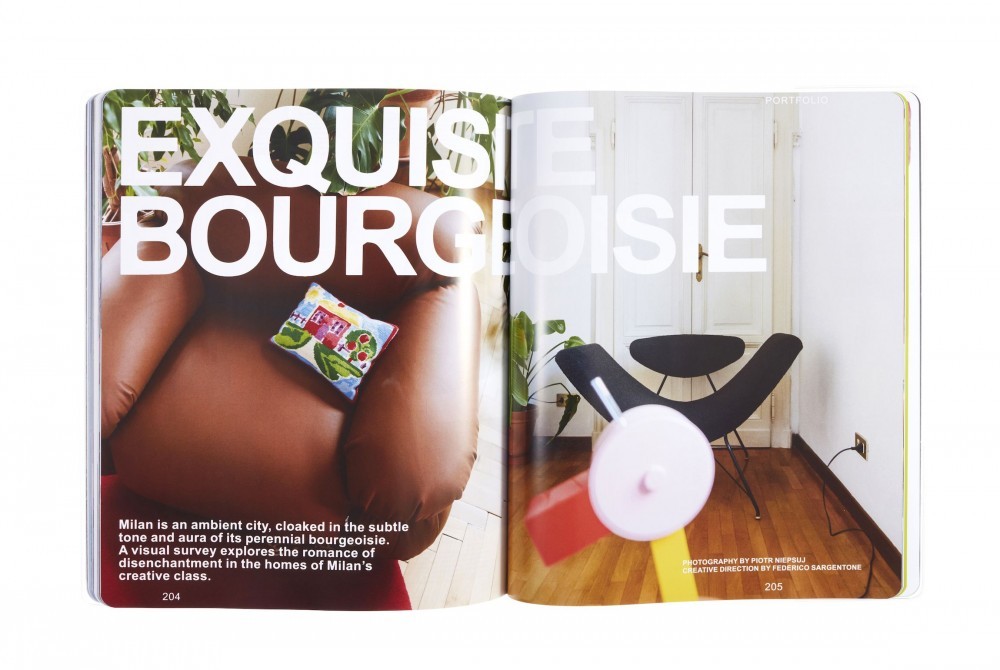

EXQUISITE BOURGEOISIE: The Romance Of Disenchantment In The Homes Of Milan’s Creative Class

“That you who are reading this are reading it is almost proof in itself: proof that you belong.” German theorist Hans Magnus Enzensberger wrote this passage in his 1976 Marxist-adjacent essay “On the Inevitability of the Middle Classes.” For Enzensberger, the bourgeoisie could only be defined in terms of what it is not, as the class that is neither nor.

Gianfranco Frattini’s Sesann sofa and armchair (1970/2015). Available through Tacchini.

To claim a univocal definition of the bourgeoisie is, indeed, a paradox, as the term has been twisted and mystified throughout history — first, gaining political status through the French Revolution, then translating into the subtle form of lifestyle throughout the 20th century. Inevitably, with the developments of late capitalism and the rise of the immaterial economy, which complicated the direct relation between product and capital, the bourgeoisie itself became a condition, rather than a class.

-

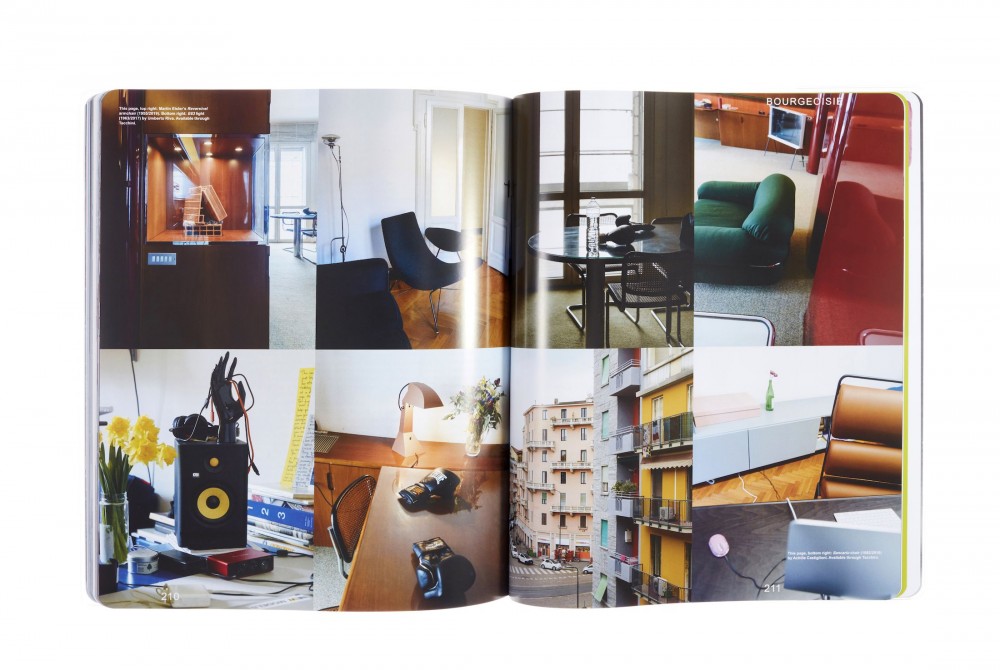

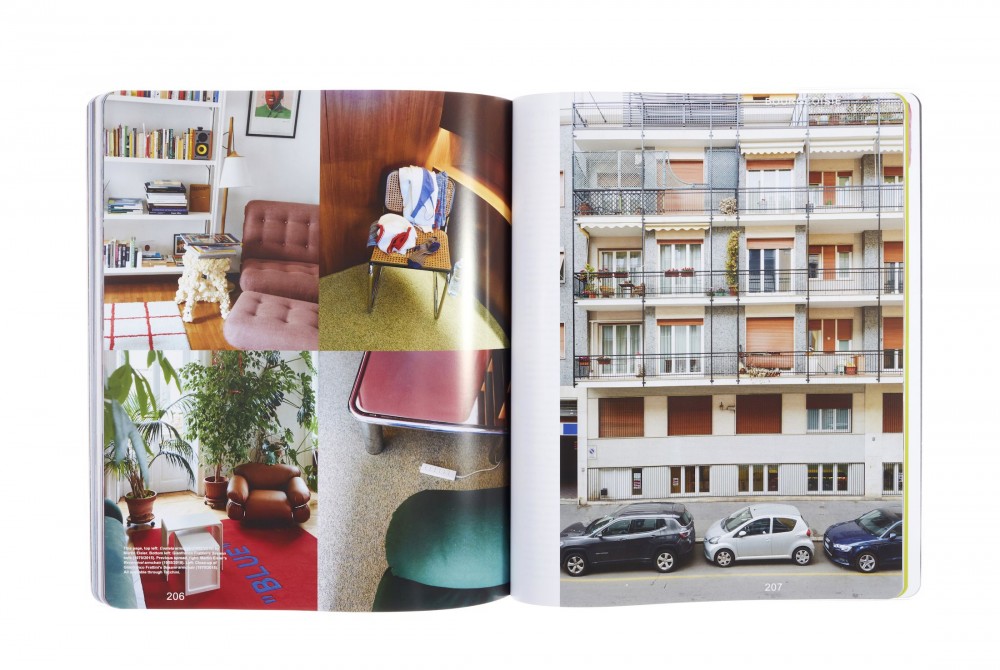

Photography by Piotr Niepsuj and text by Federico Sargentone in PIN–UP 30 Spring / Summer 2021. Spread photographed by Luke Libera Moore.

-

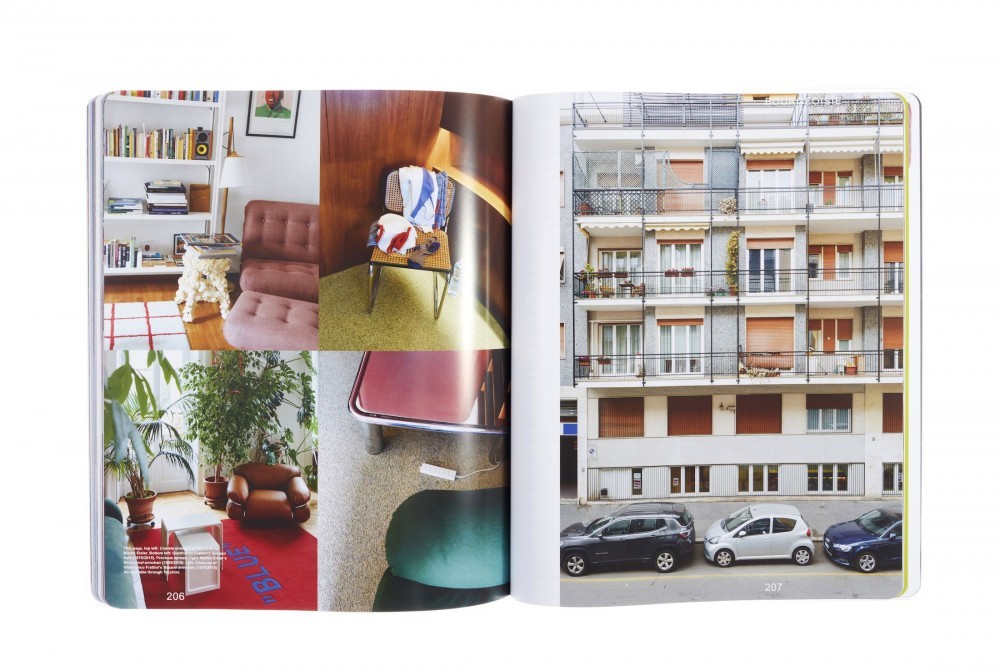

Photography by Piotr Niepsuj and text by Federico Sargentone in PIN–UP 30 Spring / Summer 2021. Spread photographed by Luke Libera Moore.

“Class,” “classic,” “classy”: the semantics around the bourgeoise ideal comes as no surprise with connotations of elegance, luxury, grandiosity, and, again, class (as in chic) reinforcing the historicized belief of the upper-middle class as the only arbiter of taste, the gatekeeper of dignity, the ultimate ruling social group — something that critical theory has defined as a cultural hegemony.

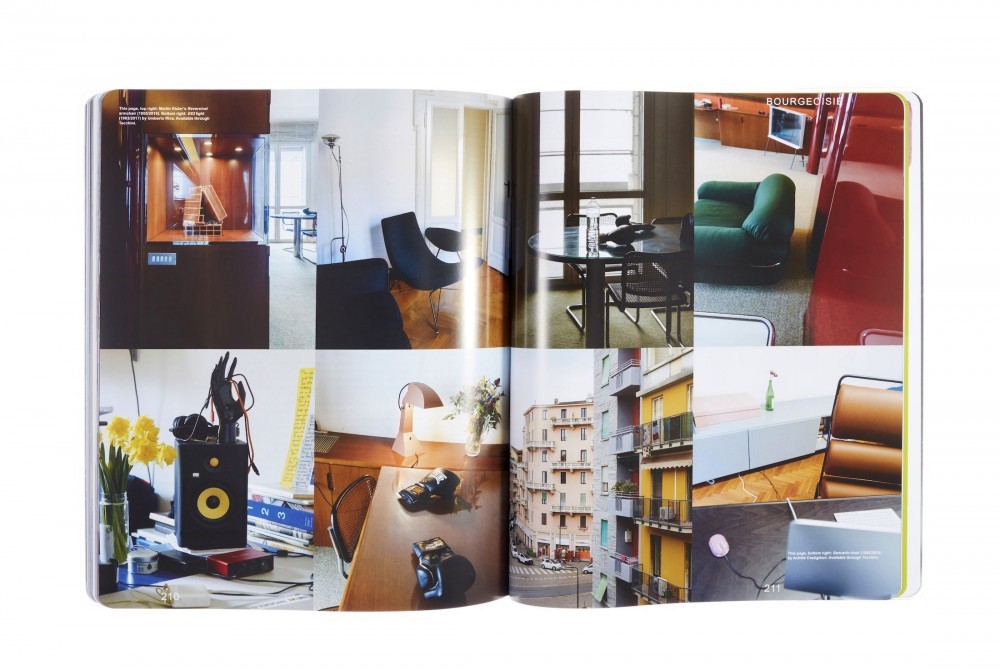

Left: Costela armchair (1952/2019) by Martin Eisler. Available through Tacchini.

The version of the bourgeoisie I have come to understand and be aware of is extremely localized within a 3+ kilometers radius with a fixed perimeter, both architectural and social. This version has nothing to do with money or assets, but with habit and comfort; an idea rather than a fact, a curse, and not a privilege, and, to use the most petite-bourgeois expression ever, something that’s in the details.

Exterior views of Milan apartments photographed by Piotr Niepsuj for PIN–UP.

Slow, easy, and extremely mundane, the everyday becomes a viable form of entertainment for a dazed jet-set of unrevolutionary characters, whose lives evolve in a predictable loophole of uneventful dichotomies — they spin in circles, gravitate at modest speed around an insignificant yet digestible orbit of habits.

Milan: a city that’s more understandable in terms of geometry than geography. The city’s circles — Roman fortifications evolved into feudal walls — expand from the central nucleus through a series of concentric rings that progressively divide the city center from its periphery. By design, Milan is a spiraling city, a blueprint for gated urbanism.

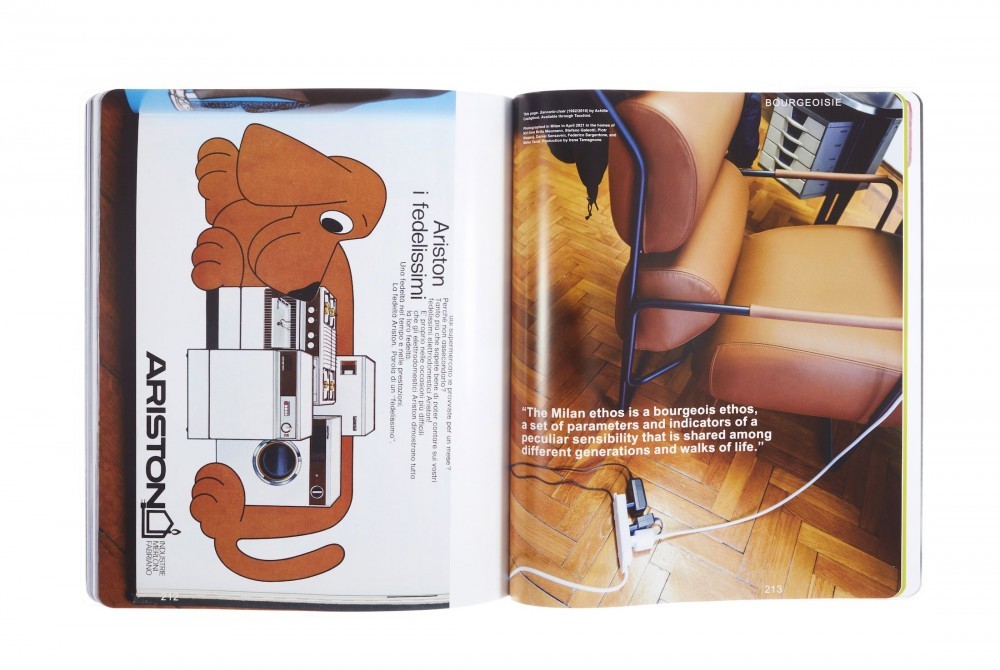

Through repetition, the historically preserved layout of the city has allowed the creation of a certain kind of spirit that infiltrates every aspect of the Milanese routine today. The Milan ethos is a bourgeois ethos, a set of parameters and indicators of a peculiar sensibility that is shared among different generations and walks of life.

As citizens of the same city, we are all guilty of the non-progressiveness we have caused. As members of the same generation, we are all guilty of the revolution we have never caused. Things don’t change, have never changed, and still, the bourgeois pattern of behavior drives us on autopilot.

Lina armchair (1955/2018) by Gianfranco Frattini. Available through Tacchini.

In her 1990 essay “About Piero & Me,” the late architect Nanda Vigo elaborated a sentimental account of her relationship with her partner, the artist Piero Manzoni, and his tragic death in 1963 at the age of 29. That piece, which reads like an intimate diary entry, is as much a love letter to the late artist, as it is to the city of Milan and its social dynamics. Manzoni died of a heart attack in his studio, allegedly having drunk himself to death after a night spent drifting around Milan’s Brera district with a posse of fellow companions, artists, and intellectuals. Manzoni and Vigo’s routine unfolded within a set of fixed coordinates that rarely extended outside of Brera, and involved a great deal of bar-hopping, late-night dinners, and fierce dissatisfaction with pretty much everything.

For a long time, I’ve been thinking of this essay for ages as the ultimate documentation of a bourgeois tragedy that unraveled with sorrow, yet grace, in an ironic twist of events — the man who was supposed to change everything, and subvert the intrinsic hierarchy in contemporary culture, lies dead in his studio, killed by the pathetic, well-educated, unglamorous, intellectually-charged, bourgeoise script he adapted his life to. Not even Manzoni himself managed to start that revolution.

Milan hasn’t changed much since then, and my peers and I have accepted the challenge of pretending to be rich. We are the Beat generation without a beat; we are the Situationists without situations; the Futurists with no future. We are a parody of industrialism and church-versus-state pedigree; we are living postcodes and nothing else. Milan is our muse — detached, frigid, unreadable — and so is its code: an instruction manual that’s not included in the box, a gossip column from a cheap Italian tabloid, a trope made of expensive furniture and ugly buildings. The truth is: no one gives a fuck about Milan. And to be honest, neither do I.

-

Photography by Piotr Niepsuj and text by Federico Sargentone in PIN–UP 30 Spring / Summer 2021. Spread photographed by Luke Libera Moore.

-

Photography by Piotr Niepsuj and text by Federico Sargentone in PIN–UP 30 Spring / Summer 2021. Spread photographed by Luke Libera Moore.

-

Photography by Piotr Niepsuj and text by Federico Sargentone in PIN–UP 30 Spring / Summer 2021. Spread photographed by Luke Libera Moore.

In music criticism, ambient is a genre that emphasizes tone and atmosphere over traditional musical structure or rhythm — a form of instrumental music that may lack composition, beat, or structured melody. In architecture, Angelo Lunati defines ambiente (ambiance) as the “space that surrounds a person or a thing,” with connotations of circularity due to the Greek prefix “amphi-” — as in amphitheater — which implicates a path that’s “all around.” In his book Ideas of Ambiente: History and Bourgeois Ethics in the Construction of Modern Milan, Lunati aims at defining Milan’s ambiente as the overarching quality in the development of the bourgeoisie metropolis.

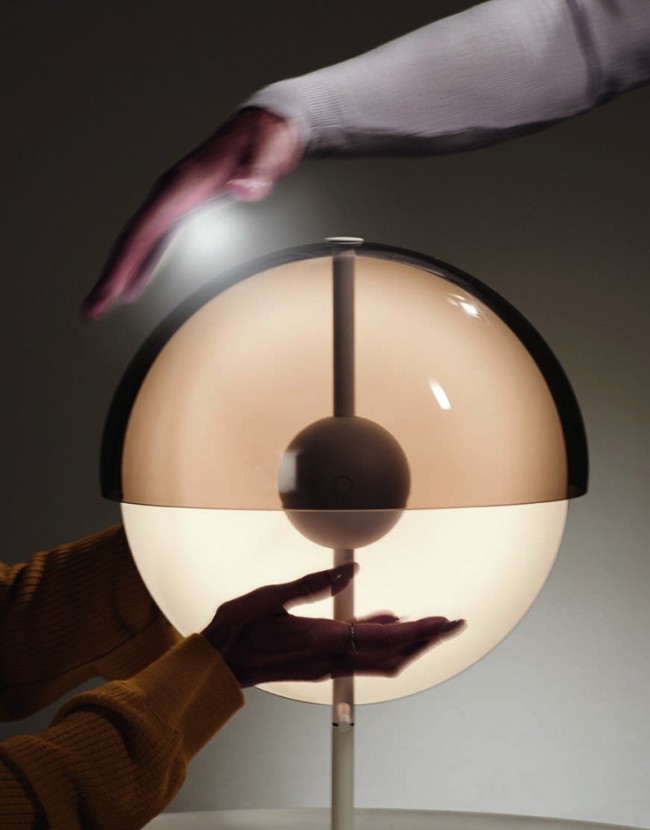

E63 light (1963/2017) by Umberto Riva. Available through Tacchini.

Milan is an ambient city whose concentric skeleton reinforced a class division that is mostly aesthetic rather than political, where the lack of ideology in architecture had contributed to the formation of the city’s distinctive character — an idea so deeply rooted within Milan’s social fabric that not even the 1970s avant-garde managed to destroy. I wonder if BBPR, Gae Aulenti, Aldo Rossi, or the Casabella crew would understand how their disruptive work exists today as the new bourgeoisie memento: poor rich kids and their posh thrift stores.

And yet, I have spent a great deal of time at my friends’ houses this year and, as in a temporal loop, I keep sitting on an always different, yet same, version of an Aulenti or Castiglioni armchair. This is clearly the aesthetic token we have been left with; the gold standard of Milanese life.

Right: Gianfranco Frattini’s Sesann armchair (1970/2015). Available through Tacchini.

Last year I became obsessed with a 1908 self-portrait by Umberto Boccioni, one of the very few the artist painted. In the work, the artist is portrayed on his balcony overlooking the Milanese countryside, where he’d moved to escape urban stress. One year later, in 1909, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti published his “Futurist Manifesto” and mailed it around Europe with a return address no further than one kilometer from Boccioni’s balcony. From Boccioni’s balcony, you can also see the building where I lived for three years.

The posh countryside had been counter-gentrified since Boccioni’s day, meaning that the rich have been kicked out of the neighborhood by the poor, who weren’t seeking refuge from urban stress as the painter did. That’s not a process that you get to see often in New York or London. We, the poor turned aesthetically bourgeois, keep this neighborhood for ourselves, but we still have to negotiate the upper-class aesthetics embedded in the area. Again, Lunati’s definition of ambiente as a complex network that transcends architecture to incorporate lifestyle, as an all-encompassing experiential dimension, provides context to the cyclical reinvention of bourgeois spaces.

Right: Sancarlo chair (1982/2010) by Achille Castiglioni. Available through Tacchini.

Milan: wonderful palace, mediocre lover.

This year I moved 500 meters away from Boccioni’s balcony. From mine, now, I can see the apartment of the photographer who shot this story, as well as the headquarters of the PR firm that facilitated it. In this insignificant portion of the universe, no manifesto has ever been written and I doubt it will be anytime soon because we don’t need one.

Manifestos — organized or informal declarations of intentions for purposes of divulgation and historicization — have heavily informed the research of critical design studio Experimental Jetset around radical art movements. In their recently published book Superstructures, the collective distills the revolutionary embodiment of historical avant-gardes within the Modernist city. Four models emerge from their analysis: the Constructivist city, the Situationist city, the Provotarian city, and the Post-Punk city. Although each of these models has specific characteristics derived from each of the movements, they all provide a reading of the cityscape as an extension of language. A Roland Barthes’s quote introduces the preface: “The city is a discourse, and this discourse is actually a language: the city speaks to its inhabitants, as we speak to our city…”

Sancarlo chair (1982/2010) by Achille Castiglioni. Available through Tacchini.

The language we speak here is the codified language of the bourgeoisie, as the ultimate conceptual detournement of status. We don’t speak it to our city but to ourselves. And if the discourse is actually a language, as per Barthes, our conversation with the city is overheard across coffee tables, politely intellectualized around late-70s sofa setups, repeated over and over incessantly through ideas and actions, embedded within a mode of behavior. Milan and its circles.

Text by Federico Sargentone

Photography by Piotr Niepsuj for PIN–UP

Creative Direction by Federico Sargentone for PIN–UP

Production by Irene Tamagnone

Photographed in Milan in April 2021 in the homes of Kiri-Una Brito Meumann, Stefano Galeotti, Piotr Niepsuj, Daniel Sansavini, Federico Sargentone, and Mirko Tanzi. Production by Irene Tamagnone