INTERVIEW: Designer Peter Mabeo On The Power of Human Connections and African Design

Born with a curious mind, Botswana-based furniture designer Peter Mabeo began his practice as a search for something deeper. After ten years of working locally, Mabeo Furniture stepped into the international spotlight in 2006 with a Patty Johnson collaboration and later launched Mabeo Studio, a collaborative design office. Mabeo’s work has found new homes across the world including Stockholm’s Hotel Nobis, Milan’s Hotel Giulia, Hong Kong’s Mercedes Benz Dining Room, and New York's Andaz 5th Avenue Hotel. Despite Mabeo’s global recognition, he retains a deep connection to his native soil and sees his success as an opportunity to rewrite preconceptions about his homeland’s craft. I spoke by phone with Peter Mabeo about his perspective as an African designer in a Europe-centric industry, his connection to the world around him, and his search for life’s simple joys.

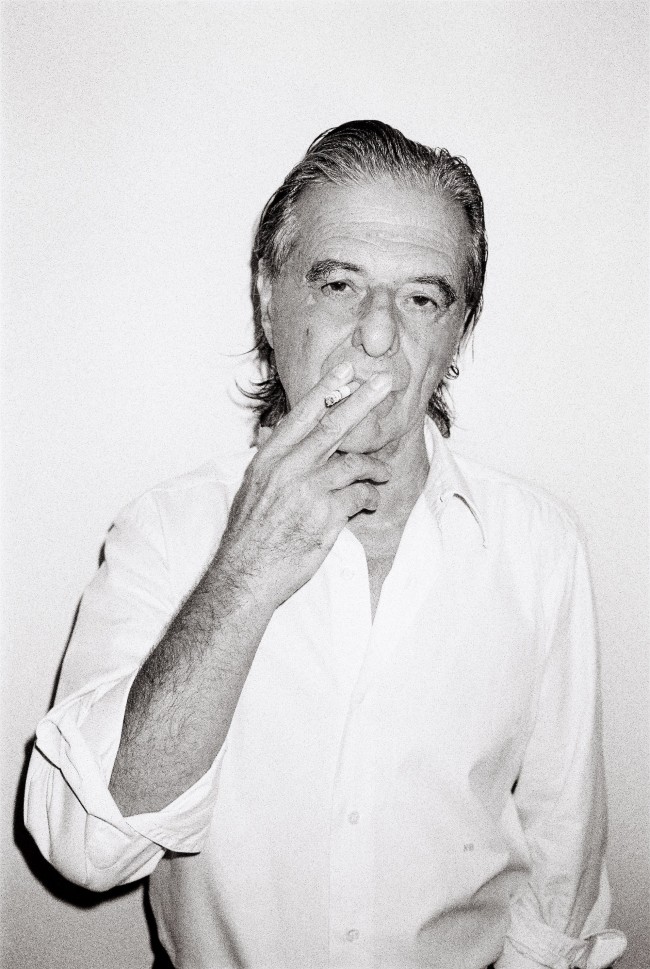

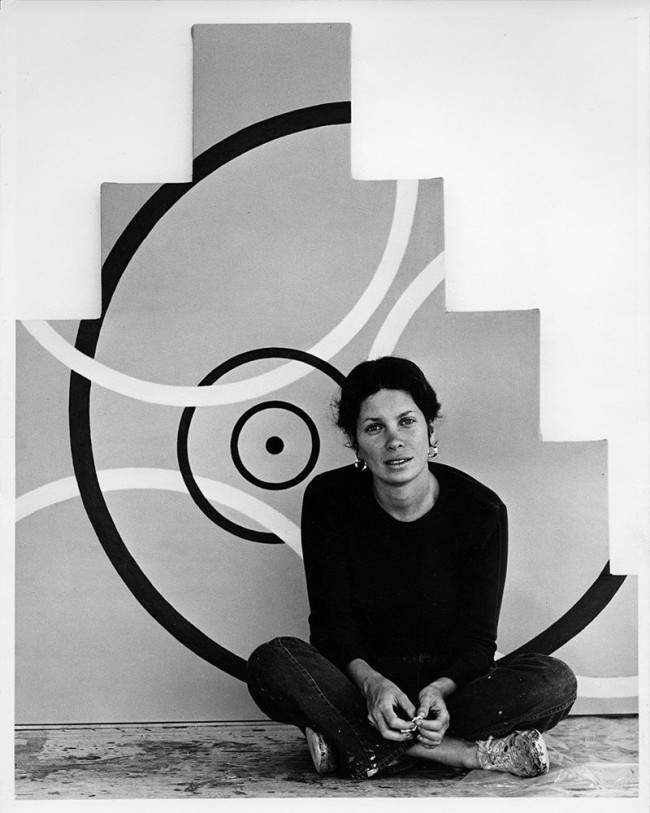

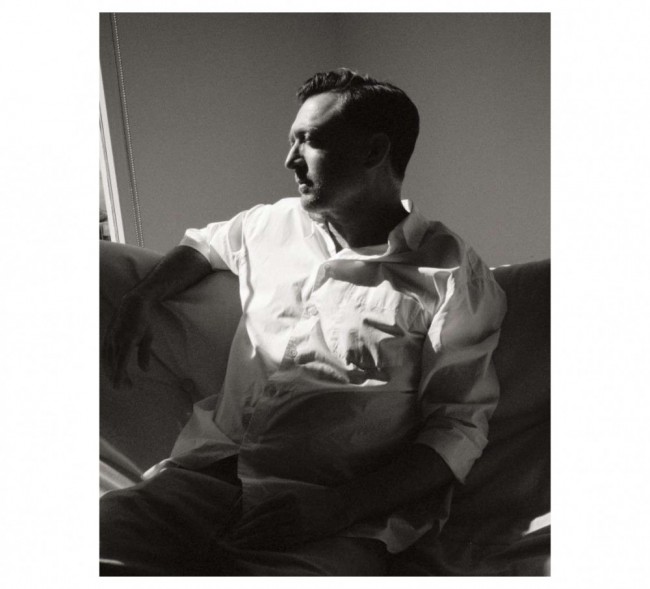

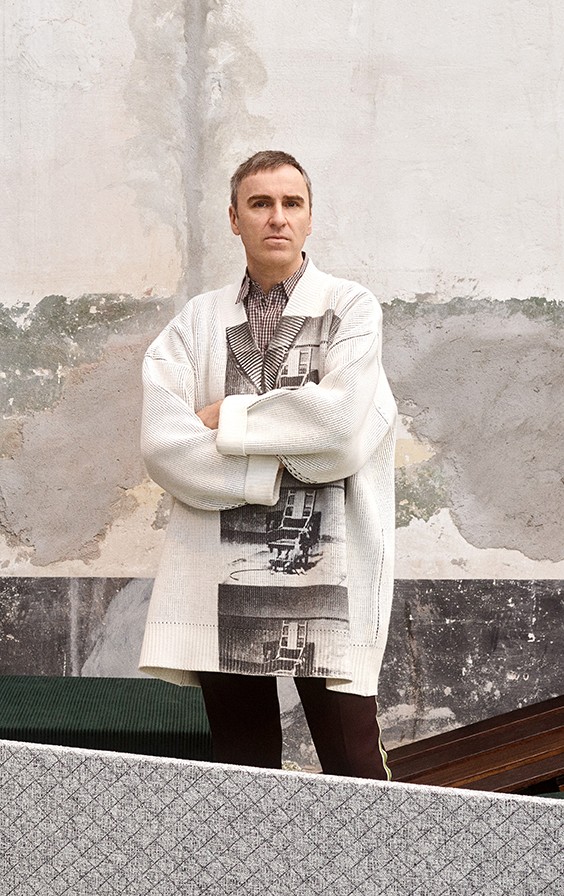

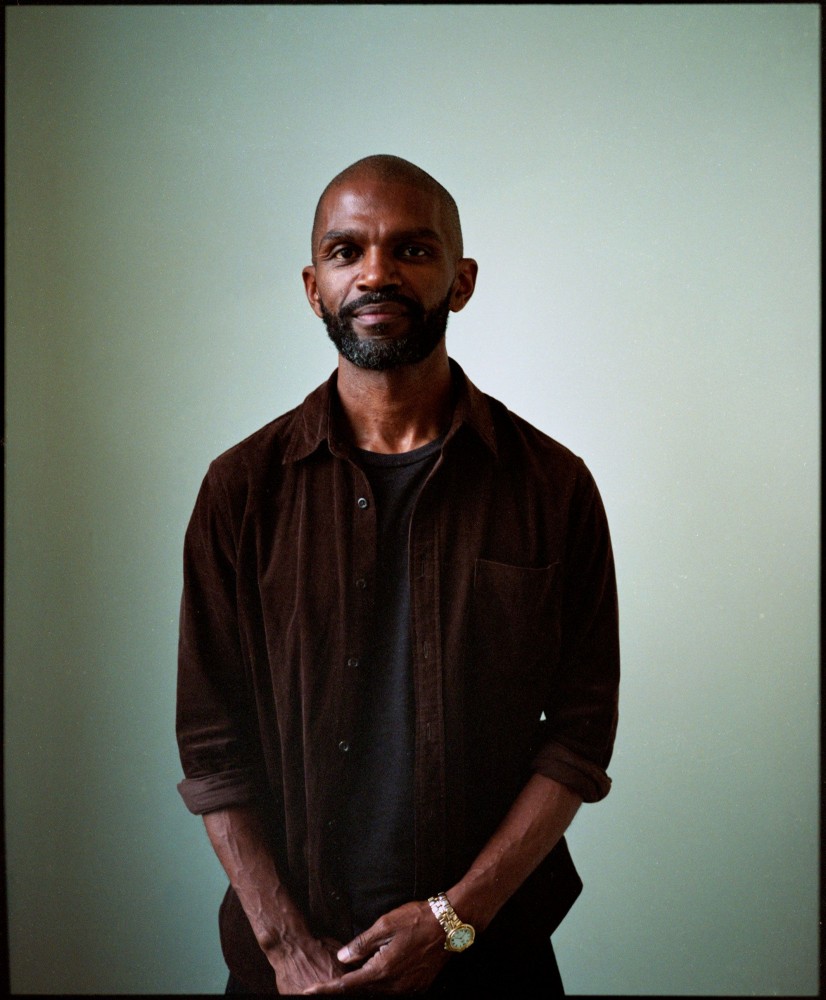

Peter Mabeo photographed by Ruan Van Jaarsveldt. Courtesy of Mabeo Furniture.

Karina Encarnación: Tell me about the birth of Mabeo Furniture and how you got into the world of art and design.

Peter Mabeo: You know when you’ve done things for so long, everything is a bit fuzzy, but I’ll try (laughs). I was never very disciplined in school as far as being overly mathematical or studious, but I grasped things very quickly, and I always wanted to look deeper because the surface seemed a bit boring. I realized that I was looking for the spark or the seed, something that caused other things to come about.

I was in elementary school in the '70s, soon after the independence from our so-called protectorate from the British government. We were kind of being beaten into shape in the sense that our lives were very free, but being introduced to this formal school system, we had to conform to a strict way of existing. I guess I conformed, and I was very quiet. But I was always… kind of rebellious. The birth of Mabeo came about as a way for me to give myself freedom to explore.

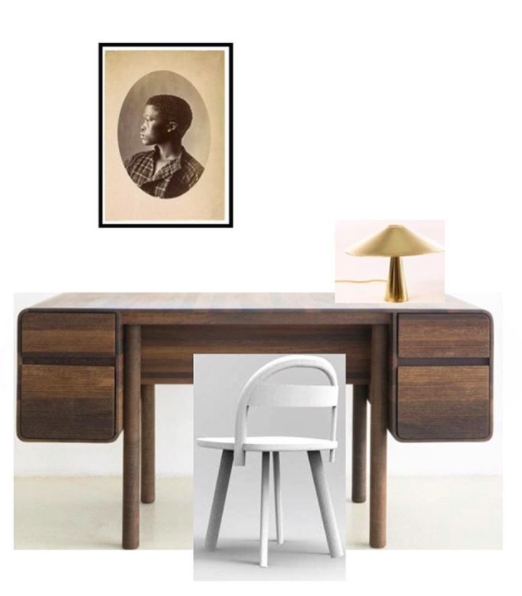

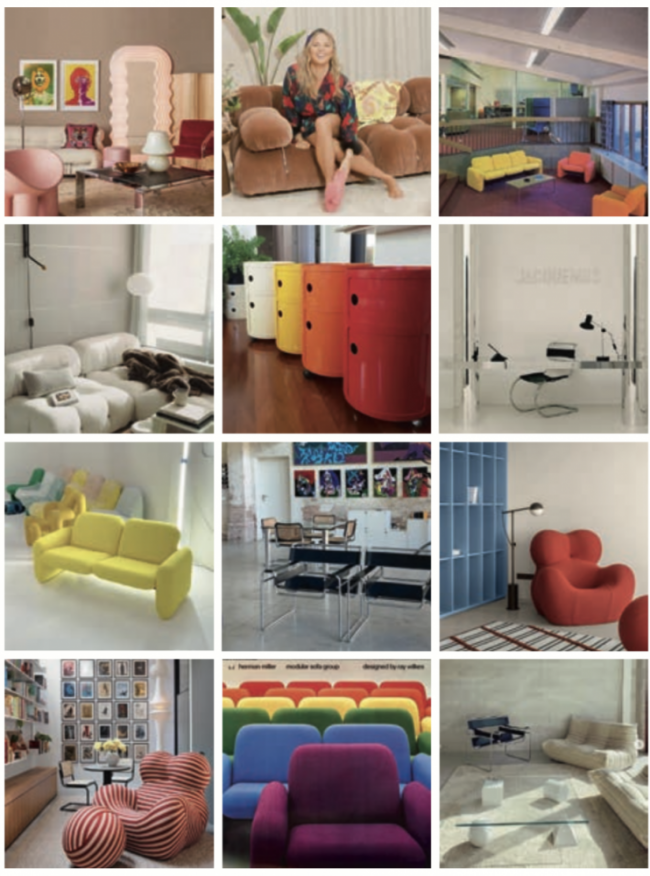

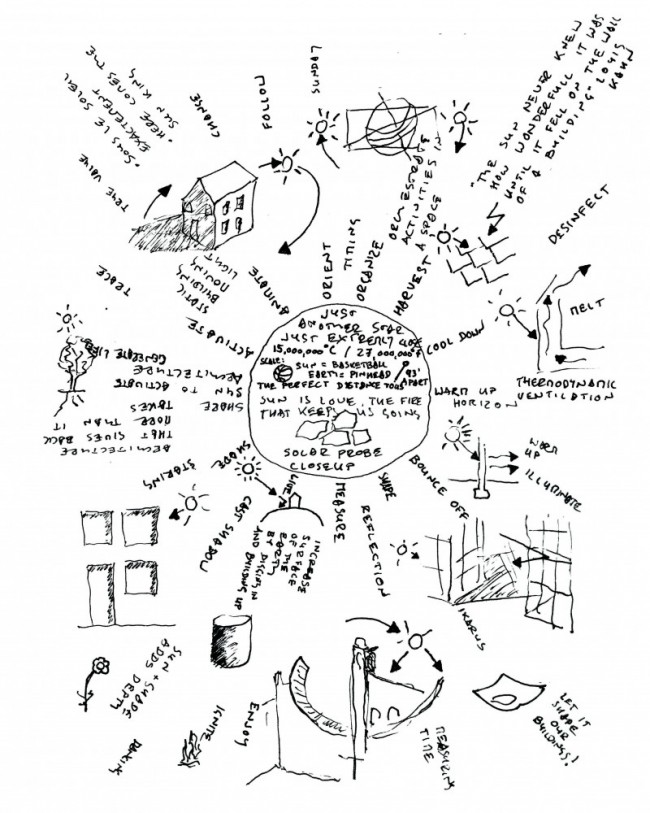

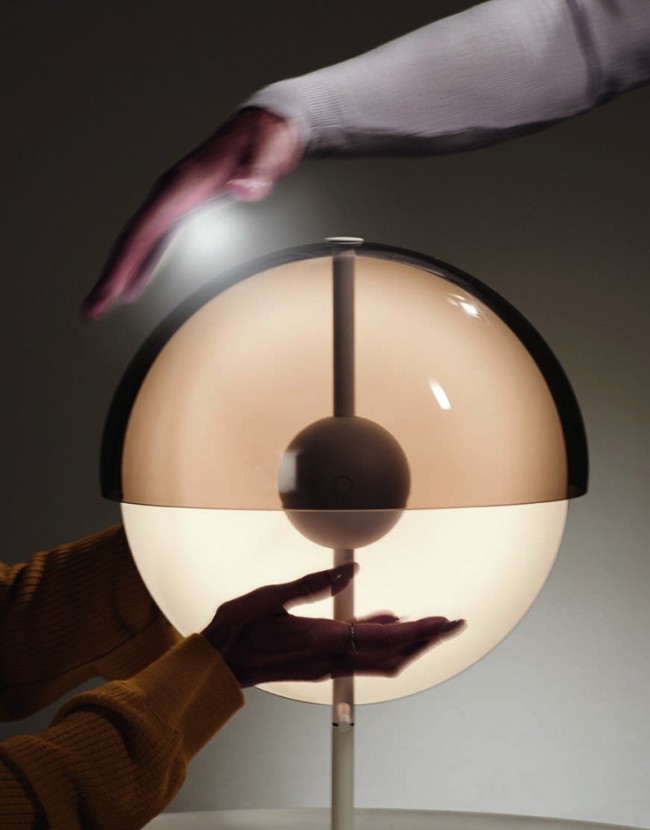

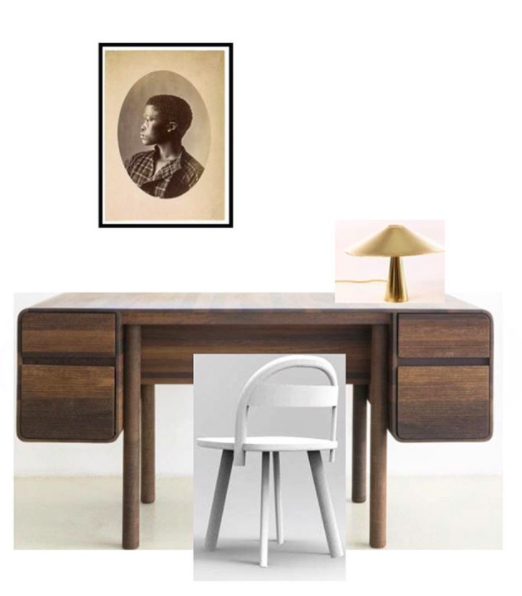

Collage by Mabeo Furniture featuring a prototype for the Oba Chair, the Saale Desk by Mabeo Studio (2016), and the Lebone Table Lamp by Inès Bressand for Mabeo Furniture (2018). Courtesy of Mabeo Furniture.

Have you always been Botswana-based?

I was born here, but I did my last year of high school in Zimbabwe. In the early ‘90s, I went to Miami for a couple of years with my sister, who was on a scholarship in the U.S. at the time. I went there looking for opportunities for further education and ended up enrolling in a vocational school. It focused on the technical aspects of design at a very rudimentary level. I got a little glimpse into the world of design, albeit in a kind of technical sense, and then the rest just came to me. The more I looked, the more I investigated, the more I realized that there were many people who felt the way I did around the world, who saw things the way I did, and who were interested in my context, my viewpoint.

When I was growing up, I was friends with the children of people who came from all over the world to work in Botswana. There were Swedes who worked for development organizations, people from India and Ghana who were teachers, people from the Netherlands who worked in hospitals, freedom fighters from South Africa. So many kids from all over the world who came here to this place that was so kind of barren, who had an impact on me with the stories they used to tell me. Because of that, I developed an interest in interacting with people from my insulated mind, whatever the situation may be.

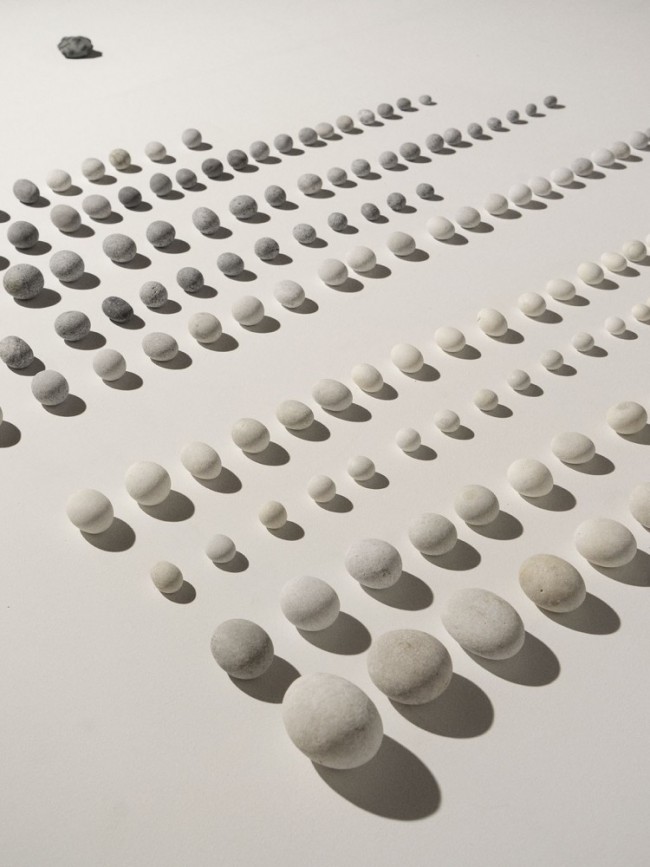

Mabeo Furniture workshop (2019). Courtesy of Mabeo Furniture.

How does design act as a vehicle for connecting with others?

I joke with my friends about how, when I started engaging the world of design, it was as if I was in love. It was like I’d met this person for the first time, and it was so beautiful. I was like, “where have you been all my life?” But then, as time went on, I started to see the ugly side. The side that didn’t quite work in alignment with the beauty that was being expressed. The side that says you have to be somebody of a certain stature or certain background to be able to have access, like in any other industry. But design is almost like a medium of communication. If I didn’t have this, I would not be able to work with different types of people. I don’t like classification and the kind of notoriety that comes with being at the top of your game and the disregard that comes with not being there.

Working within this industry allows me the latitude to work with a craftsperson who’s in a remote corner of the country — I don’t consider it remote, but the world considers it remote — who basically has no affiliation to the outside world. It allows me to challenge contaminated ideas of craft, meaning just making objects for people to take as souvenirs on safari, not actual craft in what I consider to be the respected sense, where the technique is functional and has a reverence to it. It can be very difficult because there’s a lot of geographical and psychological space between the projects that I work with, between the primary audience that I engage with and me, but I’m not just making an object to sell to somebody who doesn’t look deeper.

Matsapa and Ntuka carrying the Sefefo Long Table by Patricia Urquiola for Mabeo Furniture (2015). Courtesy of OMO Creates and Mabeo Furniture.

What drew you towards furniture as opposed to architecture, considering that you’ve interacted with so many people around the world? Usually architecture is placed on a larger international stage whereas furniture is a bit more local and personal. Did you gravitate toward furniture for that very reason?

Funny enough, when I was thinking of what to do as a career when I was younger, architecture was at the forefront because it was the only creative and expressive space that I was exposed to. I just understood architecture and buildings — interiors and furniture weren’t something that I was exposed to until much later on. I ended up realizing that I was interested in things that were more… it’s not even necessarily personal, as in the space, the intimacy, or the connection to a smaller object. It was more personal in the sense that the interaction in the process of making was more personal itself. I’m interested in the bricks and materials at the level of the hand and the eye. The actual ingredients that you put together to come up with something big.

Kika Stool by Patricia Urquiola for Mabeo Furniture (2009). Courtesy of OMO Creates and Mabeo Furniture.

Your first overseas collaboration was with Patty Johnson in 2006, which was right at the start of your international practice. How did Mabeo Furniture shift from a local studio to an international design brand?

Before designing outside of Botswana, I made furniture for local projects. But, after ten years, I just decided to start reaching out internationally, almost like an S.O.S. Patty Johnson was the first person I interacted with to the point where a project was realized. She came to Botswana, and we drove all over, looking at different craftspeople and their techniques. I wasn’t necessarily expecting a project to come out of it. I just needed someone who saw things the way I did from a design standpoint. I needed a second pair of eyes to validate that I wasn’t crazy (laughs).

I was surprised at how much I understood about the world that she was involved in without ever having been there myself, and this is the case with whomever I collaborate with. Like with Patricia Urquiola, for instance, I had never met her. A friend of mine just showed me a product that she worked on, and it immediately resonated with me, and I understood her in a similar way. It’s as if there’s a kind of intuitive unspoken connection. And it’s the same connection I have with the amazing craftspeople whom I work with. There is no fundamental difference really, just a superficial division.

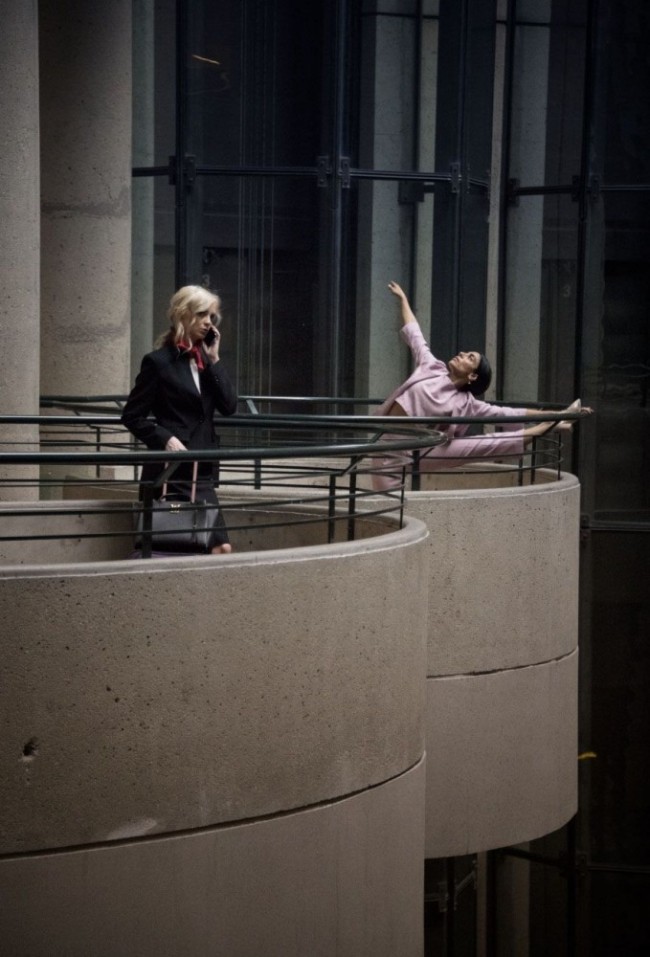

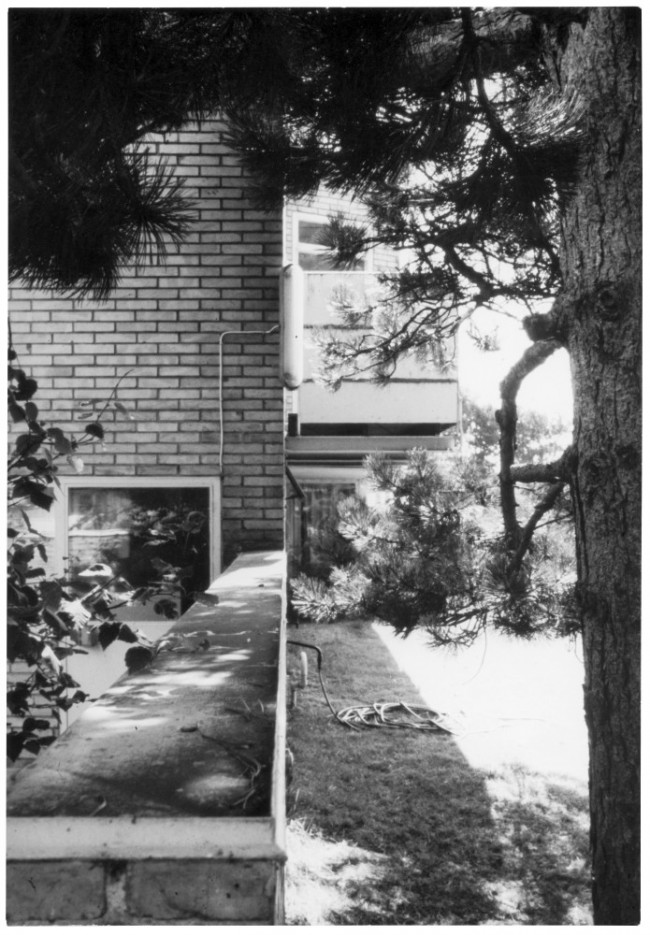

Behind the scenes of Mabeo Furniture’s shoot with OMO Creates for Milan Design Week 2017. Courtesy of Mabeo Furniture.

I notice there’s a strong emphasis on the contributions of the local craftspeople to your practice. What is your relationship with them, and how do they form the foundation of Mabeo?

What I have, and I think it’s a privilege, is the opportunity to work with ingredients of design thinking at the most essential level. To relate with a craftsperson who’s at their most — and I say this with great admiration — the craftsperson at their most basic level. Where they are not part of an industry, or a status mechanism, or an economy. Where they are basically doing what they’re doing as a means of functional survival in a very small but important way. That gives me the opportunity to be at the beginning, at the uncomplicated state.

I love the pieces from the May 2017 collaboration with Inès Bressand, and I read that the collection uses waste metal from the construction industry. Are reuse and sustainability important driving forces in your practice?

It’s always a question of just being practical and using what’s available. I’m in an environment where the artisans aren’t rated as being qualified in the formal sense, but they’re really gifted and skilled at what they do. If the craftsperson is making an object out of material that they don’t have to pay for, then it’s useful, and because I’ve been working this way for so long, it’s just something that’s normal. It’s not necessarily that I’m leaning toward sustainability or something else. It just happens to be what my work aligns with. The idea is not to lose these practices when adjusting to a more formal, commercial environment.

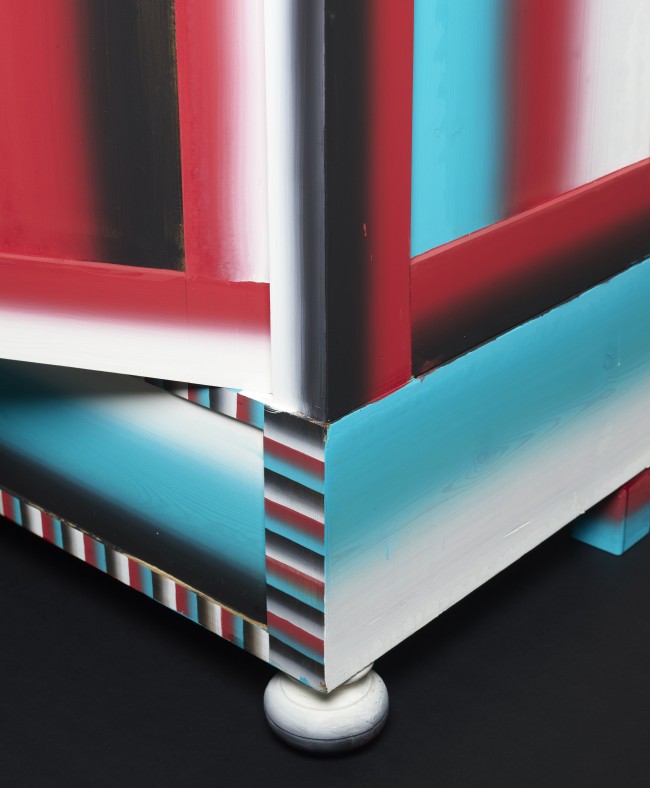

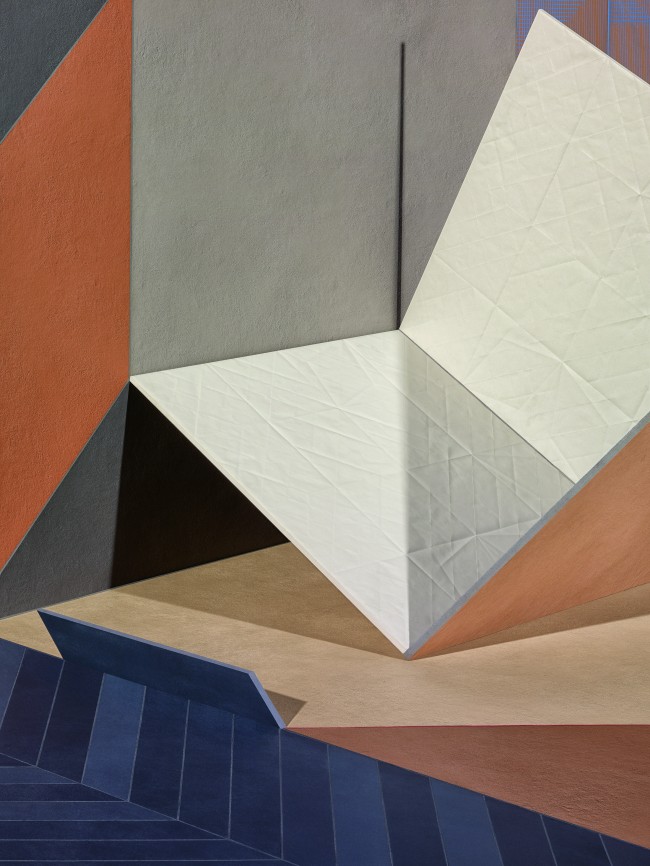

Zezuru Collection by Inès Bressand with Seri Tables by Garth Roberts for Mabeo Furniture (2017). Courtesy of Mabeo Furniture.

Do you think your pieces change in meaning when they’re removed from a local African or Botswanan context and they’re placed onto an international or European stage?

I would say yes and no, and there are positives and negatives on both sides. After going out of my native soil, I realized there’s a restricted way of looking at my type of work: a misrepresentation or misreading of where I come from and the whole continent of Africa. There’s a very small yet controlling part of society that runs the whole economy, education, and development. Unfortunately, I feel like the way it’s being done is not necessarily the best way. I feel very detached from the way progress is happening. I don’t think we’re given the space to express who we are culturally, who we are idealistically, artistically, creatively, and all of that. The broadness of the thought process is being gradually constrained. The products, in the spirit within which we make them, cannot be fully represented in the segmented international context.

However, the reason I went from the basic artisanal level and skipped everything in between to go to Milan Design Week, for example, or to an art gallery or a special exhibition is because that exhibition also cuts out the transitional noise. On an international stage, I can engage with an audience that has a certain interest in what we do. I’m at exhibitions because it’s the only place that I fully interact with our audience. These are places where there is a reasonable proportion of people who can look at our work, and I see, without them even having to talk to me, that there’s a connection. There’s something happening. The idea is to make products or pieces that can contribute in some way of life for someone in New York or Milan. To put this piece in their house and to have a little bit of this spirit, you know? I’m not superstitious, but (laughs) that’s the idea, and hopefully, it comes across. The contribution that we can make ought to go beyond the tangible.

A member of Botswana’s Marok subculture posing with the Sefefo Color Series Stool by Patricia Urquiola for Mabeo Furniture (2015). Courtesy of OMO Creates and Mabeo Furniture.

I think maybe the reason why I gravitated toward your practice so much was the way you photograph your work. I was really intrigued by the pictures of the craftspeople and the artisans that you work with. The furniture is captured through photography in a way that isn’t often seen in commercial design; usually a promotional image for furniture is just, you know, the chair with no one around it on a blank white background. It really made me feel the human connection which is very evident in your work.

Ah, that’s great! That’s the whole idea. It’s not like I have an idea or identity that I want to show. It’s just that when I’m with the craftsperson, and we’re doing something, there’s a special feeling which I feel like should be represented in the product somehow. Because then, the piece itself becomes more valuable — not necessarily money-wise — but because it’s reaching out to people who have an appreciation for that kind of value.

It sometimes feels like you’re waiting. Waiting for people who care about simplicity to come along and waiting to create an environment where the organic, human feeling takes precedence over everything else without it being a conscious effort. It isn’t so much about the intellectual value or the ability to inspire people and all of that. It’s just about simple life, simple ideas, simple interests, and doing special things with special people.

Interview by Karina Encarnación.

Images courtesy of Mabeo Furniture and OMO Creates. Portrait by Ruan Van Jaarsveldt.