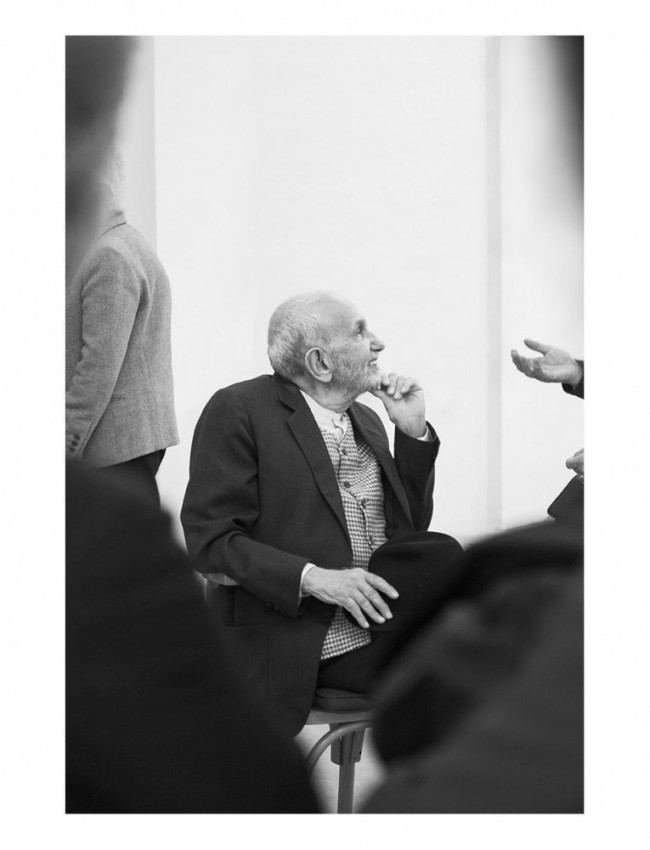

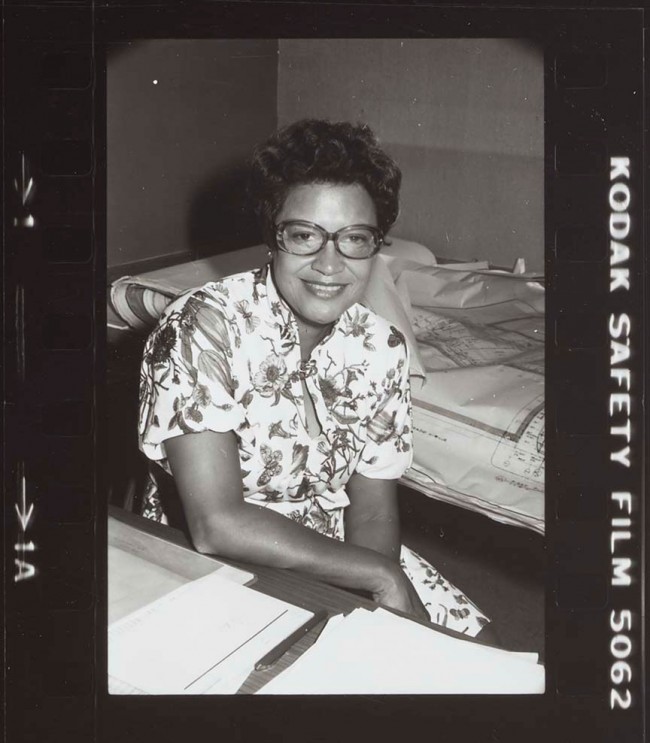

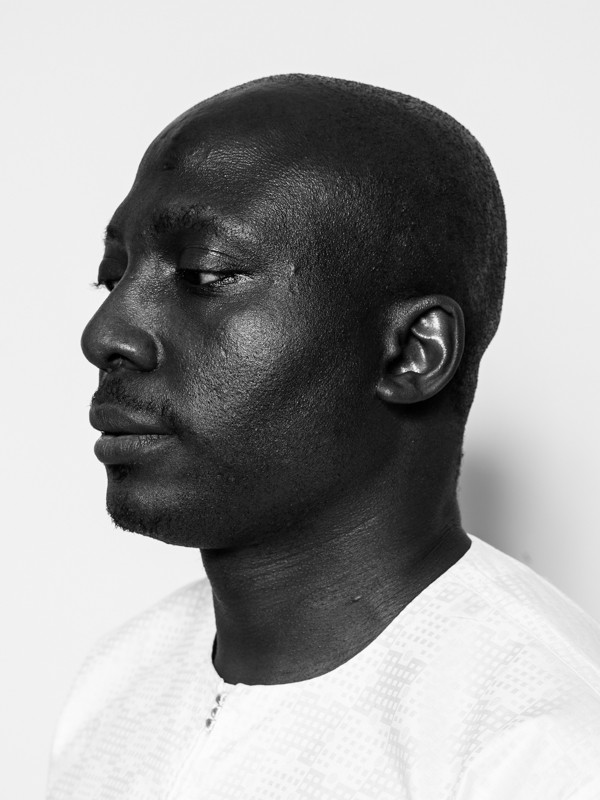

Francis Kéré photographed by Paul Hutchinson for PIN–UP 28.

While still a student at Berlin’s Technical University in the early 2000s, Diébédo Francis Kéré designed the first ever primary school in Gando, his home village in Burkina Faso, a landlocked nation in West Africa. Built with the help of villagers utilizing local materials, the school became a symbol of community pride and also won Kéré the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2004, the same year he completed his architecture degree. Applying his contextual approach wherever he goes, Kéré prioritizes efficiency, simplicity, and the value of the building to those who will use and experience it. Today, looking back on two decades of work, Kéré almost seems surprised at the position he’s reached — a world-renowned architect who has built extensively in Africa and Europe, who was awarded the 2009 Global Award for Sustainable Architecture, and who designed the 2017 Serpentine Pavilion. He is also currently working on two different national parliament buildings in West Africa as well as his first major project in Germany: a campus tower at Munich’s Technical University, where he also teaches. Trained as a carpenter, Kéré first came to Berlin wanting to learn something about building that he could take back to his community to help improve the way they lived. Thirty years later, the humble 55-year-old has achieved all that and more. PIN–UP paid him a visit in his Berlin-Kreuzberg studio.

Shumi Bose: You just returned from Porto-Novo in Benin.

Francis Kéré: Yes, we’re working on the new parliament there. The project started in 2018, through a competition. Shortly before Christmas last year, we got a call to propose an updated design. We only had four weeks to do it. It was intense! But that’s our job. In the last couple of years, I’ve been preparing the studio to have the capacity to react quickly.

What is your vision for the Benin parliament?

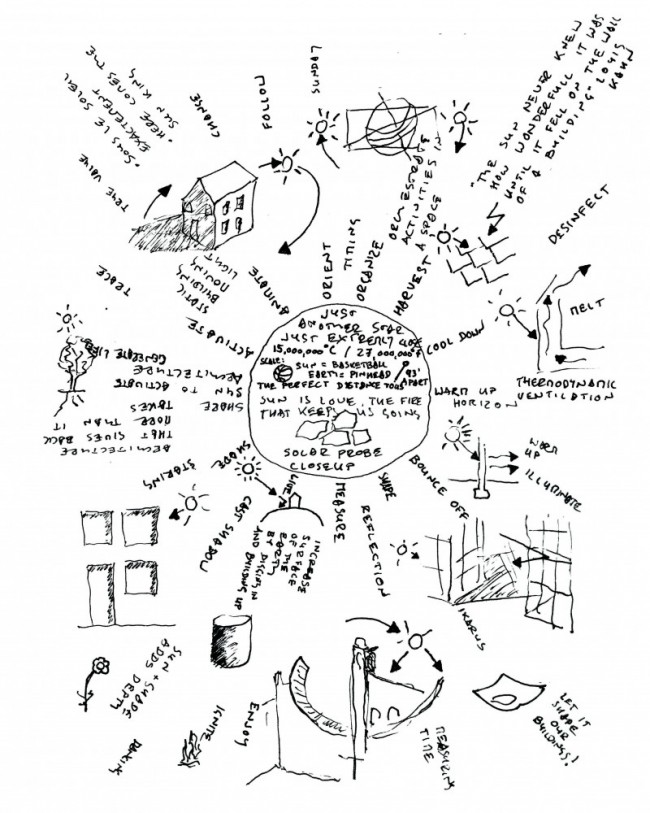

We want the building to represent the traditions of Africa. The way debate was conducted in the past was to sit under a big tree, where everyone can see the gathering and contribute to the discussion. At the same time, sitting under a tree is a traditional meeting place for the elders — the wisest gather to discuss the destiny of a community, of a tribe, of a people. So we want to build a big palaver tree — we physically wrote that into our sketches. For me, it is about the tree as a symbol, a tree with the shadow that embraces you. The site is next to a very ancient city, which helped support my idea of learning from the past to develop for the future.

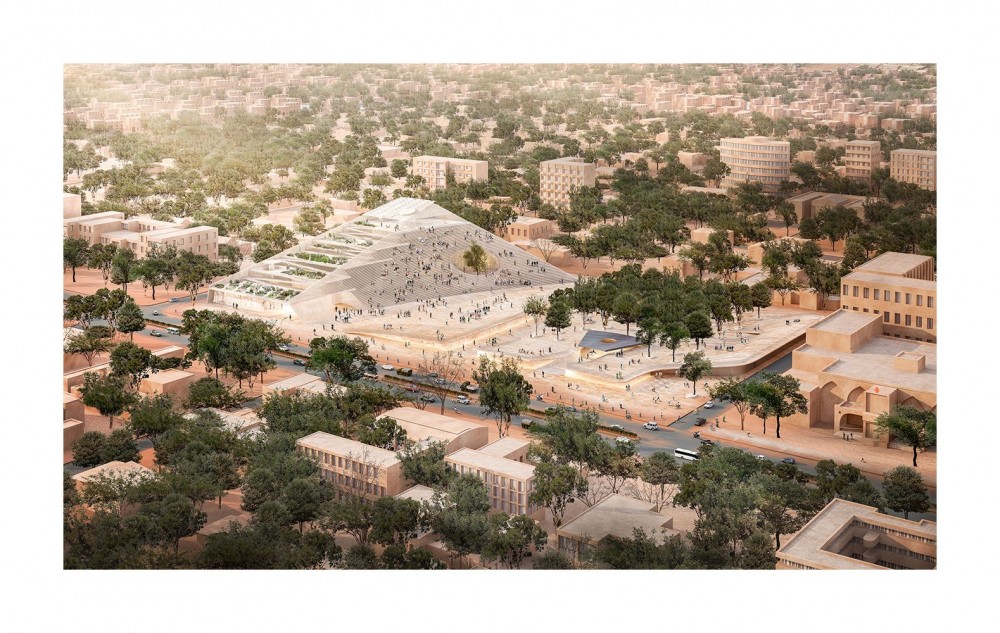

Let’s talk about a more speculative vision — your pyramid in Ouagadougou.

Ah yes, the parliament house for Burkina Faso. In 2014 there was a sort of revolution. The president at that time wanted to change the constitution and make himself president for life; a mob overran the parliament house and burned it down. I was busy doing my own thing, then one day I was contacted by a self-organized committee — members included intellectuals, musicians, artists, a few politicians, and also simply activists — that called to say, “We want to rebuild the parliament house and we want you to propose a design that is transparent, accessible, visionary, and sustainable.” They wanted it to feel open to the public, welcoming. So I used this idea of a pyramid. I wanted to design the project so that the people can access it at any time, and even get up on the roof. It was partly inspired by the renovation of the Reichstag in Berlin (Foster + Partners, 1999), where you can access the roof. It’s symbolic, saying that the building is open, the public can watch their representatives in action — you can see if they’re doing their work, and they know who they are serving. Another key element is to raise people’s perspectives, literally, since Ouagadougou is flat and very low, mostly one-story buildings. I want to offer a sense of pride for the people — it’s important for them to see the capital differently, to be able to appreciate it. I want the building to become the most public, and permanently public, space in Burkina Faso. There is no public space really like that.

Rendering of the Parliament Building of the National Assembly of Burkina Faso. Courtesy Kéré Architecture.

Can you tell me about the garden inside the parliament?

The idea is that every region (in Burkina Faso) would come and create a piece of landscape, based on agricultural produce. The garden wouldn’t just be contemplative, but also educational. To teach other regions how they grow, so it will make them one nation and unite all the different regions. Here you see the metaphor of the tree again. In this case, the tree was embedded in the parliament, as an informal meeting point. These metaphors will help us to recall our own origins, rather than replicating a national assembly from France, which is often the case. My hope was that the next time there’s a revolution in the country — and I’m sure it will come soon, because we have very high youth unemployment — they won’t want to burn it down. If it can become a truly public space.

Do you think it will be realized?

When I travel to Burkina, I sometimes see the prime minister or our foreign minister on the plane. There are always all these questions, “Mr. Kéré, Mr. Kéré, what about our parliament house?” I say, “It’s not me making the decisions, it’s you.” (Laughs.) There are some issues with the proposed plot of land. They suggested that we could change the site to somewhere outside the city. It makes no sense so I refused. But the project is still underway, and even earlier this year they were trying to organize a meeting with the new president. But sometimes projects don’t need to be realized, you know? The inspiration is food for creativity. We need visionary ideas. And if they’re coming from our people, the changes that happen are unbelievable. For myself, it’s amazing to see the reactions to this project.

Left: The shelves at Francis Kéré’s Berlin studio are full of study models and material samples: (top right) a massing model of the Kamwokya Playground and Community Center in Kampala, Uganda, currently under construction; (bottom right) a wooden tool used in Burkina Faso to manually flatten earth.

Right: A model of Benin’s new National Assembly in the capital Porto-Novo, designed by Francis Kéré. For this project, still in the design stage, the principal reference is the Palaver tree and the African tradition of leaders meeting beneath it to debate and discuss the destiny of their community. The architect often finds inspiration in trees and cultural traditions associated with them. The model is sitting on a pedestal made from tree branches similar to the construction of Kéré’s 2019 pavilion, Xylem, at the Tippet Rise Art Center in Fishtail, Montana.

Photography by Paul Hutchinson for PIN-UP 28.

How many of your projects are speculative like that?

We don’t usually do competitions if we aren’t invited. And we usually don’t do projects that are completely speculative. But when they called me for the parliament house in Ouagadougou, there was no way I could say no. If I had, they might have thought I was too detached, that I don’t care. But I thought that if I suggested that the people climb on the top of the parliament, they would say, “No, no, no, no. We don’t want that.” Some people involved with the project warned me: “No leader will accept a project like this, not just in Burkina, but in all of Africa.” Then I had to present it to the parliament and the president and, to my surprise, he only said, “Mr. Kéré, we have to talk. You have to reduce the size.” I was really shocked.

What strikes me about what you just told me is how often we doubt ourselves, even as a nation or a people. You didn’t think your design would be accepted. Particularly in former colonial countries, there’s often a nagging doubt as to whether anything autonomous can be truly successful. I think you’re right to provide something visionary. You have to inspire people for anything to happen at all.

Yes, yes, yes. Inspiration is for innovation and for design. It acts the same way as food. Food is for creativity.

Left: Study models in Francis Kéré’s Berlin studio: (upper shelf, left) Xylem, a visitor pavilion at the Tippet Rise Art Center in Fishtail, Montana, completed in 2019; (upper shelf, right) the Thomas Sankara Memorial in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, currently in the design stage; (bottom shelf, left) the Burkina Faso National Assembly in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, currently in the design stage; (bottom shelf, right) seating elements for a wedding pavilion in Bangalore, India, currently under construction.

Right: Study models for Sarbalé Ke (2019), a cluster of colorful pavilions Kéré designed for Coachella music festival.

Photography by Paul Hutchinson for PIN-UP 28.

What do you think about the growing relationship between China and Africa?

In Europe, some commentators seem skeptical, concerned there is a weakening of African ownership over the developing infrastructure. From my experience, Africans see the West as a great example. They try to do everything like the West. But if you look at the West’s relationship with Africa over the centuries, you would have to admit the continent is still missing a lot of infrastructure that it needs. Then you have to start asking yourself some questions. You start to believe what some people are saying: that the West has no interest in seeing Africa develop. The second thing is, of course, paternalism. The West thinks that the best path for Africa is to do things carefully. It’s like a dad or mom with their kids. You should allow the kids to grow up, to make mistakes, to learn from them. You cannot be controlling. Another issue is that the population in Africa is growing incredibly fast. People need technicians and governments to support them in building infrastructure. Most of the time there is no available expertise. Professionals from the West are very expensive, and then there are cases where partners from the West don’t respond to the request, but rather try to change the project. This situation is pushing African leaders to deal more and more with China. Chinese partners come, often with the money, expertise, and professionals. So I mean, that is just a fact. It’s a pity, but this is the reality.

Why do you say it’s a pity?

It’s a pity that in making that criticism of China’s relationship with Africa, people don’t dig deeper. They just say it might be bad to work with China, instead of asking why the situation is like this. I’m striving to do things myself. I just came back from visiting the Royal Baths at Meroë, in Sudan. This site in the middle of Africa is more than 2,000 years old. (Kéré Architecture is building a protective shelter for the ruins.) When you see that you can imagine what is possible in this continent. We have to allow for a free African imagination. There is a big need for infrastructure, and one of the strongest partners for that now is China.

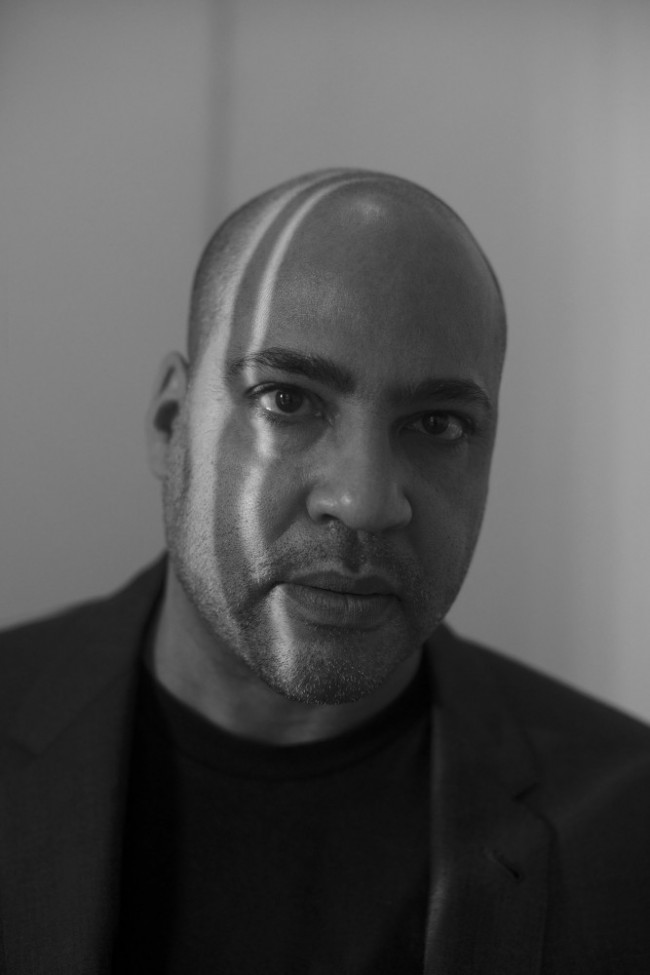

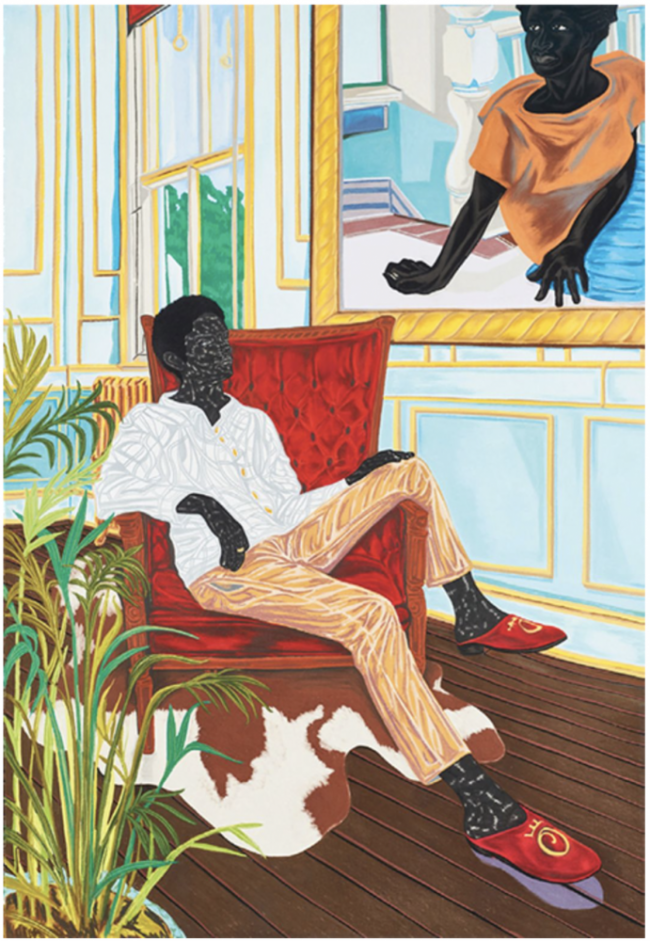

Francis Kéré photographed by Paul Hutchinson for PIN–UP 28.

What buildings inspired you as a young man? Which ones were your “food?”

When I started studying, I had no knowledge about the history of architecture. I wanted to gain knowledge, to be able to develop things in my own village. I just wanted to build. Of course, when I started to study, I discovered the real world of architecture. When you study in Berlin, you will face the great Mies van der Rohe. I really like the art of rationalism he applied — so efficient, so simple, very clear to understand. Later on, I traveled to India and discovered Louis Khan’s Indian Institute of Management (Ahmedabad, 1974), for which he used local brick. For me, it was really an eyeopener.

What was it about that building?

Kahn’s adaptation to the place, the use of brick, the simplicity — but then the complexity, at the same time. So Khan and Mies for sure, they were really key for my own work. And later on I was looking at architects who were doing very simple things, very small buildings. That’s how I came to know the work of Glenn Murcutt. The simplicity of his buildings impressed me so much, because it was different from all the others. I wanted to do something simple, something rational, very useful for my people. I also recently visited Taliesin West, Frank Lloyd Wright’s place. As a student, I couldn’t reach Frank Lloyd Wright through his drawings. If you look at the plan, it’s a lot of lines, very complicated to my eyes. But then I went to see his site at Taliesin, seeing how he used local rocks to create all of this. I thought, “Wow. Why didn’t I visit this place before I started to build? I would have been much more confident about my own work.” Because there are a lot of parallels between our work, the way we study the local rock, trying to use it, using different materials to see how they work.

When you were a student, did you imagine to be in the position you’re in today?

I am really surprised with what happened and who I am today in the professional world of architecture. It was never my intention. I didn’t even want to graduate. My professor, Peter Herrle, had to convince me to complete my degree. I was focused on simplicity, and saw that I could go out and build by myself. And indeed that is how I started to build, without engineers. Of course, I had the support of a lot of professors. But in the end, I had to go and do it.

There is a sense of pragmatism in your office: modeling, making, the rational handling of materials. I think you said, “It doesn’t matter what the problem is, you show me the problem and I will fix it.”

Yes, exactly. That is my way. Just fixing and finding solutions. This is what I try to do — to serve.

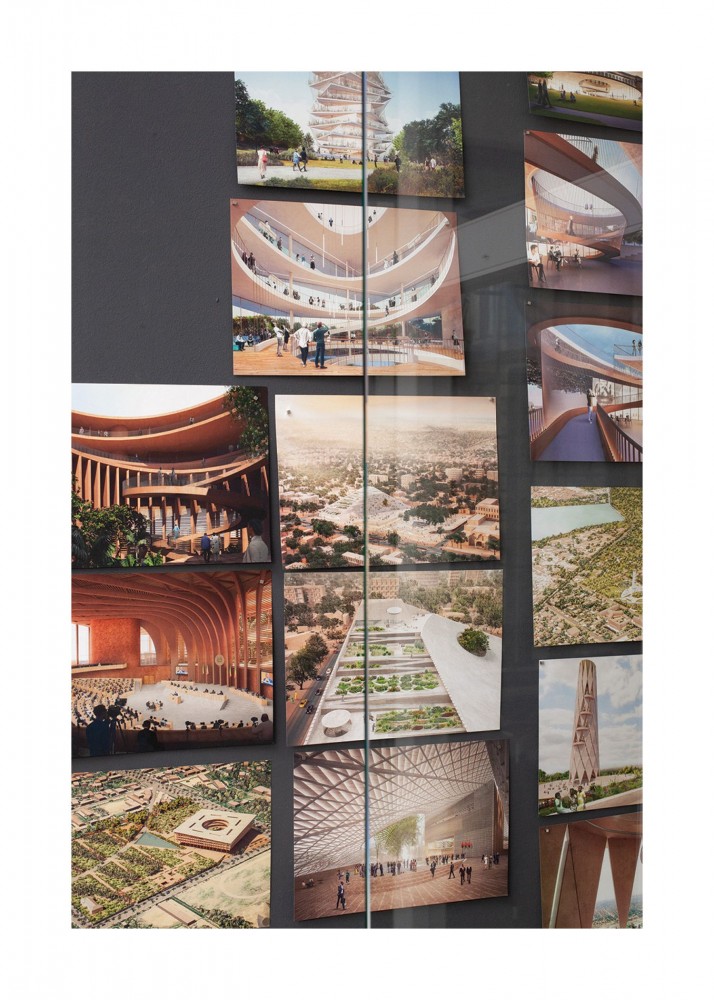

Renders pinned up on the wall at Francis Kéré’s Berlin studio show several projects all currently in the design stage: (top) the TUM Tower, commissioned by the Technical University Munich where Kéré is also a professor; (left) the National Assembly of Benin in the West African nation’s capital Porto-Novo; (center) a new national assembly in Ouagadougou the capital of Kéré’s native Burkina Faso, to replace the parliament house destroyed during the 2014 revolution; and (bottom right corner) the Thomas Sankara Memorial also in Ouagadougou.

Photography by Paul Hutchinson for PIN-UP 28.

That is quite different from, as you just said, the position that you’re in now — a famous, celebrated architect from Africa. Do people expect you to take on a more political role as a representative of “African architecture?”

I do the work. If this work is seen as a representation of the continent, then I’m happy, but it’s not me. If you had seen me in Meroë, in village clothes, you would have been surprised. I was so happy cutting woods with the workers, because I was trained as a carpenter. At the beginning, they were really surprised too. Suddenly they started to see me differently, because we are all makers. That’s also why it was good for me to be in Germany. It was technology and the knowledge to make things that I thought I could find here.

When did you come to Berlin?

Oh, I came to Berlin just before the wall fell. I was a simple carpenter. I went to night school for five years to finish my high-school degree, then started my architectural studies in 1995. My mission was to go back to school, study architecture very quick, and then return to Burkina. That was my main concern.

So that’s 30 years ago now. How did you start your office?

The office started in my kitchen. I was almost living in the kitchen to draw and doodle. My partner at that time would complain. Like every architect, probably, I would come home in the evening and go to the kitchen, sitting and working, trying to draw. And then came the time when I bought my own computer. I was getting friends to come over to fix it, even late at night. In 2005, I moved the office out of the kitchen, to save the peace of the family. (Laughs.) I started to work, sometimes alone, or with an intern. My students, or friends of mine who graduated at the same time, would come and go. Some tried to stay longer, but there were no resources to pay them. I was still dealing with the Gando Primary School project in Africa. They would come to support it, but when it was time to go and earn money, they had to leave. They had to find their way in life. Then, in 2006, I started to have “real” jobs. The Dano Secondary School (Burkina Faso, completed 2007) was the very first project that we got. In 2008, the Aga Khan commissioned me to build a national park (the National Park of Mali, Bamako, completed in 2010 and commissioned by the Aga Khan Development Network and the Aga Khan Trust for Culture). In 2009, in parallel, I started the Opera Village in Burkina Faso (an ongoing project developed in collaboration with the late German artist and director Christoph Schlingensief). Slowly, things started to grow, and I was able to keep some people for more than one year. But then I’d train people — because the way we work is very different from what they teach in architecture school — but sadly not be able to pay enough, so they’d eventually leave again. Now we are about 12 to 16 architects and two paid interns at any one time. And we seem to be growing.

What do you mean when you say that what people train for in school is not what you do?

The kind of work we do, in the kind of environments where we work, needs a very special architecture. We use very different techniques, sometimes very old techniques, that have to be adapted because of special conditions, materiality, site specificity, climate, and so on. In design school, you don’t normally learn to adapt all of this so constantly, and then also to deal with people at the same time. Not everyone is able to do that.

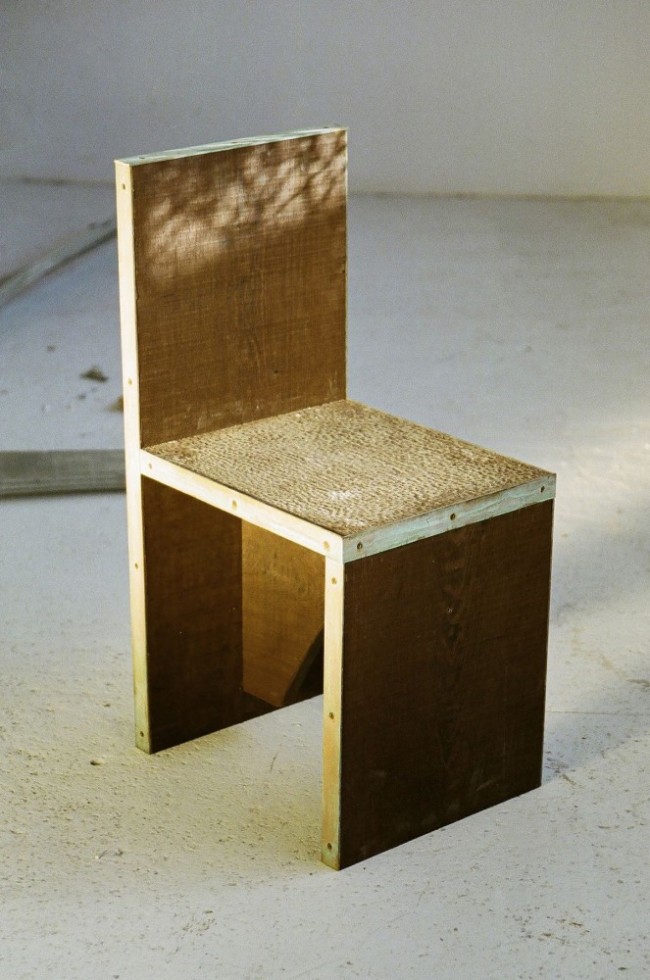

Whether he’s on site or in his studio in Berlin-Kreuzberg, Francis Kéré favors a hands-on approach with materials and models. As a young man Kéré chose to study in Germany because he had come to associate it with technology and innovation. As a carpenter in Burkina Faso, he’d noticed all the best tools he worked with were made in Germany.

Photography by Paul Hutchinson for PIN-UP 28.

Perhaps the most difficult thing for the architects working with you is dealing with another culture.

It’s very difficult. We’re not trained as psychologists, and schools don’t tell you how to deal with people. But it’s the basis of my work to push people to participate in a project, to convince a community to work, to carry stone and rocks to make foundations, to make bricks, to make a school.

Is sustainability a strong concern in your office?

I think that in architecture today, everyone wants to demonstrate that their work is “sustainable.” For me, it’s just what I do and have always done. I try to use the material in the most efficient way, I try to see what is available on site, to discuss and look together with the client for the best material for the project. Then of course we think about designing in a way that doesn’t consume a lot of energy, for heating and cooling.

If “sustainability” is not a label you’d consciously wear, are there any others that people have attributed to you and which have made you think, “Wait a minute! That’s not quite what I was trying to do?”

Yeah, it happens all the time. There is a danger that people want to put you in a corner. They’ll say, “Oh, it’s the mud architect.” If I use mud, it is through working with mud specialists. If you check my buildings, you’ll see I don’t only build with mud, I’m an architect who looks every time at a given project, finds what is most available on site in that country, and responds in the most efficient way to the client’s brief. And similarly, if someone comes so far to study architecture in Germany, and loves Mies, loves Kahn, admires Frank Lloyd Wright, is impressed by the intellectual capacity of Le Corbusier, and many, many more, you cannot just reduce him or her to an ethnic architect.

Rendering of the Campus Tower at Munich’s Technical University. Courtesy Kéré Architecture.

Let’s talk about your first major project in Germany, the tower at the Technical University in Munich. I don’t think it’s a design people would expect from you.

Yeah, true. First, the height — people wouldn’t expect that from me. But I’m sure the building will be a catalyst, a new way to connect the different institutions and departments within the university. It’s a very demanding project. How can I be honest to myself at this scale and in this place? The purpose is to create a sort of gathering place and landmark for students, for alumni, for new arrivals, but also for the different departments of the university. There is a need for identification and orientation. The schools have been growing in an organic way, so when you arrive, there’s no central place within the campus. I looked into Bavarian traditions, and I found out about the Maibaum, the maypole that’s set up every spring in a central place in the village. Everyone comes to celebrate around it. Friends in London told me that they recognized a similar tradition. I wanted to design a sort of symbolical Maibaum that will rotate and attract, like it has gravitational force.

The galleries are placed radially around the building so that the views reach out in all directions across the campus.

Exactly. So everyone feels part of it, everyone feels connected to each other. And I wanted a participatory way of working, like what I’m trying in Gando. I would like to open the door to other departments in the university, and if someone has an idea, for example about an intelligent façade that can react to the climate, then it is welcome.

Left: A model of the Technical University of Munich Tower, Francis Kéré’s first major project in Germany, currently in the design stage.

Right: Kéré has many projects in Africa and spends much of his time there, but for the past 30 years, his primary residence has been in Germany. He first emigrated from his native Burkina Faso to study in Berlin right before the fall of the Wall. At his longtime studio in Berlin-Kreuzberg, study models and material samples pack the shelves.

Photography by Paul Hutchinson for PIN-UP 28.

We talked a little bit about some of the Modern masters who were inspirational for you. Are there any contemporary practitioners you admire?

Yes! Today there are a lot of practices all around the world. But what I want to say is that any architect today, who is able to complete a project, especially in the West, where over-regulation rules, where developers are controlling the business of construction, then chapeau! Hats off, really. Great admiration, because it’s not easy at all.

What makes you proudest, thinking back on your two decades of practice?

That I was able to convince my own people, in Gando, to trust me and enter the adventure of coming together to build a school. I am so proud of my people that they allowed me this — they gave me a chance to do research, to work, to build. I learned a lot building with them, and it paved my career, leading me where I am today. So I am most proud of the women and men who believed in me for hours, days, weeks, who kept quarrying stone and working hard to provide the construction site with materials. They did this for someone very young, coming from the community but who went abroad and apparently learned something. They said, “We don’t understand what it is, but we want to support him.” They said, “We will see what comes.”

Interview by Shumi Bose.

Photography by Paul Hutchinson.

Renderings courtesy Kéré Architecture.

Taken from PIN–UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.