INTERVIEW: Niklas Bildstein Zaar and Andrea Faraguna on the Substance of their Architecture Studio sub

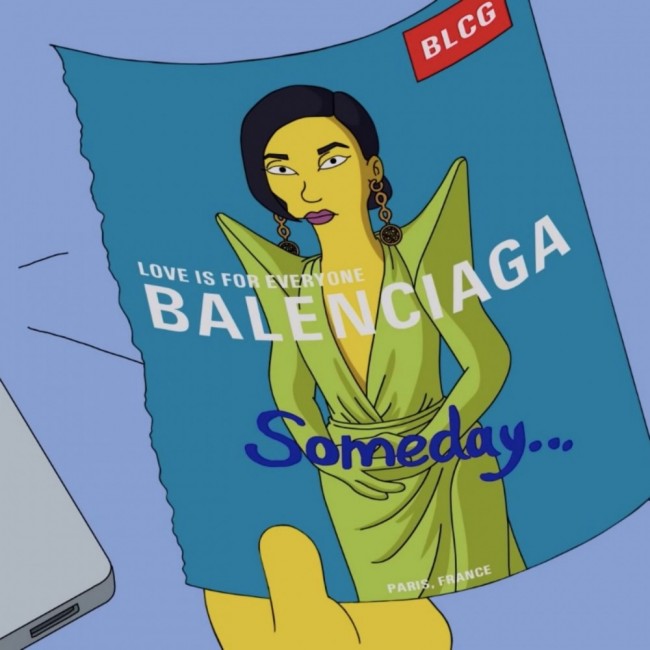

Berlin-based creative director Niklas Bildstein Zaar and architect Andrea Faraguna are are behind the Balenciaga Architecture Program, known for creating the all-encompassing Balenciaga fashion show scénographies that leave both the fashion world and online clout-beasts spiraling. Their architecture studio, which they’ve named sub, was founded in 2017 and operates as both a design office and research institute, one of its self-appointed missions being to understand the metaverse and its manifestation in both the real and the digital world. sub is subverting the meaning of Brutalism, replacing dusty mid-century concrete blocks with a design methodology that brutally forces the audience to face their various complicities. This deeply psychological approach is felt in their collaborations with Balenciaga, the artist Anne Imhof on sets for her performances, as well as with the designer Shayne Oliver on the resurrected Hood By Air’s Anonymous Club — The Glass Ceiling, presented at Luma Westbau in Zürich in September. Despite these high-profile projects, Bildstein Zaar and Faraguna prefer to remain in the shadows and let their work speak for itself. Jordan Richman sought them out in the digital darkness to discuss the substance of sub.

-

Exhibition design for Anne Imhof’s Sex at Tate, London. Photography by Nadine Fraczkowski. Courtesy of the artist.

-

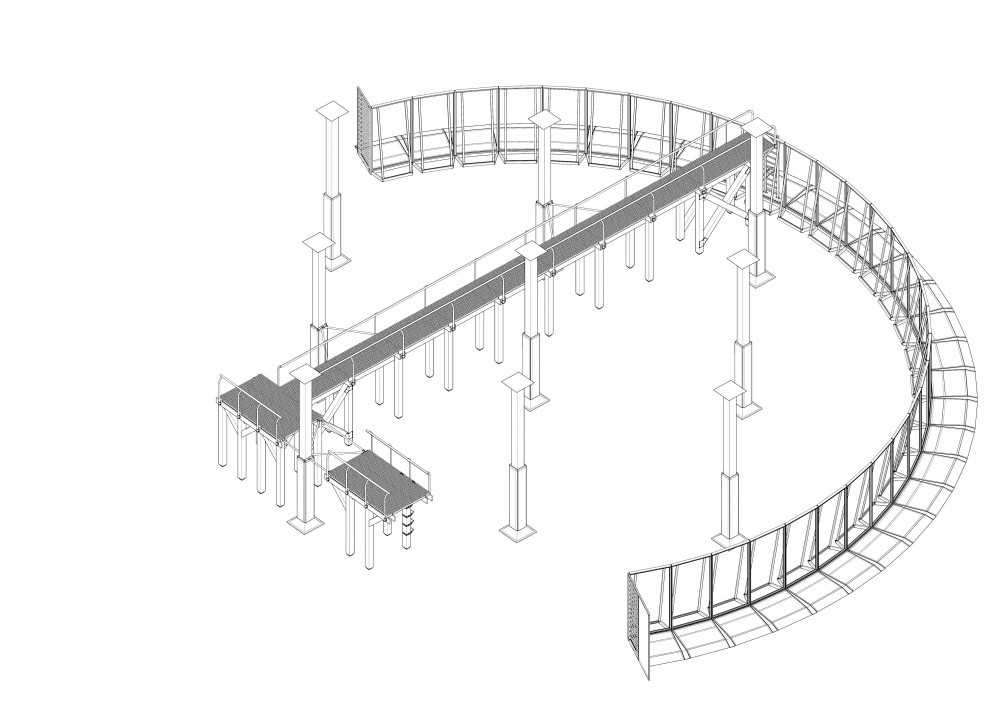

Exhibition design for Anne Imhof’s Sex at Tate, London, Drawing by sub.

Jordan Richman: Why did you name the studio sub?

Niklas Bildstein-Zaar: We liked the idea of the multiple kind of interpretations possible of “sub”: substrate or suburban, substance or sub. There’s an ambiguity to what it refers to. It’s semi-architectural, semi-sociological, semi-anthropological, and I like that kind of open-endedness.

And what does sub do?

Andrea Faraguna: We work collaboratively. The intention is to bring together a mix of individuals from all over the place, with different backgrounds and obsessions. There are team members coming from architecture and engineering, but others from gaming or some kind of worlding. The studio is a community of all these different individuals.

NBZ: The ultimate design exercise is the design of the studio itself. How can you, on a local level, try to create a micro-community that you would like to see deployed on a much larger scale? Things get really existential very quickly. We always wanted to be in between a research institute and a design studio. We have a virtual-world department and a real-world department, so sub is looking at the digital and the physical and seeing how you can ultimately merge them in the most intriguing way.

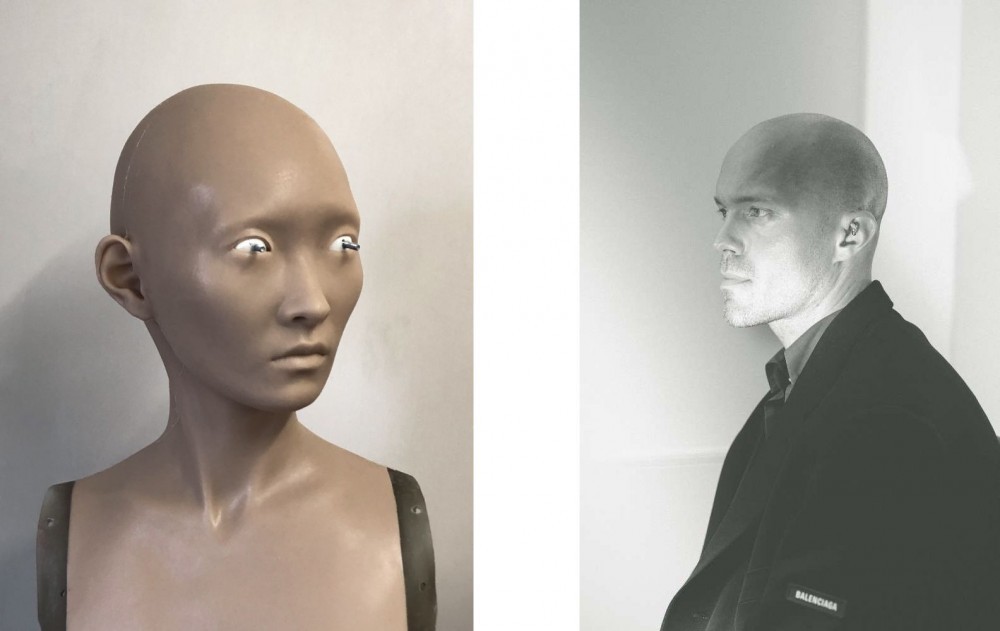

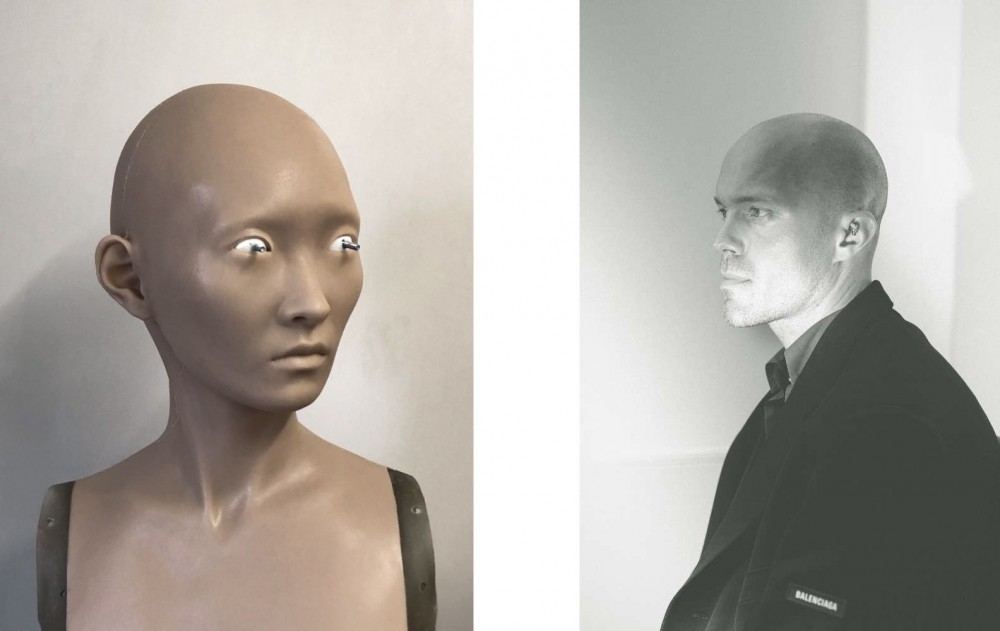

Left: Process documentation of hyperrealistic mannequin designed by sub with special effects by Waldo Mason. Photography by sub. Courtesy of Balenciaga. Right: Niklas Bildstein Zaar of sub. Photographed for PIN–UP by Nadine Fraczkowski.

What is the virtual-world department focusing on?

NBZ: Right now, we’re trying to understand the idea of the metaverse and how that’s supposed to manifest itself — the wave of augmented reality and how it’s integrated into built projects. Because when you talk about the built world, you also need to have an idea of how the virtual world works. There’s an evolution in the metaverse mindset taking place in tech, but it’s happening primarily outside of architecture. It’s interesting to think about environments designed to facilitate what a more digital world will hold. I might regret saying this, but urbanism and platform design, for good or worse, are really not that different.

Can you talk about your collaboration?

AF: We started the studio together about four years ago. We are quite opposite as people — how we think and how we operate can be vastly different, but we’ve found a good symbiosis and counterbalance. We see things differently, but working together we get excited at the same time. I oversee the architectural component, while Nik comes in to give more of a sense of context. We really try to make sure that most of the projects have a philosophical anchor point — or sociological or anthropological. These are the kind of territories of thought that we apply to the practice at large.

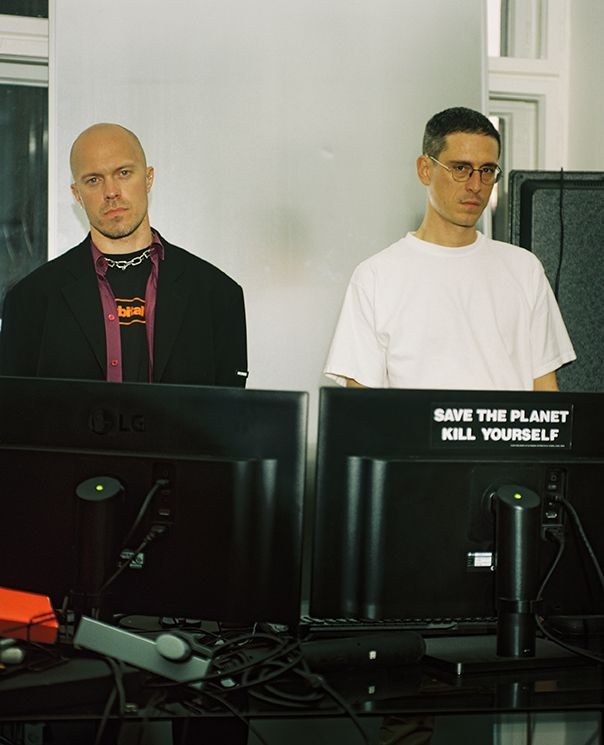

Andrea Faraguna (left) and Niklas Bildstein Zaar (right) of sub at their Berlin studio. Photographed for PIN–UP by Nadine Fraczkowski.

I have a John Giorno piece in my home, and the text is “Space Forgets You.” I thought about that while preparing for our conversation because some of sub’s most interesting physical work, with Anne Imhof on performances, or the Balenciaga shows with their creative director Demna Gvasalia, are fleeting experiences. What is it like to work in such an ephemeral way?

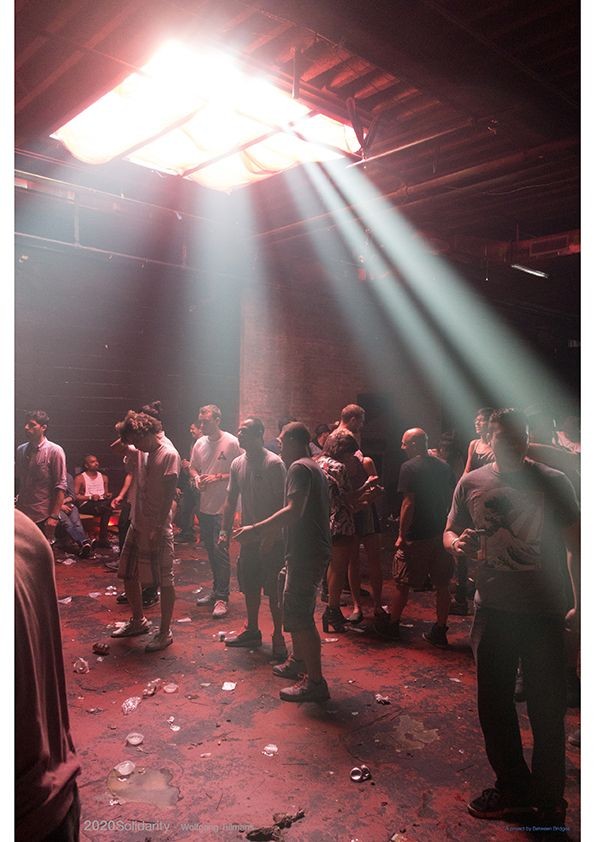

AF: We can’t speak for Anne or Demna, but what is interesting for me is the notion of what is performative within an environment and how that can be enhanced. How do you allow an environment to be open-ended and also a trigger for preconceived behaviors? We’re working on a big Anne Imhof Carte Blanche exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, which will open in February 2021. We’ve worked closely with her to create the architecture of this large-format show. In our work, we try to take advantage of the ephemeral aspect, the constrictions of the space, the brevity of the duration. Usually we intervene in a built structure, trying to rethink the existing condition in order to reveal the spatial tensions of the surrounding environment.

NBZ: For me it’s not really about the performances themselves, but more about the performativity of the audience. Once you recognize that they also function as actors, you can create conditions where you really allow them to face themselves. To observe something and being in relation to something are two very different vantage points.

Left: Balenciaga Autumn Winter 2020 runway show scenography. Photography by sub. Right: Balenciaga flagship store on Milan’s Via Montenapoleone. Photography by Annik Wetter. Both images courtesy of Balenciaga.

How does that translate into watching the Balenciaga shows on YouTube? Are the experiences you create in the physical world also made for a virtual experience?

NBZ: A lot of today’s world is experienced secondhand. It’s been a conversation in the art world for a long time: artists who are making sculptures for the installation photo on the gallery website, where the work really lives on through that static image. There’s an awareness that most audiences will experience the work in this way. Now, however, a multiplicity of other formats is emerging, expanding the viewing potential and transmittal through a variety of devices. If you talk about physical design gestures that have global reach, more often than not they’re experienced digitally. And therefore, of course, they need to become more spatial. For the Balenciaga shows, we certainly know that most people will experience them digitally. It’s what determines how we set the cameras, how we edit the footage, and so on. But the interesting thing, of course, is how to break that paradigm. There’s going to be an enormous revolution within five years in terms of how we perceive space, and that is really going to happen through what is called the metaverse — this idea of IRL experience and augmented reality and all of that sort of merging into one. It’s just a question of time, and I think this is an area that is quite interesting to position yourself in as an architecture studio, being really fluid in understanding what is virtual space and real space and playing with and extending your senses. If you do that, a new type of culture and a new type of social behavior become apparent. Speculating on what that will be is what interests us. There’s a saying, “Man is the measure of all things.” It is a problematic statement, but it does propose a thought: does behavior shape space or does space shape behavior?

Left: Andrea Faraguna photographed by Nadine Fraczkowski for PIN–UP. Right: Still life study by sub.

You’ve talked about plot making. What is your interest in it, and does it apply to your design methodology?

NBZ: In speculative design, you’re building these kind of traps, where you guide people’s perception. We all sit on a sort of communal set of references, which I think is quite interesting to work with. Most of these referential narrative arcs that we’re familiar with — whether from cinema, literature, or anything like that — are reoccurring, and they’ve been sort of perpetually re-representing themselves in so many different contexts. Playing with those individually- and collectively-known signifiers is an interesting place to be because there’s a potential dialogue taking place with the audience, and with myself as the maker of the space. Then, you have to plot. Basically you plan the design experience from before the person has even entered the space, and also even after they’ve left it. You’re trying to understand the context of the space, and what is in the surrounding area and within these kinds of transitory thresholds that you can modify to create a much longer experience. With sub, we strive to create a transformative experience. Most transformative experiences are interpersonal and they appear in life without any kind of planning — it can be something joyous, something traumatic, something really passionate, or whatever it might be. You can’t really control those kinds of life experiences. But within the orchestration of space, you can operate with signifiers and semiotic objects that you deconstruct, reconfigure, and retranscribe. There’s the opportunity to have people walk away from the experience with something lasting, because it’s personal.

AF: I would explain the idea of trapping as a way of framing a narration, suggesting perspective views which are ultimately not unitary. What we do is to manipulate a space, guiding an observer through it by organizing perceptive boundaries, alluding to familiar associations and similarities, offering tools for contemplation and reasoning, to which most of the time we don’t give enough space or importance. I’m fascinated by the idea of simultaneity: a condition in which aesthetical and logical connections and socio-political references — which contradict each other — are cohabiting. I would describe this design approach not as a commentary on the contemporary context but more as a process of digesting it. We aspire to the making of a space that is transformative and transitional, of the crossing and the metamorphic, that keeps together aversion and attraction, euphoria and lament. In the times we live in, these things are happening at the same time.

-

Balenciaga Spring Summer 2020 runway show scenography. Photography by Boris Camaca. Courtesy of Balenciaga.

-

Left: Process documentation of hyperrealistic mannequin designed by sub with special effects by Waldo Mason. Photography by sub. Courtesy of Balenciaga. Right: Niklas Bildstein Zaar of sub. Photographed for PIN–UP by Nadine Fraczkowski.

Niklas, you grew up in Sweden. It seems to me that many Swedish artists and creators are very much into different subcultures. Would you say that about yourself as well?

NBZ: I view my upbringing as a little bit bleak, a little common. But there are also weird things that happen that far north. I’m not sure if you know about Nordic larping? It’s live-action role play, from the time before digital avatars. Nordic larping is really quite advanced because the pretext for the simulated scenario can be really extreme. I recently spoke to the Finnish artist Jenna Sutela about this, and she told me about an incident where people pretended to be terminally ill, and they were just acting that out, which really takes larping to another level. It’s more than the kind of medieval fantasy storyline we usually associate with larping. There is something very Nordic about this, because in our seemingly benign environment people have to apply a heightened layer of narrative. Maybe it’s a consequence of being largely atheist. You create these stories and narratives just to make things a little bit more intriguing. And it really resonates with me. In our very cold, introverted, pragmatist Swedish climate, this is our way of constructing something greater than what we are.

Left: Process documentation of hyperrealistic mannequin designed by sub with special effects by Waldo Mason. Photography by sub. Courtesy of Balenciaga. Right: Niklas Bildstein Zaar of sub. Photographed for PIN–UP by Nadine Fraczkowski.

You also have a keen interest in archetypes. Where does this come from?

NBZ: My father was a soldier, which is a trade with a uniform, and likewise my mother was an air stewardess. I think this idea of going to work and putting on a uniform and becoming that kind of servant is something that has informed my thinking a lot. I have an enormous collection of military uniforms. I also own a surprisingly large collection of air-stewardess uniforms, which is partly inherited from my mother, but also partly collected on my own. (Laughs.) So the idea of a uniform and becoming other through the way you dress and choose to present yourself using archetypes has always been something really defining for me. It naturally made a lot of sense working with identity archetypes as a design methodology for Balenciaga, because it’s a shared mindset with Demna.

When I first approached you about doing an interview, you weren’t sure whether you wanted to come “out of the shadows,” as you put it. Why is that?

NBZ: When you work as collaboratively as we do, the shadows are a good place to be. In this highly-saturated media world, everybody is always craving for some kind of spotlight. But at the end of the day, it’s the work that matters. I’m very much into the CCRU (Cybernetic Culture Research Unit), which was a collective in the UK during the 1990s that worked with a lot of speculative computer science. They had some complicated characters among them, but as a whole they kind of promoted the idea that the CCRU did not exist, had never existed, and will never exist. I always liked the notion that the most powerful and awe-inspiring things are the ones you know as little as possible about. It’s a kind of black-box mentality: what is inside the box is either your dreams or your nightmares.

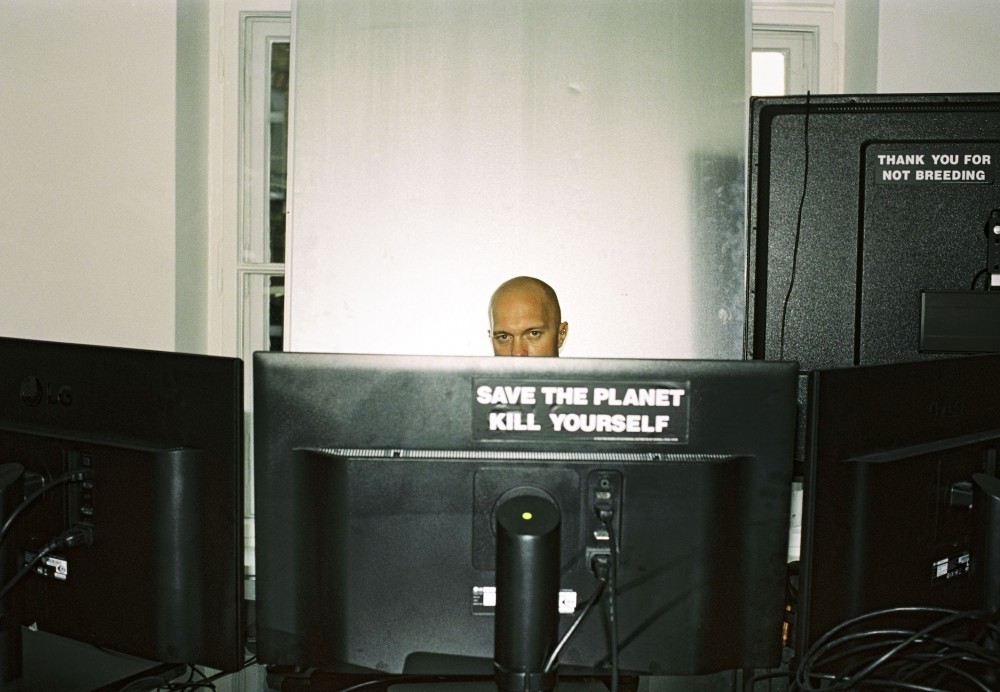

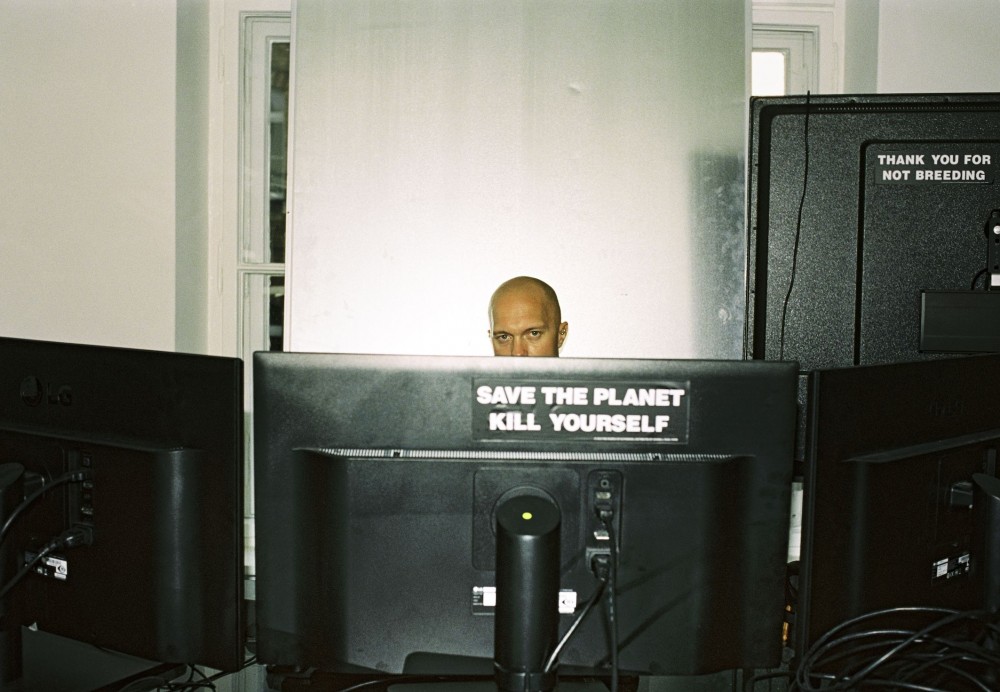

Niklas Bildstein Zaar of sub in their Berlin studio. Photographed for PIN–UP by Nadine Fraczkowski.

I recently downloaded the astrology app Co-Star. On my chart, under Mars and Gemini, it said: “You put a lot of energy into darkness, taboos, rebirths, sex, and transformation.” I thought this also explains my attraction to your work. What’s your sign?

NBZ: I am a Capricorn, Leo rising, and a Pisces moon, I think. That would make me an obsessive drama queen who’s really insecure. (Laughs.) I downloaded CoStar too, and at first I was really into all the daily notifications. And after a while I thought, “This is not what I need right now.” But there is obviously something very interesting to the notion of the “profound” today. Astrology, arguably, is some type of contemporary theology. In this post-truth kind of world, if so many people subscribe to something, it’s true to some degree. I think we’re in a ripe position to really examine what our value system is today.

-

Niklas Bildstein Zaar of sub in their Berlin studio. Photographed for PIN–UP by Nadine Fraczkowski.

-

Balenciaga flagship store on New York’s Madison Avenue. Photography by sub. Courtesy of Balenciaga.

-

Tobias Spichtig, We should be lovers again. Photography courtesy of the artist

And how would you describe your value system?

NBZ: I think we’re ridding ourselves of previously accepted forms of an idealist mindset. Some people talk a lot about this war against sensemaking. In this world we live in right now, you can misguide someone without telling a lie, and I think that’s a very interesting and critical proposition. I think that in the system we live in, that type of behavior is rewarded — it is so much more profitable to be deceptive or act as a defector. That said, I think deep down inside I’m a little bit sinister and I’m trying to overcome that. There was a long period of my life when I had this obsession with calling out people’s complicity and hypocrisy, and I felt that was a kind of design intention and a calling. I used to have this vision sometimes, when I’d walk down the street and see a man, a woman, a child, a postman, or whatever, and I’d think they’re all kind of criminals. We’re all part of this big crime. (Laughs.) I think that’s a little bit of a post-adolescent mindset, rooted in frustration. I’m being a little bit more hopeful now, and I also realize that what you create mirrors the future to come. I think it’s really important to harness that.

Interview and idea by Jordan Richman.

All portraits of sub by Nadine Fraczkowski.

Jordan Richman is an art director and writer based between Los Angeles, New York, and Berlin who focuses on collaborations with contemporary artists in fashion, media, and tech. He creative directed PIN–UP's cover story “Bonaventure Adventure,” photographed by Torso and written by Fiona Alison Duncan (see PIN–UP 28).