BOOK CLUB: Artist-Researcher Susan Schuppli On Her New Book Material Witness

Artist-researcher Susan Schuppli’s new book, Material Witness: Media, Forensics, Evidence, deals, almost preemptively, with the consequential capacities of matter, and its potential to bear more-than-human witness. The book introduces “material witness” as an operative concept for examining how matter records evidence of violence, alongside the myriad procedures that bring its testimonies into legal forums. Moving between case studies that include Vladimir Shevchenko’s 1986 film, Chernobyl: Chronicle of Difficult Weeks, on celluloid underwritten by radioactive waste, and the overwritten “silence” on Tape 342 of the Nixon White House Tapes, Schuppli’s analyses push us into perceptual chasms, where evidences, however trace, might be retrieved through forensic attentiveness to mediatic specificity.

Material Witness: Media, Forensics, Evidence, by Susan Schuppli (MIT Press, 2020).

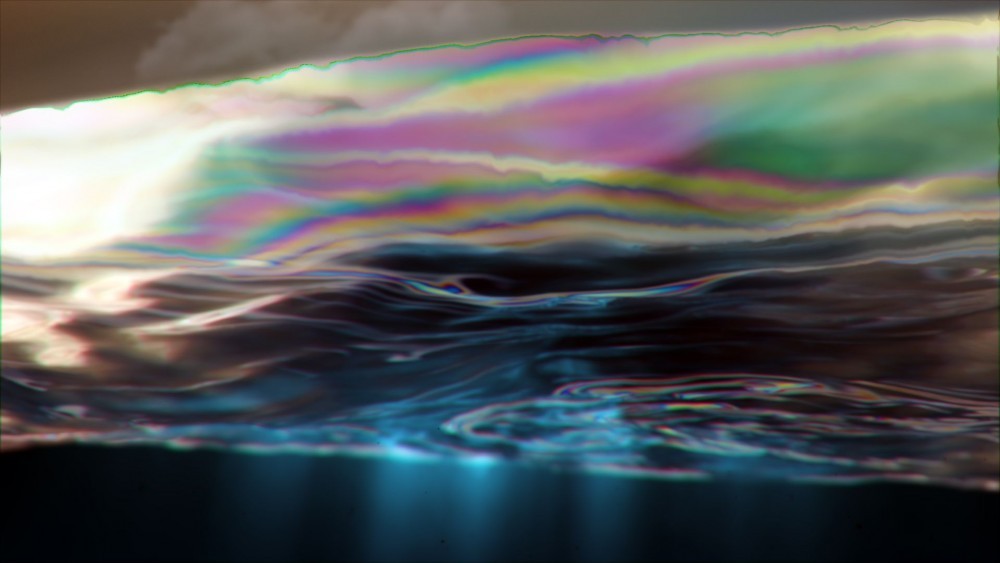

Elsewhere, Schuppli’s investigations have found form in documentary films and photographic installations: her video works Slick Images and Nature Represents Itself (2018), shown in SculptureCenter’s 74 million million million tons exhibition, take the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill (dealt with in Material Witness) to be a new form of self-representing cinema; an eco-aesthetic event of “geo-logical-media.” Schuppli’s thinking offers pathways for how material witnesses can act as agents of accountability within and without juridical contexts, helping implicate perpetrators of climate, war, and other slow-violent crimes of vastly distributed scopes.

Evidence vault of the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP). Photography by Damir Sagolj. Courtesy Reuters.

I studied with Schuppli at Goldsmiths’ Centre for Research Architecture, where she is currently Director & Reader of the Centre for Research Architecture. She is also on the Advisory Board Chair of Forensic Architecture, a Goldsmiths-based research agency led by Eyal Weizman investigating human rights violations and political violence. I corresponded with Susan by email.

Emma McCormick-Goodhart: You cite philosopher Isabelle Stengers’s provocation to tune ourselves to matter — to let it ask questions of us — as a pivotal starting point in your project, Material Witness, which probes the evidential aspect of matter by setting out a framework for a “testimony of things.” How does your inquiry, and its scope, into “sounding” matter complicate New Materialist thinking, wherein materials are held to possess agency?

Susan Schuppli: I suppose my background as a practitioner (artist/research architect) has a crucial role to play. My conceptual insights emerge out of my practical engagements such that I don’t approach situations with a set of guiding questions or even methods at the ready, but rather am interested in a specific condition, which in turn may eventually give rise to key questions or be suggestive of specific approaches to conducting research. It’s not about arguing for the expressive potential of matter akin to the linguistic formulations of speech, but is rather about how practical engagements with the material strata of the world can be generative of new insights and modes of working. Throughout the book, I have tried to account for the myriad ways in which the responsiveness of matter to external forces demands an acute and renewed sense of material specificity — what might be considered attuning ourselves to matter — in order to grasp the full political implications that such ongoing changes or interactions might yield.

-

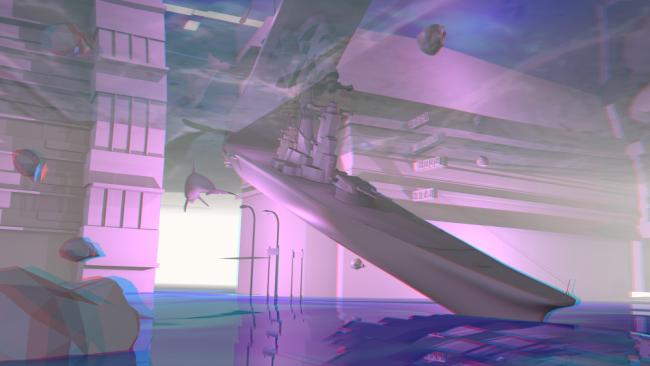

Susan Schuppli, Nature Represents Itself (2018): oil film simulation of surface slick as well as deep subsurface plumes resulting from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Commissioned by SculptureCenter for the exhibition 74 million, million, million tons curated by Ruba Katrib and Lawrence Abu Hamdan. CGI video produced in collaboration with Harry Sanderson, color with sound 6:27 minutes.

-

Susan Schuppli, Nature Represents Itself (2018): oil film simulation of surface slick as well as deep subsurface plumes resulting from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Commissioned by SculptureCenter for the exhibition 74 million, million, million tons curated by Ruba Katrib and Lawrence Abu Hamdan. CGI video produced in collaboration with Harry Sanderson, color with sound 6:27 minutes.

Can you draw out the difference between “evidence of the event” and “the event of evidence,” a distinction central to the book? In which case within Material Witness were these furthest apart?

These two conditions are perhaps the most salient features of the Material Witness. All entities are capable of registering evidence of external events, which can in turn be forensically disclosed or decoded using certain techniques and procedures. In some cases, such as with a crime scene, these traces can prove to be consequential, but in general this insight won’t get us too far, in that only certain events are usually deemed worthy of consideration — and certainly not all traces become forms of evidence. The material witness also needs to ask or inquire into why this happens — why are some situations or subjects considered relevant, and why are others dismissed or ignored?

A case in point is environmental change. There is a long history of observations that have been part of the life-worlds of indigenous people, but the methods for recording these histories and the accounts given in customary practices — such as oral traditions — haven’t been regarded as a significant repository of knowledge by climate change scientists until quite recently. With this example, one could say that the “event of evidence” refers to the partisan practices and protocols governed by epistemic frameworks that determine the specific relevance of certain modes and forms of witnessing. Consequently, the project also reflects upon the specific requirements that must be met to secure “legitimate” acts of witnessing, from legal tribunals to climate change summits, as they adjudicate over whether certain kinds of observational practices and testimonial methods should be enlisted or rejected. In turning my attention to the legal domain, I was able to see these evidentiary logics working themselves out in perhaps their most prominent articulation as a distinct realm of procedural expression subject to agreed-upon conventions that turn on questions of expertise.

As to the second part of your question, perhaps the case of the Chernobyl trial in 1987 offers an example whereby the material evidence of radiological contamination, and the paper trail corroborating the inferior design of the RBMK graphite-moderated light-water reactor, didn’t guide any of the legal determinations that were entirely focused on scapegoating lower-level personnel. I suppose the “event of evidence” with respect to the trial could still be seen as one in which the complete disregard of any material evidence furnished a kind of proof in and of itself as to the politics at play within the legal performance of the trial.

Susan Schuppli, Disaster Film: a public billboard series installed throughout Vancouver for the exhibition Signals from the Sea, curated by Jayne Wilkinson. Courtesy Capture Photography Festival, 2019.

You pay forensic attention to the different affordances of digital and analog material witnesses, whether filmic negative or glacial ice, and their varying modes of preservation and playback — no doubt informed by your own practice as an artist-researcher, who often works with analog film. Why is it especially crucial for your project to think “the digital analogically?”

Throughout the book one encounters computational processes that are continually transformed into analogue objects to ensure their legal probity. Hard drives are preserved to secure digital files, CDs are photocopied to confirm chain of custody. Because the book has a legal spine, it was important to emphasize the degree to which the digital is time and time again subject to analogue processes and logics of objectification.

No doubt, the concept of the material witness is easier to grasp as an analogue form, in that storage mediums, such as film stock, photographic negatives, and magnetic audiotape, are particularly receptive to registering external events because their surfaces allow them to archive trace evidence through direct contact or exposure. Walter Benjamin’s discussion of the auratic capture of external events – made possible by the lengthy exposure times demanded by nascent photographic practices – is provocatively congruent as a kind of precursor to the material witness. For Benjamin, the temporal darkness out of which an image struggled to assert its presence meant that the surface of the photographic plate was saturated with the aggregate history of the subject’s environment – thus establishing its aura. The digital, while not impervious to noise and interference, must by definition recalculate and absorb this intruder data into its coding chains, whereas external interference within analogue domains sits side by side with the “proper” subjects of inscription, since there is no mechanism for reintegrating such extraneous information.

When it comes to sound events, the digital is always experienced as an analogue event. Digital sound files enter the body as analogue waveforms to vibrate and activate our receptor organs. Much has been written of late that explores the material infrastructures and geological, as well as extractivist, origins of computation. Thinking the digital analogically is a recognition of the fact that this is an enfolded condition that doesn’t benefit by asserting an ultimately false analogue/digital divide.

How does sound, in particular, whether emitted low-frequency in drone warfare, or withheld as in the erased 18.5-minutes on Tape 342 of the Nixon White House Tapes, push the perceptual limits of the law?

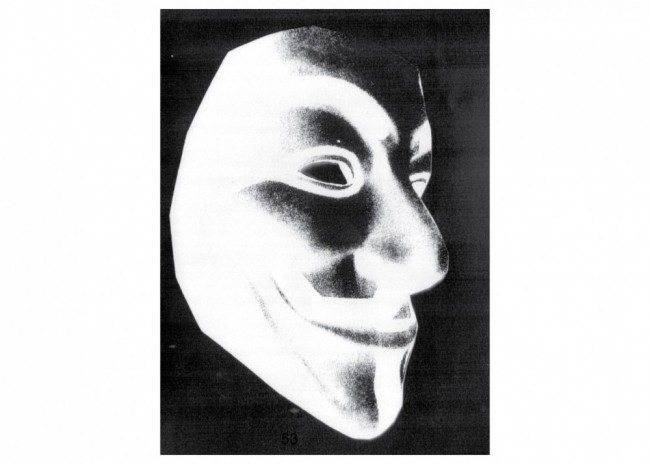

I focus several chapters on sonic artefacts precisely because, as you ask, the legal burdens of proving direct causality, or meeting the pillars of distinction and proportionality as set out by international humanitarian law, are severely challenged by the unique capacities of sound waves to propagate spatially. The armed combat drone operations over the Afghan border with Pakistan during the height of the “war of terror” offer a case in point, as the prevailing argument around the precision of a hellfire-guided missile strike was its most salient feature — but the combined propeller and engine noise produced by near continuous drone surveillance resulted in a background stratum of diffuse harm (150 kHz frequency) that produced extreme anxiety, stress, and social disruption. While these sounds were not lethal, they did signal one’s potential imminent death, and thus one could ask certain legal questions around the role of sound in the punishment of civilian populations. In the chapter focusing on the missing 18-1/2 minutes of recorded sound in Watergate Tape 342, the legal move was in fact not so much a question of sound, but rather one in which an act of negation was transformed into incontrovertible evidence of political malfeasance and criminal wrong-doing — the absence of intelligible speech on the tape, in the form of Nixon’s bungled attempts at erasure, became evidentially damning.

Record Group 21: Records of District Courts of the United States; U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia; Watergate-Related Cases; Miscellaneous Case 47-73 (In Re Subpoena Duces Tecum Issued to Richard M. Nixon for Production of Tapes, Etc.); Government Exhibit Number 60: UHER 5000 Reel-to-Reel Tape Recorder. Courtesy US National Archives and Records Administration.

“Anthropogenic matter is relentlessly aesthetic,” you write, generating “dirty pictures” of damaged ecologies, such as the self-representing Deepwater Horizon oil spill: both new form of cinema and mode of data capture, you argue. How would you propose migrating aesthetics — and a conception of the “geo-media-logical” more broadly — into the Anthropocene debate, and/or into legal studies or juridical contexts? Can aesthetics help advance the cause of environmental accountability?

To be honest, I really don’t know. It’s a question that I continually grapple with — the operative role of aesthetics in producing regimes of accountability, or at the very least, raising political demands. To argue for the aesthetic agency of an environmental system seems no less abstract to me than a legal formulation — of which many examples now abound — whereby natural entities have claimed legal rights. (Forensic Architecture has, arguably, paid considerable attention to the aesthetic as an investigative condition and mode of rhetorical persuasion.) Throughout the book project, I try to move away from a consideration of mediatic entities as representations that point to an external reality in order to explore instead the ways in which materials are an-indexical to themselves. This is the argument that I try and develop with respect to the radiologically contaminated film shot at Chernobyl in 1986, as well as the Deepwater Horizon disaster of 2010. These aesthetic events of chemistry and light refraction (as is the case when hydrocarbon atoms interact with water and sunlight to create what is technically called an oil film or oil slick) exist prior to their externalization in the form of a representation, and are thus all the more ontologically real.

What do you anticipate in the way of futures of (and future frameworks for) “environmental image-making?” Will it require rethinking imaging, sensing, timescales, and who counts as a maker, altogether?

I know a few artists and filmmakers who, like me, are trying to figure out how we might work more directly with environmental processes and materials as part of the image-making process, rather than simply turning our camera towards such events. Snowflakes are fantastic optical systems, but how to work with them as a lens-based technology to develop a project together? How can my practice as an artist not become extractivist in nature, or about the use-value of ecological matter in furthering my artistic methods? I haven’t resolved this fully, but take it on as a guiding ethical principle and goal.

Can we conceive of material witnesses as alternate modes or sites of perception? I’m thinking of your formulation of matter as a “sensate mediator.”

Yes, in fact, why not? I like that characterization a lot, but would still want to stress that considerable labor is required to transform modes of sense perception into actionable events. At the risk of overstating my case, I’d like to think of material witnesses as radicalizing perception in that they are always engaged simultaneously with the politics of what and whose modes of perceptions matter and why.

Susan Schuppli, Atmospheric Feedback Loops (2017): 35mm vertical color film with stereo sound, 18 minutes. Courtesy Sonic Acts, Amsterdam.

What can architectural and spatial practices draw from your notion of “informed material,” or of the material witness as a technology of assembly of stakeholders?

Just to be clear, “informed material” is a term that comes from Isabelle Stengers and Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent in their 1996 book, A History of Chemistry, where they discuss the ways in which new materials are invented to solve specific problems. Geographer Andrew Barry has subsequently also used this concept, and it was through his work that I first encountered it. In my analysis, matter is a question of properties — the capacity of materials to register change resulting in an accrual of information — rather than an issue of property out of which surplus value might be extracted. What I find particularly helpful is that it allows me to avoid the partitioning of media into analogue and digital domains, or even into concrete entities at all, when making my arguments around environmental and elemental media. In borrowing this concept, I explore how the condition of informational enrichment allows us to read history, and ultimately politics, back out of the complex material strata of our world. Architecture is a practice that intervenes in the world — thus its projective nature — always engaged in transforming materials, which are themselves, at every moment, co-constitutive in registering change. I would say that stakeholders gather when the specific relevance, or the significance accorded to information at its various perceptual thresholds and scales of assembly, are brought into question, contestation, or dispute.

Are design propositions needed for reimagining forums?

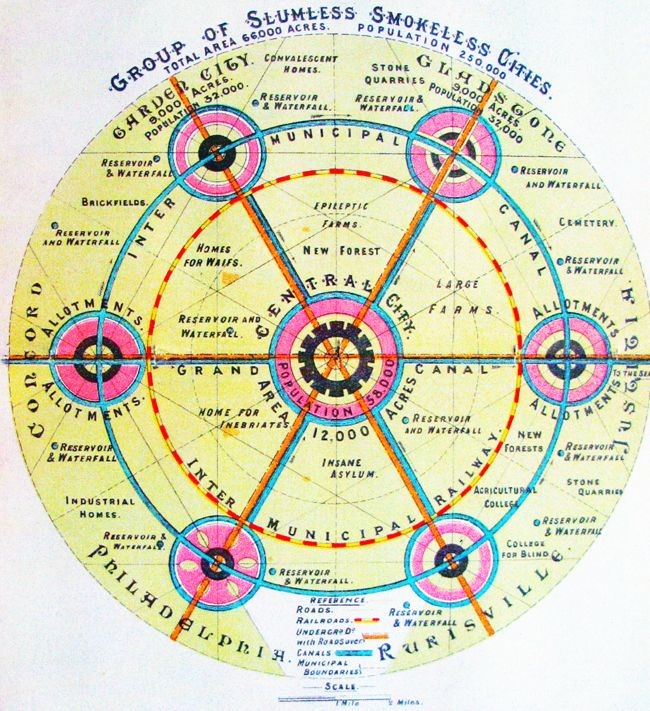

Absolutely, in fact, it’s essential to understand the operative role that design has played in the production of violations: from the re-design of Portuguese sailing ships, known as caravels, with aerodynamic hulls and triangular sails that could manage the coastal currents of West Africa and thus enabled the transatlantic slave trade (something my colleague Ramon Amaro here at Goldsmiths has worked on), to the design of the contemporary courtroom that continues to spatialize power according to clear hierarchical principles. If new forms of justice are to be imagined, and ultimately enacted, then the injustices structured “by design” have to be called into account. Some would argue that the logics that produced the system can’t be utilized in its radicalization or overthrow — but I do feel that another design is possible, and that there are many fantastic examples that we can look to for inspiration.

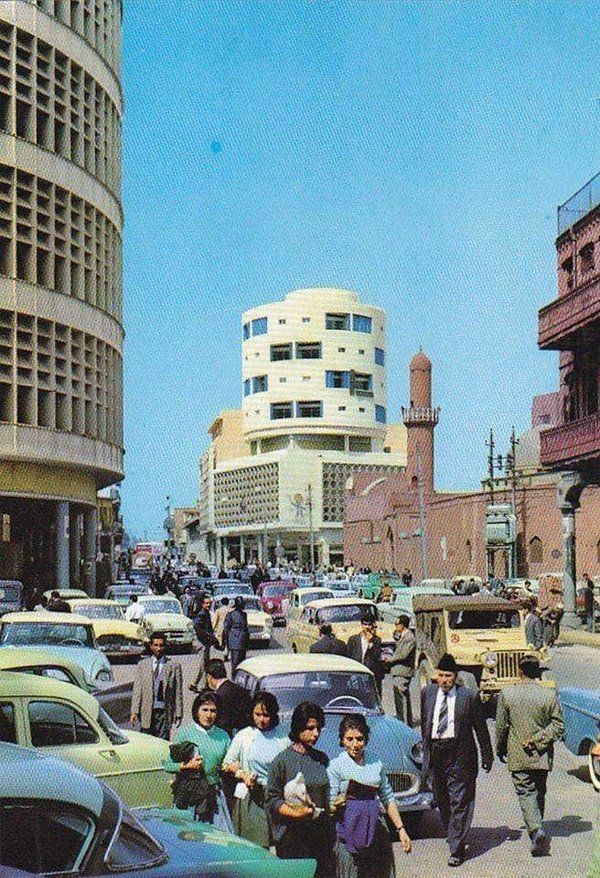

Models of restorative justice, for example, that include peacemaking circles and healing lodges. While such socio-spatial designs have emerged out of the customary practices of indigenous peoples, they are also being used more widely. I appreciate the propositional thinking of architects Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha in projects such as Soak (Mumbai) and Oceans of Rain (Ganges and Ganga), as well as their provocative book, The Invention of Rivers, that undoes the terrestrial-aquatic partition. Naiza Khan, one of our current MA students in Research Architecture at Goldsmiths, has been researching the Orangi Pilot Project in Karachi and the activist work of architect Parveen Rahman (1957–2013), who developed a method of walking the lanes to learn and work with communities living in extreme economic and social deprivation. In his New World Summit projects, artist Jonas Staal has developed new spatial forms — what he calls “alternate parliaments” — for creating political dialogue by hosting groups excluded from democratic processes. Decolonizing Architecture Art Residency, or DAAR, has produced lots of spatial interventions within the context of Israel/Palestine, including thinking through the deeply conflictual challenge of how to live in the “masters house.”

Ukraine and Russia. The central banner demands “A Nuremberg Trial for Chernobyl.” Photography by Igor Kostin. Courtesy Sygma/Corbis.

COVID-19 has led to a surcharge of public awareness of aerosol and molecular microarchitectures, and of the consequences of our own “trace” presences in space and on surfaces. Even utterance can cause infection. What can we extrapolate from the concept of the “material witness” as we attempt to make sense of the virus’s vast, distributed, and networked nature: one that, to borrow from your discussion of nuclear matter, “contravenes material borders?” Is the virus itself, in any way, a material witness?

It’s important that the concept of the material witness has continual and renewed traction, so I think your musing around COVID-19 links up with various sections in the book on the provocation of invisible events that don’t organize themselves around the registers of human perceptibility, nor behave according to the integrity of sovereign borders. These events are often highly dynamic and globally dispersed, thus raising significant challenges to issues of accountability and questions of environmental justice. While I mostly focus on toxic events in the book (radiation, airborne pollutants, and rainbow defoliants used in Vietnam), it does make sense to consider these kinds of pandemic events as well within this category of transversal actors.

Is the virus a material witness that can testify or indict the practices of factory farming, which have been posited as a breeding ground for pandemics? Or does the invasive breach of the virus into the respiratory tracks of humans transform the body into a material witness that can testify to external events? Perhaps. But this is where we need to return to my insistence around the dual nature of the material witness as also disclosing the “event of evidence.” I would say that the virus has already offered up significant evidence as to which forms of expertise are of notable consideration; which subjects are deemed worthy of protection and concern; and which bodies are all too easily expendable. In this sense the virus is both an imperceptible agent of harm, but also an entity that has been laid bare, rendering into unequivocal visibility the inequalities that the aggressive dismantling of the welfare state has wrought.

The book’s practice-based counterpart is your own ongoing body of work as an artist, which often takes form as photographic and video installations, and films. Your vertical film Atmospheric Feedback Loops (2017), for instance, chronicles a semiotics of signal and noise in experimental atmospheric research. How does making work incubate your thinking?

It’s a reciprocal process, of course, but writing is an important place for me to organize my thoughts and to start to develop a narrative structure for my artworks — especially my documentary projects. At the same time, my aesthetic sensibility shapes the texture of my writing and conditions the kinds of stories I wish to tell. I am always looking for those moments when different practices connect or hold something in common; when certain kinds of concerns, and even modes of investigation and understanding, are shared between disparate fields of research.

As someone who is invested in sonic epistemologies as you are, Emma (readers of PIN-UP may not know that Emma was a graduate student in the Centre for Research Architecture, whose work on deaf space and dissertation project, Auscultating Non-Auditory Geographies, was an inspiration to many subsequent MAs), I might add that the whole book was crafted by speaking each sentence out loud to myself. I would never commit a sentence to the page that hadn’t already been spoken verbally as to its acoustic valence and rhythm. If I stumbled over words, or found the narrative flow awkward, I would need to re-write it. Material Witness was an act of speech making in as much as it was a work of writing.

Interview by Emma McCormick-Goodhart.

Images courtesy Susan Schuppli.

Material Witness: Media, Forensics, Evidence, by Susan Schuppli (MIT Press, 2020).