INTERVIEW: Artist Theresa Chromati On Complexity, Intuition, and Public Art

Guyanese-American painter Theresa Chromati’s first institutional solo exhibition Stepping Out To Step In opened in June at the Delaware Contemporary. Accompanied by a mystical soundscape composed by Baltimore-based electronic musician Pangelica, Chromati has designed three colossal 20-foot by 30-foot banners plastered on the exterior of the Delaware Contemporary, the institution’s inaugural exhibition in a new public art initiative titled Platform Gallery. Chromati’s figures, showing the multifaceted-ness of Black women’s experience, dance along the metal cladding of the museum building, a former railcar factory — the figure in her work shapeshifting, transforming, unapologetically and chaotically existing in the landscapes of a world she made up for herself. The banners and soundscape will be on view until November 30, functioning as a preview for a painting exhibition by Chromati that’s set to open inside the museum in September.

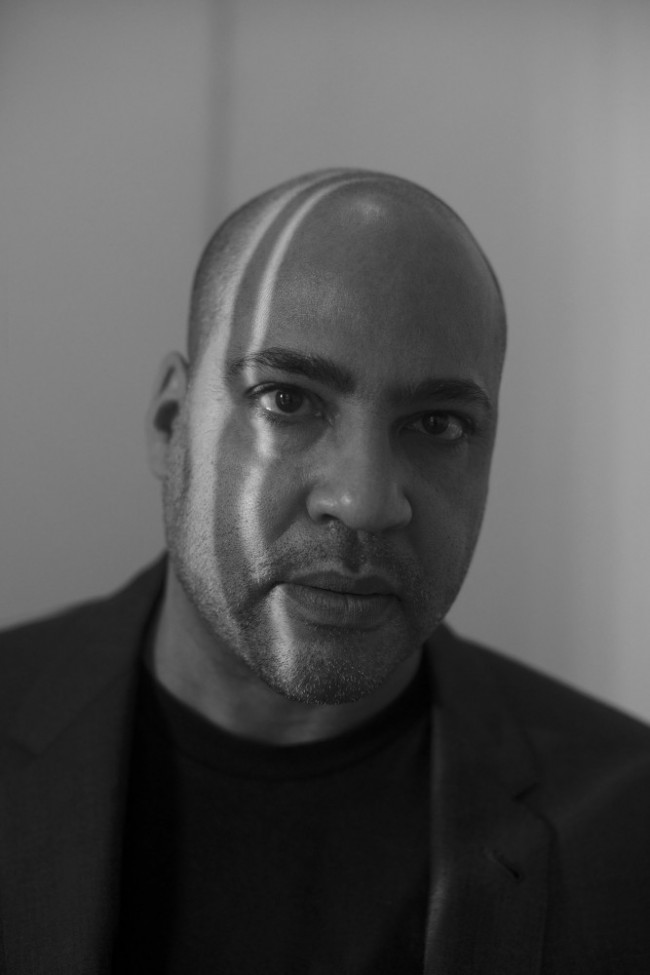

Artist Theresa Chromati photographed in her studio. Portrait by Lyndsy Welgos.

One can’t not think of the mechanization of the female body, and especially Black women's bodies in the United States, when looking at this exhibition on the building it’s placed. Black women’s bodies are socially upheld to be these strong yet monolithic multitasking tools for domestic and emotional labor for white people and Black men. Although Chromati’s paintings don’t confine the Black female body into a white patriarchal lens, I don’t believe she is trying to prove anything to whiteness or maleness. The figures in her work are just existing. And that for me, as a Black queer person, provides a sense of relief. I love that Chromati’s work feels like a politely unbothered snatch of self-reclamation, full of an audacious sense of birthright entitlement. Black artists are always asked to center whiteness or interrogate trauma in their work. Chromati does neither. The figure in Chromati’s work is a fully autonomous being who, through reflection and action, materializes a resistance that is full of healing and self-empowerment. Chromati’s work in the midst of this very metally, once industrial zone, feels like a surreal post-futurist poetic clash with the world we exist in. I spoke with the artist about her approach to this public commission, the evolution of her practice, and representing movement and complexity through figurative forms in architectural environments.

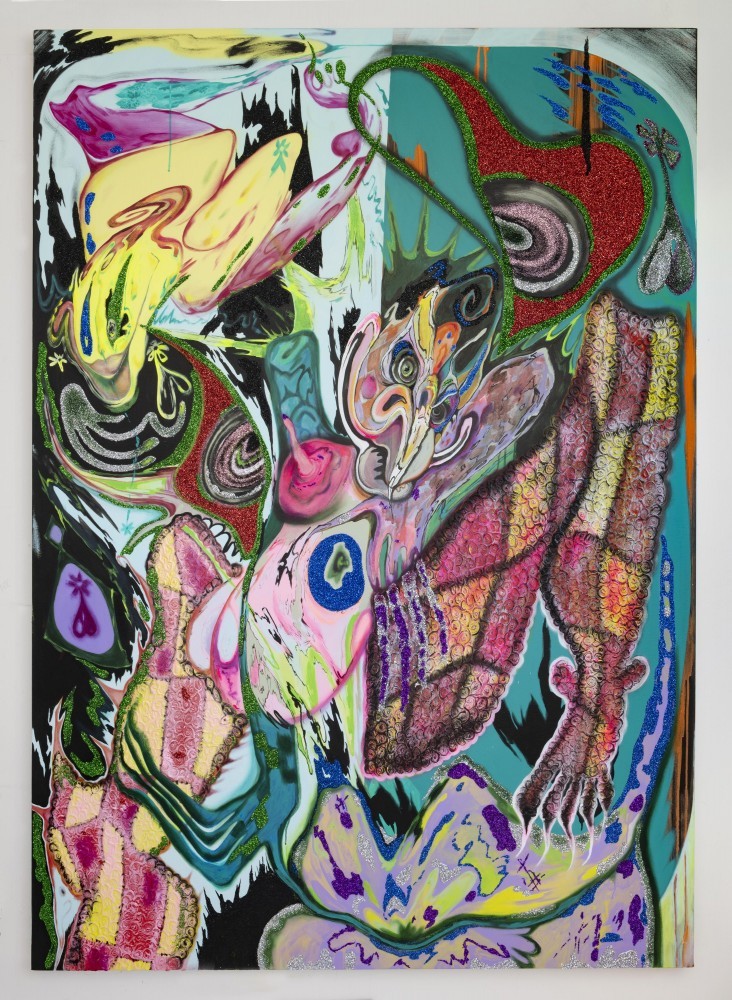

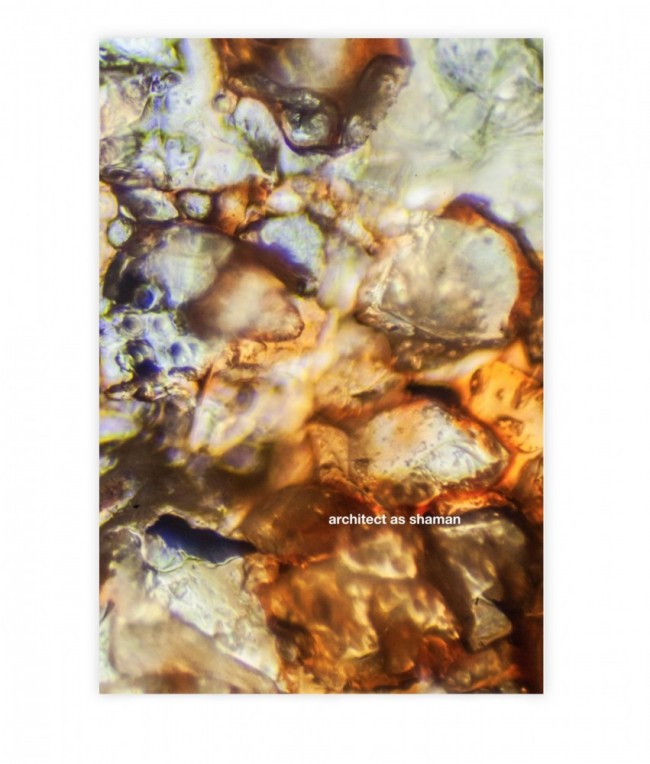

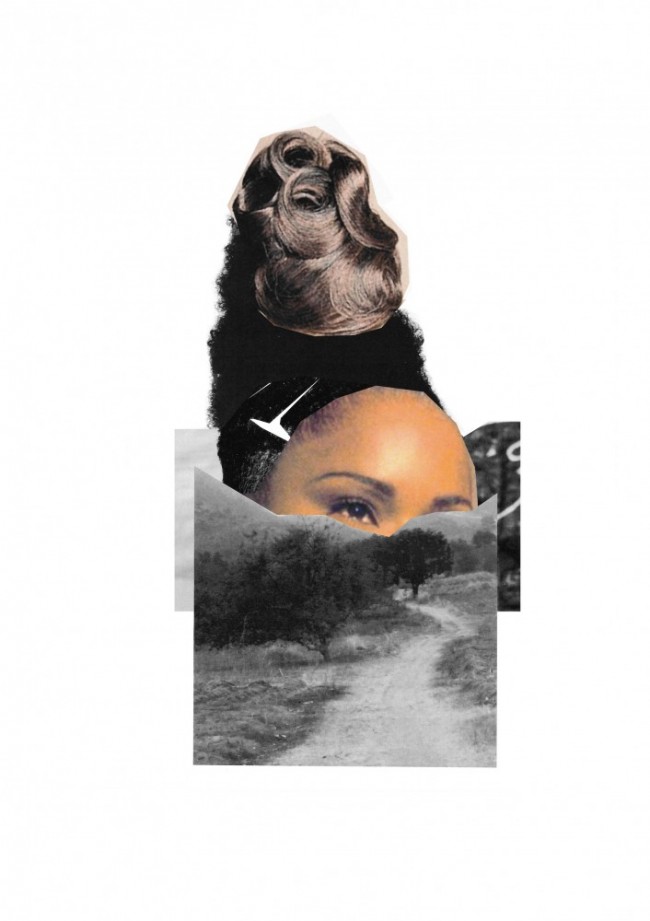

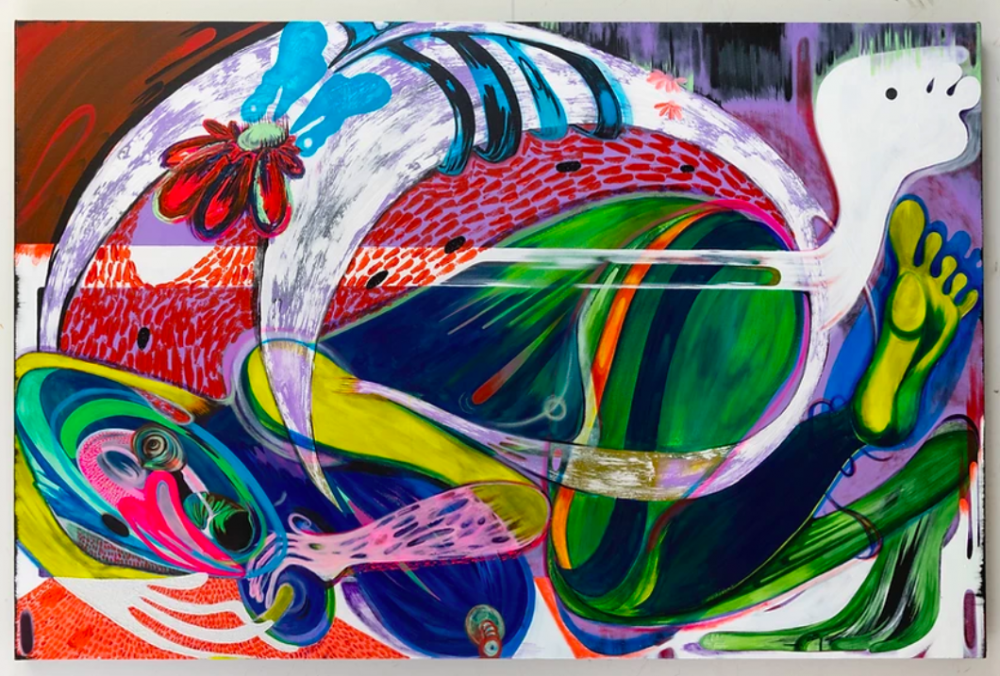

Gathered a Bunch of Scrotum Flowers and Now I Am on My Way (She's Getting There Isn't She) by Theresa Chromati, published edition of the banner currently on the façade of The Delaware Contemporary. Digital print with unique glitter embellishments and silver grommets, 60 x 60" (2020). Available through Kravets Wehby Gallery. Courtesy of the artist.

Tell me about your process, making these pieces for the façade of the building. They're pieces that you designed digitally? At first, I was wondering how the fuck you can make such big ass paintings.

Yeah. It was an interesting process just ‘cause, you know, I started off working digitally with graphic design and then grew my practice into painting. Working with paint has definitely opened up the language to be a lot more loose and even opened up the concepts of the work. It’s blossomed into being more autobiographical, being about this explosive journey that this woman is going on throughout her life. So now, it’s been really interesting working graphically again, going back to the computer and just, like, sitting down. Working that way, everything about your body language is just completely different. It was definitely challenging at first thinking, how can I create this digital triptych in a way that feels part of the same conversation as my current practice?

Compared to my older digital work, I’m playing more with opacity and gradients, looking for new ways to apply texture in a digital work that’s reminiscent of texture that’s actually in the paintings. The main reason why, in my paintings, I’m using glitter and building it up in a sculptural way is this context of women being very multilayered and very textured. Applying these rough and coarse swirly textures. I was like, how can I get this energy for the digital work?

Stepping Out to Step In, an exhibition by Theresa Chromati at The Delaware Contemporary. Courtesy of The Delaware Contemporary.

Thinking back to this era you’re talking about when you were working digitally, making flyers for nightlife and music events — obviously I was a part of that history (laughs). (Chromati designed the flyers for the Kahlon series Ali organized 2013 to 2018). I remember around that time, you also did these arts electrical boxes in Baltimore. So, is this part of the show at Delaware Contemporary your second public art piece?

This is the third, but definitely the first that’s on such a large scale. The second one I did when Elliott Jerome Brown Jr. was curating at MoCADA. It was called Tea Time and was kinda like, the birth child to this ‘cause it was on a smaller scale. It was like a six-panel piece that was outside and that had an accompanying soundscape. It was my first experiment putting these bold images outdoors and partnering them with sound. Some people were kinda shocked. The soundscapes can be very calming and soothing but also at the same time really striking and unsettling, what I like to call a “calm chaos.”

Even the flyers that you created were sort of public art too, in a way, because you made them digitally, but they were printed out, passed around, put on walls, posted in shops. Why do you think that your work often ends up in a public stratosphere?

I feel like the work is unapologetically itself, and it’s basically just about this woman, highlighting her strengths and her honesty, as well as her insecurity and her confidence. About her not having one more than the other. Creating something that’s complex and complicated, I feel like it just resonates with people.

As far as my background, I went to school for communication design, but I never wanted to, you know, work for a design firm. I just wanted to use this digital medium to express the female form and her complexities. Historically, design and advertisement has been used as a way to communicate an idea in a very clear way. Working graphically, it’s just straight to the point in a way that’s very accessible. Going to a gallery and looking at sculpture or painting can be intimidating. Starting to create the same work, but within a medium that naturally is more accessible. Perhaps our brains are wired to then see it in a certain way. I feel like it can interact with people in a different way than painting.

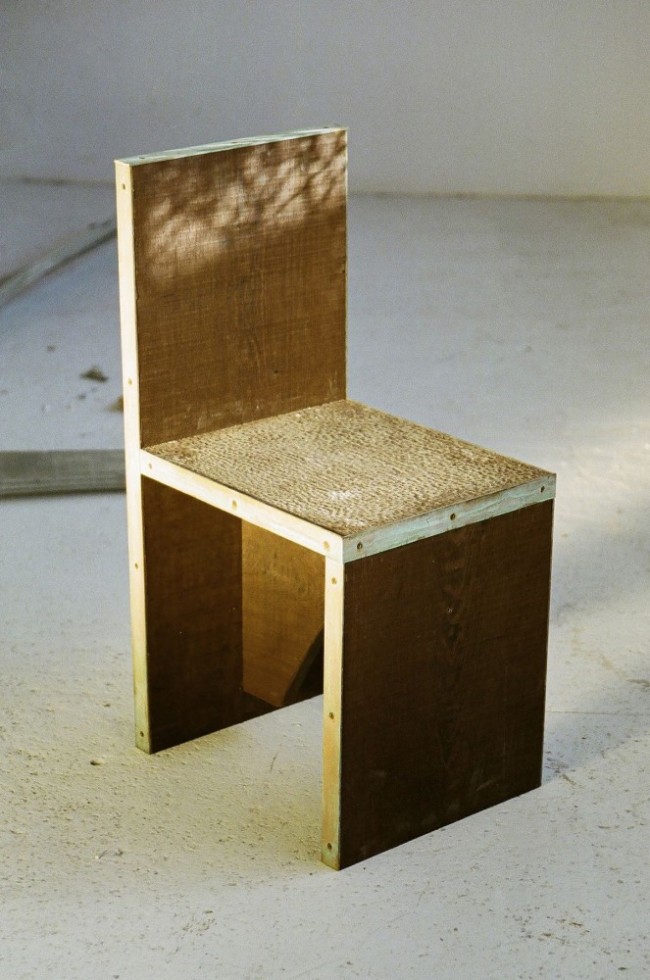

Me Pointing at Me, Pointing at You, Looking at Me by Theresa Chromati. Acrylic, glitter, and vinyl collage on paper, 48 x 78" (2018). Courtesy of Kravets Wehby Gallery.

I feel like the figures you paint are often in motion and in movement, like they’re traveling.

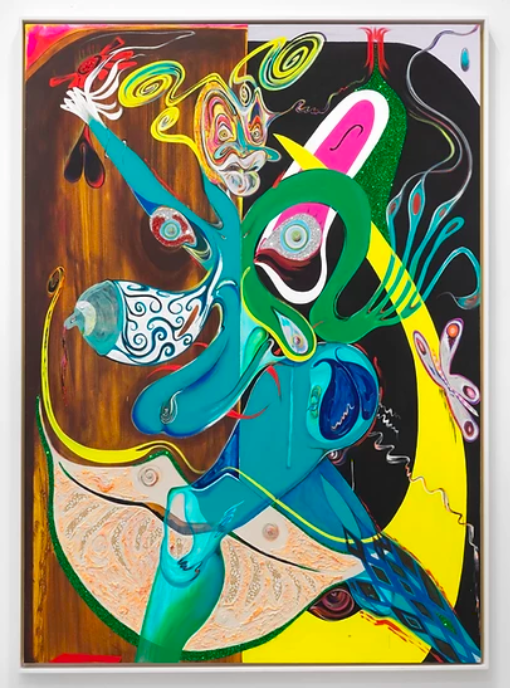

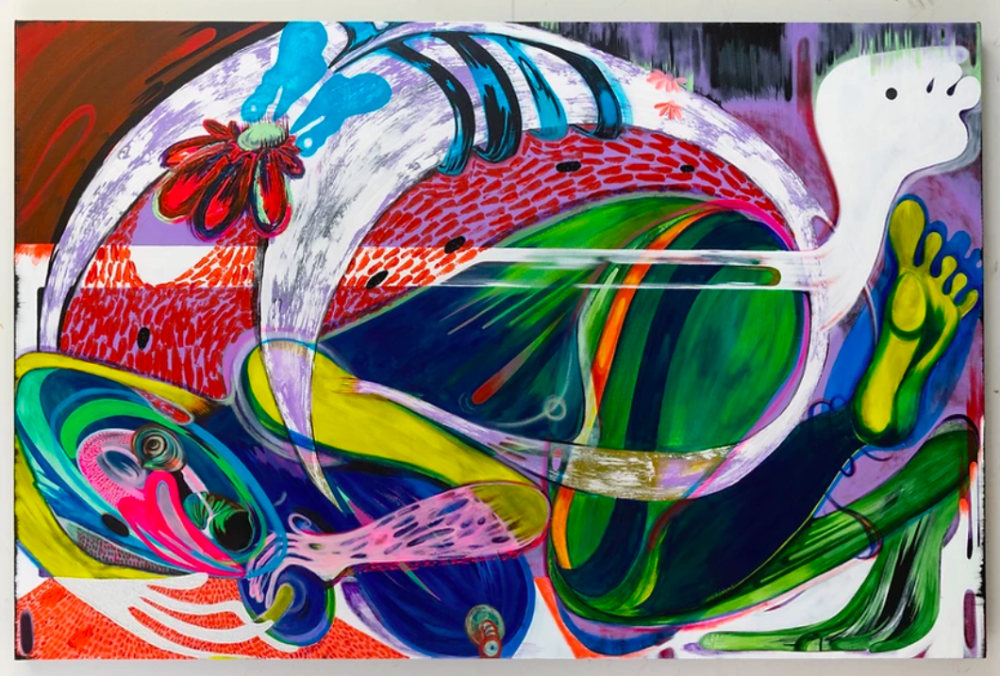

One of the themes in the work is in that when you remain static in life, I feel like you place yourself in a vulnerable space to basically decline. You can still have quiet moments and moments of deep thought without being in a static place, not being able to move forward, whether physically or mentally. It’s really important for me to capture that this woman feels as though she has the audacity to break out of this form. She might not have all the answers or know necessarily which direction, but she has the control to keep the motion going. As a Black woman, I feel as though that’s just what the day-to-day is. And so it’s really important for me to include a lot of vivid color and a lot of beautiful textures and protruding sculptural elements — all these things are building up these complex layers for this woman and showing her diversity, capturing someone’s intensity but also their vulnerability, and showing that you don’t just have to choose one.

In my most recent paintings, the central figures are accompanied by floating eyes and lips, meant to represent the central figure’s intuition. It’s starting a conversation around ideas of women’s intuition. You always have this voice inside you but you don’t always trust it. I feel as though that we’ve been taught not to. So, owning the fact that you have this other form of yourself that’s always with you, and perhaps it’s an energy more aware of certain things. And it’s thinking about, is this voice something that’s inherited like a gift given to us by our grandmothers? It definitely feels like a gift from someone from your past, who perhaps you never even met and who’s definitely still inside you, kinda like a guardian in some way. I don’t believe in angels, but more so spirits.

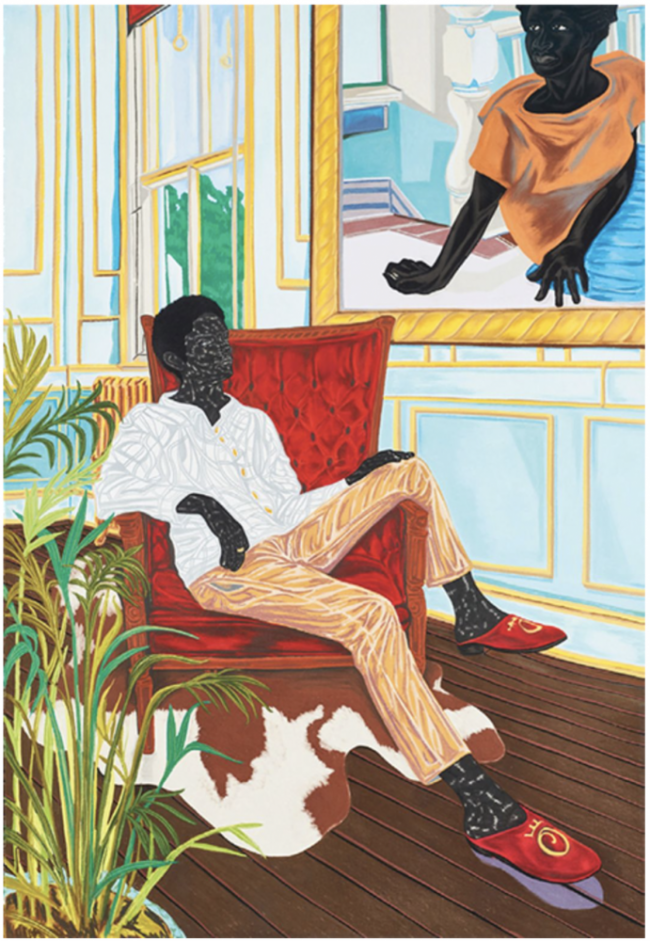

High Love, My Love (diptych) by Theresa Chromati. Acrylic and glitter on canvas, 72 x 120" (2019). Courtesy of Kravets Wehby Gallery.

I think of Audre Lorde, specifically the article that she wrote called “Uses of the Erotic.” She describes the erotic as “a measure between the beginnings of our sense of self and the chaos of our strongest feelings,” and I feel like your work definitely speaks to that. Knowing that there is stillness in chaos and there’s beauty in chaos, and that’s how we tap into our deepest selves and our deepest knowledge of the world. You’re showing that Black women and Black feminine figures are not monolithic. We’re both from Baltimore, and I feel like the perception of our city is often flat. But the world we exist in in Baltimore, and in our Black neighborhoods, it’s not flat. The worlds your figures exist in remind me of being a kid when I used to move and travel through Baltimore, walking everywhere — you know, and Baltimore has a lot of beautiful architecture, and just like randomness, warehouses, the reservoir.

Some of my early work was strongly centered on this woman on a path, which was represented through this checkerboard foundation floor that she’s walking on, and then she was surrounded by these architectural forms, which I saw as archways. I wanted to introduce these ways for the viewer to enter this space, kinda as a portal. I feel like over the course of my practice, those things are still there, but now they’re just not so formal, they’re not so literal. Now these checkerboards are breaking or cracking, or in a whirlwind. These architectural elements are still there, but in this really loose way. It’s about a lot of detachment and putting the pieces together and just still having the audacity to keep moving. Even though your leg might be off. Or this form that used to be something sturdy is now floating around.

You brought up just walking around in Baltimore. I never really made this connection in such a literal way, but I’m from a place that is full of so much life and so much color, but then also a lot of the architectural forms are literally deteriorating. But within that space you still have, you know, these bright beings. Being from a place like that prepares you to realize that there are a lot of complexities. Growing up in that city might’ve been the first introduction to being able to cope with living, and thriving, in proximity to darkness.

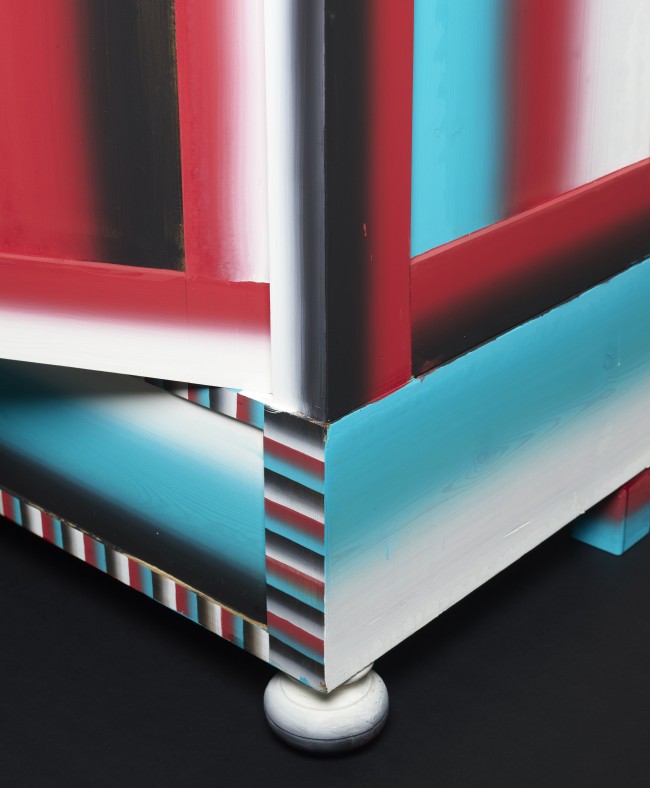

Stepping Out to Step In, an exhibition by Theresa Chromati at The Delaware Contemporary. Photography by Billy Michels.

You’ve spoken on how your figures feel like they’re in different dimensions across time. Obviously, how we come into ourselves is way more complicated than how it’s often framed. I feel like your work is disrupting the idea that we exist in these very linear narratives or according to this very linear sense of time.

Title-making has become really important to me. This show is called Stepping Out to Step In. What I mean by “stepping out,” it’s not necessarily stepping out of yourself to find yourself in someone else, but making the step out of the space that you’re currently in to explore what that is, in order to bring it back to your core. There’s definitely times within some paintings where I’m speaking about taking a step back into the past or pulling this element from the past into your present to help lead you to where you’re going. This idea is why in the paintings there will be super opaque areas, in contrast to super ghostly transparent areas because you can’t really decide which one is physically there, and which one isn’t there. They both hold weight. You don’t necessarily know where you’re going, but that fact that you’re still moving is the most important part.

Do you feel like the figures that you’re painting are multiple people in one?

I feel like they’re multiple energies in one person. So sometimes in the composition, there’ll be like, technically, two or three bodies. But every form is an element of this one woman. The central figure is the dominant figure in the painting. Then for example, the two eyes and the lips that pop up, I see that as a form of the intuition of the central figure. Other times, there will be a smaller figure kinda floating, surrounding the central figure, and I also see that as another form of who she is. So the idea is that one person doesn’t have to exist in one way. These different forms can nurture her and help her expand in different ways. Even with the scrotum flowers I include in my paintings, I see them as elements of her. I see their inclusion as this ultimate balance and this way to express power.

Inbetween by Theresa Chromati. Acrylic on canvas. 48 x 60" (2018). Courtesy of Kravets Wehby Gallery.

Tell me more about the soundscapes that are a part of this show?

There are a lot of contrasting audio elements. I wouldn’t say they’re fighting against each other, but it’s kinda like this call and response. There’s a conversation between the visual pieces and the sound, but also a conversation between the sounds within the soundscape. For example, like, there’s laughter, but then there’s screaming. I’m playing with the idea that there’s not really one without the other. There’s no lightness without darkness. There’s also other elements: words that I find that are important that I recorded myself saying, and they’re all distorted. Elements of a deep sigh, or a deep breath. This soundscape is three minutes long, so it’s quick, but, listening to that over and over again, throughout the course of time, I feel like each time, you’re kinda forced to digest what that is. And so basically, this soundscape and the outdoor element of the show, it’s functioning as a preview and an introduction to the show’s indoor continuation, which opens in September. Outside is definitely more graphic, complex, but a little bit more straight to the point. And then the paintings inside the museum are kinda like the core, like a bottom layer of your skin. More of a safe space for more intimate things to be shared.

And it’s so nice that you can still show work during COVID society.

You know, I went to school in this neighborhood where the Delaware Contemporary is, which is just also crazy because it’s the first place where I started to develop the figures that I’m making now and where I learned the skills to work graphically. It was really a starting place for me. Last year, Kristen Hileman reached out to me about this show. It was her idea to bring the work outside as a part of putting a stamp of the museum like, “Okay, we’re starting over.” Honestly, that’s why I agreed to do it, because it was a symbolic gesture for a reboot.

Abdu Ali is an American avant-garde electronic musician, writer, cultural worker, and multidisciplinary artist who primarily works in sound, dialogue, literary text, and social practice. In 2019 they birthed as they lay, a programming initiative for curatorial projects and community events that foster collaboration, creative action, and reflection.

Images courtesy of The Delaware Contemporary, Billy Michels Photography, Kravets Wehby Gallery, and the artist. Portrait by Lyndsy Welgos.