INTERVIEW: Bijoy Jain, Founder Of Studio Mumbai Is Inspired By Air, Water, And Light

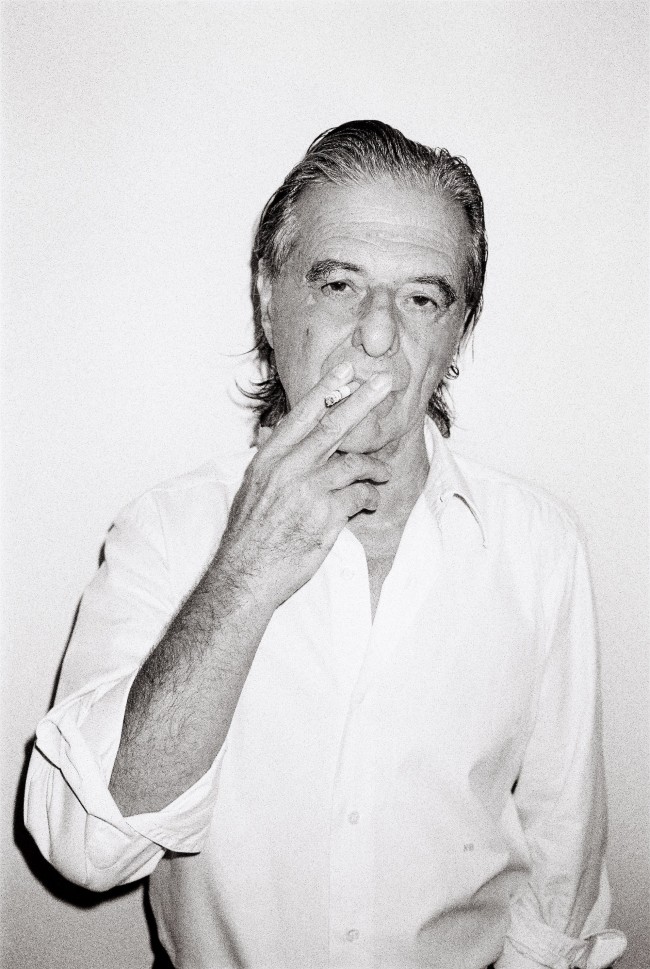

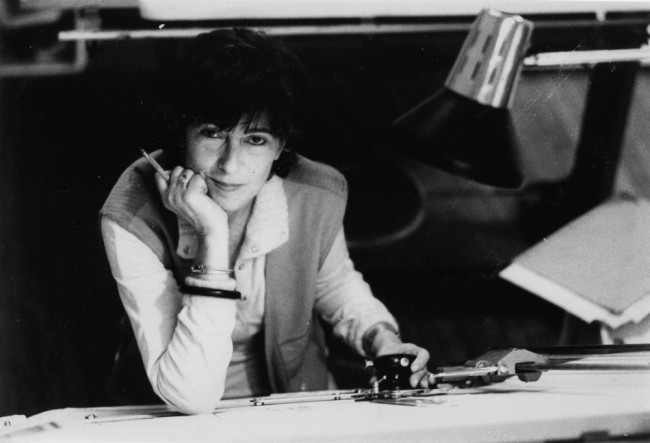

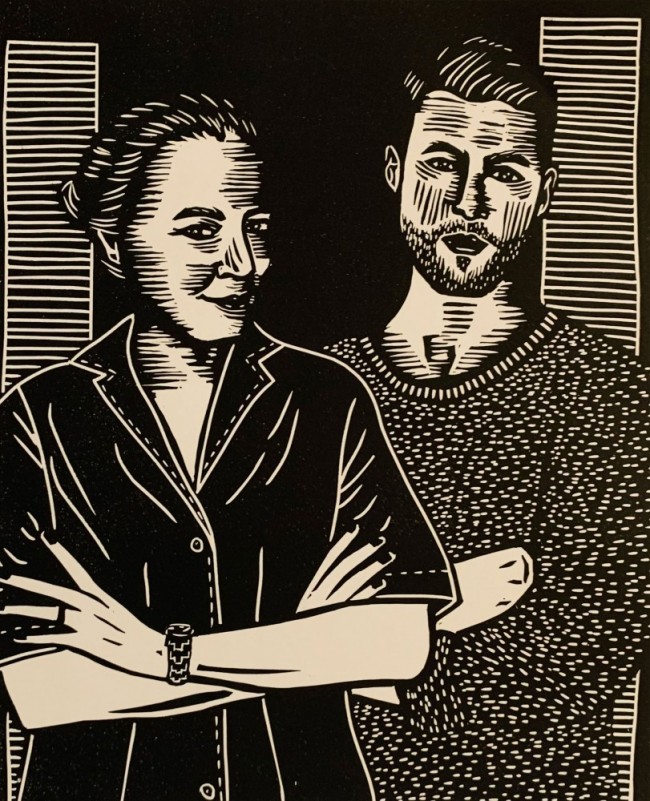

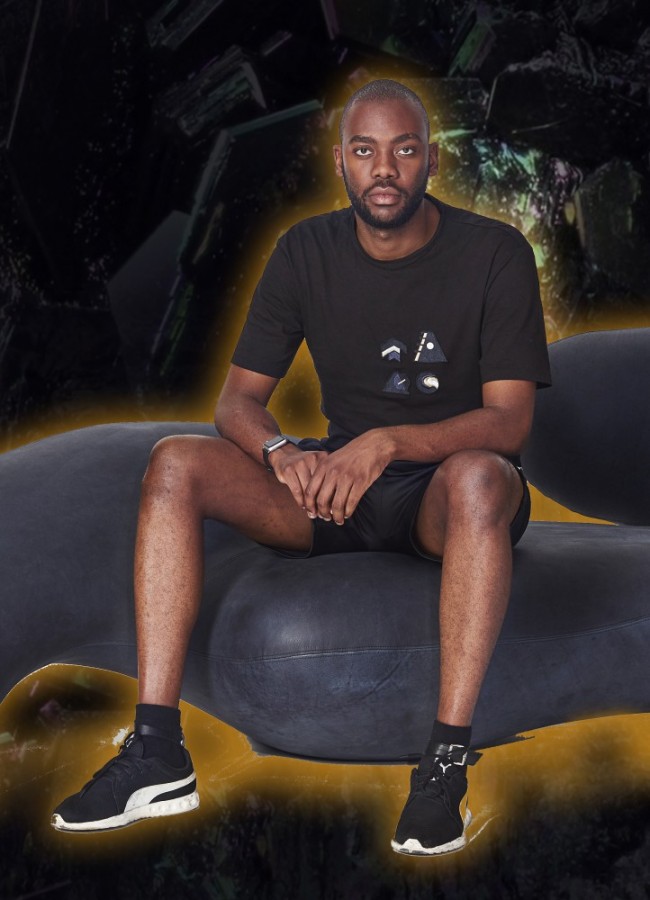

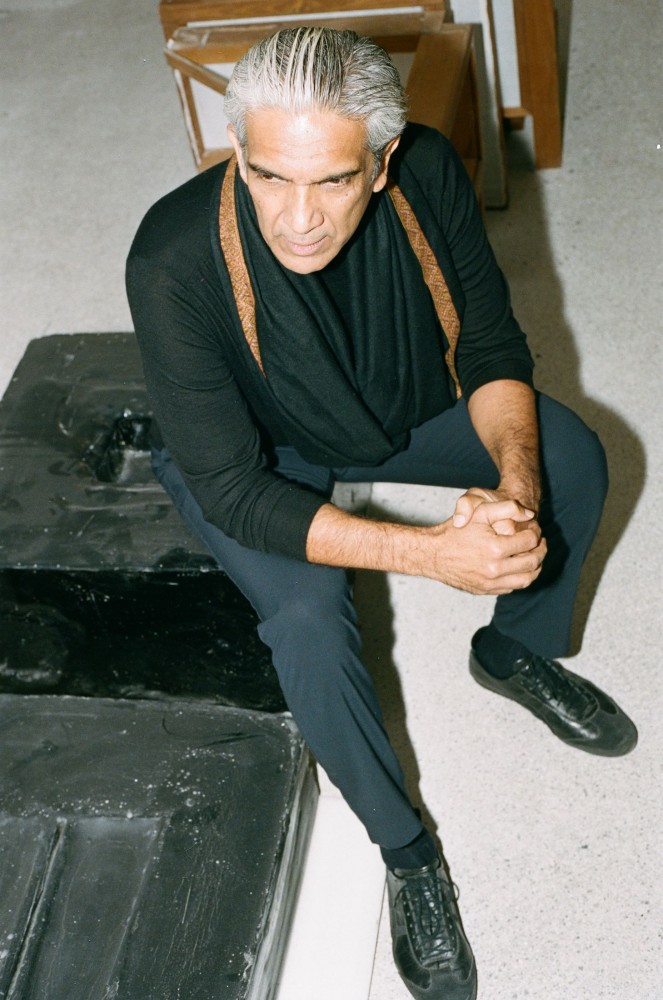

Bijoy Jain photography by Marlon Rueberg for PIN–UP.

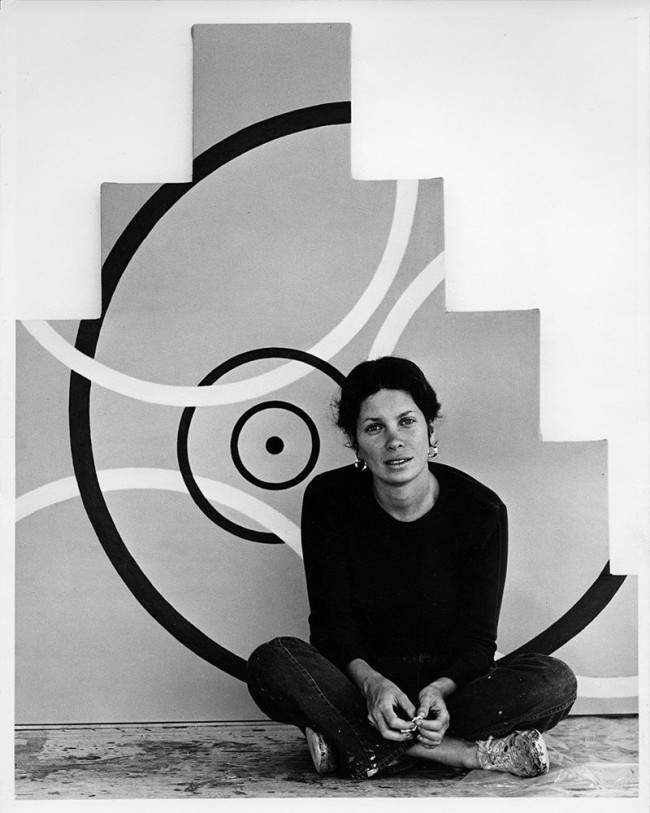

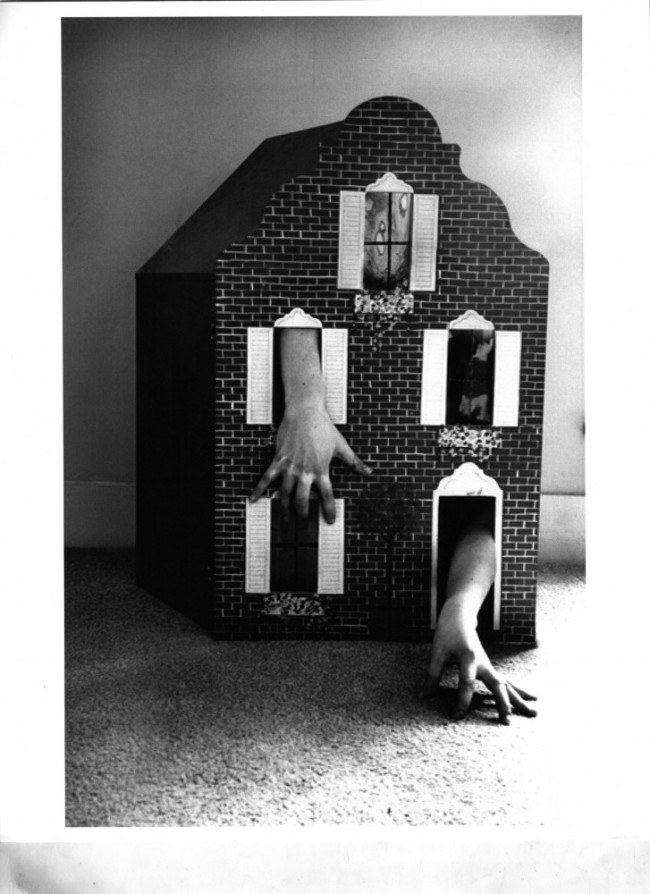

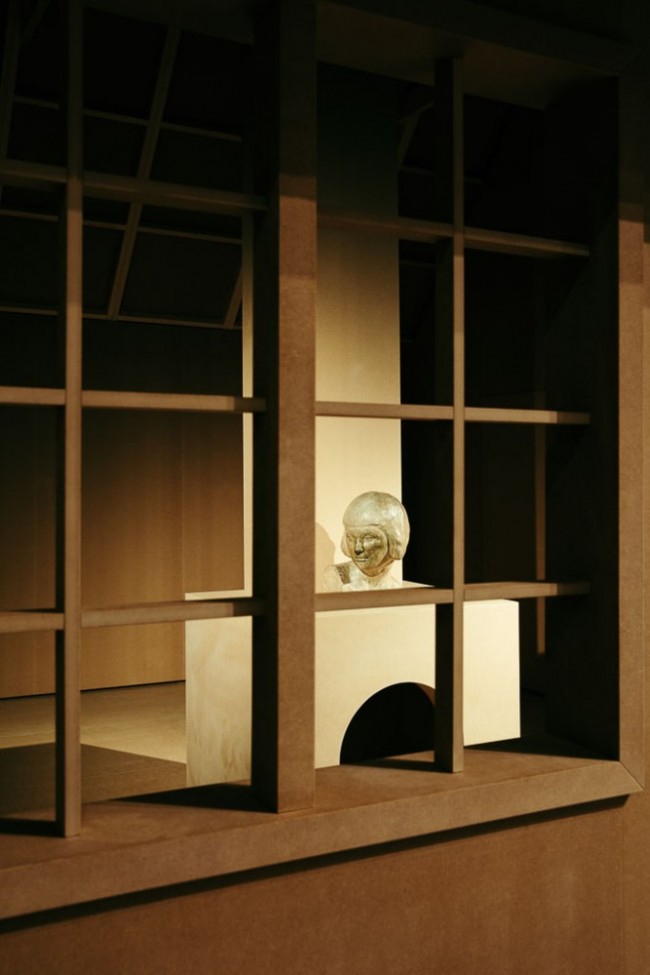

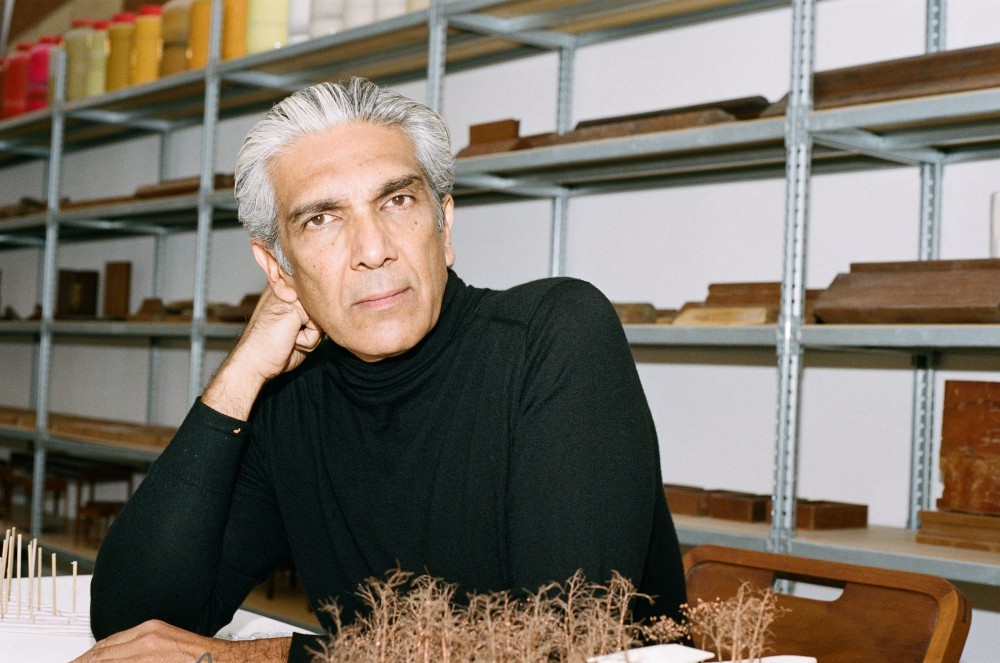

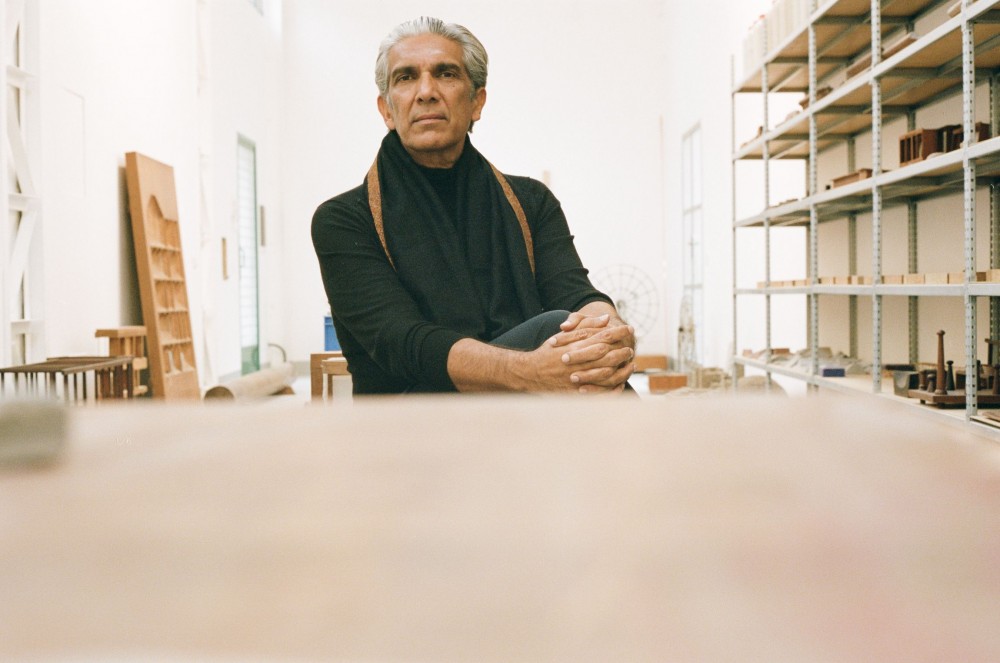

Indian architect Bijoy Jain founded his Mumbai-based practice in the mid-1990s, after a decade of studying and working abroad. But his eponymous firm didn’t come into its own until 2005, after it was renamed Studio Mumbai and transitioned to more of an architectural workshop model, complete with in-house artisans and even a stonemason. In 2010 Studio Mumbai came to the rest of the world’s attention thanks to an installation at the Venice Architecture Biennale. Entitled Work-Place, it showcased the firm’s working method of learning through making. An outlier in an exhibition environment dominated by bio-futurist reveries and the placeless wispiness of what then passed for the architectural avant-garde, Work-Place put the emphasis squarely on hands-on process and local craft. Ten years and several world crises since, Studio Mumbai’s approach seems more à propos than ever, with its deep understanding of materials and the elements — their limitations and their inherent possibilities — in both the architecture and the objects that the firm crafts. Emblematic of that approach are Studio Mumbai’s wood-and-vegetal-fiber chairs, which look impossibly slender and delicate but can in fact bear impressive loads. For this interview, 55-year-old Jain, who was born and raised in Mumbai, took PIN–UP on a tour of his sprawling home-cum-workshop, a former tobacco warehouse in the city’s Byculla neighborhood. When he’s not teaching or traveling for overseas projects, it’s here that he spends most of his time, effortlessly fusing his work and private life into one fluid state of mindfulness.

-

Courtyard view of Bijoy Jain’s studio, a sprawling former tobacco warehouse in the Southern Mumbai neighborhood of Byculla, part of a mixed-use development Jain designed where he also lives. Photography by Jeroen Verecht. Courtesy of Maniera, Brussels.

-

For the past several years, Jain has been working with Maniera Gallery, Brussels producing limited-edition furniture collections. Embassy Cabinet (2016), a study of marble, wood, beeswax, and coconut oil, is one of their earliest collaborations. Photography by Jeroen Verecht. Courtesy of Maniera, Brussels.

Felix Burrichter: I remember your installation at the 2010 Venice Architecture Biennale, which was located between displays by François Roche and Junya Ishigami. It couldn’t have been more different. Not that it felt out of place, but it somehow felt of a different place, perhaps a future place. If you had to compare your practice from a decade ago to now, what is the biggest difference?

Bijoy Jain: The core of the practice remains the same. Back then it was very architecture-centric and project-centric, now it’s more fluid, exploring thoughts, ideas and materials with no specific intention. In fact, Junya Ishigami came to my studio recently, and he was fascinated and curious to see explorations of works with no specific project or purpose in mind. For me, what I am doing right now allows me to be more centered. Architecture can have a way of drawing you in, and then things can start closing in on you. Architecture has its own set of conditions, limits, and boundaries. It can become quite tight, or at least it became quite tight for me. This studio practice allows me to step outside, it allows a space to think and discover. Things are more loose, if I might say. When asked, “Are you busy?” I say, “No, I am occupied.”

Does it ever get hectic in your studio?

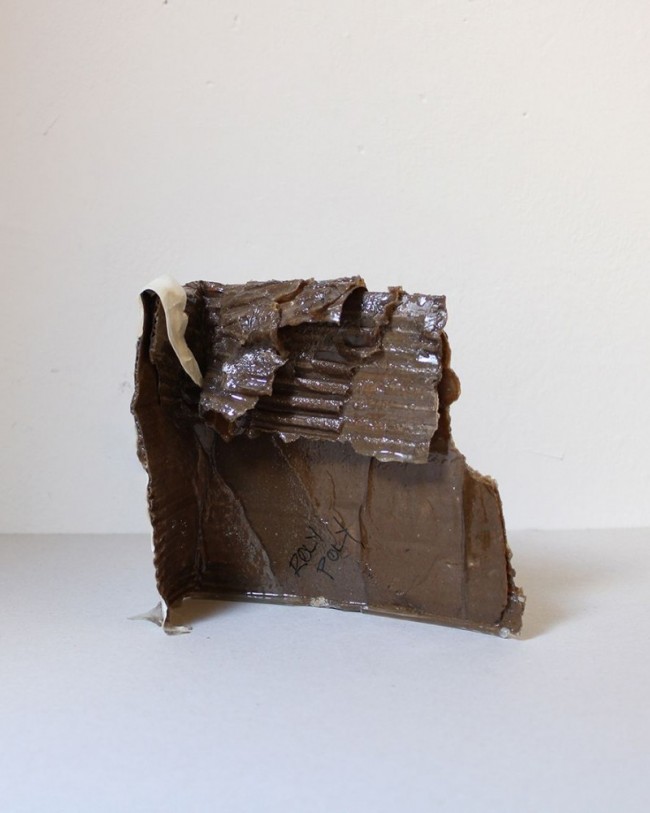

Not so much. I don’t like that way of working anymore. There are just a few people working here right now, a group of architects, artists, and makers. The work oscillates between material studies, architecture, furniture, objects, and things.

-

Furniture works by Bijoy Jain at his studio in Byculla — on the left, a sandstone chair, Gandhara Study I; at the back on the right, a bamboo and woven rope seat, Bamboo Study I (both 2019). Photography by Jeroen Verecht. Courtesy of Maniera, Brussels.

-

Part of Mumbai’s cityscape is reflected in the studio windows hovering over a haphazard collection of found objects and castings that Jain regularly rearranges in the studio, changing their display for inspiration. Photography by Jeroen Verecht. Courtesy of Maniera, Brussels.

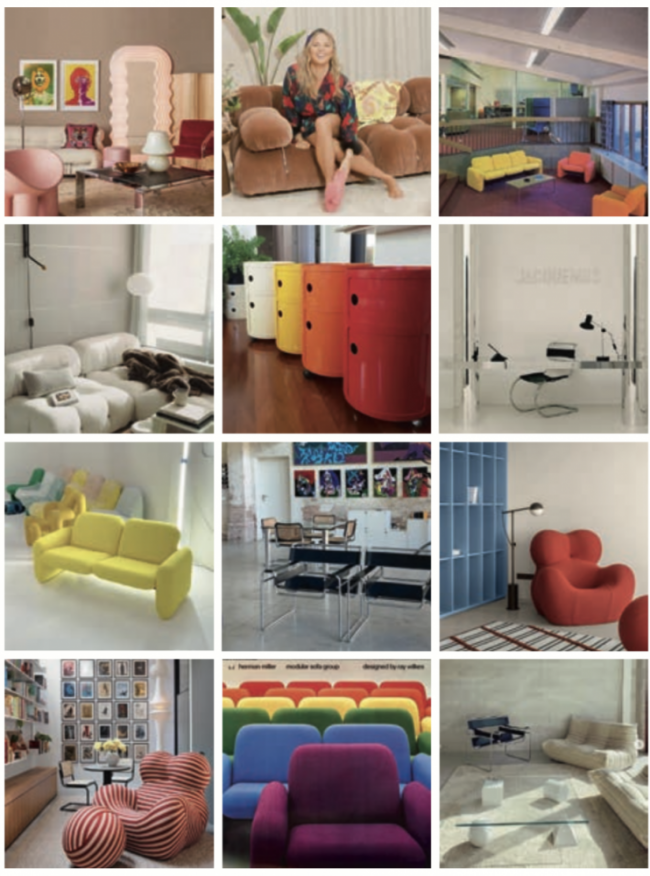

Are you making new pieces for Maniera, the Brussels-based design gallery you work with?

Not specifically. I’m in a continual process of making things. Oftentimes at home, sitting there, I’m like, “Okay, maybe I’ll try something out.” It comes from that impulse. We’ve been working on a project in the south of India, and a lot of the furniture is all in stone. There is a workshop that does incredible things with granite — I think it’s the only workshop of its kind in the whole of India. This is the sort of thing that can then develop into a Maniera project. It’s a really good collaboration with (Maniera owners) Amaryllis (Jacobs) and Kwinten (Lavigne). They visit the studio here in Mumbai, and we travel together oftentimes, just to look at things. Our projects develop from a conversation.

These days you work quite a lot in Milan too.

I have a small studio in Milan as I teach in Mendrisio, which is about 40 minutes away. I’m also building a house in Südtirol, in the northern part of Italy, and have two projects in France. The studio in Milan is very recent. Some of my ex-students are my assistants now. It’s good, as this is what takes me back and forth.

A lush canopy of trees frames the walkway between the street and Jain’s studio, a free-flowing space amenable to his unique practice which effortlessly fluctuates between idea-centric and more project-centric work. Photography by Jeroen Verecht. Courtesy of Maniera, Brussels.

Do you mind if we jump back really far? I’m curious to know why, at age 20, you decided to leave Mumbai to go to St. Louis, Missouri, of all places.

My family passed away: first my brother, then my father and my mother. As a teenager I was a professional swimmer. I had just returned from swimming across the English Channel, in 1983, and three months later my brother killed himself, and shortly after my father died of a heart attack, and then my mother the same. All this happened in a span of two and a half years. I had started architecture school in Mumbai, and I loved it. But after their deaths, everything was completely different. The window I was looking through had changed. I had to get away. And that’s what prompted me to go to the U.S. I was sent to the U.S. at the age of 14 to train for swimming, so it was a return when I came to St. Louis...

But why to St. Louis?

For very practical reasons. I had finished two years of architecture school in Mumbai, and Washington University in St. Louis gave me credits for the time. I wanted to be closer to the coast because I like water, but I happened to end up smack in the middle of America.

What were your first impressions?

The second day we went to Laumeier Sculpture Park in suburban St. Louis, and there I discovered Michael Heizer, Donald Judd, and Richard Serra. That changed everything. It was interesting because in India we have large-scale works like that, but they are anonymous. There are amazing Buddhist caves and a lot of things in the same spirit going back centuries. For me, Michael Heizer’s Double Negative (a 1969 Land Art intervention near Overton, Nevada) is an absolutely fabulous work. Discovering it opened something for me.

Bijoy Jain photography by Marlon Rueberg for PIN–UP.

After St. Louis you went to California.

That was much later, in 1989, 1990. Things weren’t great in the U.S. at that time, there was a big recession, and I was very lucky to get work as a model maker at Richard Meier’s L.A. model shop through a professor of mine. I was there for four years.

You must have been working mostly on the Getty at that time, I assume?

Yes. It was great because Richard Meier’s model shop was quite different than his main of office. You didn’t have to wear a tie and jacket, you could go in a pair of shorts and a T-shirt. It was a very creative space, and a great group of people. L.A. at that time was a different place. In Venice Beach you would still hear gunshots during the day. We just made model after model. Those models were projects unto themselves. They were really impressive. Some of them filled up a whole room, and they just got bigger and bigger. It had a great influence on the way I work. In some ways the shop was independent of the main studio. We did our own thing, it was more tactile. For me, that was the part that I really enjoyed. I remember sniffing so much of that superglue. (Laughs).

Is that when you knew you had to go back to India?

I went to London first, and then returned back home. There were a few reasons. I was very much into yoga at the time, so I decided that if I wanted to practice yoga, I should return to its origin. I also met my wife at the time, that was another reason. And the third was just being home — one doesn’t have to think, you work instead from how you feel. It’s more intuitive and natural. Coming back after a long period of time away, I was making peace with home again.

-

Studio Mumbai’s resident cat takes a reflective pause in one of the studio’s two courtyards. Sunlight filters down through this rectangular oculus and into the interior spaces, connecting ground and sky as well as the natural and built environments. Photography by Jeroen Verecht. Courtesy of Maniera, Brussels.

-

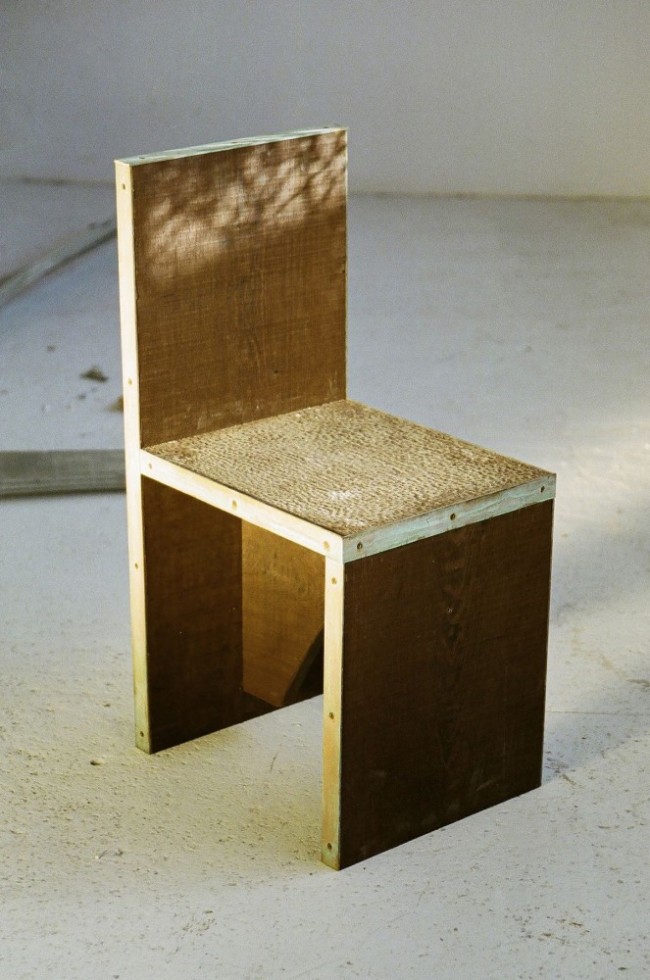

Bamboo Study II (2019) in situ in the studio kitchen, a chair made from bamboo and rope. Photography by Jeroen Verecht. Courtesy of Maniera, Brussels.

-

Bijoy Jain’s furniture is constructed from materials possessing an elemental quality. The Onomichi Console (2019) combines teak and plywood with Japanese washi paper paneling. Photography by Jeroen Verecht. Courtesy of Maniera, Brussels.

Does it ever bother you that, when most architects think of India, they think of Le Corbusier and Chandigarh?

No, it doesn’t bother me at all. I can under stand the outside perspective. The propaganda of Modern architecture has been Chandigarh, simply put.

But would you say that the propaganda of Modern architecture is something you actively work against?

I would not say I work against it. I’m not sure if this answers your question, but when I came back to India in the 90s, there were things that I rediscovered. Landscapes with a distinctly Indian sensibility that had nothing to do with Modern architecture as we know it. It was a big shift in ways of thinking for me. I saw Chandigarh for the first time in 1972, I was very young at the time, so I had no prejudice. I remember seeing other kinds of architecture in hamlets, towns, and villages. I was drawn to all of it. The first time I designed a house after graduating from school, I was drawing it up for six months. The house was in Alibag, in a rural area outside Mumbai, across the bay. When it was time to start construction, I showed my drawings to the local builders and they looked at me like I was crazy. These guys are amazing builders — they have incredible technique and sensibility. It turned out my drawings were useless. I didn’t know how to build, I am still learning to do this. So we put the drawings aside — I tossed away six months’ worth of work and asked them what would be the first gesture they would make. Together with the builders we ended up taking the path that was the gentlest and the easiest way to inhabit the land. These guys knew how to build, they knew how deep to go into the ground, what the material should be, how it should be placed, and so on and so forth. For me it was a big learning curve to become familiar with another way of building.

-

The lightness inherent to Bijoy Jain’s larger practice is exemplified by the delicacy and expressive ness of the designer’s furniture, especially the woven pieces. Like all of Jain’s design collaborations with Maniera, Lounge Chair III (2019), made from rope and either teak or rosewood, articulates a modern and refined reinterpretation of traditional Indian craftsmanship. Photography by Jeroen Verecht. Courtesy of Maniera, Brussels.

-

A wooden stairway detail of Saat Rasta (2011–16) designed by Bijoy Jain, a mixed-use development in Byculla, Mumbai. Located in a former industrial warehouse partially destroyed in a fire, the complex includes Jain’s studio as well as several residential units. Jain’s interest in porosity as well as his sensitivity to light and shadow are both palpable. Photography by Jeroen Verecht. Courtesy of Maniera, Brussels.

You mentioned that you’ve developed a “more loose” way of designing and working. I wonder how that applies when you go to highly codified and restrictive building environments, like, say, Switzerland?

I have built in Japan, for example, which is highly restrictive. We also have restrictive environments here in India. I think that what’s restrictive here might be open in Switzerland or in Japan. And what might be restrictive there could be open here. My interest lies in looking for an opening in whatever restrictive frame work there may be. You could say gravity is restrictive, but it’s not. It is an egalitarian force. We can look at it as some thing that is pushing you down, but you can also look at it as something that can be used as a rocket trajectory.

How do you transmit these ideas to your students?

Freedom actually means finding a gap or an in-between space in a restricted environment. This is really the search. My students have complete freedom to decide on the project, where they want to locate it, how they want to build it, and how they would like to express it. They can dance, they can weave, they can sing, and so forth. They are free in the expression of their work. Freedom doesn’t necessarily mean you can do whatever you want — it comes with responsibility. Leonard Cohen puts it beautifully: “There is a crack in everything / That’s how the light gets in.”

How do you react to your work being led under the label of “critical regionalism,” for example?

This kind of labeling is always going to be present. For me it’s not important — that’s for them, not for me. Even this idea of me working with craftsmen and handwork as part of a larger concept of so-called “sustainability” — I’m just using what’s available to me in the most accessible, most economical, and most agile condition. For me it is about the idea of care. What do I care about? What do you care about? And maybe that is what we are discovering right now — what the value is to oneself. Wellbeing for me is of value. Whatever facilitates wellbeing is what one pursues. I think we are beginning to reconcile with that sense of being again.

The Palmyra House (2005–07) in Alibag, a beach town near India’s bustling capital Mumbai, is emblematic of Studio Mumbai’s approach to architecture as it fully integrates into the landscape. Tucked away in a coconut grove facing the Arabian Sea, the weekend house consists of two two-story timber structures whose façades are predominantly covered in louvers made from the trunks of the local Palmyra palm. The building was a collaboration between Bijoy Jain and local craftsmen. Photography by Hélène Binet. Courtesy of Studio Mumbai.

Do you think you could have developed your practice in the same way if you had stayed in California?

That’s an interesting question, but not one I can answer. Though I can say that having done what I have here in India — and part of the reason I am working outside of the country now — is to discover it’s actually the same everywhere.

How so?

I have discovered that all these places are linked at certain points in time — you experience a building in stone in China, a building in stone in Switzerland, a building in stone in the Himalayas, a building in stone in Japan. They are the same. Materials come into being when we make contact with them. When you shape the earth, there is an exchange of language in materials. If you take Giacometti or Brâncuși, there is a language in the way that they handled things. There is something innate in how materials prompt you to interact with them. It’s common in all cultures. The geography is different, but in the end, it is human contact.

We’ve been talking a lot about structures and buildings, but I would like to talk to you about your relationship with objects. You collect objects, but you also make them. Do you make a distinction between the objects you create and the spaces you design?

For me, scale is about proportion. And size is about dimension. In the end, you are just working with space. I tell my students that the practice of architecture is about making space, not buildings. For me, there is no distinction between an object and a building, it is all space.

But does, for example, a Studio Mumbai chair create the same space wherever it is in the world — whether here in your workshop, or in a collector’s home in Mexico City, New York, or Milan? What is the relationship between space and object?

I think for me the success of a project is when it is able to lose context, when it becomes universal, noncontextual, and is able to exist everywhere. And not just exist, but resonate.

Simultaneously of a place but universal?

Absolutely. When we say “site-specific,” it refers to the immediate context — and yes, I work with my immediate context. But it’s also important to be free of context, and to oppose being too much of a context. So, for example, a piece of furniture for Maniera can be made here, or elsewhere. When I make it here, we use what I find here in the studio. When we make it in the Milan studio, we’re using Milan as a city to explore — to find and develop things. Right now we have two parallel projects going on, in Mumbai and in Milan. The Milan one is exploring glass, for a show at (Venice gallery) Alma Zevi, and here in Mumbai we’re working with bamboo. At a certain point they may intersect. For our winery project in the south of France (a 2018 competition win to redesign the Château de Beaucastel), the project draws from the Côtes du Rhône region — it takes the land, air, and water, the idea of terroir in the process of building as in the way of making wine. It is about water. My work, at root, is about water — the presence or absence of water, or the search for water.

Bijoy Jain photography by Marlon Rueberg for PIN–UP.

Is this the former professional swimmer speaking?

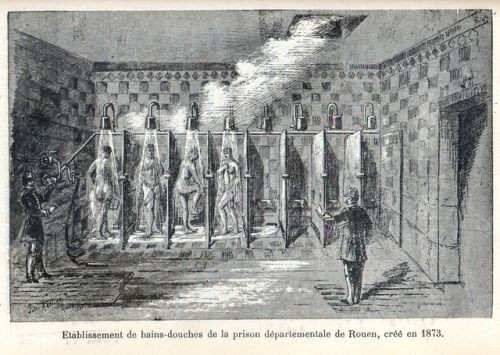

(Laughs.) No, this has nothing to do with being a swimmer. Water is the one thing that has sustained us as a palimpsest of civilizations. If you go back through civilization, you will find that the absence or presence of water was at the core of what established inhabitation of space. All of my projects include a vessel of water, something that can, in anticipation, contain or collect water.

This applies to absolutely all your projects?

Yes.

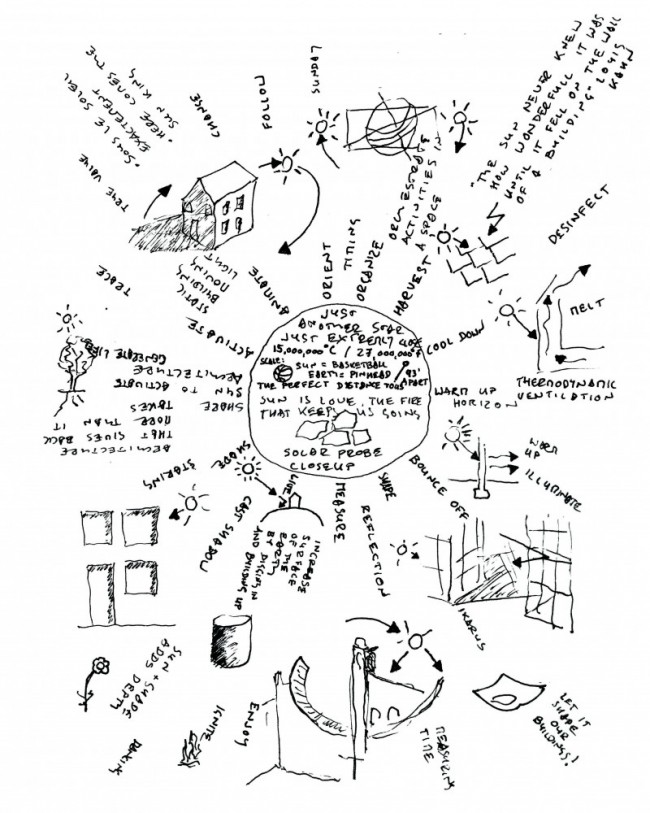

This issue of PIN–UP is dedicated to another elemental force, the sun. What role does the sun play in your work?

For me, the three materials that are important and central to my work are water, air, and light. This is the basis for making everything, this is what the human body requires. The sun and the moon are at the core of this idea. For me it is about how close we can make things that we inhabit to mimic the human self. I am referring to being as in a sentient being, not in a metaphorical, philosophical, or spiritual way. I want to use light and shadow as resonance, as energy. For me, what is fundamental in the pursuit of architecture is for it to have the capacity to breathe.

Would you describe yourself as nostalgic?

No.

Are you romantic?

Yes.

How so?

(Long pause.) It is the relationship between the sun, the moon, and us. There is a romance in this relationship.

Interview by Felix Burrichter.

Portraits by Marlon Rueberg.

Studio photography by Jeroen Verecht. Courtesy of Maniera, Brussels.

Architecture photography by Hélène Binet. Courtesy of Studio Mumbai.

Taken from PIN–UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.