GLORIA KISCH: Remembering The Late Artist’s Functional Steel Sculpture

In 1926, a man named Max Stern fled hyperinflation and unemployment in his native Germany, making his way to New York City with thousands of singing canaries rustling, flapping, and crooning in their cages. The birds became lures, nestled into a building on Cooper Square, getting customers into what soon became a pet-store empire.

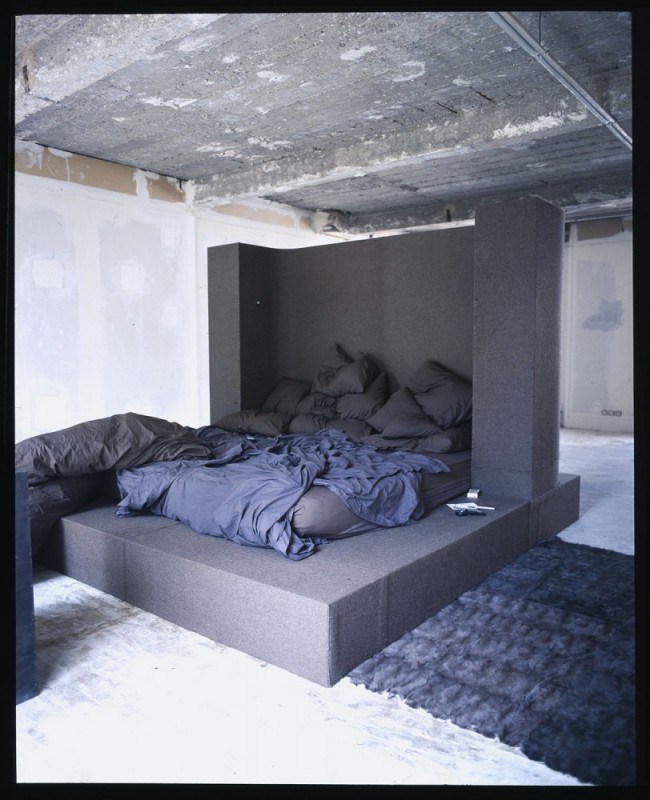

Made from steel in 1990, Max’s Cage is an homage to Kisch’s father, who came to the U.S. in the 1920s with thousands of singing canaries. Kisch kept her own birds at her 40-acre Long Island estate with its own metalworking and welding workshop.

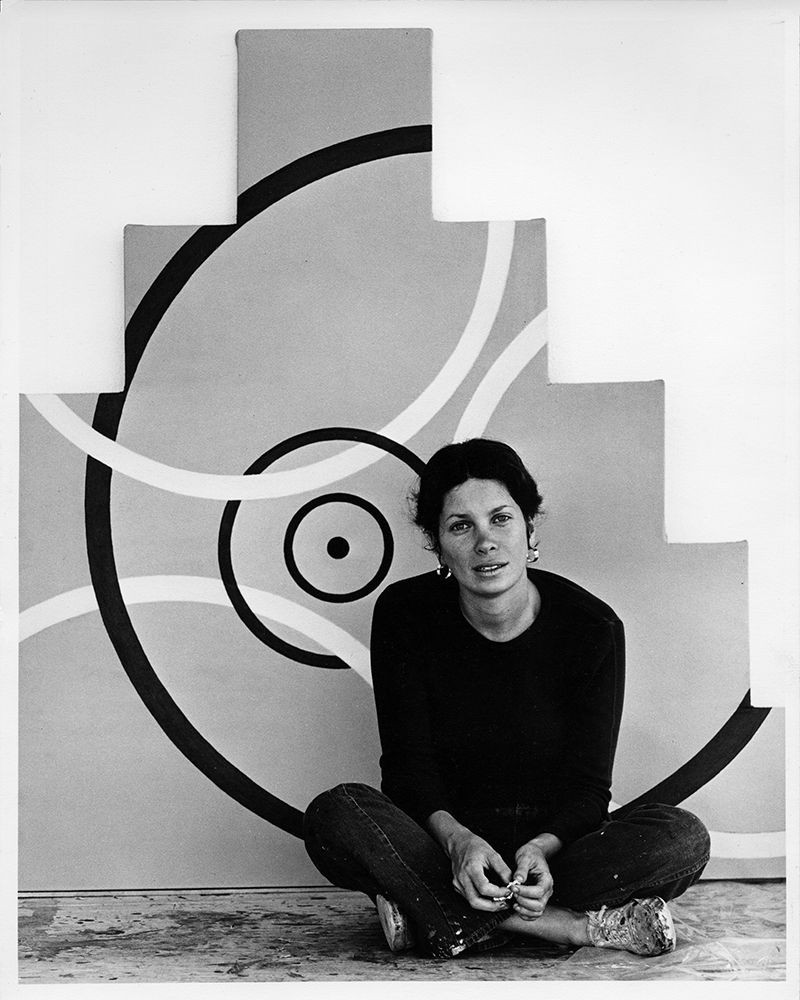

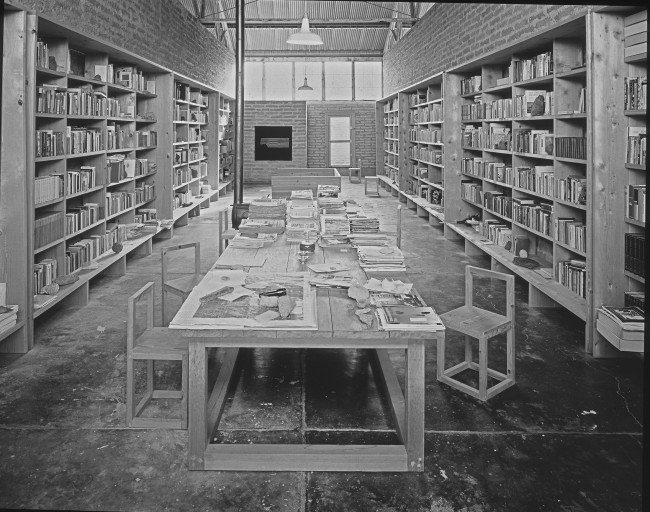

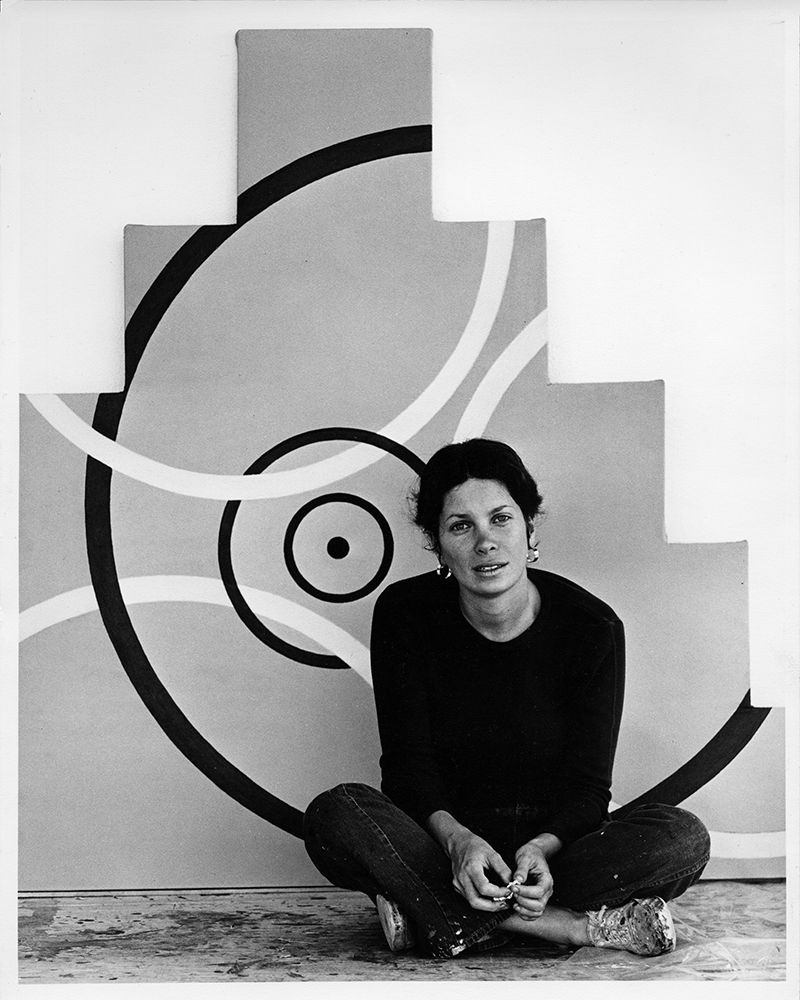

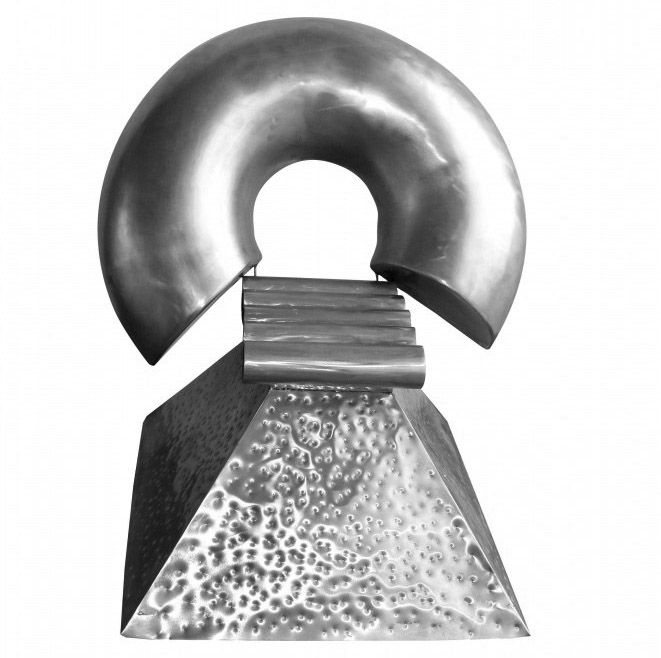

Almost 100 years later, a stainless-steel enclosure sits birdless in the old store, now the dieFirma gallery. Max’s Cage (1990) is a silent siren of its own, made by Stern’s daughter Gloria Kisch and on display as part of the gallery’s inaugural exhibition, ...for Gloria. Kisch, who died at the age of 72 in 2014, remains among the most undersung artists of her generation, and the proof is in the work — her early, boisterous, geometric paintings, for example, or her vast steel bells, fashioned at the turn of the 21st century, stacked and hung like beaded necklaces, large enough to remain untolled by any imaginable wind yet somehow aural when seen.

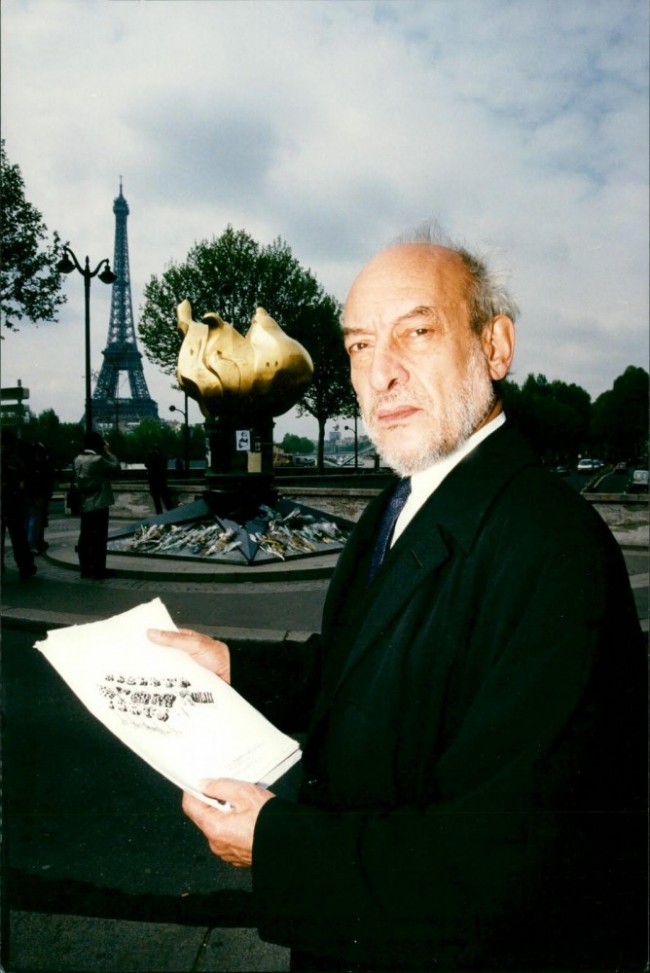

Gloria Kisch with Dessert in State Street Studio, San Diego, California, 1971. Photography by Ned Evans.

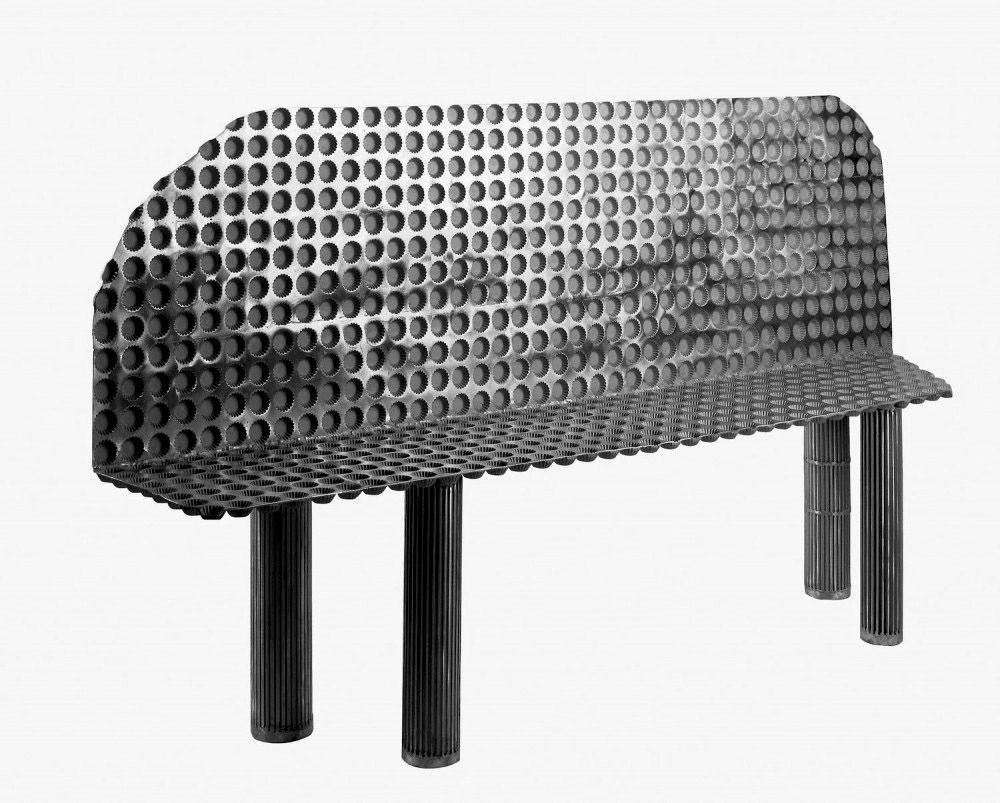

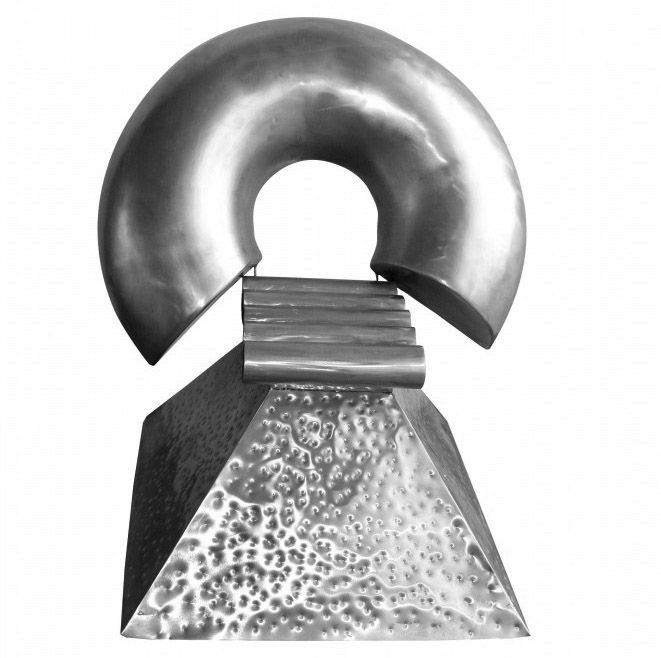

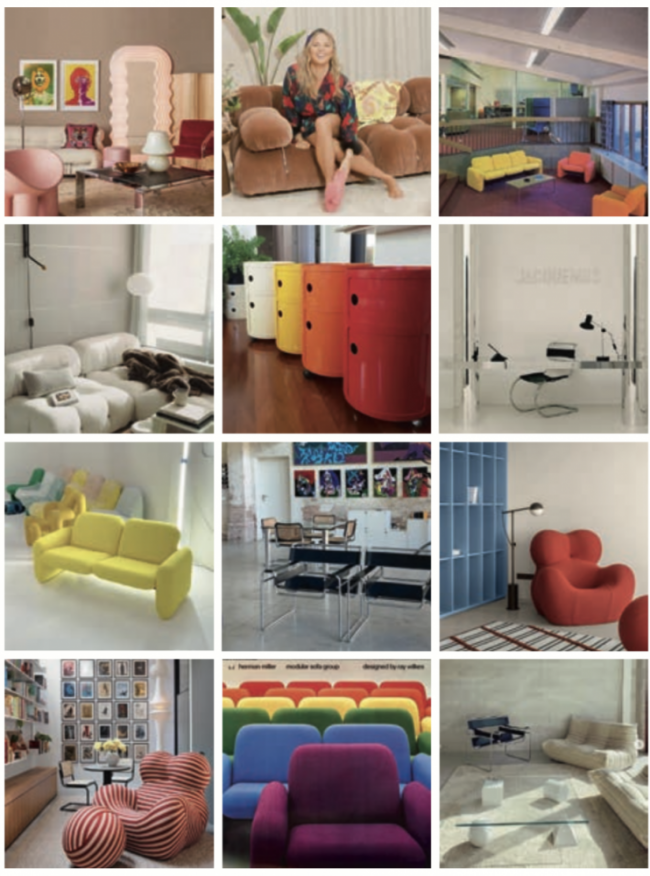

But it’s the cage and a few other functional sculptures, selected by gallery co-founder (and Kisch’s niece) Andrea Stern, that really speak to the future. Doughnut Chair (1991–94) melds the wit of Gaetano Pesce with the materiality of John Chamberlain — there’s something Pop about its rolled-steel seat, and something abject about the way its back, a steel arc like a half-bitten pastry, brings to mind a bedpan. Sweeter is Remembering Sidney (1991), a bench with candy wrappers pressed into the steel seat and back: such an object might make one’s teeth ache with sentiment or back ache with poor ergonomics, but thanks to Kisch’s aesthetic and emotional rigor it escapes such sour fates.

Gloria Kisch’s stainless steel Doughnut Chair (1991–94) is an example of the playful nature present in many of her “functional sculptures.”

Kisch sidestepped a few destinies herself. Max’s pet empire would have allowed his daughter to make a place for herself in the upper middle class, had she wanted it. But did she? She attended the prestigious Sarah Lawrence College, but chose to study with mythologist Joseph Campbell while there; and though she accomplished the assimilationist goal of husband and kids, she cajoled them to go west so that, in 1963, she could attend L.A.’s Otis College of Art and Design — basking in the afterglow of the American Clay Revolution, and about to see the dawn of Light and Space. One can find traces of both movements in the work she made as she transitioned from painting to sculpture after moving to Venice Beach, with its tenuous separation of land and sea. She began making sticks out of sand, and variable gateways and luminous tombs, and “transitional boxes” with eerie, wobbling structures inside rigid frames, and “whisper boxes” that look like 3D Hiroshi Sugimoto photos of Donald Judd works but also don’t resolve in one’s gaze. They blur art and craft, object and aura, what something is and what it does.

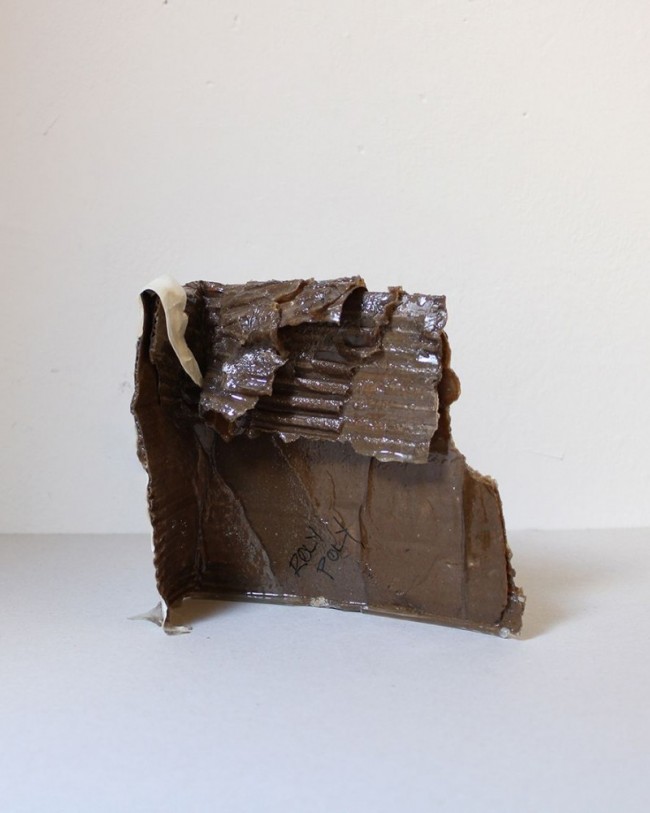

Right: Gloria Kisch, Sliding Down the Mountain III (1990); Left: Gloria Kisch, Sliding Down the Mountain IV (1990).

For reasons political and practical, she showed mostly at women-run spaces like L.A.’s Woman’s Building, though a gorgeous flyer for 1978’s famed Southern Exposure show floats her name among a who’s who of the boy’s club, including Bruce Nauman and Ed Ruscha. In 1981, she returned to New York and set up a studio next to her father’s old store, where she made big, tough work. “She was fearless, determined, a little needy, and tenacious,” Stern told me as we examined a bench Kisch made there, a smooth chunk of steel compressing a coiled-up spring, all impossible potential.

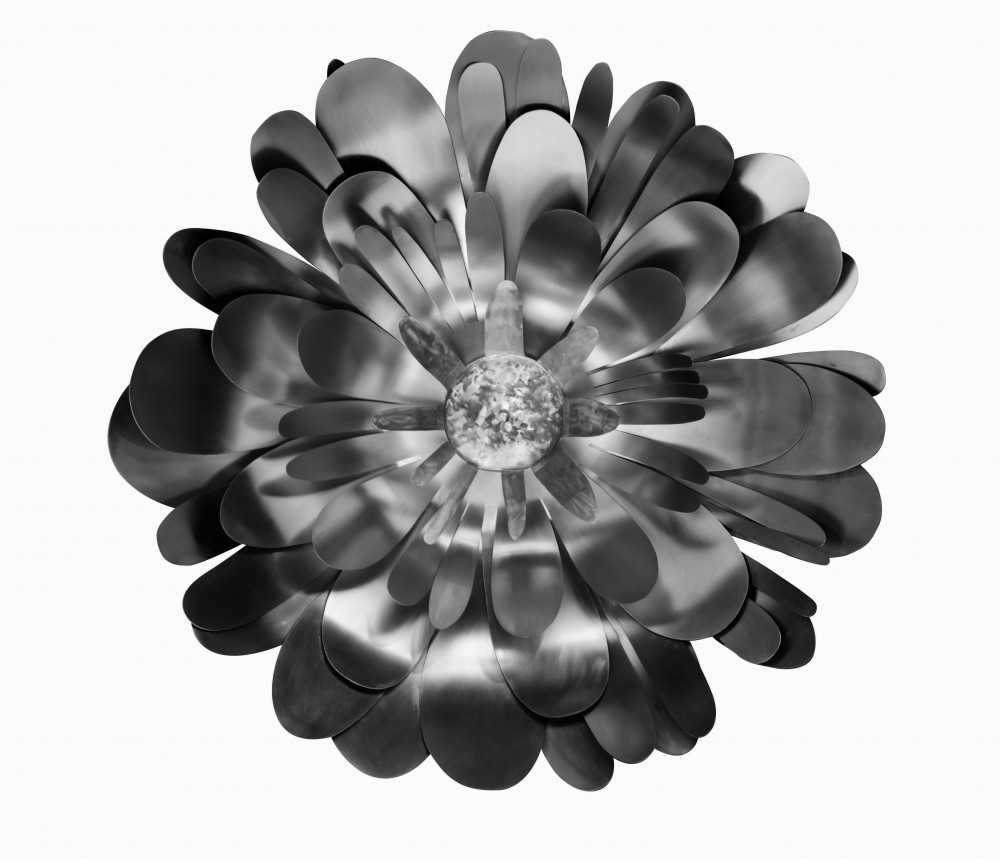

A piece from Gloria Kisch’s metal Flowers series from the 2000s, made from stainless steel.

When the 80s art scene busted, Kisch travelled, experiencing a sing-sing in Papua New Guinea, before moving in the early 2000s to a former duck farm in Long Island. Her later work is less about the built environment and more about takes on the environment itself: reeds and octopi and porcupines and huge flowers, all rendered in shining stainless steel. They are mystical, but never wishy-washy, occupants who escaped the poles of nature and nurture to become themselves. They flew the coop, like her grandfather’s birds, but the cage is beautiful too.