HIGH-VISIBILITY: The Shifting Politics Of Safety From Protest Culture To Luxury Design

British police in reflective-striped neon jackets annihilating Brexit protesters. Fluorescent-clothed emergency workers responding to Coronavirus. An army of yellow vests sabotaging the French establishment. A safety yellow Arc’teryx anorak layered over bridal tulle in Off White’s Fall Winter 2020 runway show. In the past few months if you’ve had access to the media landscape in any possible way these images are likely stuck in your mind, hardly forgettable as the textiles in them have been devised for maximum retinal stimulation. Recently, there’s been a boost of high-visibility garments, both in fashion and news images, shifting the subtext of how we interpret signifiers of both safety and luxury. By mimesis, high-visibility dissimulates the tropes of protest, the working class, surveillance, authority, and emergency — and by appropriation, it responds to growing discomfort with the capitalist framework, which its critique is also sometimes subsumed by.

Off-White Fall Winter 2020 runway show, Paris Fashion Week February 2020. Photography Gio Staiano / Now Fashion

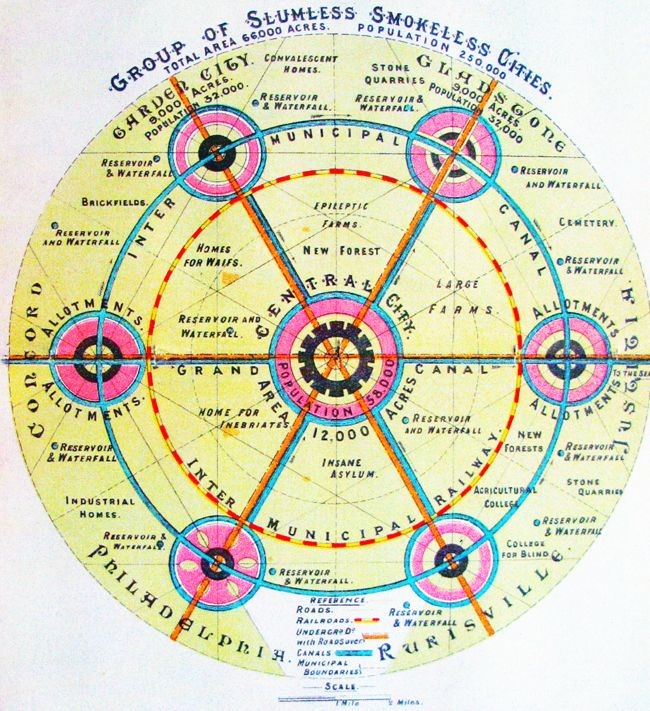

While workwear is a product of the Industrial Revolution, high-visibility workwear is indeed a more recent invention, dating back to the 1930s. At the time, workers unions were gaining recognition and political influence, especially in the US, demanding expanded workplace health and safety measures while labor regulations were beginning to be applied more consistently. In 1930 Berkeley, California, Bob Switzer suffered a coma, following a workplace accident unloading crates at a railroad yard. Following doctor’s orders to stay in a dark room while he recovered, Switzer started experimenting with chemicals that had fluorescent effects, leading to eventually, together with his brother Joe, developing a paint they called Day-Glo. Once applied, Day-Glo made materials shine brightly as if it were daylight even in the dark. The brothers, who were also amateur magicians, first used the paint to achieve optical illusions for their stage acts, but the US military soon took an interest. It was WWII and the army saw the potential for this new technology to help identify troops to aircrafts overhead thereby preventing friendly-fire casualties. They prompted the Switzer brothers to start experimenting with applying the fluorescent pigments to fabrics. By the 1960s, uniforms embedded with fluorescent paneling, and the Day-Glo Fire Orange™ became the standard of safety in aviation.

Hi-vis became more and more ubiquitous, growing into a globally-acknowledged signifier of risk and safety, used not only in the military but also by construction workers, crossing guards, police officers, toll gate personnel, and frontline workers. It’s a short jump from safety to emergency. In a natural disaster, pandemic, civil unrest, or armed conflict — situations where a government can declare a state of emergency and curtail civilian rights — there’s increased demand for hi-vis fluorescent and reflective materials, communicating emergent hazards and alerting people to changes in protocol. Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben situates the state of emergency at an “ambiguous and uncertain fringe at the intersection of the legal and the political,” constituting a “point of disequilibrium between public law and political fact.” Under those circumstances, democracy is potentially under threat of hijacking.

Police arrest anti-Brexit demonstrators during a sit-down protest in London, August 2019. Photography AP Photo / Alastair Grant

After the 9-11 terrorist attacks, then President George W. Bush declared a state of emergency, which he used to rationalize programs of wiretapping and torture as well as military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. In this post-Department of Homeland Security era, military hi-vis gained greater notoriety in the public imagination. Around the mid-2000s, the glow belt became especially iconic, with images from Iraq and Afghanistan showing US troops wearing these reflective belts everywhere, during physical training, walking at night, operating all terrain vehicles, even a pass of sorts to get into the chow hall. These belts shaped the visual narrative of the War on Terrorism, to the point that their renown crossed over into civilian fashion. In 2018, Urban Outfitters started selling their own $30 “Rothco Reflective Physical Training Belt.” The reflective belt had been established as a true icon of the state of emergency.

As the concept of democracy mutates within the post-factual realm, a univocal definition of emergency is no longer applicable. The 2016 US presidential election, populist movements gaining government majority in Italy, the recent right-wing coup of the Hungarian Parliament, and the gilets jaunes in France exemplify how the rise of social media has paved the way for autonomous movements to gain the status of recognized political forces, engineering a crowd-sourced legitimation process for radical ideas. Through audience fragmentation and behaviourally-targeted content, “the people” grew into an identifiable political entity with an anti-elite agenda. As protests around the world are on the rise, one thing is certain: today the state of emergency can be a bottom-up action, a declaration against the establishment.

Gilets jaunes protest in central Paris near the Arc de Triomphe. Photography via The Economist

In October 2018, nearly every newspaper around the world would publish an image featuring hi-vis yellow vests. The movement of the gilets jaunes in France is a top-of-the-iceberg manifestation of a new state of emergency, one that is crowd-deliberated and perpetrated through public violence. The gilets jaunes have no established leaders, no clear aims, and few unifying characteristics, although the movement’s adherents all seem to find a common ground on their dress code: the fluorescent yellow hazard vest that has become synonymous with the French working class’s outcry over fuel taxes. “There hasn’t been such a compelling sartorial symbol of revolt since the Sans-culottes seized on their trousers as the point of visual difference with the aristocracy during the French Revolution,” writes New York Times fashion critic Vanessa Friedman. The gilets jaunes movement understands that in our image-centric culture, to be heard you have to be seen.

Prior to the gilets jaunes taking to the streets, hi-vis gear had been showing up in music videos and streetwear collections — from Yung Lean’s video for “Kyoto” in 2013 to Heron Preston’s collaboration with the New York Department of Sanitation in 2016. The popularity of neon orange, neon yellow, and 3M reflective materials seemed an offshoot of the construction workwear trend which itself had been identified as a variation on the normcore phenomenon from a few years prior — yet another cycle of self-aware appropriation, this one evoking hazard-assessment and utilitarian safety.

Heron Preston x Department of Sanitation New York collection (2016), Superintendent Bag.

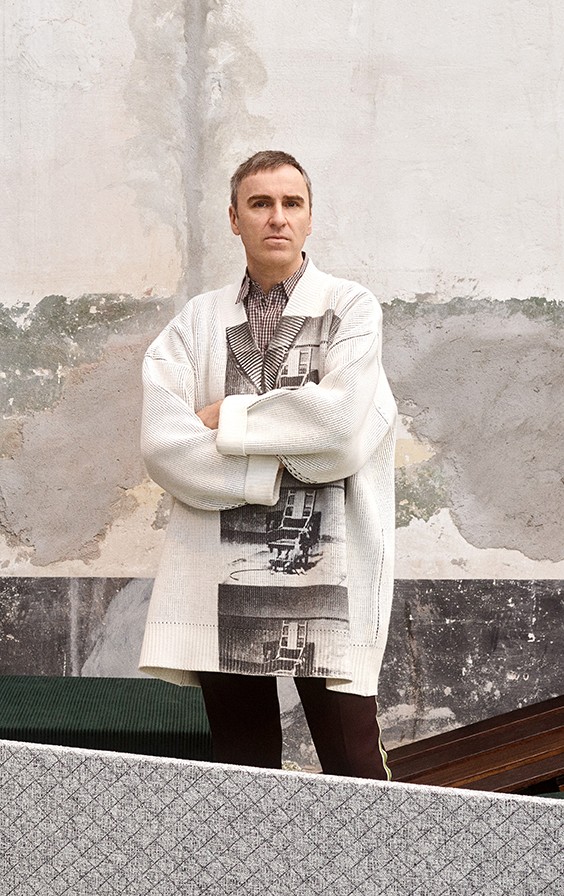

Luxury fashion caught up on the safety gear trend pretty quickly, and the Fall 2018 runway shows acted as self-fulfilling prophecies for the gilets jaunes protests to come a few months later. Calvin Klein’s (205W39NYC) ready-to-wear collection delivered hi-vis stripes, plastic gloves, fireman-inspired rubber boots, and metallic survival blankets styled to accessorize similarly silver dresses. If Raf Simons had been reading Agamben, he wasn’t the only one. That same year, a highlighter-orange coat made an appearance at Burberry’s runway show, and Junya Watanabe’s collection took its inspiration from the uniforms of firefighters, police officers, mail carriers, and sanitation workers — almost every piece with a reflective band.

Calvin Klein 205W39NYC Fall Winter 2018 runway show, New York Fashion Week February 2018. Photography Angela Weiss / AFP via Getty Images

After it was embraced by luxury brands and the fashion establishment, hi-vis infiltrated mainstream consumerism with fast-fashion brands releasing an overabundance of neon pieces, and the media marketing the eye-catching trend as self-expression and a “buzzing” antidote to a lack of confidence. The Kardashian-Wests were early-adopters — Kim even matched neon outfits with her neon yellow Mercedes SUV — their trendsetting eventually spawning an army of Instagram influencers in highlighter-hued sweatshirts.

Kim Kardashian matching her outfit to her neon Mercedes Benz SUV a gift from Kanye, August 2018. © MEGA

Just as the gilets jaunes suggest a decentralization of emergency, the circulation of neon fashions in some ways challenges the expected top-down path from luxury to fast fashion. Balenciaga — a brand well-versed in post-ironic appropriation at the weird intersection of Reddit theory and Austro-Hungarian aristocracy costume — first introduced fluorescent hues in their Spring Summer 2017 ready-to-wear collection: instant classics like the spandex stocking-boots appeared in neon yellow, hi-orange, and shocking pink. But as hi-vis was embraced by Instagram influencers and fast-fashion brands, Balenciaga didn’t shy away. Instead, through best-selling items like the World Food top or the Triple-S sneaker, the house carried on the hi-vis trend, acknowledging the situational power of luxury when it comes to representing authority in mass-culture. The luxurification of emergency in Balenciaga is of no less importance than the politicization of emergency discussed above — in this process, citizens equal customers and populism extends its definition to top-tier price tags.

Balenciaga, Triple S Distressed Sneakers in yellow.

Psycho-effective hues are absorbed and represented by visual culture as signifiers for a hyper-accelerated political context, and the new state of emergency becomes a direct response to the new state of anxiety. According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, safety needs are considered foundational, second only to physiological needs like air, water, food, shelter etc. In the current scenario of existential turbulence — when “stay safe” has become the default valediction and safety has been increasingly revealed as a luxury — we can’t help but strategize coping mechanisms to reconnect to the self, address the brutality of the neoliberal day-to-day, and strive for visibility in systems that overlook our humanity. But should this process be exploited for a fashion brand’s bottomline, or micro-influencer’s social clout? A millennial, fashion-woke version of the gilets jaunes is the last thing we need.

Text by Federico Sargentone.

All images courtesy of the author.